8 The Art of Christendom: The Middle Ages in Europe

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key works of art and differentiate between the arts of the Early Medieval, Romanesque, and Gothic periods.

- Characterize the art of early medieval Britain and Scandinavia.

- Trace the development of Gothic art and architecture in France from the twelfth through the fourteenth centuries.

The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages is generally dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 CE) to approximately 1000, which marks the beginning of the Romanesque period. The large-scale movements of the Migration Period[1], including various Germanic peoples, formed new kingdoms in what remained of the Western Roman Empire. In the West, most kingdoms incorporated the few extant Roman institutions. Monasteries were founded as campaigns to Christianize pagan Europe continued. The Franks, under the Carolingian dynasty, briefly established the Carolingian Empire during the later eighth and early ninth century. It covered much of Western Europe but later succumbed to the pressures of internal civil wars combined with external invasions—Vikings from the north, Hungarians from the east, and Saracens from the south.

Early medieval art in Europe grew out of the artistic heritage of the Roman Empire and the iconographic traditions of the early Christian church. These sources were mixed with the vigorous “Barbarian” artistic culture of Northern Europe to produce a remarkable artistic legacy. The history of medieval art can be seen as an ongoing interplay between the elements of classical, early Christian, and “barbarian” art. Apart from the formal aspects of classicism, there was a continuous tradition of realistic depiction that survived in Byzantine art of Eastern Europe throughout the period. In the West realistic presentation appears intermittently, combining and sometimes competing with new expressionist possibilities. These expressionistic styles developed both in Western Europe and in the Northern aesthetic of energetic decorative elements.

Hiberno-Saxon Art: The Sutton Hoo Burial

In the fifth century C.E., people from tribes called Angles, Saxons, and Jutes left their homelands in northern Europe to look for a new home. They knew that the Romans had recently left the green land of Britain unguarded, so they sailed across the channel in small wooden boats. The Britons did not give in without a fight, but after many years the invaders managed to overcome them, driving them to the west of the country. The Anglo-Saxons were to rule for over 500 years.

Anglo-Saxon metalwork consisted of Germanic-style jewelry and armor, which was commonly placed in burials. After the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity in the seventh century, the fusion of Germanic Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Early Christian techniques created the Hiberno-Saxon style (or Insular art) in the form of sculpted crosses and liturgical metalwork. Deriving from the Latin word for island (insula), Insular art is characterized by detailed geometric designs, interlace, and stylized animal decoration.

The most famous Anglo-Saxon treasures come from the Sutton Hoo burial site in Suffolk. Here mysterious grassy mounds covered a number of ancient graves. In one particular grave, belonging to an important Anglo-Saxon warrior, some astonishing objects were buried, but there is little in the grave to make it clear who was buried there.

In 1939 Mrs. Edith Pretty, a landowner at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, asked archaeologist Basil Brown to investigate the largest of several Anglo-Saxon burial mounds on her property. Inside, he made one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries of all time. Beneath the mound was the imprint of a 27-metre-long ship. At its center was a ruined burial chamber packed with treasures: Byzantine silverware, sumptuous gold jewelry, a lavish feasting set, and most famously, an ornate iron helmet.

When found, the magnificent helmet from the Anglo-Saxon grave at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, was in hundreds of pieces. The burial chamber had collapsed and reduced the helmet to a pile of fragments. Pieces of rusted iron were mixed up with pieces of tinned bronze, all so corroded as to be barely recognizable. By precisely locating the remaining fragments and assembling them as if in a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, conservators have reconstructed the helmet. A complete replica made by the Royal Armories shows how the original would have looked.

The helmet comprised an iron cap, neck guard, cheek pieces and face mask. Its form derives from Late Roman cavalry helmets. The helmet’s surfaces were covered with tinned copper alloy panels that gave it a bright, silvery appearance. Many of these panels were decorated with interlacing animal ornament and heroic scenes of warriors. One scene shows two men wearing horned headgear, holding swords and spears. The other shows a mounted warrior trampling a fallen enemy, who in turn stabs the horse. The rider carries a spear which is supported by a curious small figure, standing on the rump of his horse – perhaps a supernatural helper. Similar scenes were popular in the Germanic world at this time.

The facemask is the helmet’s most remarkable feature. It works as a visual puzzle, with two possible “solutions.” The first is of a human face, comprising eye-sockets, eyebrows, mustache, mouth and a nose with two small holes so that the wearer could breathe. The copper alloy eyebrows are inlaid with silver wire and tiny garnets. Each ends in a gilded boar’s head—a symbol of strength and courage appropriate for a warrior. The second “solution” is of a bird or dragon flying upwards. Its tail is formed by the mustache, its body by the nose, and its wings by the eyebrows. Its head extends from between the wings, and lays nose-to-nose with another animal head at the end of a low iron crest that runs over the helmet’s cap.

Anglo-Saxon metalwork initially used the Germanic Animal Style decoration that would be expected from recent immigrants, but gradually developed a distinctive Anglo-Saxon character. Decoration included cloisonné in gold and garnet for high-status pieces. Despite a considerable number of other finds, the discovery of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo transformed the history of Anglo-Saxon art, showing a level of sophistication and quality that was wholly unexpected at this date.

Sutton Hoo, an Anglo-Saxon treasure collected across Europe and Asia

Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance

On Christmas day in the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charles, king of the Franks, and raised him to the rank of emperor. The significance of this gesture must have been clear to all involved: it identified Charles as a new kind of Christian Caesar who should rule a Holy Roman Empire renewed and sanctioned by the Church. This act benefited the pope, for he was eager to gain the emperor’s protection and support for the Church, but it also fulfilled one of Charles’s most cherished aims: according to the scholar Einhard, who knew him well:

Throughout his whole reign, the wish that he had nearest to heart was to re-establish the ancient authority of the city of Rome under his care and by his influence.

This was no mean ambition, for when Charles became king of the Franks in 768, Rome had lost its imperial grandeur, and the vast domain it once had ruled was fragmented both politically and culturally. In the lands that now are Germany and France, a host of Germanic tribes competed for land and influence, observing various forms of Christianity and paganism. In Italy, the pope faced continual threats to his safety, and everywhere vestiges of Roman greatness inspired veneration for the past and pointed a sad contrast with the present.

The reign of Charles the Great, or Charlemagne, for a time reversed this situation. He enlarged his empire until it extended from Italy to the North Sea and from the English Channel to the Elbe River, and he worked to unify his people under the Church; he also emphasized the unity of church and state and fostered a cultural revival that raised educational standards, reformed the liturgy, and restored Latin to currency among men of letters. Historians use the word Carolingian, which comes from Carolus, the Latin version of the name Charles, to designate the distinctive imperial culture of Charlemagne’s age, which is sometimes called the Carolingian Renaissance[2]. This revival used Constantine’s Christian empire as its model, which flourished between 306 and 337. Constantine was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity and left behind an impressive legacy of military strength and artistic patronage.

There are many other ages in which artists sought to emulate Greco-Roman models, but the Carolingian revival has a uniquely political character and a unique dependence on the agenda of Charlemagne. Although he learned to read late and never mastered the ability to write, Charlemagne felt deep respect for the achievements of antiquity and recognized the prestige that classical learning conferred on his court.

Carolingian art survives in manuscripts, sculpture, architecture and other religious artifacts produced during the period 780-900. These artists worked exclusively for the emperor, members of his court, and the bishops and abbots associated with the court. Charlemagne commissioned the architect Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany. The chapel was consecrated in 805 and is known as the Palatine Chapel. This space served as the seat of Charlemagne’s power and still houses his throne today.

The Palatine Chapel at Aachen is the most well-known and best-preserved Carolingian building. It is also an excellent example of the classical revival style that characterized the architecture of Charlemagne’s reign. The exact dates of the chapel’s construction are unclear, but we do know that this palace chapel was dedicated to Christ and the Virgin Mary by Pope Leo III in a ceremony in 805, five years after Leo promoted Charlemagne from king to Holy Roman Emperor. The dedication took place about twenty years after Charlemagne moved the capital of the Frankish kingdom from Ravenna, in what is now Italy, to Aachen, in what is now Germany.

In the construction of his chapel, Charlemagne made several strategic choices that linked his building to the legacies of ancient Rome and the fourth-century emperor Constantine. The Emperor Constantine was important because he was the first Christian emperor of Rome. The location for the new building was selected because it was an historic Roman site with hot springs that were used for bathing. The materials used for the chapel also invoked Rome; among them were columns and marble stones that Pope Hadrian permitted Charlemagne to transfer from Rome and Ravenna to Aachen around the year 798. A relic of the cloak of St. Martin was installed in the church at its consecration—the choice of a fourth-century Roman soldier who had a vision of Jesus after sharing his cloak with a beggar was another way to reinforce the link of Charlemagne’s rule with Rome.

Carolingian architecture is characterized by its conscious attempts to emulate Roman classicism and Late Antique architecture. The Carolingians thus borrowed heavily from early Christian and Byzantine architectural styles, although they added their own innovations and aesthetic style. The result was a fusion of divergent cultural aesthetic qualities.

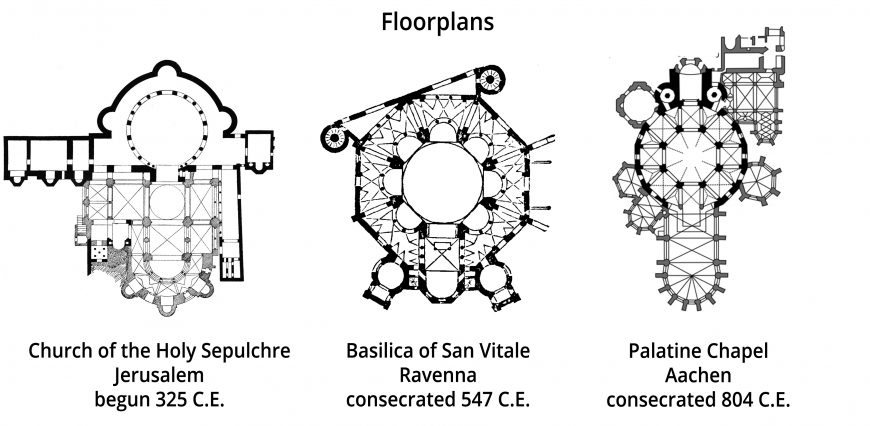

The chapel’s classical style also referenced its Roman imperial lineage, particularly in its imitation of two significant Christian buildings: the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem and San Vitale in Ravenna. The faithful believe that the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem contains the site of the crucifixion of Christ and the tomb from which he rose. The Holy Sepulcher’s building program was started in 325 C.E. by Constantine’s mother, Saint Helena, and completed in 335. The centralized plan and surrounding ambulatory and upper gallery is echoed in the plan of the Palatine Chapel. However, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem is composed of two main buildings—in addition to the rotunda that covers the tomb is a similar structure over the traditionally-accepted location of the crucifixion.

Because it didn’t receive extensive additions like the Holy Sepulcher, the San Vitale Chapel at Ravenna is probably the best comparison for what the Palatine Chapel would have looked like before its Gothic renovations. San Vitale is a small octagonal church, with a centralized plan and a two-story ambulatory.

The octagonal plan of the Palatine Chapel not only recalled that of its two most significant models, but also participated in the tradition of early Christian mausoleums and baptisteries, where the eight sides were understood to be symbolic of regeneration—referencing Christ’s resurrection eight days after Palm Sunday. Its original dome was also based on classical models and bore an apocalyptic mosaic program, consisting of the agnus dei, or Lamb of God (which is, symbolically, Jesus Christ), surrounded by the tetramorph (symbols of the four Gospel writers) and the twenty-four elders described in Revelation 4:4.

The Christian Tetramorph

A tetramorph is a symbolic arrangement of four differing elements, or the combination of four disparate elements into one unit.

In Christian iconography, it functions as the union of the symbols of the Four Evangelists, who appear in portraits derived from classical tradition and are frequently represented by the symbols which originate from the four “living creatures” that draw the throne-chariot of God, the Merkabah, in the vision in the Book of Ezekiel (Chapter 1) reflected in the Book of Revelation (4.6-9ff), though neither source links the creatures to the Evangelists.

When surrounding Christ, the figure of the man usually appears at top left – above Christ’s right hand, with the lion above Christ’s left arm. Underneath the man is the ox and underneath the lion is the eagle. This both reflects the medieval idea of the order of “nobility” of nature of the beasts (man, lion, ox, eagle) and the text of Ezekiel 1:10. From the thirteenth century their use began to decline, as a new conception of Christ in Majesty, showing the wounds of the Passion, came into use.

The meanings accruing to the symbols grew over centuries, with three set layers of meaning for the beasts: representing the Evangelists, the nature of Christ, and the virtues required of a Christian for salvation. These animals additionally may have originally been seen as representing the highest forms of the various types of animals: i.e., man, the king of creation as the image of the creator; the lion as the king of beasts of prey (meat-eating); the ox as the king of domesticated animals (grass-eating) and the eagle as the king of the birds.

Matthew: the angel

Matthew, the author of the first gospel account, which starts with Joseph’s genealogy from Abraham. He is symbolized by a winged man, or angel, which represents Jesus’ Incarnation, and so Christ’s human nature. This signifies that Christians should use their reason for salvation.

Mark: the lion

Mark, the author of the second gospel account, is symbolized by a winged lion – a figure of courage and monarchy. The lion also represents Jesus’ resurrection (because lions were believed to sleep with open eyes, a comparison with Christ in the tomb), and Christ as king. This signifies that Christians should be courageous on the path of salvation.

Luke: the bull

The author of the third gospel account (and the Acts of the Apostles), is symbolized by a winged ox or bull – a figure of sacrifice, service and strength.

Luke’s account begins with the duties of Zechariah in the temple; it represents Jesus’ sacrifice in His Passion and Crucifixion, as well as Christ being High priest (also Mary’s obedience). The ox signifies that Christians should be prepared to sacrifice themselves in following Christ.

John: the eagle

The author of the fourth gospel account is symbolized by an eagle – a figure of the sky, and believed by Christian scholars to be able to look straight into the sun. John’s gospel starts with an eternal overview of Jesus the Logos and goes on to describe many things with a “higher” Christology than the other three (synoptic) gospels; it represents Jesus’ Ascension, and Christ’s divine nature.

This symbolizes that Christians should look on eternity without flinching as they journey towards their goal of union with God.

The octagonal centralized plan of the Palatine Chapel is unique among Carolingian chapels; this may have been because, unlike a longitudinal plan which created a sense of processional direction toward the apse and altar, a centralized plan did not place special emphasis on the altar (and therefore may not have been as effective liturgically for the purpose of a chapel). That said, it does seem to have established an association of Charlemagne with Christ; some scholars believe that Charlemagne’s marble throne was originally located in the center of the octagon on the first floor, that is, directly below the image of the agnus dei, thereby creating a kind of visual link between the emperor and the Christ.

By presenting his capital at Aachen as a new Rome and himself as a new Constantine through the careful appropriation of late antique artwork and architecture, Charlemagne was not simply making a positive assertion about himself as ruler; he was also implicitly contrasting his reign with that of the Eastern Empire (the Byzantines), a negative stance that was also expressed around the same time in the Opus Caroli Regis contra Synodum (i.e., “The Work of King Charles against the Synod), a detailed response to the Second Council of Nicaea, written on his behalf by Theodulf of Orléans.

Figurative art from this period is easy to recognize. Unlike the flat, two-dimensional work of Early Christian and Early Byzantine artists, Carolingian artists sought to restore the third dimension. They used classical drawings as their models and tried to create more convincing illusions of space.

Lindau Gospels Cover

The Ottonian Empire

The revival of culture instituted by Charlemagne continued throughout the ninth century, but the empire that he had founded slowly disintegrated. Yet just as Charlemagne had aspired to Roman glory, later German princes yearned to restore his northern Christian empire. By the early tenth century, a ducal family from Saxony (in northern Germany) had mustered the power to claim royal standing, and in 936, Otto I, known as Otto the Great, was crowned king at Aachen; in 962, the pope invested him with the imperial title. Under the reigns of Otto I (r. 936–73), and of his son and grandson, Otto II (r. 973–83) and Otto III (r. 983–1002), the Holy Roman Empire was revived, albeit with a different geography[3] and a different character. The Ottonian emperors styled themselves the equals of the greatest rulers. They constructed a palace in Rome and spent long periods there near the pope, whose spiritual authority bolstered their claim to rule by God-given right. They also sought close ties with Byzantium, a power of much superior might and sophistication, and sealed a strategic alliance when the Byzantine princess Theophanu married Otto II in 972. In addition to political advantage, the Ottonians gained exposure to works of art that glorified other empires, and they in turn trumpeted their own aspirations by promoting the visual arts.

The Ottonian revival coincided with a period of growth and reform in the church, and monasteries produced much of the finest Ottonian art, including magnificent, illuminated manuscripts, churches and monastic buildings, and sumptuous luxury objects intended for church interiors and treasuries. Christian iconography predominated, but political imagery was often integrated with sacred scenes.

For a modern viewer, Ottonian art can be a little difficult to understand. The depictions of people and places don’t conform to a naturalistic style, and the symbolism is often obscure. When you look at Ottonian art, keep in mind that the aim for these artists was not to create something that looked “realistic,” but rather to convey abstract concepts, many of which are deeply philosophical in nature. The focus on symbolism can also be one of the most fascinating aspects of studying Ottonian art, since you can depend on each part of the compositions to mean something specific. The more time you spend on each composition, the more rewarding discoveries emerge.

The Ottonians were renowned for their metalwork, producing bejeweled book covers and massive bronze church doors with relief carvings depicting biblical scenes, a process so complex that it would not be repeated until the Renaissance. The most famous of these is the pair of church doors, the Bernward Doors, commissioned by Bishop Bernward of Hildesheim. Standing at 15 feet tall, they contain biblical scenes from the Gospels and the Book of Genesis in bronze relief, each cast in a single piece. These powerfully simple compositions convey their meanings by emphatic gestures, a hallmark of the Ottonian style.

The figures on the Bernward Doors feature a progressive style of relief, leaning out from the background instead of extending a uniform distance. A particularly apt example of this is the figure of Mary with the baby Jesus in the depiction of the Adoration of the Magi. While her lower body is still in low relief, her upper body and Christ project out further and her head and shoulders are cast in the round. This unusual style was used for artistic reasons, not because of technical limitations.

The Bernward Doors

Illustrated Books in the Early Middle Ages

Monks and monasteries had a deep effect on the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centers of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, and bases for missions and proselytizing. They were the main and sometimes only regional outposts of education and literacy. As literacy declined and printed material became available only to monks and nuns, art became the primary method of communicating narratives (usually of a Biblical nature) to the masses.

One of the most important art forms of the period was the illuminated manuscript, in which text is supplemented by ornamentation in the form of colored initials, decorative borders, and miniature illustrations, sometimes with the addition of gold and silver leaf. The earliest surviving substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period 400 to 600 CE and were initially produced in Italy and the Eastern Roman Empire. The significance of these works lies not only in their inherent art historical value, but also in the maintenance of literacy offered by non-illuminated texts as well. Had it not been for the monastic scribes of Late Antiquity who produced both illuminated and non-illuminated manuscripts, most literature of ancient Greece and Rome would have perished in Europe.

Early medieval illuminated manuscripts are the best examples of medieval painting, and indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of pre-Renaissance painting.

Hiberno-Saxon Manuscripts: The Lindisfarne Gospels

A medieval monk takes up a quill pen, fashioned from a goose feather, and dips it into a rich, black ink made from soot. Seated on a wooden chair in the scriptorium of Lindisfarne, an island off the coast of Northumberland in England, he stares hard at the words from a manuscript made in Italy.

This book is his exemplar, the codex from which he is to copy the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. For about the next six years, he will copy this Latin. He will illuminate the gospel text with a weave of fantastic images— snakes that twist themselves into knots or birds, their curvaceous and overlapping forms creating the illusion of a third dimension into which a viewer can lose him or herself in meditative contemplation.

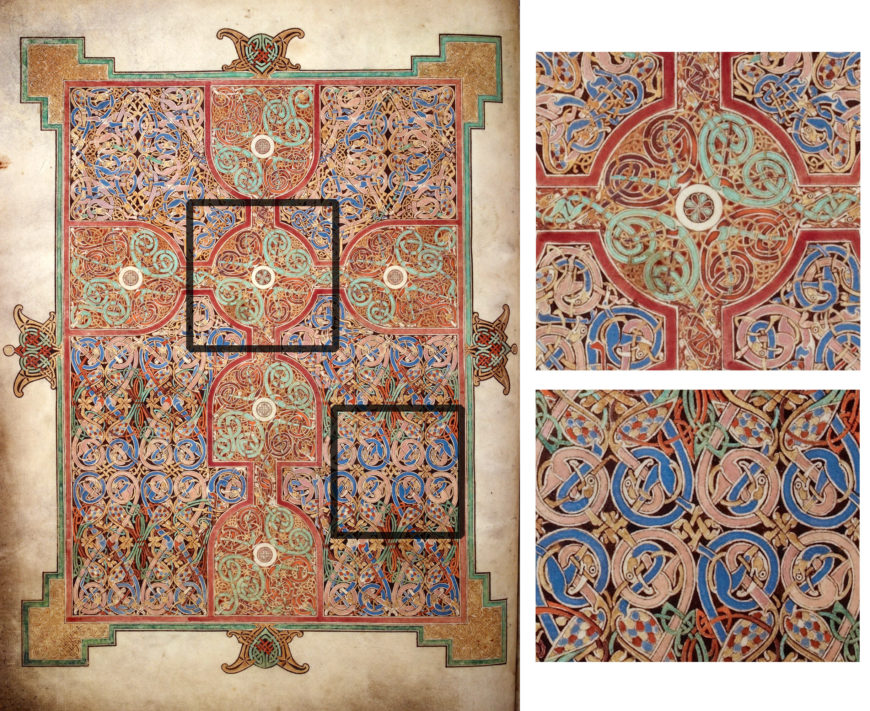

A Northumbrian monk, very likely the bishop Eadfrith, illuminated the codex in the early 8th century. Two-hundred and fifty-nine written and recorded leaves include full-page portraits of each evangelist; highly ornamental “cross-carpet” pages, each of which features a large cross set against a background of ordered and yet teeming ornamentation; and the Gospels themselves, each introduced by an historiated initial. The codex also includes sixteen pages of canon tables set in arcades. Here correlating passages from each evangelist are set side-by-side, enabling a reader to compare narrations.

Matthew’s cross-carpet page exemplifies Eadfrith’s exuberance and genius. A mesmerizing series of repetitive knots and spirals is dominated by a centrally located cross. Compositionally, Eadfrith stacked wine-glass shapes horizontally and vertically against his intricate weave of knots. On closer inspection many of these knots reveal themselves as snake-like creatures curling in and around tubular forms, mouths clamping down on their bodies. Chameleon-like, their bodies change colors: sapphire blue here, verdigris green there, and sandy gold in between. The sanctity of the cross, outlined in red with arms outstretched and pressing against the page edges, stabilizes the background’s gyrating activity and turns the repetitive energy into a meditative force.

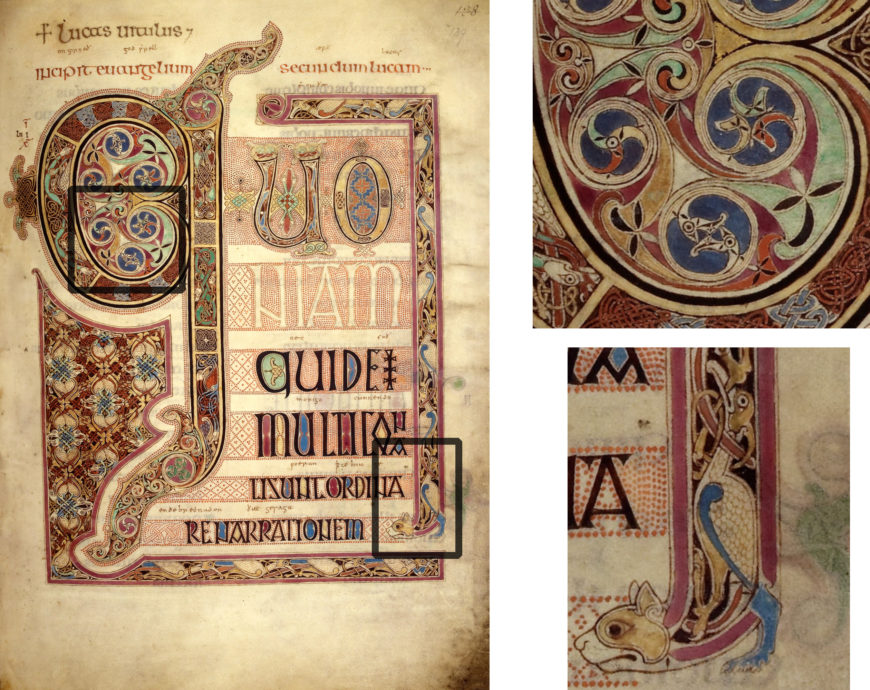

Likewise, Luke’s incipit page teems with animal life, spiraled forms, and swirling vortexes. In many cases Eadfrith’s characteristic knots reveal themselves as snakes that move stealthily along the confines of a letter’s boundaries. Blue pin-wheeled shapes rotate in repetitive circles, caught in the vortex of a large Q that forms Luke’s opening sentence—Quoniam quidem multi conati sunt ordinare narrationem. (“As many have taken it in hand to set forth in order.”)

Birds also abound. One knot enclosed in a tall rectangle on the far right unravels into a blue heron’s chest shaped like a large comma. Eadfrith repeats this shape vertically down the column, cleverly twisting the comma into a cat’s forepaw at the bottom. The feline, who has just consumed the eight birds that stretch vertically up from its head, presses off this appendage acrobatically to turn its body 90 degrees; it ends up staring at the words RENARRATIONEM (part of the phrase –re narrationem). Eadfrith also has added a host of tiny red dots that envelop words, except when they don’t—the letters “NIAM” of “quoniam” are composed of the vellum itself, the negative space now asserting itself as four letters.

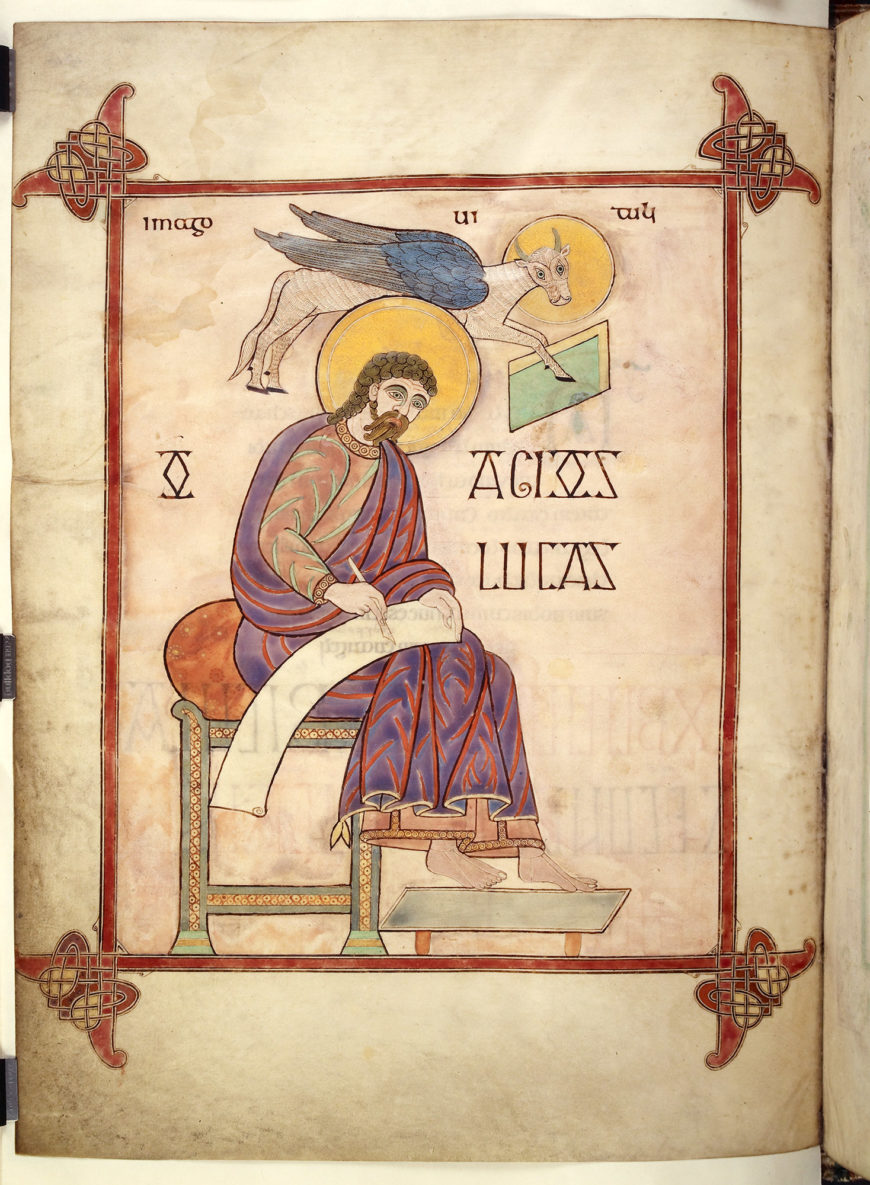

Luke’s incipit page is in marked contrast to his straightforward portrait page. Here Eadfrith seats the curly-haired, bearded evangelist on a red-cushioned stool against an unornamented background. Luke holds a quill in his right hand, poised to write words on a scroll unfurling from his lap. His feet hover above a tray supported by red legs. He wears a purple robe streaked with red, one that we can easily imagine on a late fourth or fifth century Roman philosopher. The gold halo behind Luke’s head indicates his divinity. Above his halo flies a blue-winged calf, its two eyes turned toward the viewer with its body in profile. The bovine clasps a green parallelogram between two forelegs, a reference to the Gospel. According to the historian Bede from the nearby monastery in Monkwearmouth (d. 735), this calf, or ox, symbolizes Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. Bede assigns symbols for the other three evangelists as well, which Eadfrith duly includes in their respective portraits: Matthew’s is a man, suggesting the human aspect of Christ; Mark’s the lion, symbolizing the triumphant and divine Christ of the Resurrection; and John’s the eagle, referring to Christ’s second coming.

All in all, the variety and splendor of the Lindisfarne Gospels are such that even in reproduction, its images astound. Artistic expression and inspired execution make this codex a high point of early medieval art.

The Lindisfarne Gospels

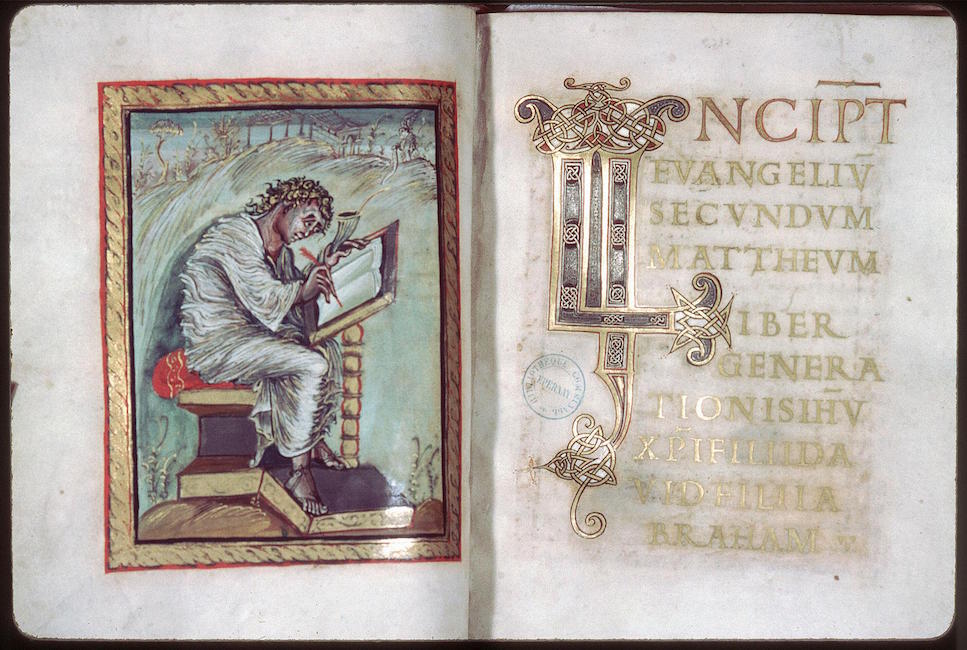

Carolingian Manuscripts: The Ebbo Gospels

Carolingian manuscripts are presumed to have been produced largely or entirely by clerics in a few workshops around the Carolingian Empire. Each of these workshops practiced its own style that developed based on the artists and influences of that particular location and time. The earliest workshop was the Court School of Charlemagne, then the Rheimsian workshop (which became the most influential of the Carolingian period), the Touronian style, the Drogo style, and the Court School of Charles II (the Bald).

In the early ninth century, Archbishop Ebbo of Rheims assembled clerical artists and transformed Carolingian art. The expressive animations of the Rheims School would have influence on northern medieval art for centuries to follow, far into the Romanesque period. One example was the Gospel Book of Ebbo (816–835), painted with swift, fresh, vibrant brush strokes that evoked an inspiration and energy unknown in classical Mediterranean forms. This emotionalism was new to Carolingian art. Figures in the Ebbo Gospels are represented in nervous, agitated poses. The illustration uses an energetic, streaky style with swift brush strokes.

While the author portraits in the Ebbo Gospels (images of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) are consistent with the elements of classical revival (e.g., modeling of figures to make them appear three-dimensional, gradation of the sky, the architecture and furnishings), the style in which the images of the Ebbo Gospels are executed is a notable departure. The brushwork of the author portraits can be described as energetic, expressionistic, even frenzied. The artist remains attentive to the use of highlighting and shadow to create three-dimensional forms, but does so with textured rather than smooth modeling, which creates an effect of movement.

This energy is conveyed not only in the brushwork, but also in the composition itself. In the Ebbo Gospels, Matthew is hunched over as if frantically writing on his (still blank) codex. The lines are dynamic and lack a sense of equilibrium. For instance, Matthew’s right foot in particular is positioned on the steep, almost vertical, angle of his footrest. Furthermore, the book stand is tipped at such a drastic angle that it seems his book will slide right into the viewer’s lap. The energy is also expressed in Matthew’s face, which is drawn up in a furrowed brow. Matthew appears to be in anguish over his writing, which is directed by his evangelist symbol, the winged man, who instructs him from the upper right-hand corner of the image.

Saint Matthew from the Ebbo Gospels

Ottonian Manuscripts: Gospel Book of Otto III

Ottonian monasteries produced some of the most magnificent medieval illuminated manuscripts, working with the best equipment and talent under the direct sponsorship of emperors, bishops, and other wealthy patrons. The manuscripts produced by Ottonian scriptoria provide invaluable documentation of contemporary, religious, and political customs as well as the stylistic preferences of the period. The most richly illuminated manuscripts were used for display and were mostly liturgical books, including psalters, gospel books, and large, complete Bibles. These lavish manuscripts sometimes include a dedication portrait commemorating the book’s creation in which the patron is usually depicted presenting the book to the chosen saint. Colored initials, borders, and marginalia also contain miniature portraits and other decorative emblems and motifs.

The double page opening of the ruler portrait of Otto III (f.24) and the accompanying image of provinces bringing tribute (f.23v) is taken from the Gospels of Otto III. One of the most magnificent manuscripts to have come down to us from the early medieval period, it is thought to have been made about the year 1000 at the Benedictine monastery of Reichenau on Lake Constance where Austria, Switzerland and Germany converge.

The pages of the Gospels of Otto III manuscript measure 334 by 242 millimeters and are made of parchment. The script is written in ink, with gold initials, and the manuscript is extensively illustrated with portraits of the four evangelists (the authors of the four gospels), and scenes from the life of Christ as well as the ruler portrait. The front cover is decorated with precious jewels and inset with a Byzantine ivory representing the dormition or death of the Virgin Mary. The double-page is near the beginning of the manuscript before the gospel texts.

Otto III was the Holy Roman Emperor and nominally ruled over territories corresponding to modern day Germany, France and northern Italy. The pendant image depicts four personifications of the territories over which Otto ruled and who are shown bringing him tribute. They are identified as: Sclavinia (Slavic east), Germania (roughly Germany), Gallia (roughly France), and Roma (Rome). There is a parallel between this scene and that of the adoration of the three magi bringing gifts to the infant Christ (represented on f.29 of the manuscript), which underlines the quasi-divine nature of the Emperor.

On the right side of the double page, emperor Otto III is shown seated frontally, crowned, and holding a golden orb and a scepter surmounted by an eagle. Otto III looks out at us with hypnotic eyes, dressed in green and the imperial purple, and is flanked on either side by members of his court: on the right by those who fight (two members of the nobility who carry a sword, a lance and shield) and, on the left, by those who pray (two members of the clergy who hold books).

This is not a portrait in the conventional sense of a likeness and gives us very little idea of what Otto III must have looked like. Otto III is represented out of proportion with the much smaller figures that flank him—indicating his status. The opening pages probably represent an ideal of Otto III’s rule rather than the reality of his situation as his rule was fraught with division. The style of the opening looks back to late antique illusionism but has an extraordinary flatness to it as if the scene has been pressed between two panes of glass.

The Romanesque Period

Y2K. The Rapture. 2012. For over a decade, speculation about the end of the world has run rampant—all in conjunction with the arrival of the new millennium. The same was true for our religious European counterparts who, prior to the year 1000, believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent, and the end was nigh. When the apocalypse failed to materialize in 1000, it was decided that the correct year must be 1033, a thousand years from the death of Jesus Christ, but then that year also passed without any cataclysmic event.

Just how extreme the millennial panic was, remains debated. It is certain that from the year 950 onward there was a significant increase in building activity, particularly of religious structures. There were many reasons for this construction boom beside millennial panic, and the building of monumental religious structures continued even as fears of the immediate end of time faded. As Europe grew steadily more prosperous during this period, art of the highest quality was no longer confined to the royal court and a small circle of monasteries as in the Carolingian and Ottonian periods.

The term “Romanesque,” meaning in the manner of the Romans, was first coined in the early nineteenth century. Today it is used to refer to the period of European art from the second half of the eleventh century throughout the twelfth (with the exception of the region around Paris where the Gothic style emerged in the mid-12th century).

Romanesque Architecture

Romanesque architecture was the first distinctive style to spread across Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Combining features of Roman and Byzantine buildings along with other local traditions, Romanesque architecture is distinguished by massive quality, thick walls, round arches, sturdy piers, groin vaults, large towers, and decorative arcades. Each building has clearly defined forms and a symmetrical plan, resulting in a much simpler appearance than the Gothic buildings that would follow.

Although architectural styles varied from place to place, building to building, there are some basic features that were fairly universal in monumental churches built in the Middle Ages, and the prototype for that type of building was the Roman basilica.

In ancient Rome, the basilica was created as a place for tribunals and other types of business. The building was rectangular in shape, with the long, central portion of the hall made up of the nave. Here the interior reached its fullest height. The nave was flanked on either side by a colonnade (a row of columns) that delineated the side aisles, which were of a lower height than the nave. Because these side aisles were lower, the roof over this section was below the roofline of the nave, allowing for windows near the ceiling of the nave. This band of windows was called the clerestory. At the far end of the nave, away from the main door, was a semi-circular extension, usually with a half-dome roof. This area was the apse and is where the magistrate or other senior officials would hold court.

Because this plan allowed for many people to circulate within a large, and awesome, space, the general plan became an obvious choice for early Christian buildings. The religious rituals, masses, and pilgrimages that became commonplace by the Middle Ages were very different from today’s services, and to understand the architecture it is necessary to understand how the buildings were used and the components that made up these massive edifices.

Although medieval churches are usually oriented with the altar on the east end, they all vary slightly. When a new church was to be built, the patron saint was selected, and the altar location laid out. On the saint’s day, a line would be surveyed from the position of the rising sun through the altar site and extending in a westerly direction. This was the orientation of the new building.

The entrance foyer at the west end is called the narthex, but this is not found in all medieval churches. Daily access may be through a door on the north or south side. The largest, central, western door may have been reserved for ceremonial purposes.

The nave was used for the procession of the clergy to the altar. The main altar was basically in the position of the apse in the ancient Roman basilica, although in some designs it is further forward. The area around the altar—the choir or chancel—was reserved for the clergy or monks, who performed services throughout the day.

An aisle often surrounds the apse, running behind the altar. Called the ambulatory, this aisle accessed additional small chapels, called radiating chapels. The cathedrals and former monastery churches are much larger than needed for the local population. They expected and received numerous pilgrims who came to various shrines and altars within the church where they might pray to a supposed piece of the true cross, or a bone of a martyr, or the tomb of a king. The pilgrims entered the church and found their way to the chapel or altar of their desire—therefore, the side aisles made an efficient path for pilgrims to come and go without disrupting the daily services.

Pilgrimage Churches and the Cult of the Relic

The transmission of ideas was facilitated by increased travel along the pilgrimage routes to shrines, such as Santiago de Compostela in Spain, or as a consequence of the crusades, which passed through the territories of the Byzantine empire. Pilgrimage churches were constructed with some special features to make them particularly accessible to visitors. The goal was to get large numbers of people to the relics and out again without disturbing the Mass in the center of the church.

The cult of relic was at its peak during the Romanesque period (c. 1000 – 1200). Relics are religious objects generally connected to a saint, or some other venerated person. A relic might be a body part, a saint’s finger, a cloth worn by the Virgin Mary, or a piece of the True Cross.

Relics are often housed in a protective container called a reliquary, which were often quite opulent and can be encrusted with precious metals and gemstones given by the faithful. An example is the Reliquary of Saint Foy, which is said to hold a piece of the child martyr’s skull. A large pilgrimage church might be home to one major relic, and dozens of lesser-known relics. Because of their sacred and economic value, every church wanted an important relic and a black market boomed with fake and stolen goods.

At the entrance of these pilgrimage churches, a large portal that could accommodate the pious throngs was a prerequisite. Generally, these portals would also have an elaborate sculptural program, often portraying the Second Coming—a good way to remind the weary pilgrim why they made the trip!

The church of Ste. Pierre (St. Peter) in Moissac, France, dating from 1115-30, has one of the most impressive and elaborate Romanesque portals of the twelfth century. Carved images occupy the walls of the extended porch leading to the door, the door itself, and even the space over the door. The church of Ste. Pierre was on one of the pilgrimage roads through France that led to Santiago de Campostela, in Spain and was a popular stop for those making the long and arduous journey to Spain.

In order to understand what is depicted on the main areas surrounding the portal that leads into the church, let’s break it down into its constituent parts. The term portal refers to a doorway or entry into a building, and Romanesque portals have distinct architectural elements which were oftentimes carved with a variety of ornament and subject matter.

In the case of Ste. Pierre, the portal is divided in half vertically by the trumeau, which is decorated on three of its four sides. On the front, the viewer is faced with three pairs of intertwined lions and lionesses who are there to symbolically guard the entry into the sacred space of the church. Such symbolism comes from Early Christian imagery where the doors to Christ’s tomb are often shown with lion’s heads on them. On the east side of the trumeau is a representation of the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah (some scholars suggest it is Isaiah), who holds a scroll in his hands. On the west side is a figure identified as St. Paul, from the New Testament.

The placement of these two figures on the sides of the trumeau was no doubt deliberate as they face two other figures on the door jambs (the outer walls of the portal where the doors are attached). Across from St. Paul is a representation of St. Peter, also a New Testament saint (and the namesake of the church), and across from Jeremiah, is the Old Testament prophet Isaiah. The pairing of Old and New Testament figures was common during this period as a means of suggesting the fulfillment of Mosaic law[4] in the new Christian law under Christ.

The trumeau has more than just a decorative function though as it also supports the horizontal beam of stone above called the lintel. The lintel is decorated with ten rosettes that are bound together by a carved rope and have a repeated floral pattern at both the upper and lower spaces between each rosette.

Just above the lintel is the lunette-shaped (semi-circular) tympanum, which has the majority of the sculpted decoration (and this is true in most Romanesque and Gothic portals). In this case, the tympanum is surrounded by three decorative archivolts (arches), which have various foliate patterns carved into the individual blocks of stone, known as the voussoirs, which make them up.

During the Romanesque and Gothic periods, there were two subjects which were popular for tympanum decoration. One was the subject known as the Maiestas Domini (Christ in Majesty), and at Moissac we are presented with a very literal depiction of a passage from the Book of Revelation (4:2–7), which reads:

And immediately I was in the Spirit, and behold a throne was set in heaven, and one sat on the throne…And round the throne were four and twenty seats; and upon the seats I saw four and twenty elders sitting, clothed in white raiment; and they had on their heads crowns of gold…And before the throne there was a sea of glass like unto a crystal; and in the midst of the throne, and round about the throne, were four beasts…And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast like a calf, and third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle.

The moment described in this passage is not a narrative in the sense that the Last Judgment is, but it is rather a more esoteric concept of the Second Coming of Christ and the End of Time.

The other commonly depicted scene was the Last Judgment, when Christ sits as judge over those who will be divided into the Saved and the Damned. As the road weary pilgrims would have approached the portal of the church, they were met with spectacular imagery that warned against sin and reminded them of Christ’s sacrifice and his final coming.

Last Judgement Tympanum, Cathedral of St. Lazare, Autun

Romanesque Sculpture: Mary as the Throne of Wisdom

The image of the Virgin and Christ Child was ubiquitous in medieval art. Architectural and portable sculpture, altarpieces, stained glass windows, and other art works featured the Mother of God with her infant son. The Virgin Mary was regarded as the Queen of Heaven, the great intercessor between her Son and the helpless earthly souls who looked to her in time of need. The familiar Gothic depiction of an approachable Virgin as a beautiful young queen, standing in an S curve and delicately balancing the small Christ Child on her hip, was preceded by the more sober, rigid, and hieratic Romanesque depiction of a seated Virgin holding the Christ Child on her lap, a type referred to as a “Throne of Wisdom[5]”.

Referred to as “Majesties” in contemporary texts, the sculptures are simple compositions in which the Virgin Mary sits on a throne with the Christ Child sitting on her lap. Strictly frontal with expressionless faces, both figures wear simple tunics, the ripples of which fall in perfect, repetitive patterns, resulting in a very stiff and symmetrical quality. In Christian iconography, sedes sapientiae (“The Throne of Wisdom”) is an icon of the Mother of God in majesty. A number of these sculptures have come down to us from the 12th century and are true sculptures in the round, made of wood, and usually measuring 3-4 feet in height. They were designed for mobility—carried in the many processions of the Middle Ages in celebration of feast days (a practice which continues in some parts of Europe to this day). Believed to be a manifestation of the Virgin’s presence and authority, the sculpture was paraded around during times of war, famine, disease, or to simply collect money for the church. Like other portable sculpture of the Middle Ages, they were an essential part of communal religious life.

A good example of a “Throne of Wisdom” sculpture which still retains some of its original color is found at the Cloisters Museum, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The sculpture is made from several pieces of walnut doweled together. Originally, the Virgin wore a red robe covered by a dark blue mantle which was decorated with tin leaf to simulate gold. Christ’s tunic was originally a dark green with red lining, covered by a red overgarment known as a himation. This too was originally decorated with tin leaf.

The sculpture puts into visual form the typological tradition of comparing Mary to the Throne of Solomon (typology refers to the idea that events and individuals in the Old Testament prefigured those in the New Testament). King Solomon’s famous throne is described in the Book of Kings of the Old Testament as a throne of ivory covered in gold. Christ, like his ancestor King Solomon, embodies wisdom and justice. Thus, Mary is a Sedes Sapientiae or Throne of Wisdom—the Mother of God, enthroned herself, who serves as a throne for the son of God turned into human flesh. The Christ Child on her lap represents divine wisdom incarnate, whose wisdom is communicated through his adult features, making him look like a miniature man. The open bible he holds is also a representation of the divine wisdom he embodies.

To the medieval mind, the Throne of Wisdom statues were earthly manifestations of both the presence and the authority of the Virgin Mary. They were seen as a way to communicate with the heavenly court—relaying people’s prayers and interceding on their behalf. In fact, the statues were not thought to have been made by sculptors in workshops, but to be miraculous in origin. Stories range from one being discovered by woodcutters enclosed in a tree to one arriving on a ship without sailors or oars and enveloped in a bright light. They were also said to be immune to fire as a number of accounts attest of statues surviving church fires without even being scorched.

The Throne of Wisdom sculptures also functioned within the broader context of the growing cult of relics in medieval Europe. There is ample evidence suggesting that the Throne of Wisdom sculptures were occasionally used as reliquaries. Our example from the Cloisters has a small circular cavity on the Virgin’s left shoulder and x-rays confirm a relic contained within. The relic may not necessarily be associated with the Virgin Mary (parts of her clothing or veil, strands of her hair, and drops of her milk were frequently cited relics) but could be fragments of another holy individual. Whatever the relic, its inclusion would have made the Virgin’s perceived intercessory power that much more effective.

Virgin from Ger

Gothic Europe

Forget the association of the word “Gothic” to dark, haunted houses, Wuthering Heights, or ghostly pale people wearing black nail polish and ripped fishnets. The original Gothic style was actually developed to bring sunshine into people’s lives, and especially into their churches. To get past the accrued definitions of the centuries, it’s best to go back to the very start of the word Gothic, and to the style that bears the name.

The Goths were a so-called barbaric tribe who held power in various regions of Europe, between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire (so, from roughly the fifth to the eighth century). They were not renowned for great achievements in architecture. After the fall of the Roman Empire, people fled cities as they were no longer safe. The Romanesque era saw many people living in the countryside of France while cities remained largely abandoned. During this time period, the French monarchy was weak and feudal landowners exerted a large amount of regional power. In the 12th century, the French royalty strengthened their power, their titles, and their landholdings, which led to more centralized government. Additionally, due to advancements in agriculture, population and trade increased. These changes brought people back to the cities, which is where we find the most expressive medium for the Gothic style—cathedrals.

The style represented giant steps away from the previous, relatively basic building systems that had prevailed. The Gothic grew out of the Romanesque architectural style, when both prosperity and relative peace allowed for several centuries of cultural development and great building schemes. From roughly 1000 to 1400, several significant cathedrals and churches were built, particularly in Britain and France, offering architects and masons a chance to work out ever more complex and daring designs.

As with many art historical terms, “Gothic” came to be applied to a certain architectural style after the fact. After the great flowering of Gothic style, tastes again shifted back to the neat, straight lines and rational geometry of the Classical era. It was in the Renaissance that the name “Gothic” came to be applied to this medieval style that seemed vulgar to Renaissance sensibilities. It is still the term we use today[6], though hopefully without the implied insult, which negates the amazing leaps of imagination and engineering that were required to build such edifices.

Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the ambulatory of St. Denis

Gothic architecture is unique in that we can pinpoint the exact place, the exact moment, and the exact person who developed it. Around 1137, Abbot Suger began re-building the Abbey Church of St. Denis. In his re-designs, which he wrote about extensively, we can see elements of what would become Gothic architecture, including the use of symmetry in design and ratios.

The Abbey Church of Saint Denis, also known as the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Denis, is a large medieval abbey church in the commune of Saint Denis, now a northern suburb of Paris. This site originated as a Gallo-Roman cemetery in late Roman times. Around 475 CE, St. Genevieve established a church at this site. In the 7th century, this structure was replaced by a much grander construction, on the orders of Dagobert I, King of the Franks.

The Basilica of Saint Denis is an architectural landmark, the first major structure of which a substantial part was designed and built in the Gothic style. Both stylistically and structurally, it heralded the change from Romanesque architecture to Gothic architecture.

Ratios became essential to French Gothic cathedrals because they expressed the perfection of the universe created by God. This is where we also see stained glass emerge in Gothic architecture. Abbot Suger adopted the idea that light equates to God. He wrote that he placed pictures in the glass to replace wall paintings and talked about them as educational devices. The windows were instructional in theology during the Gothic era, and the light itself was a metaphor for the presence of God.

Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the ambulatory at St. Denis

Gothic Architecture in France and England

The Gothic cathedral represented the universe in microcosm, and each architectural concept, including the height and perfect ratios of the structure, were intended to convey a theological message: the great glory of God and his creation of a perfect universe. The building becomes a microcosm in two ways. First, the mathematical and geometrical nature of the construction is an image of the orderly universe, in which an underlying rationality and logic can be perceived. Second, the statues, sculptural decoration, stained glass, and murals incorporate the essence of creation in depictions of events from the Old and New Testaments.

Most Gothic churches have the Latin cross (or “cruciform”) plan, with a long nave making the body of the church. This nave is flanked on either side by aisles, a transverse arm called the transept, and, beyond it, an extension referred to as the choir.

One of the defining characteristics of Gothic architecture is the pointed or ogival arch. Arches of this type were used in the Near East in pre-Islamic as well as Islamic architecture before they were structurally employed in Gothic architecture. They are thought to have been the inspiration for their use in France at the Autun Cathedral, which is otherwise stylistically Romanesque.

Rather than having massive, drum-like columns as in the Romanesque churches, the new columns could be more slender. This slimness was repeated in the upper levels of the nave, so that the gallery and clerestory would not seem to overpower the lower arcade. In fact, the column basically continued all the way to the roof and became part of the vault.

The Gothic vault, unlike the semi-circular vault of Roman and Romanesque buildings, can be used to roof rectangular and irregularly shaped plans such as trapezoids. This enabled architects to raise vaults much higher than was possible in Romanesque architecture. While the use of the pointed arch gave a greater flexibility to architectural form, it also gave Gothic architecture a very different and more vertical visual characteristic than Romanesque architecture.

In Gothic architecture the pointed arch is used in every location where a vaulted shape is called for, both structurally and decoratively. Gothic openings such as doorways, windows, arcades, and galleries have pointed arches. Rows of pointed arches upon delicate shafts form a typical wall decoration known as a blind arcade. Niches with pointed arches that contain statuary are a major external feature. The pointed arch lent itself to elaborate intersecting shapes, which developed complex Gothic tracery within window spaces and formed the structural support of the large windows that are characteristic of the style.

The façade of a large church or cathedral, often referred to as the West Front, is generally designed to create a powerful impression on the approaching worshiper. In the arch of the door (the tympanum) is often a significant sculpture representing scenes from Christian Theology, most frequently Christ in Majesty and Judgment Day. If there is a central door jamb or a tremeau, then it frequently bears a statue of the Madonna and Child.

The West Front of a French cathedral, along with many English, Spanish, and German cathedrals, generally has two towers, which, particularly in France, express an enormous diversity of form and decoration. A characteristic of French Gothic church architecture is its height, both absolute and in proportion to its width, the verticality suggests an aspiration to Heaven. As the Gothic Age progressed in France, the different towns and cities may have been in competition with one another to create the tallest Cathedral. Architects also closely guarded the ratios they used in their architectural plans.

Another one of the most distinctive characteristics of Gothic architecture is the expansive area of windows and the large size of the many individual windows. The increase in the use of large windows during the Gothic period is directly related to the use of the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, and the flying buttress. All of these architectural features absorbed the weight of the structure, which had rested on the walls in Romanesque architecture. Since the walls had less weight to support, thanks to these innovations, architects were able to pierce the walls of the structures with windows without risking the structural soundness of the cathedral.

Chartres Cathedral, Notre-Dame, and Sainte-Chapelle

While the Gothic style was developed in Northern France, it spread throughout Europe where different regional styles were adopted. While French Gothic Cathedrals were built to be increasingly tall, English Gothic Cathedrals tended to emphasize the length of the building rather than the height.

Many of the largest and finest works of English architecture, notably the medieval cathedrals of England, are largely built in the Gothic style. The earliest large-scale applications of Gothic architecture in England are at Canterbury Cathedral and Westminster Abbey. Castles, palaces, great houses, universities, parish churches, and many smaller unpretentious secular buildings, including almshouses and trade halls, were also built in this style.

The Early English Gothic period lasted from the late 12th century until midway through the 13th century, according to most modern scholars. By 1175, the Gothic style had been firmly established in England with the completion of the Choir at Canterbury Cathedral by William of Sens.

The most significant characteristic development of the Early English period was the pointed arch known as the lancet. Compared with the rounded Romanesque style, the pointed arch of the Early English Gothic is aesthetically more elegant and is more efficient at distributing the weight of stonework, making it possible to span higher and wider gaps using narrower columns. It also allows for much greater variation in proportions.

Using the pointed arch, walls could become less massive and window openings could be larger and grouped more closely together, so architects could achieve more open, airy, and graceful buildings. At its purest, the style was simple and austere, emphasizing the height of the building, as if aspiring heavenward. In the late 12th century, the Early English Gothic style superseded the Romanesque style, and during the late 13th century it developed into the Decorated Gothic style, which lasted until the mid-14th century. Decorated architecture is characterized by its window tracery, which are elaborate patterns that fill the top portions of windows. The tracery style was geometric at first and flowing in the later period during the 14th century. Vaulting also became more elaborate, with the use of increasing numbers of ribs, initially for structural and later for aesthetic reasons.

Salisbury Cathedral

The Perpendicular Gothic period is the third historical division of English Gothic architecture and is characterized by an emphasis on vertical lines. The Perpendicular style began under the royal architects William Ramsey and John Sponlee and lasted into the mid-16th century.

The Perpendicular style grew out of the shadow of the Black Death, a disease that killed approximately half of England’s population in 18 months between June 1348 and December 1349 and returned in 1361–62 to kill another fifth of the population. This epidemic dramatically impacted every aspect of society, including arts and culture, and designers moved away from the flamboyance and jubilation present in the Decorated style. Architects were also responding to labor shortages resulting from the plague, and therefore relied on less elaborate designs.

Perpendicular linearity is particularly obvious in the design of windows, which became immense, allowing greater scope for stained glass craftsmen. Some of the finest features of this period are the magnificent timber roofs: hammerbeam roofs, such as those of Westminster Hall (1395), Christ Church Hall, Oxford, and Crosby Hall, appeared for the first time. Gothic architecture continued to flourish in England for 100 years after the precepts of Renaissance architecture were formalized in Florence in the early 15th century.

Gloucester Cathedral

Gothic Sculpture

Gothic art was a style that developed concurrently with Gothic architecture during the mid-12th century. Primary media in the Gothic period included sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco, and illuminated manuscripts. The earliest Gothic art existed as monumental sculpture on the walls of cathedrals and abbeys. Elaborate sculpture was used extensively to decorate the facades of these buildings.

Aside from monumental sculpture, smaller, portable sculptural pieces were also popular during the Gothic period. Small carvings, made generally for the lay market, became a considerable industry in urban centers. Gothic sculptures independent of architectural ornament were primarily created as devotional objects for the home or intended as donations for local churches. Nevertheless, small reliefs in ivory, bone, and wood covered both religious, as well as secular subjects, and were for church and domestic use. Such sculptures were often the work of urban artisans. The most typical subject for three dimensional small statues is the Virgin Mary alone or with child. Additional objects typical of the time included small devotional polyptychs, single figures, especially of the Virgin Mary, mirror-cases, combs, and elaborate caskets with scenes from romances.

It is hard to look at the Röttgen Pietà and not feel something—perhaps revulsion, horror, or distaste. It is terrifying and the more you look at it, the more intriguing it becomes. This is part of the beauty and drama of Gothic art, which aimed to create an emotional response in medieval viewers.

Earlier medieval representations of Christ focused on his divinity. In these works of art, Christ is on the cross, but never suffers. These types of crucifixion images are a type called Christus triumphans or the triumphant Christ. His divinity overcomes all human elements and so Christ stands proud and alert on the cross, immune to human suffering.

In the later Middle Ages, a number of preachers and writers discussed a different type of Christ who suffered in the way that humans suffered. This was different from Catholic writers of earlier ages, who emphasized Christ’s divinity and distance from humanity. Late medieval devotional writing (from the 13th-15th centuries) leaned toward mysticism and many of these writers had visions of Christ’s suffering. Francis of Assisi stressed Christ’s humanity and poverty, while others imagined Mary’s thoughts as she held her dead son. It wasn’t long before artists began to visualize these new devotional trends.

The effects of this new devotional style, which emphasized the humanity of Christ, quickly spread throughout western Europe through the rise of new religious orders (the Franciscans, for example) and the popularity of their preaching. It isn’t hard to see the appeal of the idea that God understands the pain and difficulty of being human. In the Röttgen Pietà, Christ clearly died from the horrific ordeal of crucifixion, but his skin is taut around his ribs, showing that he also led a life of hunger and suffering.

Röttgen Pietà

Pietà statues appeared in Germany in the late 1200s and were made in this region throughout the Middle Ages. Many examples of Pietàs survive today. Many of those that survive today are made of marble or stone, but the Röttgen Pietà is made of wood and retains some of its original paint. The Röttgen Pietà is the most gruesome of these extant examples.

Many of the other Pietàs also show a reclining dead Christ with three dimensional wounds and a skeletal abdomen. One of the unique elements of the Röttgen Pietà is Mary’s response to her dead son. She is youthful and draped in heavy robes like many of the other Mary’s, but her facial expression is different. In Catholic tradition, Mary had a special foreknowledge of the resurrection of Christ and so to her, Christ’s death is not only tragic. Images that reflect Mary’s divine knowledge show her at peace while holding her dead son. Mary in the Röttgen Pietà appears to be angry and confused. She doesn’t seem to know that her son will live again. She shows strong negative emotions that emphasize her humanity, just as the representation of Christ emphasizes his.

All of these Pietàs were devotional images and were intended as a focal point for contemplation and prayer. Even though the statues are horrific, the intent was to show that God and Mary, divine figures, were sympathetic to human suffering, and to the pain, and loss experienced by medieval viewers. By looking at the Röttgen Pietà, medieval viewers may have felt a closer personal connection to God by viewing this representation of death and pain.

Gothic Painting

The transition from the Romanesque to the Gothic style of painting happened quite slowly in Italy, several decades after it had first taken hold in France. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, the influx of Byzantine paintings and mosaics increased greatly. This was partly the reason that Italy was strongly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting. The initial changes to the Byzantine-inspired Romanesque style were quite small, marked merely by an increase in Gothic ornamental detailing rather than a dramatic difference in the style of figures and compositions.

Illuminated manuscripts provide excellent examples of Gothic painting. A prayer book, known as the book of hours, became increasingly popular during the Gothic age and was treated as a luxury item. The Hours of Mary of Burgundy, produced in Flanders c. 1477, contains a miniature showing Mary of Burgundy in devotion with a wonderful depiction of a French Gothic Cathedral behind her.

The Bible moralisée, or moralized bibles, are a small group of illustrated bibles that were made in thirteenth-century France and Spain. These books are among the most expensive medieval manuscripts ever made because they contain an unusually large number of illustrations.

Imagine a children’s illustrated bible. There might be 2-3 illustrations for each story: Adam and Eve in the garden, Noah’s ark, Daniel in the lion’s den, and others. If you open a regular copy of the bible, each of these stories are covered in several pages of densely written ancient text. Now imagine that you had a book that contained a separate illustration for every few sentences in the entire bible. Imagine that this super illustrated bible also contained another text that interpreted the bible text and that your book also contained illustrations of that additional text. One book: thousands of illustrations.

Bible moralisée contain two texts: the biblical text and the commentary text, which is sometimes called a gloss. These commentary texts interpreted the biblical text for the thirteenth century reader. Commentary authors often created comparisons between people and events in the biblical world and people and events in the medieval world. In the case of the Bible moralisée, the commentary often draws parallels between the bad guys of the biblical text and those who were perceived as bad guys in the thirteenth century. In France, as in most of western Europe at this time, Jews and corrupt priests were the bad guys and there are anti-semitic themes throughout the commentary and illustrations.

The format of Bible moralisée manuscripts is unusual, as the artist had to create a coherent arrangement for the biblical text, its accompanying commentary text, and an illustration for each. On each page of this manuscript there are eight circles, called roundels, that illustrate biblical scenes and commentary scenes. There are short snippets of text, either from the bible or commentary, that accompany each scene.

The example presented here is from the Paris-Oxford-London Bible moralisée, which is broken up into three volumes in three different cities. This page, or folio[7], is from the Apocalypse, or Book of Revelation. The text tells the story of John’s vision, where an angel takes him on a tour of heaven and shows him everything that will happen until the end of time, but in symbols. The gist of the story is that there is an ongoing battle between God and evil and ultimately God and his angels win.

In looking at the page, it breaks down into a number of parts and it is important to identify each part in order to understand how the texts and images work together. The Latin text in the upper left is from Revelation 14:19, which translates as:

And the angel thrust in his sharp sickle into the earth, and gathered the vineyard of the earth, and cast it into the great press of the wrath of God.” (Douay-Rheims translation)

The illustration is a visual interpretation of this text, with some extra details added. A figure on the right harvests grapes from the vines on the right and Christ, with his cruciform (cross-shaped) halo, pours the grapes from the basket on his back into the winepress. God and his angels bless the scene from above.

The commentary begins with the red letter “P” and talks about how the great winepress signifies hell. In the accompanying illustration, there are demons herding the damned into a hellmouth—literally the jaws of hell. Among the damned is a corrupt bishop, identified by his special hat, the mitre. There is also a corrupt king in hell.

This arrangement gives the biblical text three interpretations: a visual interpretation, a commentary interpretation, and a visual commentary interpretation. Each interpretation builds on the other. The illustrations are more than simple representations of the text, they are contemporary interpretations of it. The commentary text does not mention bishops or kings, but the illustrator adds those.

The reader then moves on to the right, to the next pairing of images and text, which comes from Revelation 15:1, which translates as:

And I saw another sign in heaven, great and wonderful: seven angels having the seven last plagues. For in them is filled up the wrath of God.” (Douay-Rheims translation)

The accompanying illustration shows Christ on the left and seven angels on the right.

The commentary beginning with the blue letter “P”, interprets the seven angels as faithful preachers who teach God’s people. The illustration shows priests on the left teaching a group of men. The illustrator goes further and adds two Jewish men on the right, identified by their conical hats. The faithful priests are contrasted with the Jewish men who literally turn their bodies away from the priests. Illustrations like this tried to convince Christian readers that although Jews were once God’s people, as outlined in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, that medieval Jews had turned away from that role. This kind of anti-semitic message promoted hate and violence toward Jews in the later Middle Ages.

- a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes. ↵

- the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the Christian Roman Empire of the fourth century. ↵

- The Ottonian empire encompassed the lands that now are Germany, Switzerland, northern and central Italy, but not the vast French territories that Charlemagne had held. ↵

- the law, which God gave to the Israelites through Moses, according to the Old Testament. ↵

- This Romanesque type can be traced back to Byzantine depictions of Mary as Theotokos, or the Mother of God. ↵

- Before the term “Gothic” came into common use, it was known as the “French Style.” ↵

- used in terms of page numbering for some books and manuscripts that are bound without listed page numbers, using "recto" and "verso" to designate the first (right/front) and second (left/back) sides. ↵

the study of the Church, the origins of Christianity, its relationship to Jesus, its role in salvation, its polity, its discipline, its eschatology, and its leadership.

an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in place or separated by metal strips or wire, normally of gold.

an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangible memorial.

the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group.

a formally prepared document where the text is often supplemented with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations.

the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term codex is often used for ancient manuscript books, with handwritten contents. Some codices, particularly Mayan and Aztec, are long sheets of paper or animal skin folded into pages.

an enlarged letter at the beginning of a paragraph or other section of text, that contains a picture.

the opening words of a text, manuscript, early printed book, or chanted liturgical text.

literally "a place for writing", is commonly used to refer to a room in medieval European monasteries devoted to the writing, copying and illuminating of manuscripts commonly handled by monastic scribes.

or service book, is a book published by the authority of a church body that contains the text and directions for the liturgy of its official religious services.

a traveler (literally "one who has come from afar") who is on a journey to a holy place.

a church to which pilgrimages are regularly made, or a church along a pilgrimage route.

an opening in a wall of a building, gate or fortification, especially a grand entrance to an important structure.

decorated with leaves or leaflike motifs.

standing free with all sides shown, rather than carved in relief against a ground.

the face of a building, especially the principal front that looks onto a street or open space.

a painting, typically an altarpiece, consisting of more than three leaves or panels joined by hinges or folds.

a Christian devotional book used to pray the canonical hours. The use of a book of hours was especially popular in the Middle Ages and as a result, they are the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript.

heavily illustrated, and extremely expensive, illuminated manuscripts of the thirteenth century. Though large, the manuscripts only contained selections of the text of the Bible, along with allegorical and moral deductions drawn from these passages.