Interpreting History: the Importance and Limitations of Source Materials

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Critically analyze the validity and accuracy of historical source materials.

Looking forward

How do we know what we know about ancient art, its context, and its role within society in the world?

Modern scholars of ancient history are notoriously obsessed with evaluating their primary sources critically, and with good reason. Studying ancient history, especially in its earliest periods, is like putting together a puzzle, most of whose pieces are missing, and some pieces from another puzzle have also been added in for good measure. Ancient history requires careful consideration of a wide range of sources, which fall into two broad categories: literary sources (including both fiction and non-fiction), and material culture. The job of the historian, then, is to reconstruct the story of the ancient world using these very different sources.

As foundations of our research, these sources of information are typically classified into two main typological definitions — primary and secondary.

A primary source provides direct or firsthand evidence about an event, object, person or work of art. Characteristically, primary sources are contemporary to the events and people described and show minimal or no mediation between the document/artifact and its creator. As to the format, primary source materials can be written and non-written, the latter including sound, picture, and artifact.

A secondary source lacks the immediacy of a primary record. As materials produced sometime after an event happened, they contain information that has been interpreted, commented, analyzed or processed in such a way that it no longer conveys the freshness of the original.

The main difference between primary and secondary sources is how far away you are from the original event. In other words, a primary source is one that originated in the time/region that is under study, while a secondary source is one in which someone else has already analyzed and summarized the primary sources for you.

At this point in your academic career, you are probably very familiar with secondary sources. Secondary sources are important introductory materials to a variety of topics and include documents such as:

Textbooks

Magazine/journal articles

Histories

Commentaries

Encyclopedias

When you need a deeper understanding of a topic, primary sources serve as the most immediate materials and raw data. For scientists, primary research includes experiments and the raw data gleaned from that experimentation. For historians, primary sources are documents and/or physical objects that were written/created during the time period and location under study. These sources were present during a specific experience and offer an inside view of a particular event. Types of primary sources include:

Formal documentations: Diaries, speeches, manuscripts, letters, interviews, film footage, autobiographies, contracts, birth/death/marriage certificates, etc.

Literary sources: original works of art such as poetry, drama, novels, music, paintings, sculptures, architecture, etc.

Material culture: Furniture, clothing, bones, tools, etc.

While historians of the modern world rely on such archival sources as newspapers, magazines, and personal diaries and correspondence of individuals and groups, historians of the ancient world must use every available source to reconstruct the world in which their subject dwelled. Literary sources, such as epics, lyric poetry, and drama, may seem strange for historians to use, as they do not necessarily describe specific historical events. Yet, as in the case of other early civilizations, such sources are a crucial window into the culture and values of the people who produced them. For instance, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a key text for the study of early Mesopotamia.

- Kurt Raaflaub, “A Historian’s Deadache: How to Read ‘Homeric Society’?” in N. Fisher and H. Van wees eds., Archaic Greece: New Approaches and New Evidence (London: Duckworth: 1998). ↵

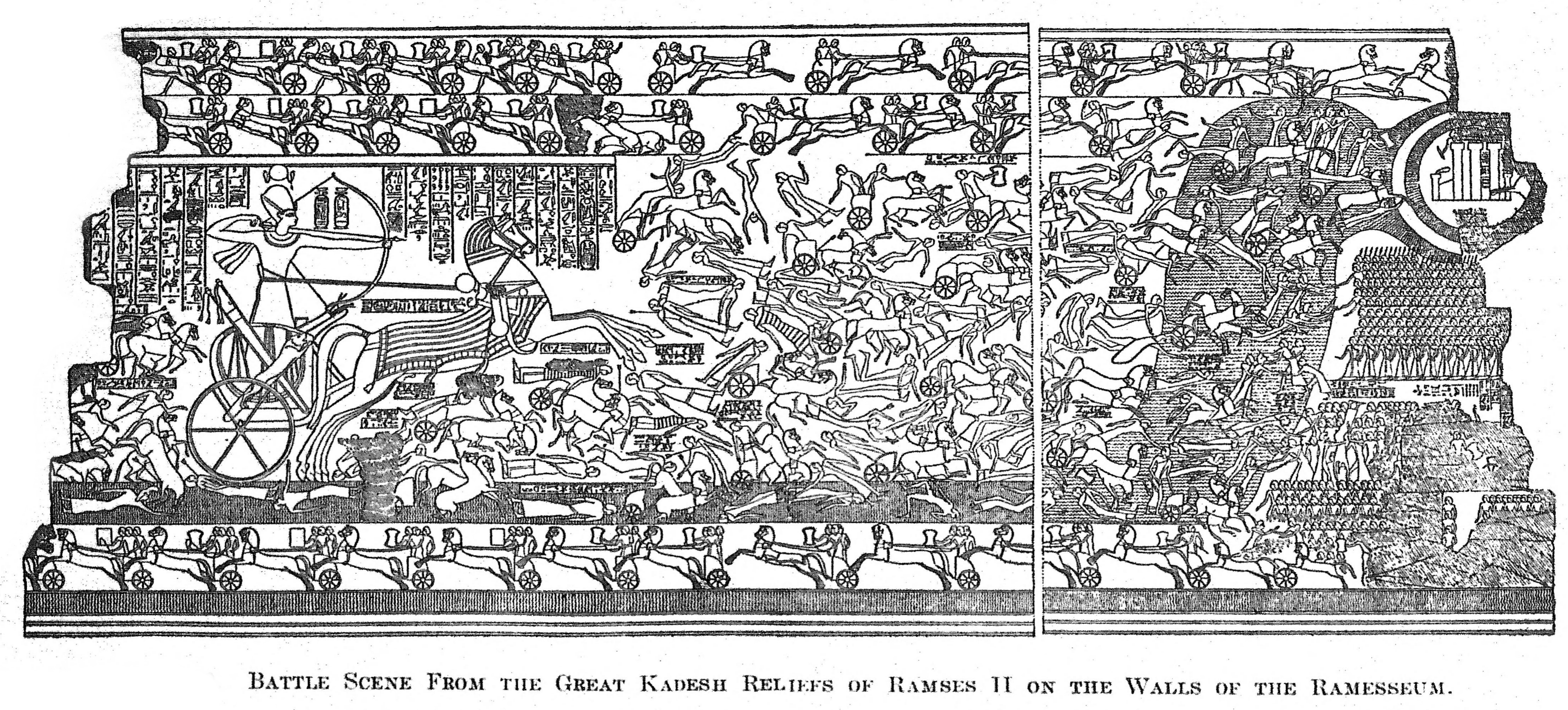

- Ramses II (the Great); King of Egypt. ↵

- the capital city of the Hittite Empire ↵

- Muwattalli (II); King of the Hittites ↵

- The Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty is the earliest known peace treaty and the only Ancient Near Eastern treaty for which the versions of both sides have survived. The treaty was inscribed on a silver tablet, of which three clay copies survived in the Hittite capital of Hattusa, now in Turkey. An Egyptian version survives on inscriptions at the Great Hypostyle Hall at the Temple of Karnak and at the Ramesseum. An enlarged replica of the agreement hangs on a wall at the headquarters of the United Nations, as the earliest international peace treaty known to historians. ↵