2 Mesopotamia: a Cradle of Civilization

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key works of art and differentiate between the arts of the Ancient Near East

- Explain how the ancient art of the Mesopotamia embodied the power, prestige, and achievements of a series of ancient Near Eastern rulers.

Looking Forward

The “Urban Revolution” begins first in the “fertile crescent” of Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and Egypt c. 3,500–3000 BC. It forms the symbolic boundary between prehistory and history and during it mankind invented “civilization”—the development of permanent systems of social regulation; the beginning of infighting for control of these regulated resources; social bonds, social welfare; law; transport; irrigation; agriculture; food surplus; and settlement.Mesopotamia (from the Greek ‘mesos’ = between and ‘potamos’ = river; literally ‘[land] between rivers), the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (in modern day Iraq), is often referred to as the cradle of civilization because it is the first place where complex urban centers grew. The history of Mesopotamia, however, is inextricably tied to the greater region, which is comprised of the modern nations of Egypt, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, the Gulf states and Turkey. We often refer to this region as the Near or Middle East.

Why is this region named this way? What is it in the middle of or near to? It is the proximity of these countries to the West (to Europe) that led this area to be termed “the near east.” Ancient Near Eastern Art has long been part of the history of Western art, but history didn’t have to be written this way. It is largely because of the West’s interests in the Biblical “Holy Land” that ancient Near Eastern materials have been regarded as part of the Western canon of the history of art. An interest in finding the locations of cities mentioned in the Bible (such as Nineveh and Babylon) inspired the original English and French 19th century archaeological expeditions to the Near East. These sites were rediscovered, and their excavations revealed to the world a style of art which had been lost.

The Middle-Chronology

A universally accepted chronology for the entire ancient Near East remains to be established. On the basis of the Royal Canon of Ptolemy, a second century C.E. astronomer, regnal dates can be determined with certainty in Babylonia only as far back as 747 B.C.E. (the accession of King Nabonassar). Using excavated royal annals and chronicles, together with lists of annually appointed limmu-officials, the chronology of Assyria can be confidently extended back to 911 B.C.E. (the accession of King Adad-nirari II), and the earliest certain link with Egypt is 664 B.C.E. (the date of the Assyrian sack of the Egyptian capital at Thebes). Although it is often possible to locate earlier events quite precisely relative to each other, neither surviving contemporary documents nor scientific dating methods such as carbon 14, dendrochronology, thermoluminescence, and archaeoastronomy are able to provide the required accuracy to fix these events absolutely in time. For this course we shall employ the common practice of using, without prejudice, the so-called Middle Chronology, where events are dated relative to the reign of King Hammurabi of Babylon, which is defined as being ca. 1792–1750 B.C.E.

Civilizations of the Bronze Age

By 8000 B.C.E., agricultural communities are already established in northern Mesopotamia, the eastern end of the Fertile Crescent. Early in the sixth millennium B.C.E., farming communities, relying on irrigation rather than rainfall, settle ever further south along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Many societies rose and fell during the period we designate as the Ancient Near East. Stability was fleeting and this most of the objects pertained to religion and rule.

Mesopotamia remains a region of stark geographical contrasts: vast deserts rimmed by rugged mountain ranges, punctuated by lush oases. Flowing through this topography are rivers and it was the irrigation systems that drew off the water from these rivers, specifically in southern Mesopotamia, that provided the support for the very early urban centers here.

Rather surprisingly, the region lacks large reserves of stone (for building), precious metals, and timber and, therefore, had to rely on the long-distance trade of its agricultural products to secure these materials. The large-scale irrigation systems and labor required for extensive farming was managed by a centralized authority. The early development of this authority, over large numbers of people in an urban center, is really what distinguishes Mesopotamia and gives it a special position in the history of Western culture.

Sumer

In ancient Mesopotamia, agriculture was the basis for wealth and religion played a central role in government and daily life. The region of southern Mesopotamia is known as Sumer, and it is here that we find some of the oldest known cities, including Ur and Uruk. In fact, the Sumerians are credited with many firsts: the wheel, the plow, casting objects in copper and bronze, and cuneiform writing.

It is almost impossible to imagine a time before writing. However, you might be disappointed to learn that writing was not invented to record stories, poetry, or prayers to a god. The first fully developed written script, cuneiform, was invented to account for something unglamorous, but very important—surplus commodities: bushels of barley, head of cattle, and jars of oil!

The origin of written language (c. 3200 B.C.E.) was born out of economic necessity and was a tool of the theocratic (priestly) ruling elite who needed to keep track of the agricultural wealth of the city-states. Very few cuneiform signs have only one meaning; most have as many as four. Cuneiform signs could represent a whole word or an idea or a number. Most frequently though, they represented a syllable. Probably because of this extraordinary flexibility, the range of languages that were written with cuneiform across history of the Ancient Near East is vast and includes Sumerian, Akkadian, Amorite, Hurrian, Urartian, Hittite, Luwian, Palaic, Hatian and Elamite.

Prehistory ends with the establishment of the city of Uruk, where we find some of the earliest written records. This large city-state (and its environs) was largely dedicated to agriculture and eventually dominated southern Mesopotamia. Within the city of Uruk, there was a large temple complex dedicated to Innana, the patron goddess of the city. The City-State’s agricultural production would be “given” to her and stored at her temple. Harvested crops would then be processed (grain ground into flour, barley fermented into beer) and given back to the citizens of Uruk in equal share at regular intervals.

The head of the temple administration, the chief priest of Innana, also served as political leader, making Uruk the first known theocracy, and the state officials operate on the god’s behalf. We know many details about this theocratic administration because the Sumerians left numerous documents in the form of tablets written in cuneiform script.

Ziggurats were not only a visual focal point of the city, but they were also a symbolic one as well—they were at the heart of the theocratic political system. So, seeing the ziggurat towering above the city, one made a visual connection to the god or goddess honored there, but also recognized that deity’s political authority.

The ziggurat is the most distinctive architectural invention of the Ancient Near East. Like an ancient Egyptian pyramid, an ancient Near Eastern ziggurat has four sides and rises up to the realm of the gods. However, unlike Egyptian pyramids, the exterior of Ziggurats were not smooth but tiered to accommodate the work which took place at the structure as well as the administrative oversight and religious rituals essential to Ancient Near Eastern cities. Ziggurats are found scattered around what is today Iraq and Iran and stand as an imposing testament to the power and skill of the ancient culture that produced them.

Ziggurat of Ur

One of the largest and best-preserved ziggurats of Mesopotamia is the great Ziggurat at Ur. Small excavations occurred at the site around the turn of the twentieth century, and in the 1920s Sir Leonard Woolley, in a joint project with the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum in London, revealed the monument in its entirety.

What Woolley found was a massive rectangular pyramidal structure, oriented to true North, 210 by 150 feet, constructed with three levels of terraces, standing originally between 70 and 100 feet high. Three monumental staircases led up to a gate at the first terrace level. Next, a single staircase rose to a second terrace which supported a platform on which a temple and the final and highest terrace stood. The core of the ziggurat is made of mud brick covered with baked bricks laid with bitumen, a naturally occurring tar. Each of the baked bricks measured about 11.5 x 11.5 x 2.75 inches and weighed as much as 33 pounds. The lower portion of the ziggurat, which supported the first terrace, would have used some 720,000 baked bricks. The resources needed to build the Ziggurat at Ur are staggering.

The Ziggurat at Ur and the temple on its top were built around 2100 B.C.E. by the king Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur for the moon god Nanna, the divine patron of the city-state. The structure would have been the highest point in the city by far and, like the spire of a medieval cathedral, would have been visible for miles around, a focal point for travelers and the pious alike. As the Ziggurat supported the temple of the patron god of the city of Ur, it is likely that it was the place where the citizens of Ur would bring agricultural surplus and where they would go to receive their regular food allotments. In antiquity, to visit the Ziggurat at Ur was to seek both spiritual and physical nourishment.

Clearly the most important part of the Ziggurat at Ur was the Nanna temple at its top, but this, unfortunately, has not survived. Some blue glazed bricks have been found which archaeologists suspect might have been part of the temple decoration. The lower parts of the ziggurat, which do survive, include amazing details of engineering and design. For instance, because the unbaked mud brick core of the temple would, according to the season, be alternatively more or less damp, the architects included holes through the baked exterior layer of the temple allowing water to evaporate from its core. Additionally, drains were built into the ziggurat’s terraces to carry away the winter rains.

The Ziggurat at Ur has been restored twice. The first restoration was in antiquity. The last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabodinus, apparently replaced the two upper terraces of the structure in the 6th century B.C.E. Some 2400 years later in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein restored the façade of the massive lower foundation of the ziggurat, including the three monumental staircases leading up to the gate at the first terrace. Since this most recent restoration, however, the Ziggurat at Ur has experienced some damage. During the recent war led by American and coalition forces, Saddam Hussein parked his MiG fighter jets next to the ziggurat, believing that the bombers would spare them for fear of destroying the ancient site. Hussein’s assumptions proved only partially true as the ziggurat sustained some damage from American and coalition bombardment.

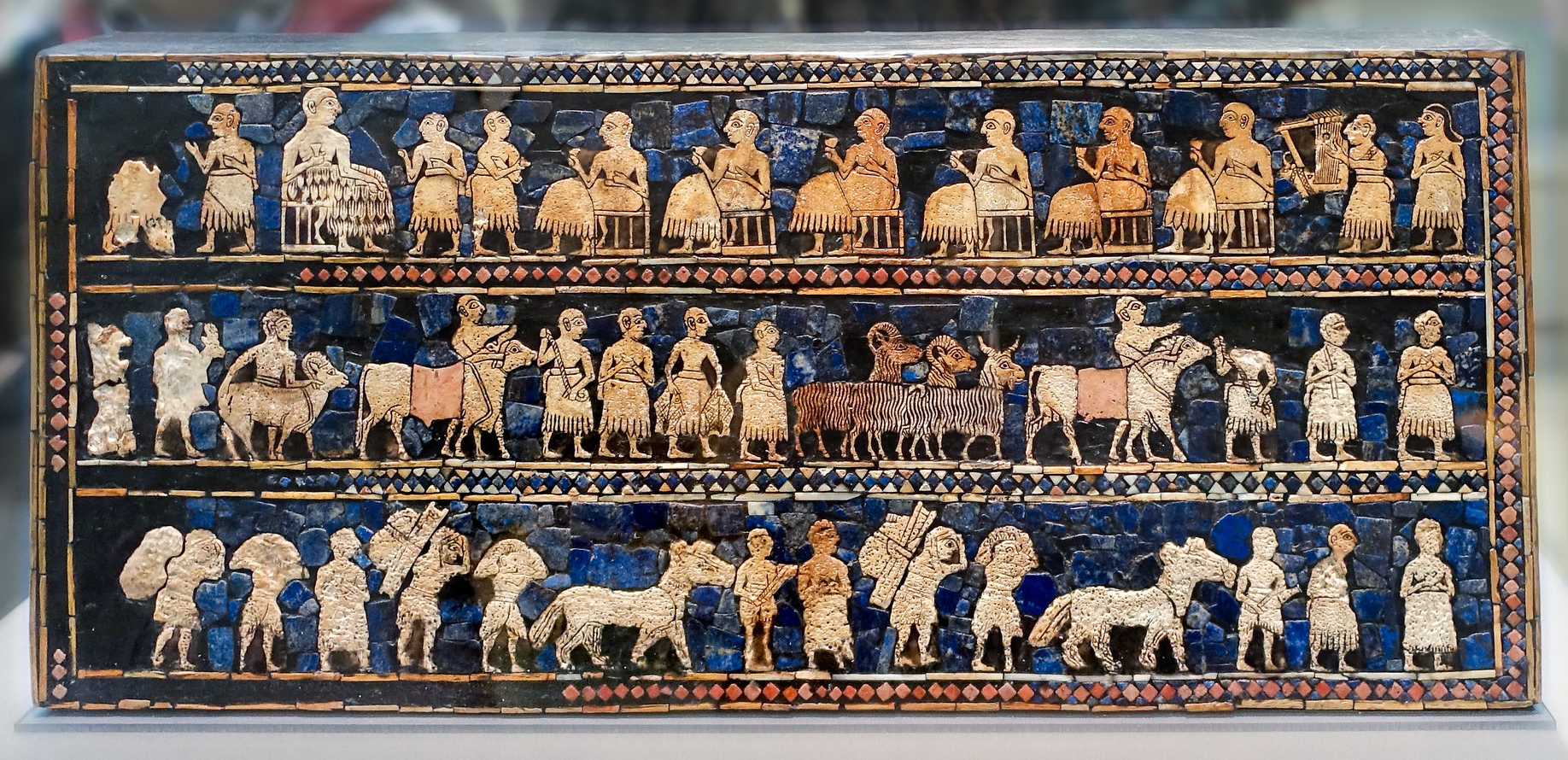

The Standard of Ur

Known today as Tell el-Muqayyar, the city-state of Ur is famous as the home of the Old Testament patriarch Abraham (Genesis 11:29-32), though there is no actual proof that Tell el-Muqayyar was identical with “Ur of the Chaldees.” Rulers of the later Kassite and Neo-Babylonian empires continued to build and rebuild at Ur, but changes in both the flow of the River Euphrates (now some ten miles to the east) and trade routes led to the eventual abandonment of the site.

Close to temple buildings at the center of the city of Ur, a cemetery site developed which included burials known today as the Royal Graves. Many of these contained very rich materials. In one area of the cemetery a group of sixteen graves was dated to the mid-third millennium. These large, shaft graves were distinct from the surrounding burials and consisted of a tomb, made of stone, rubble and bricks, built at the bottom of a pit. The layout of the tombs varied, some occupied the entire floor of the pit and had multiple chambers. The most complete tomb discovered belonged to a lady identified as Pu-abi from the name carved on a cylinder seal found with the burial.

The majority of graves had been robbed in antiquity but where evidence survived the main burial was surrounded by many human bodies. One grave had up to seventy-four such sacrificial victims. It is evident that elaborate ceremonies took place as the pits were filled in that included more human burials and offerings of food and objects. The excavator, Leonard Woolley thought the graves belonged to kings and queens. Another suggestion is that they belonged to the high priestesses of Ur.

In one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above the right shoulder of a man, was discovered the artifact known today as the Standard of Ur. Its original function is not yet understood, but Leonard Woolley, the excavator at Ur, imagined that it was carried on a pole as a standard, hence its common name. Another theory suggests that it formed the soundbox of a musical instrument.

When found, the original wooden frame for the mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli had decayed, and the two main panels had been crushed together by the weight of the soil. The bitumen acting as glue had disintegrated and the end panels were broken. As a result, the present restoration is only a best guess as to how it originally appeared.

The main panels are known as “War” and “Peace.” “War” shows one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army. Chariots, each pulled by four donkeys, trample enemies; infantry with cloaks carry spears; enemy soldiers are killed with axes, others are paraded naked and presented to the king who holds a spear.

The “Peace” panel depicts animals, fish and other goods brought in procession to a banquet. Seated figures, wearing woolen fleeces or fringed skirts, drink to the accompaniment of a musician playing a lyre.

War and Peace on the Standard of Ur

Akkad

By the end of the third millennium B.C.E., competition between the loose collective of city-states in Sumer and their northern neighbors in Akkad created two centralized regional powers. This centralization was militaristic in nature, and the art of this period generally became more martial. By 2334 B.C.E., Sumer would fall under the dominion of the Akkadian Empire’s King Sargon, a man from a lowly family who rose to power and founded the royal city of Akkad [1].

A major work illustrating the imperial art of the Akkadian Dynasty, the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, celebrates the triumph of King Naram-Sin over a mountain people, the Lullubi. The Akkadian king led his troops over the steep slopes of the enemy territory, mercilessly crushing all resistance. The conqueror’s victory march is coupled with the personal ascension of a sovereign who could now claim equal footing with the gods.

The brilliance of Naram-Sin’s reign is reflected in the execution of this stele, which commemorated his victory over Satuni, king of the Lullubi. For the first time, the sculptor rejected the traditional division of carvings into layered registers, opting instead for a unified and dynamic composition built around the glorified figure of the sovereign.

The Akkadian army is climbing the steep slopes of the Zagros Mountains, home to the Lullubi. This upward march sweeps aside all resistance. To the right of a line of trees clinging to the mountainside, defeated enemies are depicted in a posture of submission. Those who have been killed are trampled underfoot by the Akkadian soldiers or drop over the precipice. These mountain people are clad in a tunic of hide and wear their long hair tied back.

The composition is dominated by the lofty figure of the king, to whom all eyes – those of the Akkadian soldiers and of their Lullubi enemies – are turned. The triumphant sovereign, shown taller than the other men in the traditional manner (a convention known as hieratic scale), leads his army in the attack on the mountain. He is followed by standard bearers who march before helmeted soldiers carrying bows and axes. Naram-Sin tramples the bodies of his enemies, while a kneeling Lullubi tries to tear out the arrow piercing his throat. Another raises his hands to his mouth, begging the Akkadian king for mercy. But the conqueror’s gaze is directed toward the top of the mountain. Above Naram-Sin, solar disks seem to radiate their divine protection toward him, while he rises to meet them. The Akkadian sovereign wears a conical helmet with horns – a symbol traditionally the privilege of the gods – and is armed with a large bow and an axe.

This victorious ascension chiseled in stone thus celebrates a sovereign who considers himself on an equal footing with the gods. In official inscriptions, Naram-Sin’s name was therefore preceded with a divine determinative. He pushed back the frontiers of the empire farther than they had ever been, from Ebla in Syria to Susa in Elam, and led his army “where no other king had gone before him.” He now appears as a universal monarch, as proclaimed by his official title “King of the Four Regions” – namely, of the whole world.

Victory Stele of Naram Sin

Babylon

The city of Babylon on the River Euphrates in southern Iraq is mentioned in documents of the late third millennium B.C.E. and first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi (about 1790-1750 B.C.E.). He established his control over many other kingdoms stretching from the Persian Gulf to Syria.

Perhaps the most famous work of art from the early second millennium B.C. is the highly polished black basalt stele of the Babylonian king Hammurabi uncovered by archaeologists at Susa in 1902—the so-called Code of Hammurabi.

Just one year after the conquest of the city of Isin by predeceasing king Rim-Sin, a ruler named Hammurabi (r. ca. 1792–1750 B.C.) ascended the throne of Babylon. Kings of Babylon had been slowly amassing a small territory in central Mesopotamia, and Hammurabi intensified that effort with stunningly successful results. In some thirty short years, he gained control over much of northern and western Mesopotamia and by 1776 B.C.E., he is the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.”

Documents show Hammurabi was a cunning diplomat, a brilliant strategist, and a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule. Hammurabi also memorialized himself as a pious ruler, builder, and lawmaker—the ideal king. His success transformed Babylon from a city of little importance into the political (and later religious) capital of Mesopotamia. This is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god. Rulers throughout Mesopotamian history were careful to depict themselves as divinely appointed, just kings, and King Hammurabi was no different. Carved on top with an image of the king standing before Shamash, the sun god and god of justice, and beautifully engraved with hundreds of legal decisions, this monumental stele publicly declares Hammurabi’s divinely sanctioned juridical power. Although Shamash appears on the top of the monument, the prologue of the text as well as other works of art attest to the new importance of the god Marduk, who was tied to Babylon as its chief deity for the rest of Babylon’s history.

The Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi

Standing at approximately 7 feet tall, the Stele of Hammurabi is the first systematic codification of his people’s rights, duties, penalties for infringements. There are three hundred or so entries, some dealing with commercial and property matters, others with domestic problems and physical assault. (See this Yale translation, which offers great background context as well as the code translated in full.)

The Iron Age in the Ancient Near East

Around 1500 B.C.E. the city of Babylon would temporarily fall under the control of a dynasty of Kassite kings, originally from the Zagros mountains to the north, who sought to imitate Mesopotamian styles of art.

The Kassites themselves would eventually succumb to the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E., a period often referred to as the Late Bronze Age Collapse or ‘the first Dark Ages’ (this regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece and as great as Egypt, and was a period characterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, most likely, plague).

Babylonia had an uneasy relationship with its northern neighbor Assyria and opposed its military expansion. After centuries of struggle in Southern Mesopotamia among Sumer, Akkad, and Lagash, the Assyrians rise to dominance in Northern Mesopotamia, coming to power in 1400 BCE and controlling most of Mesopotamia by the ninth century BCE. In 689 B.C.E. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrians but as the city was highly regarded it was restored to its former status soon after. By around 600 B.C.E., the Assyrian Empire came to an end.

Assyria

After centuries of struggle in Southern Mesopotamia among Sumer, Akkad, and Lagash, the Assyrians rise to dominance in Northern Mesopotamia, coming to power in 1400 BCE. By the ninth century BCE the Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East. Led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings, their palaces were decorated with scenes of battles, Assyrian victories, presentations of tribute to the king, combat between men and beasts, and religious imagery. Assyrian society was entirely military focused, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies’ houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamour; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Assurnasirpal II (who reigned in the early 9th century), to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet.

Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions

Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength and skill. The Assyrian kings expected their greatness to be recorded, and they commissioned sculptors to create a series of narrative reliefs exalting royal power and piety. One of the earliest and most extensive forms of narrative relief found before the Roman Empire, these narratives recorded battles but also conquests of wild animals. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

Neo-Babylon

After 612 B.C.E. the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II were able to claim much of the Assyrian empire and rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt Babylon in the sixth century B.C.E. and it became the largest ancient settlement in Mesopotamia. This period is called Neo-Babylonian (or new Babylonia).

The visual history of the Ancient Near East is peppered with the rise and fall of rulers and city-states, which is one reason why such rulers were keen to immortalize themselves in architecture and art. In the art of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, we see an effort to invoke the styles and iconography of the 3rd millennium rulers of Babylonia. In fact, one Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, found a statue of Sargon of Akkad, set it in a temple and provided it with regular offerings.

The Neo-Babylonians are most famous for their architecture, notably at their capital city, Babylon. The most renowned of the Babylonian kings was Nebuchadnezzar II (r. c. 605–562 BCE), whose exploits the biblical book of Daniel recounts, and who is notorious today for his suppression of the Jews. Nebuchadnezzar II largely rebuilt this ancient city including its walls and seven gates. It is also during this era that Nebuchadnezzar II purportedly built[2]. the “Hanging Gardens of Babylon” for his wife because she missed the gardens of her homeland in Media (modern day Iran).

The Ishtar Gate and Processional Way

Like many rulers across time, Nebuchadnezzar II used architecture as a way to demonstrate his power, and the jewel in the crown of his building campaign was the Ishtar Gate. The Ishtar Gate (major portions of which are held today in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin) was the most elaborate of the inner-city gates constructed in Babylon in antiquity. Dedicated to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar, the whole gate was covered in rare lapis lazuli-glazed bricks, which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine. Alternating rows of lion and cattle march in a relief procession across the gleaming blue surface of the gate.

The king had left instructions in cuneiform script on tablets of clay in which he urged his successors to repair his royal edifices, which for identification purposes, had bricks inserted in the walls, with an inscription announcing that they were the work of “Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon from far sea to far sea.” Today, new inscribed bricks relay that the New Babylon was “rebuilt in the era of the leader Saddam Hussein” (a smaller reproduction of the gate was built in Iraq under Saddam Hussein as the entrance to a museum that has not been completed. Damage to this reproduction has occurred since the Iraq War). Today, rulers all over the world in many different cultures still use architecture to demonstrate their power as Hussein did, linking his rule with an ancient, grand era in Iraq’s history.

Persia

Although Nebuchadnezzar had boasted that “I had caused a mighty wall to circumscribe Babylon…so that the enemy who would do evil would not threaten,” Cyrus of Persia captured the city in the sixth century BCE. Babylon was but one of the Persian conquests. Egypt fell to them in 525 BCE, and by 480 BCE, the Persian Empire was the largest the world had yet known extending from the Indus River in southeastern Asia to the Danube in northeastern Europe.

The heart of ancient Persia is in what is now southwest Iran, in the region called the Fars. In the second half of the 6th century B.C.E., the Persians (also called the Achaemenids) created an enormous empire reaching from the Indus Valley to Northern Greece and from Central Asia to Egypt.

Although the surviving literary sources on the Persian empire were written by ancient Greeks who were the sworn enemies of the Persians and highly contemptuous of them, the Persians were in fact quite tolerant and ruled a multi-ethnic empire. Persia was the first empire known to have acknowledged the different faiths, languages and political organizations of its subjects.

This tolerance for the cultures under Persian control carried over into administration. In the lands which they conquered, the Persians continued to use indigenous languages and administrative structures. For example, the Persians accepted hieroglyphic script written on papyrus in Egypt and traditional Babylonian record keeping in cuneiform in Mesopotamia. The Persians must have been very proud of this new approach to empire as can be seen in the representation of the many different peoples in the reliefs from Persepolis, a city founded by Darius the Great in the 6th century B.C.E.

The Achaemenid Empire (First Persian Empire) was an imperial state of Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great and flourishing from c. 550-330 B.C.E. The empire’s territory was vast, stretching from the Balkan peninsula in the west to the Indus River valley in the east. The Achaemenid Empire is notable for its strong, centralized bureaucracy that had at its head, a king and relied upon regional satraps (regional governors).

A number of formerly independent states were made subject to the Persian Empire. These states covered a vast territory from central Asia and Afghanistan in the east to Asia Minor, Egypt, Libya, and Macedonia in the west. The Persians famously attempted to expand their empire further to include mainland Greece, but they were ultimately defeated in this attempt. By the early fifth century B.C.E. the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire ruled an estimated 44% of the human population of planet Earth.

The Persian Empire ended, famously, with the death of Darius III in 330 BCE at the hands of Alexander the Great, king of Macedonia. Alexander no doubt was impressed by the Persian system of absorbing and retaining local language and traditions as he imitated this system himself in the vast lands he won in battle. Indeed, Alexander made a point of burying Darius III in a lavish and respectful way in the royal tombs near Persepolis. This enabled Alexander to claim title to the Persian throne and legitimize his control over the greatest empire of the Ancient Near East.

a political system consisting of an independent city having sovereignty over contiguous territory and serving as a centre and leader of political, economic, and cultural life.

a system of government in which priests rule in the name of God or a god.

a rectangular stepped tower, sometimes surmounted by a temple. Ziggurats are first attested in the late 3rd millennium BC and probably inspired the biblical story of the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1–9).

A visual method of marking the significance of a figure through its size. The more important a figure is, the larger it appears.