5 Rise of an Empire: Etruria and the Roman World

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify key works of art and differentiate the arts of ancient Italy.

- Identify major trends and monuments of imperial Roman art and architecture.

Looking Forward

In legend, Rome was founded in 753 B.C.E. by Romulus, its first king. In 509 B.C.E. Rome became a republic ruled by the Senate (wealthy landowners and elders) and the Roman people. During the 450 years of the republic, Rome conquered the rest of Italy and then expanded into France, Spain, Turkey, North Africa and Greece.

However, before the small village of Rome became “Rome” with a capital R, a brilliant civilization once controlled almost the entire peninsula we now call Italy. This was the Etruscan civilization, a vanished culture whose achievements set the stage not only for the development of ancient Roman art and culture but for the Italian Renaissance as well.

The Etruscans

Though you may not have heard of them, the Etruscans were the first “superpower” of the Western Mediterranean who, alongside the Greeks, developed the earliest true cities in Europe. They were so successful, in fact, that the most important cities in modern Tuscany (Florence, Pisa, and Siena to name a few) were first established by the Etruscans and have been continuously inhabited since then.

Yet the labels ‘mysterious’ or ‘enigmatic’ are often attached to the Etruscans since none of their own histories or literature survives. This is particularly ironic as it was the Etruscans who were responsible for teaching the Romans the alphabet and for spreading literacy throughout the Italian peninsula.

The Etruscan civilization thrived in central Italy during the first millennium B.C.E., Occupying the approximate area of present-day Tuscany—the region derives its name from the word ‘Etruscan’. During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E., the Etruscans became sea traders and actively participated in Mediterranean trade. The civilization also began to expand, and the Etruscans eventually settled as far north as the Po River and as far south as the Tiber River and the northern parts of Campania.

Aside from trade, a large part of Etruscan wealth came from the rich natural resources of the territories they lived in. The soil was fertile for agriculture and the land was rich with minerals and metals, which were mined. Etruscan cities and regions appear to have been ruled over by a king, and Etruscan kings are accounted for as the early rulers of Rome. While the Romans proudly remember overthrowing their Etruscan rulers, many aspects of Etruscan society were adopted by the Romans.

Since many Etruscan cities have been continually occupied since their foundation—first by the Etruscans, then the Romans, up to today—a majority of Etruscan archaeological sites are tombs and necropoleis. Archaeologists and historians rely on Etruscan funerary culture to derive ideas about the society’s culture, customs, and history.

What we do know is that the Etruscan influence on ancient Roman culture was profound, and it was from the Etruscans that the Romans inherited many of their own cultural and artistic traditions: from the spectacle of gladiatorial combat to hydraulic engineering, temple design, and religious ritual, among many other things. In fact, hundreds of years after the Etruscans had been conquered by the Romans and absorbed into their empire, the Romans still maintained an Etruscan priesthood in Rome. We may even derive our very common word ‘person’ from the Etruscan mythological figure ‘Phersu’—the frightful, masked figure you see in this Early Etruscan tomb painting (abovewho would engage his victims in a dreadful ‘game’ of bloodletting in order to appease the soul of the deceased.

Early on, the Etruscans developed a vibrant artistic and architectural culture, one that was often in dialogue with other Mediterranean civilizations. Trading of the many natural mineral resources found in Tuscany, the center of ancient Etruria, caused them to bump up against Greeks, Phoenicians and Egyptians in the Mediterranean. With these other Mediterranean cultures, they exchanged goods, ideas and, often, a shared artistic vocabulary.

The Temple of Menrva

Early on, the Etruscans developed a vibrant artistic and architectural culture, one that was often in dialogue with other Mediterranean civilizations. Trading of the many natural mineral resources found in Tuscany, the center of ancient Etruria, caused them to bump up against Greeks, Phoenicians and Egyptians in the Mediterranean. With these other Mediterranean cultures, they exchanged goods, ideas and, often, a shared artistic vocabulary.

Among the early Etruscans, the worship of the Gods and Goddesses did not take place in or around monumental temples as it did in early Greece or in the Ancient Near East, but rather, in nature. Early Etruscans created ritual spaces in groves and enclosures open to the sky with sacred boundaries carefully marked through ritual ceremony.

Around 600 B.C.E., however, the desire to create monumental structures for the gods spread throughout Etruria, most likely as a result of Greek influence. While the desire to create temples for the gods may have been inspired by contact with Greek culture, Etruscan religious architecture was markedly different in material and design. These colorful and ornate structures typically had stone foundations, but their wood, mudbrick and terracotta superstructures suffered far more from exposure to the elements. Greek temples still survive today in parts of Greece and southern Italy since they were constructed of stone and marble, but Etruscan temples were built with mostly ephemeral materials and have largely vanished.

Fortunately, an ancient Roman architect by the name of Vitruvius

[1] wrote about Etruscan temples in his book De architectura in the late first century B.C.E. In his treatise on ancient architecture, Vitruvius described the key elements of Etruscan temples, and it was his description that inspired Renaissance architects to return to the roots of Tuscan design and allows archaeologists and art historians today to recreate the appearance of these buildings.

Etruscans often, although not always, worshiped multiple gods in a single temple. In such cases, each god received its own cella that housed its cult statue. Often the three-cella temple would be dedicated to the principal gods of the Etruscan pantheon—Tinia, Uni, and Menrva (comparable to the Roman gods Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva).

The archaeological evidence that does remain from many Etruscan temples largely confirms Vitruvius’s description. One of the best explored and known of these is the Portonaccio Temple dedicated to the goddess Menrva (Roman=Minerva/Greek=Athena) at the city of Veii about 18 km north of Rome. The tufa-block foundations of the Portonaccio Temple still remain and their nearly square footprint reflects Vitruvius’s description of a floor plan with proportions that are 5:6, just a bit deeper than wide.

For much of their history, the Etruscans did not decorate their temples in the Greek manner with friezes or pedimental sculptures. Instead, they placed terracotta statues called akroteria along the roof’s ridge pool and on the peaks and edges of the pediment. Working with terracotta was a means for additive sculpture. Unlike the subtractive sculptural techniques employed in the carving of rock or stone, this allowed for subtle modeling and more expressive and dynamic features.

The Apulu of Veii

Perhaps most interesting about the Portonaccio temple is the abundant terracotta sculpture that still remains, the volume and quality of which is without parallel in Etruria (few examples of large-scale or monumental Etruscan sculptures survive). In addition to many terracotta architectural elements (masks, antefixes, decorative details), a series of over life-size terracotta sculptures have also been discovered in association with the temple. Originally placed on the ridge of temple roof, these figures seem to be Etruscan assimilations of Greek gods, set up as a tableau to enact some mythic event.

The most famous and well-preserved of these is the Apulu (the Etruscan equivalent of Apollo) of Veii, a dynamic, striding masterpiece of large-scale terracotta sculpture and likely a central figure in the rooftop narrative depicting the myth of Heracles and the Ceryneaian Hind[2]. His counterpart may have been the less well-preserved figure of Hercle (Hercules) with whom he struggled in an epic contest over the Golden Hind, an enormous deer sacred to Apollo’s twin sister Artemis. Other figures discovered with these suggest an audience watching the action. Whatever the myth may have been, it was a completely Etruscan innovation to use sculpture in this way, placed at the peak of the temple roof—creating what must have been an impressive tableau against the backdrop of the sky.

The figure of Apulu has several Greek characteristics. The face is similar to the faces of Archaic Greek kouroi figures. The face is simply carved, and an archaic smile provides a notion of emotion and realism. The hair of Apulu is stylized and falls across his shoulders and down his neck and back in stylized, geometric twists that seem to represent braids. The figure, like Greek figures, was painted in bright colors, and the edge of his toga appears to be lined in blue.

Unlike Archaic Greek statues and kouroi, the figure of Apulu is full of movement and presents the viewer with an entirely different aesthetic from the Greek style. The figure of Apulu is dynamic and flexible. He strides forward with an arm stretched out. He leans on his front foot, and his back foot is slightly raised.

The body is more faithfully modeled (comparable to later Greek kouroi), and instead of being nude, he wears a toga that is draped over one shoulder. The garment’s folds are patterned and stylized but cling to the body, allowing the viewer to clearly distinguish the god’s chest and thigh muscles. While the Etruscan artist applied an Archaic smile to Apulu, the figure’s lips are full, and his head is more egg-shaped than round—both characteristics of Etruscan art and sculpture.

Apulu (Apollo of Veii)

Rome: from Republic to Empire

Rome became very Greek influenced or “Hellenized,” filled with Greek architecture, literature, statues, wall-paintings, mosaics, pottery and glass. But with Greek culture came Greek gold, and generals and senators fought over this new wealth. The republic collapsed in civil war and the Roman empire began.

Ancient Roman art is a very broad topic, spanning almost 1,000 years and three continents, from Europe into Africa and Asia. The first Roman art can be dated back to 509 B.C.E., with the legendary founding of the Roman Republic, and lasted until 330 C.E. (or much longer, if you include Byzantine art). Roman art also encompasses a broad spectrum of media including marble, painting, mosaic, gems, silver and bronze work, and terracotta, just to name a few. The city of Rome was a melting pot, and the Romans had no qualms about adapting artistic influences from the other Mediterranean cultures that surrounded and preceded them. For this reason, it is common to see Greek, Etruscan and Egyptian influences throughout Roman art. This is not to say that all of Roman art is derivative, though, and one of the challenges for specialists is to define what is “Roman” about Roman art.

Greek art certainly had a powerful influence on Roman practice; the Roman poet Horace famously said that “Greece, the captive, took her savage victor captive,” meaning that Rome (though it conquered Greece) adapted much of Greece’s cultural and artistic heritage (as well as importing many of its most famous works). It is also true that many Romans commissioned versions of famous Greek works from earlier centuries; this is why we often have marble versions of lost Greek bronzes such as the Doryphoros by Polykleitos.

The Romans did not believe, as we do today, that to have a copy of an artwork was of any less value that to have the original. The copies, however, were more often variations rather than direct copies, and they had small changes made to them. The variations could be made with humor, taking the serious and somber element of Greek art and turning it on its head. So, for example, a famously gruesome Hellenistic sculpture of the satyr Marsyas being flayed was converted in a Roman dining room to a knife handle. A knife was the very element that would have been used to flay the poor satyr, demonstrating not only the owner’s knowledge of Greek mythology and important statuary, but also a dark sense of humor. It is precisely this ability to adapt, convert, combine elements and add a touch of humor that makes Roman art Roman.

The Roman Republic

Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighboring Etruscans, themselves greatly influenced by their Greek trading partners. As the expanding Roman Republic began to conquer Greek territory, its official sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style, with its departure from the idealized body and flair for the dramatic. This is partly due to the large number of Greek sculptors working within Roman territory.

In the Republican period, art was produced in the service of the state, depicting public sacrifices or celebrating victorious military campaigns. Portraiture extolled the communal goals of the Republic; hard work, age, wisdom, being a community leader and soldier. Patrons chose to have themselves represented with balding heads, large noses, and extra wrinkles, demonstrating that they had spent their lives working for the Republic as model citizens, flaunting their acquired wisdom with each furrow of the brow. We now call this portrait style veristic, referring to the hyper-naturalistic features that emphasize every flaw, creating portraits of individuals with personality and essence.

As with other forms of Roman art, portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subjects with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the faces of the portraits often display incredible detail and likeness, the subjects’ bodies are idealized and do not correspond to the age shown in the face.

The popularity and usefulness of verism appears to derive from the need to have a recognizable image. Veristic portrait busts provided a means of reminding people of distinguished ancestors or of displaying one’s power, wisdom, experience, and authority. Statues were often erected of generals and elected officials in public forums—and a veristic image ensured that a passerby would recognize the person when they actually saw them.

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish in the first century B.C.E.. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire, and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of the portraits and their use.

Veristic Male Portrait

The Early Empire: the birth of the Pax Romana

In 31 B.C.E. Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, defeated Cleopatra and Mark Antony at Actium. This brought the last civil war of the republic to an end. Although it was hoped by many that the republic could be restored, it soon became clear that a new political system was forming: the emperor became the focus of the empire and its people. Although, in theory, Augustus (as Octavian became known) was only the first citizen and ruled by consent of the Senate, he was in fact the empire’s supreme authority. As emperor he could pass his powers to the heir he decreed and was a king in all but name.

The empire, as it could now be called, enjoyed unparalleled prosperity as the network of cities boomed, and goods, people and ideas moved freely by land and sea. Many of the masterpieces associated with Roman art, such as the mosaics and wall paintings of Pompeii, gold and silver tableware, and glass were created in this period. The empire ushered in an economic and social revolution that changed the face of the Roman world: service to the empire and the emperor, not just birth and social status, became the key to advancement.

Starting with Augustus in 27 B.C.E., the emperors ruled for a total of five hundred years. They expanded Rome’s territory and by about 200 C.E., their vast empire stretched from Syria to Spain and from Britain to Egypt. Networks of roads connected rich and vibrant cities, filled with beautiful public buildings. A shared Greco-Roman culture linked people, goods and ideas.

Roman art was now put to the service of aggrandizing the ruler and his family. It was also meant to indicate shifts in leadership. Imperial art often hearkened back to the Classical[3] art of the past. During his reign, Augustus enacted an effective propaganda campaign to promote the legitimacy of his rule as well as to encourage moral and civic ideals among the Roman populace. Augustan sculpture contains the rich iconography of Augustus’s reign with its strong themes of legitimacy, stability, fertility, prosperity, and religious piety. The visual motifs employed within this iconography became the standards for imperial art.

Augustus had a strong interest in reshaping the Roman world (with him as the sole leader) but had to be cautious about how radical those changes seemed to the Roman populace. While he defeated enemies, both foreign and domestic, he was concerned about being perceived as too authoritarian–he did not wish to labeled as a king (rex) for fear that this would be too much for the Roman people to accept. So, the Augustan scheme involved a declaration that Rome’s republican government had been “restored” by Augustus and he styled himself as the leading citizen of the republic (princeps). These political and ideological motives then influence and guide the creation of his program of monumental art and architecture. These monumental forms, of which the Ara Pacis is a prime example, served to both create and reinforce these Augustan messages.

The Ara Pacis is, at its simplest, an open-air altar for blood sacrifice associated with the Roman state religion. The ritual slaughtering and offering of animals in Roman religion was routine, and such rites usually took place outdoors. Sacred offerings to the gods, consultations with priests and diviners, ritual formulae, communal feasting—were all practices aimed at fostering and maintaining social cohesion and communicating authority. It could perhaps be argued that the Ara Pacis Augustae—the Altar of Augustan Peace—represents in luxurious, stately microcosm the practices of the Roman state religion in a way that is simultaneously elegant and pragmatic.

Vowed on July 4, 13 B.C.E., and dedicated on January 30, 9 B.C.E., the monument stood proudly in the Campus Martius in Rome (a level area between several of Rome’s hills and the Tiber River), adjacent to architectural complexes that cultivated and proudly displayed messages about the power, legitimacy, and suitability of their patron—the emperor Augustus.

The significance of the topographical placement would have been quite evident to ancient Romans. This complex of Augustan monuments made a clear statement about Augustus’ physical transformation of Rome’s urban landscape. The dedication to a rather abstract notion of peace (pax) is significant in that Augustus advertises the fact that he has restored peace to the Roman state after a long period of internal and external turmoil.

The altar (ara) itself sits within a monumental stone screen that has been elaborated with bas-relief sculpture, with the panels combining to form a programmatic mytho-historical narrative about Augustus and his administration, as well as about Rome’s deep roots. The altar was the functional portion of the monument, the place where blood sacrifice and/or burnt offerings would be presented to the gods.

Ara Pacis Augustae

The implications of the Ara Pacis are far reaching. Originally located along the Via Lata (now Rome’s Via del Corso), the altar is part of a monumental architectural makeover of Rome’s Campus Martius carried out by Augustus and his family. Initially the makeover had a dynastic tone, with the Mausoleum of Augustus near the river. The dedication of the Horologium (sundial) of Augustus and the Ara Pacis, the Augustan makeover served as a potent, visual reminder of Augustus’ success to the people of Rome. The choice to celebrate peace and the attendant prosperity in some ways breaks with the tradition of explicitly triumphal monuments that advertise success in war and victories won on the battlefield. By championing peace—at least in the guise of public monuments—Augustus promoted a powerful and effective campaign of political message making.

The Middle Empire: the age of the “Five Good Emperors” (and one that was just ok)

Successive emperors of the Roman empire gradually expanded Rome’s territory, and by the time of the emperor Trajan in the late first century C.E., the Roman empire—with about fifty million inhabitants—encompassed the whole of the Mediterranean, Britain, much of northern and central Europe and the Near East. During this period of peace, stability, and an expansion of the empire’s borders, many of the emperors sought to cast themselves in the image of the first imperial builder, Augustus. The projects these emperors conducted around the empire included the building and restoration of roads, bridges, and aqueducts. This building program served the people of Rome by expanding public space, allocating places for trade and politics, and providing and improving the temples so the people could the serve the gods.

The Roman Pantheon probably doesn’t make popular shortlists of the world’s architectural icons, but it should: it is one of the most imitated buildings in history. It is a true architectural wonder. Described as the “sphinx of the Campus Martius”—referring to enigmas presented by its appearance and history, and to the location in Rome where it was built—to visit it today is to be almost transported back to the Roman Empire itself.

The Pantheon’s basic design is simple and powerful. A portico with free-standing columns is attached to a domed rotunda. While Roman architecture originally began as an imitation of Classical Greek architecture, it eventually evolved into a new style. Innovations, such as improvements to the round arch and barrel vault—as well as the inventions of concrete and the true hemispherical dome—allowed Roman architecture to become more versatile than its Greek predecessors.

One approaches the Pantheon through the portico with its tall, monolithic Corinthian columns of Egyptian granite. Originally, the approach would have been framed and directed by the long walls of a courtyard or forecourt in front of the building, and a set of stairs, now submerged under the piazza, leading up to the portico. Walking beneath the giant columns, the outside light starts to dim. As you pass through the enormous portal with its bronze doors, you enter the rotunda, where your eyes are swept up toward the oculus.

The Pantheon’s great interior spectacle—its enormous scale, the geometric clarity of the circle-in-square pavement pattern and the dome’s half-sphere, and the moving disc of light—is all the more breathtaking for the way one moves from the bustling square outside into the grandeur inside.

The structure itself is an important example of advanced Roman engineering. Its walls are made from brick-faced concrete—an innovation widely used in Rome’s major buildings and infrastructure, such as aqueducts—and are lightened with relieving arches and vaults built into the wall mass.

The Romans perfected the recipe for concrete during the third century B.C.E. by mixing together water, lime, and volcanic ash mined from the countryside surrounding Mt. Vesuvius. Concrete was a cheaper and lighter material than most other stones used for construction. This helped the Romans build structures that were taller, more complicated, and quicker to build than any previous ones. Furthermore, once dried, concrete was also extremely strong, yet flexible enough to remain standing during moderate seismic activity. The concrete of the dome is graded into six layers with a mixture of scoria, at the top. From top to bottom, the structure of the Pantheon was fine-tuned to be structurally efficient and to allow flexibility of design.

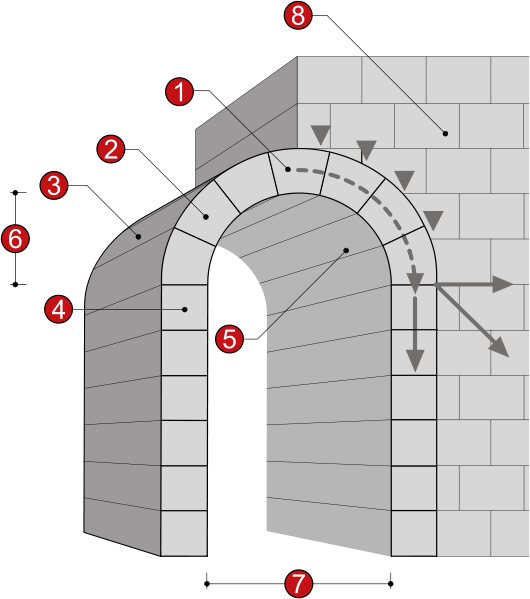

The Romans effectively combined concrete and the structural shape of the arch to bear immense weights, as arches are designed to redistribute weight from the top, towards the sides, and down into the ground. An arch is a pure compression form; it can span a large area by resolving forces into compressive stresses (pushing downward) that, in turn, eliminate tensile stresses (pushing outward). As the forces in the arch are carried to the ground, the arch will push outward at the base (called thrust). As the height of the arch decreases, the outward thrust increases. In order to maintain arch action and prevent the arch from collapsing, the thrust needs to be restrained, either with internal ties or external bracing.

The arch is a shape that can be manipulated into a variety of forms that create unique architectural spaces. Multiple arches can be used together to create a vault. The simplest type is known as a barrel vault. Barrel vaults consist of a line of arches in a row that create the shape of a tunnel. When two barrel vaults intersect at right angles, they create a groin vault. These are easily identified by the x-shape they create in the ceiling of the vault. Furthermore, because of the direction, the thrust is concentrated along this x-shape, so only the corners of a groin vault need to be grounded. This allows an architect or engineer to manipulate the space below the groin vault in a variety of ways. Arches and vaults can be stacked and intersected with each other in a multitude of ways. One of the most important forms that they can create is the dome. This is essentially an arch that is rotated around a single point to create a large hemispherical vault.

It is now an open question whether the building was ever a temple to all the gods, as its traditional name has long suggested to interpreters. Pantheon, or Pantheum in Latin, was more of a nickname than a formal title. One of the major written sources about the building’s origin is the Roman History by Cassius Dio, a late second- to early third-century historian who was twice Roman consul. His account, written a century after the Pantheon was completed, must be taken skeptically. However, he provides important evidence about the building’s purpose. He wrote:

He [Agrippa] completed the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens. Agrippa, for his part, wished to place a statue of Augustus there also and to bestow upon him the honor of having the structure named after him; but when Augustus wouldn’t accept either honor, he [Agrippa] placed in the temple itself a statue of the former [Julius] Caesar and in the ante-room statues of Augustus and himself. This was done not out of any rivalry or ambition on Agrippa’s part to make himself equal to Augustus, but from his hearty loyalty to him and his constant zeal for the public good.

A number of scholars have now suggested that the original Pantheon was not a temple in the usual sense of a god’s dwelling place, but instead may have been intended as a dynastic sanctuary (part of a ruler cult emerging around Augustus) with the original dedication being to Julius Caesar, the progenitor of the family line of Augustus and Agrippa and a revered ancestor who had been the first Roman deified by the Senate. Adding to the plausibility of this view is the fact that the site had sacred associations—tradition stating that it was the location of the apotheosis of Romulus, Rome’s mythic founder. Even more, the Pantheon was also aligned on axis, across a long stretch of open fields called the Campus Martius, with Augustus’ mausoleum, completed just a few years before the Pantheon. Agrippa’s building, then, was redolent with suggestions of the alliance of the gods and the rulers of Rome during a time when new religious ideas about ruler cults were taking shape.

The Pantheon

The symbolism of the great dome adds weight to this interpretation. The dome’s coffers are divided into 28 sections, equaling the number of large columns below. 28 is a “perfect number,” a whole number whose summed factors equal it (thus, 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28). Only four perfect numbers were known in antiquity (6, 28, 496, and 8128) and they were sometimes held—for instance, by Pythagoras and his followers—to have mystical, religious meaning in connection with the cosmos. Additionally, the oculus at the top of the dome was the interior’s only source of direct light. The sunbeam streaming through the oculus traced an ever-changing daily path across the wall and floor of the rotunda. Perhaps, then, the sunbeam marked solar and lunar events, or simply time. The idea fits nicely with Dio’s understanding of the dome as the canopy of the heavens and, by extension, of the rotunda itself as a microcosm of the Roman world beneath the starry heavens, with the emperor presiding over it all, ensuring the right order of the world.

There are also commemorative works like the triumphal arches and columns that served a didactic as well as a celebratory function. The arches and columns (like the Arch of Titus or the Column of Trajan), marked victories, depicted war, and described military life.

Marcus Ulpius Traianus, now commonly referred to as Trajan, reigned as Rome’s emperor from 98 until 117 C.E. A military man, Trajan was born of mixed stock—part Italic, part Hispanic—into the gens Ulpia (the Ulpian family) in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica (modern Spain) and enjoyed a career that catapulted him to the heights of popularity, earning him an enduring reputation as a “good emperor.”

Trajan was the first in a line of adoptive emperors that concluded with Marcus Aurelius. These emperors were chosen for the “job” based not on bloodlines, but on their suitability for rule. This period is often regarded as the height of the Roman empire’s prosperity and stability.

During his time as emperor, Trajan fought a series of campaigns known as the Dacian Wars. Dacia (modern Romania) was seen as a troublesome neighbor by the Romans, and the Dacians were seen to pose a threat to the province of Moesia, along the Danube frontier. In addition, Dacia was rich in natural resources (including gold), that were attractive to the Romans. The first campaign saw Trajan defeat the Dacian leader Decebalus in 101 C.E., after which the Dacians sought terms from the Romans. Renewed Dacian hostilities brought about the second Dacian War that concluded in 106 C.E.. Trajan’s victory was a substantial one—he declared over 100 days of official celebrations and the Romans exploited Dacia’s natural wealth, while incorporating Dacia as an imperial province.

After the first Dacian war Trajan earned the honorary epithet “Dacicus Maximus” (greatest Dacian) and a victory monument known as the Tropaeum Traiani (Trophy of Trajan) was built at Civitas Tropaensium (modern Adamclisi, Romania). The iconographic scheme of the column illustrates Trajan’s wars in Dacia. The lower half of the column corresponds to the first Dacian War (c. 101-102 C.E.), while the top half depicts the second Dacian War (c. 105-106 C.E.). The first narrative event shows Roman soldiers marching off to Dacia, while the final sequence of events portrays the suicide of the enemy leader, Decebalus, and the mopping up of Dacian prisoners by the Romans.

The execution of the frieze is meticulous, and the level of detail achieved is astonishing. While the column does not carry applied paint now, many scholars believe the frieze was initially painted. The sculptors took great care to provide settings for the scenes, including natural backgrounds, and mixed perspectival views to offer the maximum level of detail. Sometimes multiple perspectives are evident within a single scene. The overall, unifying theme is that of the Roman military campaigns in Dacia, but the details reveal additional, more subtle narrative threads.

One of the clear themes is the triumph of civilization (represented by the Romans) over its antithesis, the barbarian state (represented here by the Dacians). The Romans are orderly and uniform, the Dacians less so. The Romans are clean shaven, the Dacians are shaggy. The Romans avoid leggings, the Dacians wear leggings (like all good barbarians did—at least those depicted by the Romans).

Combat scenes are frequent in the frieze. The detailed rendering provides a nearly unparalleled visual resource for studying the iconography of the Roman military, as well as for studying the actual equipment, weapons, and tactics. There is clear ethnic typing as well, as the Roman soldiers cannot be confused for Dacian soldiers, and vice versa.

The emperor Trajan figures prominently in the frieze. Each time he appears, his position is commanding and the iconographic focus on his person is made clear. We see Trajan in various scenarios, including addressing his troops (ad locutio) and performing sacrifices. The fact that the figures in the scenes are focused on the figure of the emperor helps to draw the viewer’s attention to him.

The Column of Trajan may be contextualized in a long line of Roman victory monuments, some of which honored specific military victories and thus may be termed “triumphal monuments” and others that generally honor a public career and are thus “honorific monuments.” Among the earliest examples of such permanent monuments at Rome is the rostrate column (column rostrata) that was erected in honor of a naval victory celebrated by Caius Duilius after the battle of Mylae in 260 B.C.E. (this column does not survive).

Column of Trajan

The idea of the honorific column was carried forward by other victorious leaders—both in the ancient and modern eras. In the Roman world immediate, derivative monuments that draw inspiration from the Column of Trajan include the Column of Marcus Aurelius (c. 193 C.E.) in Rome’s Piazza Colonna, as well as the now lost he Column of Justinian at Constantinople (c. 543 C.E.). In more recent times, the columns honoring Admiral Horatio Nelson in London’s Trafalgar Square (c. 1843), Napoleon I in the Place Vendôme in Paris (c. 1810), and the Washington Monument of Baltimore, Maryland (1829) all were directly inspired by the Column of Trajan.

The Late Empire: descent “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust”

The imperial system of the Roman Empire depended heavily on the personality and standing of the emperor himself. The reigns of weak or unpopular emperors often ended in bloodshed at Rome and chaos throughout the empire as a whole. In the third century C.E. the very existence of the empire was threatened by a combination of economic crisis, weak and short-lived emperors and usurpers (and the violent civil wars between their rival supporting armies), and massive barbarian penetration into Roman territory.

Relative stability was re-established in the fourth century C.E., through the emperor Diocletian’s division of the empire. The empire was divided into eastern and western halves and then into more easily administered units. Although some later emperors such as Constantine ruled the whole empire, the division between east and west became more marked as time passed. Financial pressures, urban decline, underpaid troops and consequently overstretched frontiers – all of these finally caused the collapse of the western empire under waves of barbarian incursions in the early fifth century C.E. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed in 476 C.E., though the empire in the east, centered on Byzantium (Constantinople), continued until the fifteenth century.

Later Imperial art moved away from earlier Classical influences, shifting toward art that emphasized frontality, stiffness of pose and drapery, deeply drilled lines, less naturalism, squat proportions and lack of individualism. Important figures are often slightly larger or are placed above the rest of the crowd to denote importance. For example, on the oratio relief panel on the Arch of Constantine, the figures are even more squat, frontally oriented, similar to one another, and there is a clear lack of naturalism. The message is meant to be understood without hesitation: Constantine is in power.

The Emperor Constantine, called Constantine the Great, was significant for several reasons. These include his political transformation of the Roman Empire, his support for Christianity, and his founding of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul). Constantine’s status as an agent of change also extended into the realms of art and architecture. The Triumphal Arch of Constantine in Rome is not only a superb example of the ideological and stylistic changes Constantine’s reign brought to art, but also demonstrates the emperor’s careful adherence to traditional forms of Roman Imperial art and architecture.

The Arch of Constantine is located along the Via Triumphalis in Rome, and it is situated between the Flavian Amphitheater (better known as the Colosseum) and the Temple of Venus and Roma. This location was significant, as the arch was a highly visible example of connective architecture that linked the area of the Forum Romanum (Roman Forum) to the major entertainment and public bathing complexes of central Rome. Three portals punctuate the exceptional width of the arch, each flanked by partially engaged Corinthian columns. The central opening is approximately 12 meters high, above which are identical inscribed marble panels, one on each side, that read:

To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantinus, the Greatest, pious, fortunate, the Senate and people of Rome, by inspiration of divinity and his own great mind with his righteous arms on both the tyrant and his faction in one instant in rightful battle he avenged the republic, dedicated this arch as a memorial to his military victory.

Beginning in the late 3rd century, the Roman Empire was ruled by four co-emperors (two senior emperors and two junior emperors), in an effort to bring political stability after the turbulent 3rd century. But in 312 C.E., Constantine took control over the Western Roman Empire by defeating his co-emperor Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (and soon after became the sole ruler of the empire). The inscription on the arch refers to Maxentius as the tyrant and portrays Constantine as the rightful ruler of the Western Empire. Curiously, the inscription also attributes the victory to Constantine’s “great mind” and the inspiration of a singular divinity. The mention of divine inspiration has been interpreted by some scholars as a coded reference to Constantine’s developing interest in Christian monotheism.

Perhaps the most striking feature of the Arch is its eclectic and stylistically varied relief sculptures. Some aspects of the sculpture are quite standard, like the Victory (or Nike) figures that occupy the spandrels above the central archway, or the typical architectural moldings found in most imperial Roman public and religious architecture. Other sculpted elements, however, show a multiplicity of styles. In fact, most scholars accept that many of the sculptures of the arch were spolia taken from older monuments dating to the 2nd century C.E. Although there is some scholarly disagreement on the origins of the sculptures, their imperial style corresponds to those of the reigns of Trajan (ruled 98-117 C.E.—the figures surmounting the decorative columns), Hadrian (ruled 117-138 C.E.—the middle register roundels), and Marcus Aurelius (ruled 161-180 C.E.—the large panel reliefs on the top registers). Most of the reliefs feature the emperors participating in codified activities that demonstrate the ruler’s authority and piety by addressing troops, defeating enemies, distributing largesse, and offering sacrifices.

Some sculptural elements of the structure also date to Constantine’s reign, most notably the frieze which is located immediately above the portals. These relief sculptures are of a drastically different style and narrative content when compared with the spoliated (older, borrowed) sections; Constantine’s relief sculptures feature squat and blocky figures that are more abstract than they are naturalistic.

The Constantinian reliefs also depict historical, rather than general events related to Constantine, including his rise to power and victory over Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge. There is also a scene of Constantine distributing largesse (funds) to the public—recalling the scenes of emperors from the earlier sculptures.

Regarding style, the relief figures from Constantine’s age still seem like outliers. Yet in comparison to the idealized naturalism of the earlier sculptural elements, the thick, bold outlines of the Constantinian figures render them remarkably legible to passersby. While the Constantinian figures lack natural aesthetics, their clarity of form ensured that they were informative and communicated Constantine’s official (and celebrated) history to viewers of his own time.

If, indeed, the spoliated material from the arch can be traced to the reigns of Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius, then it situates Constantine as one worthy of the same level of reverence as those emperors—all of whom earned deserved levels of acclaim. This was vitally important to Constantine, who had himself essentially bypassed lawful succession and usurped power from others. Moreover, Constantine encouraged major social changes in Rome, such as decriminalizing Christianity. Any religious change was a threat to the ruling and political classes of Rome. By aligning himself with well-regarded emperors of Rome’s 2nd-century C.E. golden age, Constantine was signaling that he intended to model his rule after earlier, successful leaders.

The Arch of Constantine

When Constantine and Maxentius clashed at the Milvian Bridge, Maxentius was in the middle of building a grand basilica. It was eventually renamed the Basilica Nova and was located near the Roman Forum.

When Constantine took over and completed the grand building, it was 300 feet long, 215 feet wide, and stood 115 feet tall down the nave. Concrete walls 15 feet thick supported the basilica’s massive scale and expansive vaults. It was lavishly decorated with marble veneer and stucco. The southern end of the basilica was flanked by a porch, with an apse at the northern end.

Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine

The apse of the Basilica Nova was the location of the Colossus of Constantine. This colossus was built from many parts. The head, arms, hands, legs, and feet were carved from marble, while the body was built with a brick core and wooden framework and then gilded.

Only parts of the Colossus remain, including the head that is over eight feet tall and 6.5 feet long. It shows a portrait of an individual with clearly defined features: a hooked nose, prominent jaw, and large eyes that look upwards. Constantine’s portrait combines naturalism in his nose, mouth, and chin with a growing sense of abstraction in his eyes and geometric hairstyle.

He also held an orb and, possibly, a scepter, and one hand points upwards towards the heavens. Both the immensity of the scale and his depiction as Jupiter (seated, heroic, and semi-nude) inspire a feeling of awe and overwhelming power and authority.

The Colossus of Constantine

Following Constantine’s founding of a New Rome at Constantinople, the prominence and importance of the city of Rome diminished. The empire was then divided into east and west. The more prosperous eastern half of the empire continued to thrive, mainly due to its connection to important trade routes, while the western half of the empire fell apart.

While Byzantium controlled Italy and the city Rome at times over the next several centuries, for the most part the Western Roman Empire, due to being less urban and less prosperous, was difficult to protect. Indeed, the city of Rome was sacked multiple times by invading armies, including the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, over the next century.

The multiple sackings of Rome resulted in the raiding of the marble, facades, décor, and columns from the monuments and buildings of the city. Parts of ancient Rome, especially the Republican Forum, returned once again to the cow pastures that they originally were at the time of the city’s founding, as floods from the Tiber washed them over in debris and sediment.

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century B.C.E., known for his multi-volume work entitled De architectura. He originated the idea that all buildings should have three attributes: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas ("strength", "utility", and "beauty"). These principles were later widely adopted in Roman architecture. His discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci. The entire text can be found online at the Perseus Digital Library. ↵

- a mythical creature that lived in Ceryneia, Greece and took the form of an enormous female deer, larger than a bull, with golden antlers like a stag, hooves of bronze or brass, and a "dappled hide", that "excelled in swiftness of foot", and snorted fire. ↵

- “Classical”, or “Classicizing,” when used in reference to Roman art refers broadly to the influences of Greek art from the Classical and Hellenistic periods (480-31 B.C.E.). Classicizing elements include the smooth lines, elegant drapery, idealized nude bodies, highly naturalistic forms and balanced proportions that the Greeks had perfected over centuries of practice. ↵

an extensive and elaborate burial place of an ancient city.

the inner chamber of an ancient Greek or Roman temple in classical antiquity

the piecing together of one or more materials to create a 3D piece of art.

the removal of pieces of material through carving, cutting, sanding, and other techniques to acquire the desired form.

a low-density, lightweight volcanic rock

a curved symmetrical structure spanning an opening and typically supporting the weight of a bridge, roof, or wall above it

a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof.

the elevation of someone to divine status; deification

the reuse of building stone or decorative sculpture on a new monument

The basilica is a form of building that dates to the Roman Republic and was a common Roman building that functioned as a multipurpose space for law courts, senate meetings, and business transactions. The form was appropriated for Christian worship and most churches, even today, still maintain this basic shape.