4 The Classical World: Greece and the Ancient Aegean

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify key works of art and differentiate between the arts of the Ancient Aegean.

- Describe the distinctive ideals of human representation and architectural design that emerged during the Greek periods.

- Trace the developing features that characterize Greek art and architecture.

Looking Forward

Ancient Greece can feel strangely familiar. From the exploits of Achilles (a hero in the ancient epic poem by Homer, The Illiad), about the Trojan War and Odysseus (the hero in Homer’s The Odyssey), to the treatises of Aristotle, from the exacting measurements of the Parthenon to the rhythmic chaos of the Laocoön, ancient Greek culture has shaped our world. Thanks largely to notable archaeological sites, well-known literary sources, and the impact of Hollywood (Clash of the Titans, for example), this civilization is embedded in our collective consciousness—prompting visions of epic battles, erudite philosophers, gleaming white temples, and limbless nudes (we now know the sculptures—even the ones that decorated temples like the Parthenon—were brightly painted, and, of course, the fact that the figures are often missing limbs is the result of the ravages of time).

In Full Color, Ancient Sculpture Reimagined

Dispersed around the Mediterranean and divided into self-governing units called poleis or city-states, the ancient Greeks were united by a shared language, religion, and culture. Strengthening these bonds further were the so-called “Panhellenic” sanctuaries and festivals that embraced “all Greeks” and encouraged interaction, competition, and exchange (for example the Olympics, which were held at the Panhellenic sanctuary at Olympia). Although popular modern understanding of the ancient Greek world is based on the classical art of fifth century B.C.E. Athens, it is important to recognize that Greek civilization was vast and did not develop overnight.

The Bronze Age Aegean (c. 3200 – 1100 B.C.E.)

During the Bronze Age, a number of cultures flourished on the islands of the Cyclades, in Crete and on the Greek mainland. They were mainly farmers, but trade across the sea, particularly in raw materials such as obsidian (volcanic glass) and metals, was growing. Aegean art covers two major pre-Greek civilizations: the Minoans and the Mycenaeans. Both were influenced by earlier civilizations (their writing systems, for instance, are thought to be adaptations of Egyptian and Mesopotamian systems), and the Mycenaeans, who eventually colonized Minoan Crete, were the immediate forerunners of the ancient Greeks.

The Mycenaean period of the later Greek Bronze Age was viewed by the Greeks as the “age of heroes” and perhaps provides the historical background to many of the stories told in later Greek mythology, including Homer’s epics. Objects and artworks from this time are found throughout mainland Greece and the Greek islands. Distinctive Mycenaean pottery was distributed widely across the eastern Mediterranean, and shows the beginnings of Greek mythology being used to decorate works of art.

Minoan Crete

The Minoan civilization (c. 3500–1050 B.C.E.) on the island of Crete was an agrarian society whose livelihood depended on farming, fishing, and sea trade. Archaeological evidence dates the arrival of the earliest inhabitants of Crete in approximately 6000 B.C.E. Over the next four thousand years the inhabitants developed a civilization based on agriculture, trade, and production.

The ancient sites on the island of Crete were first excavated in the early 1900s by the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. While excavating the site of Knossos, he discovered the ruins of a palace whose labyrinthine-like structure reminded him of the mythical labyrinth of the Minotaur. Evans named the civilization and its people after the legendary King Minos, keeper of the Minotaur.

Bad History

In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth was an elaborate, confusing structure designed and built by the legendary artificer Daedalus for King Minos of Crete at Knossos. Its function was to hold the Minotaur, the monster eventually killed by the hero Theseus. Daedalus had so cunningly made the Labyrinth that he could barely escape it after he built it.

When Sir Arthur Evans first excavated at Knossos, not only did he mistakenly believe he was looking at the legendary labyrinth of King Minos, but he also thought he was excavating a palace. However, the small rooms and archives excavated at the site have led researchers to believe that these “palaces” were actually administrative centers. Even so, the name became ingrained into the academic lexicon of Minoan research, and these large, communal buildings across Crete are referred to as palaces.

There are a number of issues regarding the archaeological practices and the constructed historiography of early Minoan and Mycenaean archaeologists. For more information, take a look at some of the formal questions that arise when we assess the reconstructions of Arthur Evans at Knossos.

Our knowledge of Early Minoan Crete comes primarily from burials and a number of excavated settlement sites. Around 1900 B.C.E., during the Middle Minoan period, Minoan civilization on Crete reached its apogee with the establishment of centers, called palaces, that concentrated political and economic power, as well as artistic activity, and may have served as centers for the redistribution of agricultural commodities.

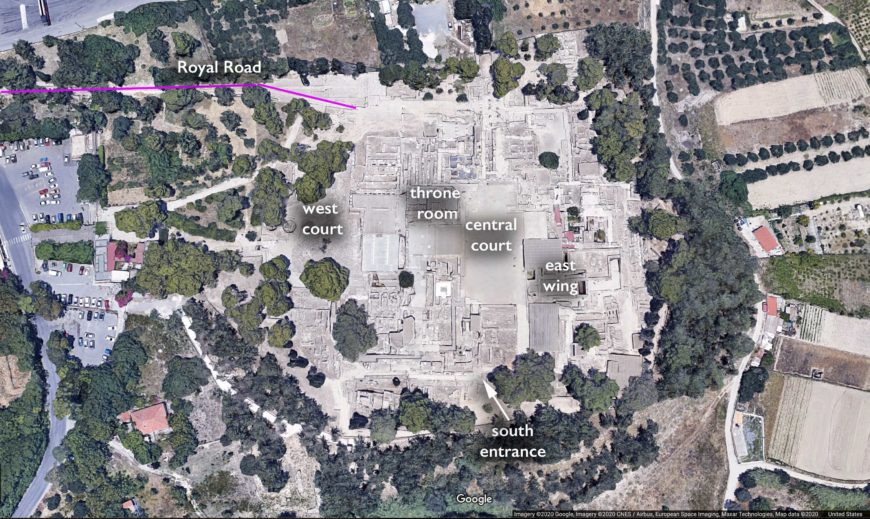

The complex at Knossos provides an example of the monumental architecture built by the Minoans. In general, there were no defensive walls, although a network of watchtowers punctuating key roads on the island has been identified. The most prominent feature on the plan is the palace’s large, central courtyard, which may have been the location of large ritual events, including bull leaping.

Minoan palaces are distinguished by their arrangement around a paved central court and sophisticated masonry. Several small tripartite shrines surround the courtyard. The numerous corridors and rooms of the palace center create multiple areas for storage, meeting rooms, shrines, and workshops. The absence of a central room and living chambers suggest the absence of a king and, instead, the presence and rule of a strong, centralized government.

The palaces also have multiple entrances that often take long paths to reach the central courtyard or a set of rooms. There are no fortification walls, although the multitude of rooms creates a protective, continuous façade. While this provides some level of fortification, it also provides structural stability for earthquakes. Even without a wall, the rocky and mountainous landscape of Crete and its location as an island creates a high level of natural protection.

The walls and floors of the palaces were often painted, and colorful frescoes depicted rituals or scenes of nature. Because the Minoan alphabet, known as Linear A, has yet to be deciphered, scholars must rely on the culture’s visual art to provide insights into Minoan life. The frescoes discovered in locations such as Knossos and Akrotiri inform us of the plant and animal life of the islands of Crete and Thera (Santorini), the common styles of clothing, and the activities the people practiced. For example, men wore kilts and loincloths. Women wore short-sleeve dresses with flounced skirts whose bodices were open to the navel, allowing their breasts to be exposed.

Minoan Fresco Painting

Buon fresco (“true’ fresco) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid (“wet”) lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting becomes an integral part of the wall.

In the Minoan variation, the stone walls are first covered with a mixture of mud and straw, then thinly coated with lime plaster, and lastly with layers of fine plaster.

The Minoans had a distinct painting style with shapes formed by curvilinear lines that add a feeling of liveliness to the paintings. The Minoan color palette is based in earth tones of white, brown, red, and yellow. Black and vivid blue are also used. These color combinations create vivid and rich decoration.

Fragments of frescoes found at Knossos also provide us with glimpses into Minoan culture and rituals.What we see is a freeze-frame of a very fast-moving scene. The central image of the fresco as reconstructed is a bull charging with such force that its front and back legs are in midair. In front of the bull is a person grasping its horns, seemingly about to vault over it. The next person is in mid-vault, upside down, over the back of the bull, and the final person is facing the rear of the animal, arms out, apparently just having dismounted— “sticking the landing,” as they say in gymnastics. Unlike the twisted perspective seen in Egyptian or Ancient Near Eastern works of art, these figures are shown in full profile, an element that adds to the air of liveliness.

The people on either side of the bull, as reconstructed, bear markers of both male and female gender: they are painted white, which indicates a female figure according to ancient Egyptian gender-color conventions, which we know the Minoans also used. But both characters wear merely a loincloth, which is male dress. The hairstyle (curls at the top with locks falling down the back) is not uncommon in representations of both youthful males and females. Many interpretations of this gender crossing are possible, but there is little evidence to support one over another, unfortunately. At the very least, we can say that the representation of gender in the Late Aegean Bronze Age was fluid.

The most interesting question about the bull leaping paintings from Knossos is what they might mean. The figures are participating in an activity known as bull-leaping. Bull sports—including leaping over them, fighting them, running from them, or riding them—have been practiced all around the globe for millennia. We cannot understand the whole bull-leaping cycle in detail as it is so fragmentary, but we know that it covered a lot of wall space, and a considerable amount of resources must have been expended to create it. We may never know the exact meaning of these paintings, but they continue to resonate with us today—not only because of their beauty and dynamism, but because they represent an activity that is still an important part of many cultures around the world.

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean is the term applied to the art and culture of Greece from ca. 1600 to 1100 B.C.E. The name derives from the site of Mycenae in the Peloponnesus, where once stood a great Mycenaean fortified palace. Mycenae is celebrated by Homer as the seat of King Agamemnon, who led the Greeks in the Trojan War.

More Bad History…

Like the Minoan sites, Mycenae was excavated by a Western European archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, in the late nineteenth century. He was looking for evidence of the Homeric epics (the Iliad and the Odyssey), especially the legendary city of Troy. He claimed that Mycenae was the mythical and historical home of King Agamemnon, which is why one of the objects found there is still commonly referred to as the Mask of Agamemnon. Again, we are confronted here with the problem of verifying such claims.

In the latter half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, the authenticity of the mask has been formally questioned. Proponents of the fraud argument center their case on Schliemann’s reputation for fraudulently littering archaeological digs with artifacts from elsewhere. The resourceful Schliemann, they assert, could have had the mask manufactured on the general model of the other Mycenaean masks and found an opportunity to place it in the excavation.

A second critique is based on style. The Mask of Agamemnon differs from three of the other masks in a number of ways: it is three-dimensional rather than flat, one of the facial hairs is cut out, rather than engraved, the ears are cut out, the eyes are depicted as both open and shut, with open eyelids, but a line of closed eyelids across the center, the face alone of all the depictions of faces in Mycenaean art has a full pointed beard with handlebar mustache, the mouth is well-defined (compared to the flat masks), the brows are formed to two arches rather than one.

Modern archaeological research suggests that the mask is genuine but pre-dates the period of the Trojan War by 300–400 years. Others date the contents of the find even earlier, to approximately 2500 BC.

During the Mycenaean period, the Greek mainland enjoyed an era of prosperity centered in such strongholds as Mycenae, Tiryns, Thebes, and Athens. Contact with Minoan Crete played a decisive role in the shaping and development of Mycenaean culture, especially in the arts. Wide-ranging commerce circulated Mycenaean goods throughout the Mediterranean world from Spain and the Levant. The evidence consists primarily of vases, but their contents (oil, wine, and other commodities) were probably the chief objects of trade.

Despite this age of prosperity, the Greek mainland was prone to military conflict. As a result, Mycenaeans were fierce warriors and great engineers who designed and built remarkable cities like Mycenae in the form of a citadel. Standing in stark contrast to the mercantile city Knossos, the Mycenaeans populated Greece with citadels on high, rocky outcroppings that provided natural fortification and overlooked the plains used for farming and raising livestock.

The walls of Mycenaean citadel sites were often built with ashlar and massive stone blocks. The blocks were considered too large to be moved by humans and were believed by ancient Greeks to have been erected by the Cyclopes—one-eyed giants. Due to this ancient belief, the use of large, roughly cut, ashlar blocks in building is referred to as Cyclopean masonry. The thick Cyclopean walls reflect a need for protection and self-defense since these walls often encircled the citadel site and the acropolis on which the site was located.

The Mycenaeans also relied on new techniques of building to create supportive archways and vaults. A typical post-and-lintel is not strong enough to support the heavy structures built above it, so a corbeled arch was employed over doorways to relieve the weight on the lintel.

Architectural Support Systems

In architecture, post and lintel (also called a trabeated system) is a building system where strong horizontal elements are held up by strong vertical elements with large spaces between them. This is usually used to hold up a roof, creating a largely open space beneath. The horizontal elements are called by a variety of names including lintel, header, architrave or beam, and the supporting vertical elements may be called columns, pillars, or posts. The trabeated system is a fundamental principle of Neolithic, ancient Greek, and ancient Egyptian architecture.

A corbel arch is an arch-like construction method that uses the architectural technique of corbeling to span a space in a structure. A corbel arch is constructed by offsetting successive horizontal courses of stone (or brick) beginning at the springline of the walls (the point at which the walls break off from verticality to form an arc toward the apex at the archway’s center) so that they project towards the archway’s center from each supporting side, until the courses meet at the apex of the archway (often, the last gap is bridged with a flat stone).

Although an improvement in load-bearing efficiency over the post and lintel design, corbeled arches are not entirely self-supporting structures, and the corbeled arch is sometimes termed a “false” arch for this reason.

The citadel site of Mycenae was the center of Mycenaean culture. The main approach to the citadel is through the Lion Gate, a cyclopean-walled entrance way. The gate is 20 feet wide, which is large enough for citizens and wagons to pass through, but its size and the walls on either side create a tunneling effect that makes it difficult for an invading army to penetrate.

The gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel. The Lion Gate received its name from its decorated relieving triangle of lions one either side of a single column. This composition of lions or another feline animal flanking a single object is known as a heraldic composition and represents the cultural influences from the Ancient Near East.

Lion Gate, Mycenae

Inside the walls are various rooms for administration and storage along with palace quarters, living spaces, and temples. The site’s megaron sits on the highest part of the acropolis and is reached through a large staircase. A large grave site, known as Grave Circle A, is also built within the walls.

Repoussé death masks, created from thin sheets of gold through a careful method of metalworking to create a low relief, were found in many of the tombs. These objects are fragile, carefully crafted, and laid over the face of the dead. The most famous of the death masks is the Mask of Agamemnon, under the assumption that this was the burial site of the Homeric king. The mask depicts a man with a triangular face, bushy eyebrows, a narrow nose, pursed lips, a mustache, and stylized ears.

Mask of Agamemnon

The Dark Ages to the Archaic Period (c. 1100 – 480 B.C.E.)

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean citadels of the late Bronze Age, the Greek mainland entered a “Dark Age” that lasted from c. 1100 until c. 800 B.C.E. Not only did the complex socio-cultural system of the Mycenaeans disappear, but so did its numerous achievements (i.e., metalworking, large-scale construction, writing). By c. 800 B.C.E., however, Greece experienced a cultural revival of its historical past that would lay the foundations for a dramatic transformation that would eventually lead to the establishment of the primary Greek institutions of the Classical Period.

The Geometric Period

During the Geometric period (c. 800 to 700 B.C.E.), the Greek city-state (polis) was formed, the Greek alphabet was developed, and new opportunities for trade and colonization were realized in cities founded along the coast of Asia Minor, in southern Italy, and in Sicily. With the development of the Greek city-states came the construction of large temples and sanctuaries dedicated to patron deities, which signaled the rise of state religion. A newly emerging aristocracy distinguished itself with material wealth and through references to the Homeric past.

Unfortunately, limited archaeological evidence remains that describes everyday life during this period. Monumental kraters, originally used as grave markers, depict funerary rituals and heroic warriors. The presence of fine metalwork attests to prosperity and trade. In the earlier Geometric period, these objects, weapons, fibulae, and jewelry are found in graves—most likely relating to the status of the deceased. By the late eighth century B.C., however, the majority of metal objects are small bronze figurines—votive offerings associated with sanctuaries.

Votive offerings of bronze and terracotta, and painted scenes on monumental vessels attest to a renewed interest in figural imagery that focuses on funerary rituals and the heroic world of aristocratic warriors and their equipment. The armed warrior, the chariot, and the horse are the most familiar symbols of the Geometric period. Iconographically, Geometric images are difficult to interpret due to the lack of inscriptions and the scarcity of identifying attributes. There can be little doubt, however, that many of the principal characters and stories of Greek mythology already existed, and that they simply had not yet received explicit visual form.

The Dipylon Master, an unknown painter whose hand is recognized on many different vessels, displays the great expertise required for decorating these funerary markers. The vessels were first thrown a wheel, an important technological development at the time, before painting began. Both the Diplyon Krater and Dipylon Amphora demonstrate the main characteristics of painting during this time. For one, the entire vessel is decorated in a style known as horror vacui, a style in which the entire surface of the medium is filled with imagery. A decorative meander is on the lip of the krater and on many registers of the amphora. This geometric motif is constructed from a single, continuous line in a repeated shape or motif.

On the Dipylon Krater, now located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, clearly divided registers of decoration alternate between different abstract geometric designs, including the meander pattern seen in the upper lip of the pot. The belly of the krater is decorated with two larger registers that are separated by geometric patterns and filled with a stylized representation of a funeral procession. The upper register reveals the deceased individual, laid out rigidly across a funerary bier, and to either side appear abstract female forms, whose crossed arms overhead are meant to signal their mourning. The lower register reveals a procession of soldiers with their horses, presenting additional examples of the tendency toward abstracted figures. The soldiers, for example, appear as if they are shields with limbs, while the chariot horses are melded into one horse-like shape with a multitude of legs.

The Orientalizing Period

The Orientalizing Period (700-600 B.C.E.), followed the Geometric period and was distinguished by international influences—from the Ancient Near East and Asia Minor—each of which contributed a distinctive Eastern style to Greek art. The close contact between cultures developed from increasing trade and even colonization. Motifs, creatures, and styles were borrowed from other cultures by the Greeks, who transformed them into a unique Greek–Eastern mix of style and motifs. Alongside Near Eastern motifs and animal processions, craftsmen produced more nuanced figural forms and intelligible illustrations.

During the Orientalizing period, the Corinthians developed the technique of black figure painting, which quickly spread to Athens, and was futher exported throughout Greece. Black figure pottery was carefully constructed and fired three different times to produce the unique red and black colors on each vase. To produce the characteristic red and black colors found on vases, Greek craftsmen used liquid clay as paint (known as a “slip”) and perfected a complicated three-stage firing process. Not only did the pots have to be stacked in the kiln in a specific manner, but the conditions inside had to be precise. First, the temperature was stoked to about 800°C and vents allowed for an oxidizing environment. At this point, the entire vase turned red in color. Next, by sealing the vents (removing the oxygen) and increasing temperature to around 900-950°C, everything turned black and the areas painted with the slip vitrified (transformed into a glassy substance). Finally, in the last stage, the vents were reopened to return oxygen to the inside of the kiln. At this point, the unpainted zones of the vessel became red again while the vitrified slip (the painted areas) retained a glossy black hue. Through the removal of oxygen and its reintroduction into the kiln and, simultaneously, the increase and decrease in temperature, the slip transformed into a glossy black color unpainted portions of the vase would remain the original red-orange color of the pot, and the full effect of this style of painting would not have been seen until after the vase emerged from its firings in the kiln.

Sculpture produced during the Orientalizing period shares stylistic attributes with sculpture produced in the Near East. Male and female sculptures produced during this time share interesting similarities, but also bear differences that inform the viewer about society’s expectations of men and women.

There are no inscriptions on sculpture before the appearance of the bronze Mantiklos Apollo (early seventh century B.C.E.) found in Thebes. The figure, named for the individual who left it as an offering, is that of a standing man with a rigid and somewhat Daedalic form.

His legs bear the inscription, “Mantiklos offered me as a tithe to Apollo of the silver bow; do you, Phoibos [Apollo], give some pleasing favor in return.” The inscription is a declaration of the statuette to Apollo, followed by a request for favors in return.

Apart from the novelty of recording its own purpose, this sculpture adapts the formulae of later Orientalized sculptures, as seen in the shorter more triangular face and slightly advancing left leg.

A small limestone statue of a kore, known as the Lady of Auxerre (650–625 BCE), from Crete demonstrates the style of early Greek figural sculptures known as Daedalic sculpture, named for the mythical creator of King Minos’s labyrinth, Daedalus.

The Lady of Auxerre is stocky and plank-like. Her waist is narrow and cinched, like the waists seen in Minoan art. She is disproportionate, with long rigid legs and a short torso. A dress encompasses nearly her entire body—it tethers her legs together and restricts her potential for movement.

Her head is distinguished with large facial features, a low brow, and stylized hair that appears to be braided and falls down in rigid rows divided by horizontal bands. This style recalls a Near Eastern use of patterns to depict texture and decoration.

Her face and hair are reminiscent of the Geometric period. The face forms an inverted triangle wedged between the triangles formed be the hair that frames her face. Traces of paint tell us that this statue would have originally be painted with black hair and a dress of red and blue with a yellow belt.

Lady of Auxerre

Despite the separation of several decades and over 200 miles, the Mantiklos Apollo and the Lady of Auxerre share interesting similarities, including their long-plaited hair, cinched waist, stylized smile, and hand raised to the chest—all of which recall ancient Egyptian sculpture. Although the right arm of the Mantiklos Apollo is missing, the position of its shoulder implies a possible position similar to that of the left arm of the Lady of Auxerre, straight at its side.

However, we can already see striking differences that will remain the standard in Greek art for centuries. The male body, as a public entity entitled to citizenship, is depicted nude and free to move. This freedom of movement is seen not only in the legs of the Apollo figure but also in the separation of his hand from his chest.

On the other hand, the female body, as a private entity without individual rights, is clothed and denied movement. While the Mantiklos Apollo holds his hand parallel to his chest, the Lady of Auxerre places her hand directly on hers, maintaining the closed form expected of a respectable woman.

The Archaic Period

A striking change appears in Greek art of the seventh century B.C.E., the beginning of the Archaic period. The abstract geometric patterning that was dominant between about 1050 and 700 B.C. is supplanted by a more naturalistic style reflecting significant influence from Egypt.

Sculpture in the Archaic Period developed rapidly from its early influences, becoming more natural and showing a developing understanding of the body, specifically the musculature and the skin. Visually, the period is known for large-scale marble kouros (male youth; plural, kouroi) and kore (female youth; plural, korai) sculptures.

Kouroi statues, depicting idealized, nude male youths, were first seen during this period. Carved in the round, often from marble, kouroi are thought to be associated with Apollo; many were found at his shrines and some even depict him. Emulating the statues of Egyptian pharaohs, the figure strides forward on flat feet, arms held stiffly at its side with fists clenched. However, there are some importance differences: kouroi are nude, mostly without identifying attributes and are free-standing.

Early kouroi figures share similarities with Geometric and Orientalizing sculpture, despite their larger scale. For instance, their hair is stylized and patterned, either held back with a headband or under a cap. The New York Kouros strikes a rigid stance, and his facial features are blank and expressionless. The body is slightly molded, and the musculature is reliant on incised lines. As kouroi figures developed, they began to lose their Egyptian rigidity and became increasingly naturalistic. The kouros figure of Kroisos (also known as the Anavysos Kouros), an Athenian youth killed in battle, still depicts a young man with an idealized body. This time though, the body’s form shows realistic modeling. The muscles of the legs, abdomen, chest and arms appear to actually exist and seem to function and work together. Kroisos’ hair, while still stylized, falls naturally over his neck and onto his back, unlike that of the New York Kouros, which falls down stiffly and in a single sheet. The reddish appearance of his hair reminds the viewer that these sculptures were once painted. Kroisos’ face also appears more naturalistic when compared to the earlier New York Kouros. His cheeks are round and his chin bulbous; however, his smile seems out of place. This is typical of this period and is known as the Archaic smile. It appears to have been added to infuse the sculpture with a sense of being alive and to add a sense of realism.

New York Kouros

Korai (singular, kore), on the other hand, was never nude. Whereas kouroi depict athletic, nude young men, the female korai are fully clothed, in the idealized image of decorous women. Unlike men—whose bodies were perceived as public, belonging to the state—women’s bodies were deemed private and belonged to their fathers (if unmarried) or husbands. However, they also have Archaic smiles, with arms either at their sides or with an arm extended, holding an offering. The figures are stiff and retain more block-like characteristics than their male counterparts. Their hair is also stylized, depicted in long strands or braids that cascade down the back or over the shoulder.

The Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE) depicts a young woman wearing a peplos, a heavy wool garment that drapes over the whole body, obscuring most of it. A slight indentation between the legs, a division between her torso and legs, and the protrusion of her breasts merely hint at the form of the body underneath. Remnants of paint on her dress tell us that it was painted yellow with details in blue and red that may have included images of animals. The presence of animals on her dress may indicate that she is the image of a goddess, perhaps Artemis, but she may also just be a nameless maiden.

Peplos Kore from the Acropolis

A Word of Warning…

As mentioned in the discussion of the reconstructions at the Minoan center of Knossos, remember to take these as loose reconstructions and not absolute fact. There are several predominant variations:

The Classical Style (480 – 323 B.C.E)

Though experimentation in realistic movement began before the end of the Archaic Period, Greek artists of the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E. attained a manner of representation that conveys a vitality of life as well as a sense of permanence, clarity, and harmony. The “Early Classical Period” (480/479 – 450 B.C.E.) was a period of transition when some sculptural work displayed archaizing holdovers alongside the so-called “Severe Style.”

During the “High Classical Period” (450-400 B.C.E.), there was great artistic success: from the innovative structures on the Acropolis to Polykleitos’ visual and cerebral manifestation of idealization in his sculpture of a young man holding a spear, the Doryphoros or “Canon”. Concurrently, however, Athens, Sparta, and their mutual allies were embroiled in the Peloponnesian War, a bitter conflict that lasted for several decades and ended in 404 B.C.E.

The Early Classical Period

A slightly smaller-than-life statue known as the Kritios Boy was dedicated to Athena by an athlete and found in the Perserchutt of the Athenian Acropolis. As can be seen in the Kritios Boy, c. 480 B.C.E., the “Severe Style” features realistic anatomy, serious expressions, pouty lips, and thick eyelids.

The marble statue is a prime example of the Early Classical sculptural style and demonstrates the shift away from the stiff style seen in Archaic kouroi. The torso depicts an understanding of the body and plasticity of the muscles and skin that allows the statue to come to life.

Part of this illusion is created by a stance known as contrapposto. This describes a person with his or her weight shifted onto one leg, which creates a shift in the hips, chest, and shoulders to create a stance that is more dramatic and naturalistic than a stiff, frontal pose. This contrapposto position animates the figure through the relationship of tense and relaxed limbs.

However, the face of the Kritios Boy is expressionless, which contradicts the naturalism seen in his body. This is known as the Severe style. The blank expressions allow the sculpture to appear less naturalistic, which creates a screen between the art and the viewer. This differs from the use of the Archaic smile (now gone), which was added to sculpture to increase their naturalism. However, the now empty eye sockets once held inlaid stone to give the sculpture a lifelike appearance.

Kritios Biy

For painters, the development of perspective and multiple ground lines enriched compositions. While artists continued to produce black-figure paintings into the second century B.C.E., the technique became increasingly rare, overtaken around 520 B.C.E. by red-figure painting that developed in Athens.

The naturalism of the figures in Early Classical vase painting continued to increase, as the figures became less stocky and less linear. Both the figures and their drapery began to appear more plastic, and the scenes often depicted a single moment within a mythical story or event. Furthermore, vase painting began to be influenced by the changes occurring in both sculpture and the large-scale painting of walls and panels.

The Niobid Painter’s red-figure krater of Artemis and Apollo slaying the children of Niobe, from 460 B.C.E., is believed to be a composition inspired by a panel painting. The side of the vessel depicting Artemis and Apollo relates to the myth of the twin god and goddess who slew Niobe’s fourteen children after she boasted that her ability to birth children exceeded Leto, the mother of Apollo and Artemis. This story alludes to ancient Greek admonitions against hubris, or extreme pride. The scene is one of the first vase painting scenes to show the figures on different ground lines. Apollo and Artemis stand in the center of the vessel as Niobe’s children fall to ground around them. One child has even fallen behind a rock in the landscape.

On the other side of the vase is an image of gods and heroes, with Herakles at the center. All the figures stand and sit on various ground lines. The figures on both sides are depicted from multiple angles, including three-quarter view, and a profile eye is used for the figures in profile, a first in Greek vase painting.

Attic Red-Figure: Niobid Painter, “Niobid Krater”

The High Classical Period

Despite continued military activity throughout the “Late Classical Period” (400-323 B.C.E.), artistic production and development continued apace.

Polykleitos was a Greek sculptor and art theorist during the early- to mid-fifth century B.C.E. most renowned for his treatise on the male nude, known as the Canon, which describes the ideal, aesthetic body based on mathematical proportions and Classical conventions such as contrapposto.

His Doryphoros, or Spear Bearer, is believed to be his representation of the Canon in sculpted form. The statue depicts a young, well-built soldier holding a spear in his left hand with a shield attached to his left wrist. Both military implements are now lost. The figure has a Severe-style face and a contrapposto stance. In another development away from the stiff and seemingly immobile Archaic style, the Doryphoros’ left heel is raised off the ground, implying an ability to walk.

This sculpture demonstrates how the use of contrapposto creates an S-shaped composition. The juxtaposition of a tension leg and tense arm and relaxed leg and relaxed arm, both across the body from each other, creates an S through the body.

The dynamic power of this composition shape places elements—in this case the figure’s limbs—in opposition to each other and emphasizes the tension this creates. The statue, as a visualization of Polykletios’ canon, also depicts the Greek sense of symmetria, the harmony of parts, seen here in the body’s proportions.

Bronze was a popular sculpting material for the Greeks, and it was used throughout their history. Composed of a metal alloy of copper and tin, it provides a strong and lightweight material for use in the ancient world, especially in the creation of weapons and art. However, because bronze is a valuable material, throughout history bronze sculptures were melted down to forge weapons and ammunition or to create new sculptures. The Greek bronzes that we have today mainly survived because of shipwrecks, which kept the material from being reused, and the sculptures have since been recovered from the sea and restored.

Much of our knowledge of Greek sculpture comes from Roman copies. The Romans were very fond of Greek art and collecting marble replicas of them was a sign of status, wealth, and intelligence in the Roman world. Roman copies worked in marble had a few differences from the original bronze. Struts were added to help buttress the weight of the marble as well as the hanging limbs that did not need support when the statue was originally made in the lighter and hollow bronze. The struts appeared either as rectangular blocks that connect an arm to the torso or as tree stumps against the leg, which supports the weight of the sculpture.

Polykleitos’ Doryphoros: ideal beauty in ancient Greece

In addition to a new figural aesthetic in the fourth century known for its longer torsos and limbs, and smaller heads, the first female nude was produced. Known as the Aphrodite of Knidos, c. 350 B.C.E., the sculpture pivots at the shoulders and hips into an S-Curve and stands with her right hand over her genitals in a pudica (or modest Venus) pose. Exhibited in a circular temple and visible from all sides, the Aphrodite of Knidos became one of the most celebrated sculptures in all of antiquity.

Capitoline Venus

During the Classical period, Greek architecture also underwent several significant changes. The architectural refinements perfected during the Late Classical period opened the doors of experimentation with how architecture could define space, an aspect that became the forefront of later Hellenistic architecture.

The Parthenon represents a culmination of style in Greek temple architecture. The optical refinements found in the Parthenon—the slight curve given to the whole building and the ideal placement of the metopes and triglyphs over the column capitals —represent the Greek desire to achieve a perfect and harmonious design known as symmetria.

While the artist Phidias was in charge of the overall plan of the Acropolis, the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates designed and oversaw the construction of the Parthenon (447–438 B.C.E.), the temple dedicated to Athena. The Parthenon is built completely from Pentalic marble, although parts of its foundations are limestone from a pre-480 B.C.E. temple that was never completed.

The design varies slightly from the basic temple ground plan. The temple is peripteral, and so is surrounded by a row of columns. In front of both the pronaos (porch) and opisthodomos is a single row of prostyle columns. The opisthodomos is large, accounting for the size of the treasury of the Delian League, which Pericles moved from Delos to the Parthenon. The pronaos is so small it is almost non-existent. Inside the naos is a two-story row of columns around the interior and set in front of the columns is the cult statue of Athena. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece.

The Parthenon’s elevation has been streamlined and shows a mix of Doric and Ionic elements[1]. The exterior Doric columns are more slender and their capitals are rigid and cone-like. The entablature also appears smaller and less weighty then earlier Doric temples. The exterior of the temple has a Doric frieze consisting of metopes and triglyphs.

Inside the temple are Ionic columns and an Ionic frieze that wraps around the exterior of the interior building. Finally, instead of the columns, the whole building has an entasis, a slight curve to compensate for the human eye. If the building was built perfectly at right angles and with straight eyes, the human eye would see the lines as curved. In order for the Parthenon to appear straight to the eye, Iktinos and Kallikrates added curvature to the building that the eye would interpret as straight.

The Parthenon

The Hellenistic Period and Beyond (323 – 31 B.C.E.)

Between 334 and 323 B.C.E., Alexander the Great and his armies conquered much of the known world, creating an empire that stretched from Greece and Asia Minor through Egypt and the Persian empire in the Near East to India. This unprecedented contact with cultures far and wide disseminated Greek culture and its arts, and exposed Greek artistic styles to a host of new exotic influences. The death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E. traditionally marks the beginning of the Hellenistic period. While some pieces intentionally mimicked the Classical style of the previous period, other artists were more interested in capturing motion and emotion. For example, on the Great Altar of Zeus from Pergamon expressions of agony and a confused mass of limbs convey a newfound interest in drama.

Upon the defeat of Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E., the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt and, simultaneously, the Hellenistic Period came to a close. With the Roman admiration of and predilection for Greek art and culture, however, Classical aesthetics and teachings continued to endure from antiquity to the modern era.

The Pergamon

Architecture in the Greek world during the Hellenistic period developed theatrical tendencies, as had Hellenistic sculpture. The conquests of Alexander the Great caused power to shift from the city-states of Greece to the ruling dynasties. Dynastic families patronized large complexes and dramatic urban plans within their cities. These urban plans often focused on the natural setting and were intended to enhance views and create dramatic civic, judicial, and market spaces that differed from the orthogonal plans of the houses that surrounded them.

The ancient city of Pergamon, now modern-day Bergama in Turkey, was the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon following the death of Alexander the Great and was ruled under the Attalid dynasty. The Acropolis of Pergamon is a prime example of Hellenistic architecture and the convergence of nature and architectural design to create dramatic and theatrical sites.

The acropolis was built into and on top a steep hill that commands great views of the surrounding countryside. Both the upper and lower portions of the acropolis were home to many important structures of urban life, including gymnasiums, agorae, baths, libraries, a theater, shrines, temples, and altars.

One feature found at Pergamon is the great Altar of Zeus (now housed in Berlin), commissioned in the first half of the second century B.C.E. during the reign of King Eumenes II to commemorate his victory over the Gauls, who were migrating into Asia Minor.

The altar is a U-shaped Ionic building built on a high platform with central steps leading to the top. It faced east, was located near the theater of Pergamon, and commanded an outstanding view of the region.

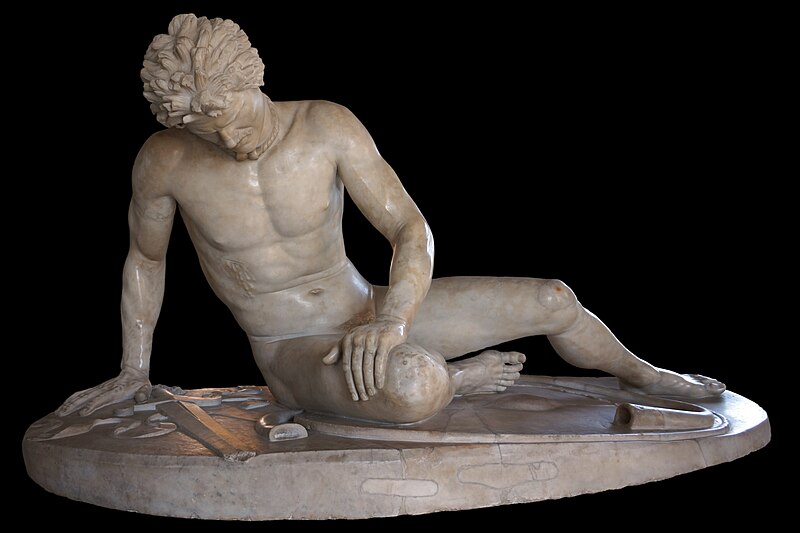

A group of statues depicting dying Gauls, the defeated enemies of the Attalids, were situated inside the Altar. The original set of statues is believed to have been cast in bronze by the court sculptor Epigonus in 230–220 B.C.E.. Now only marble Roman copies of the figures remain.

Like other Hellenistic sculptures, the figures are depicted with lifelike details and a high level of naturalism. They are also depicted in the common motif of barbarians. The men are nude and wear Celtic torcs; their hair is shaggy and disheveled. The figures are positioned in dramatic compositions and are shown dying heroically, which turns them into worthy adversaries, increasing the perception of power of the Attalid dynasty. To fully appreciate the statues, it is best to walk around them. Their pain, nobility, and death are evident from all angles.

One Gaul is depicted lying down, supporting himself over his shield and a discarded trumpet. He furrows his brow as he looks downward at his bleeding chest wound as he prepares himself for death. His muscles are large and strong, signifying his strength as a warrior and implying the strength of the one who struck him down.

Two other figures complete the group. One figure depicts a Gallic chief committing suicide after he has killed his own wife. Also known as the Ludovisi Gaul, this sculpture group displays another heroic and noble deed of the foes, for typically women and children of the defeated would be murdered to avoid them from being captured and sold as slaves by the victors. The chief holds his fallen wife by the arm as he plunges his sword into his chest, where blood is already exiting the wound.

The Dying Gaul and the Ludovisi Gaul

Nike of Samothrace

Hellenistic sculpture continues the trend of increasing naturalism seen in the stylistic development of Greek art. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favor of new themes, genres, drama, and pathos that were never explored by previous Greek artists. Furthermore, the Greek artists added a new level of naturalism to their figures by adding an elasticity to their form and expressions, both facial and physical. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction from their view—this is known as pathos.

One of the most iconic statues of the period, the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory, commemorates a naval victory. This Parian marble statue depicts Nike, now armless and headless, alighting onto the prow of the ship. The prow is visible beneath her feet, and the scene is filled with theatricality and naturalism as the statue reacts to her surroundings. Nike’s feet, legs, and body thrust forward in contradiction to her drapery and wings that stream backwards. Her clothing whips around her from the wind and her wings lift upwards. This depiction provides the impression that she has just landed and that this is the precise moment that she is settling onto the ship’s prow. In addition to the sculpting, the figure was most likely set within a fountain, creating a theatrical setting where both the imagery and the auditory effect of the fountain would create a striking image of action and triumph.

Nike of Samothrace

Laocoön and His Sons

Laocoön and His Sons, a Hellenistic marble sculpture group (attributed by the Roman historian Pliny the Elder to the sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus from the island of Rhodes) was created in the early first century CE to depict this scene from Virgil’s epic, The Aeneid.

Laocoön was a Trojan priest of Poseidon who warned the Trojans, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” when the Greeks left a large wooden horse at the gates of Troy. Athena or Poseidon (depending on the story’s version), upset by his vain warning to his people, sent two sea serpents to torture and kill the priest and his two sons.

Similar to other examples of Hellenistic sculpture, Laocoön and His Sons depicts a chiastic scene filled with drama, tension, and pathos. The figures writhe as they are caught in the coils of the serpents. The faces of the three men are filled with agony and toil, which is reflected in the tension and strain of their muscles. Laocoön stretches out in a long diagonal from his right arm to his left as he attempts to free himself.

His sons are also entangled by the serpents, and their faces react to their doom with confusion and despair. The carving and detail, the attention to the musculature of the body, and the deep drilling, seen in Laocoön’s hair and beard, are all characteristic elements of the Hellenistic style.

Laocoön and His Sons

- For more information on Greek Architecture and how it is classified, see an "Introduction to Ancient Greek Architecture" and "Greek Architectural Orders". ↵

of, concerning, or representing all people of Greek origin or ancestry.

consisting of three parts

a fortified palace complex surrounded by thick masonry walls and set on an easily defensible hill with sharp cliffs.

masonry made of large square-cut stones, typically used as a facing on walls of brick or stone.

a composition that is symmetrical on either side of a central figure.

reception area for the king

a metalworking technique in which a malleable metal is shaped by hammering from the reverse side to create a design in low relief

a jar or vase of classical antiquity having a large round body and a wide mouth and used for mixing wine and water

'fear of empty space': the filling of the entire surface of a space or an artwork with detail.

a style of pottery decoration in which figural and ornamental motifs were applied with a slip that turned black during firing, while the background was left the color of the clay

plural korai: a type of freestanding statue of a young woman—the female counterpart of the kouros, or standing youth—that appeared with the beginning of Greek monumental sculpture in about 660 BCE and remained to the end of the Archaic period in about 500 BCE.

a German term meaning "Persian debris" or "Persian rubble", refers to the bulk of architectural and votive sculptures that were damaged by the invading Persian army of Xerxes I on the Acropolis of Athens in 480 BC, in the Destruction of Athens during the Second Persian invasion of Greece.

a technique of vase painting that is essentially the reverse of black-figure vase painting. In the red-figure technique, the background of a vessel's surface is coated with a black slip. The decorative figures are left to stand out in reserve, that is, in the red-orange color of the base clay.

a body of principles, rules, standards, or norms.

supports that help buttress the weight of the marble as well as hanging limbs that did not need support when the statue was originally made in the lighter and hollow bronze.

having a single row of pillars on all sides in the style of the temples of ancient Greece

the rear room of an ancient Greek temple

of or involving right angles; at right angles.

a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century B.C.E. to 5th century C.E.)

a large rigid or stiff neck ring in metal, made either as a single piece or from strands twisted together.