6 The End of an Era: Late Antiquity and the Byzantine Empire

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain the origins and development of early Christian art.

- Characterize the early development of Byzantine art and architecture in the Eastern Roman Empire.

By 476, the Roman Empire had vanished from Western Europe; by 655, the Persian Empire had vanished from the Near East. It is only too easy to write about the Late Antique world as if it were merely a melancholy tale of ‘Decline and Fall’: of the end of the Roman Empire as viewed from the West; of the Persian, Sasanian Empire, as viewed from Iran. On the other hand, we are increasingly aware of the astounding new beginnings associated with the period: we go to it to discover why Europe became Christian and why the near east became Muslim…

Peter Brown, The World of Late Antiquity: AD 150-750. (New York: Norton, 1989), 7.

Late Antiquity: Christianity in the Roman Empire

Two important moments played a critical role in the development of early Christianity and its art in the Roman Empire:

- The decision of the Apostle Paul to spread Christianity beyond the Jewish communities of Palestine into the Greco-Roman world.

- When the Emperor Constantine accepted Christianity and became its patron at the beginning of the fourth century.

As implicit in the names of his Epistles, Paul spread Christianity to the Greek and Roman cities of the ancient Mediterranean world. In cities like Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, and Rome, Paul encountered the religious and cultural experience of the Greco-Roman world. This encounter played a major role in the formation of Christianity.

Christianity, in its first three centuries, was one of a large number of mystery religions that flourished in the Roman world. Religion in the Roman world was divided between the public, inclusive cults of civic religions and the secretive, exclusive mystery cults. The emphasis in the civic cults was on customary practices, especially sacrifices. Since the early history of the polis or city state in Greek culture, the public cults played an important role in defining civic identity.

As Christianity expanded and assimilated more people, Rome continued to use the public religious experience to define the identity of its citizens. The polytheism of the Romans allowed the assimilation of the gods of the people it had conquered. Thus, when the Emperor Hadrian created the Pantheon in the early second century, the building’s dedication to all the gods signified the Roman ambition of bringing cosmos or order to the gods, just as new and foreign societies were brought into political order through the spread of Roman imperial authority. The order of Roman authority on earth is a reflection of the divine cosmos.

For most adherents of mystery cults, there was no contradiction in participating in both the public cults and a mystery cult. The different religious experiences appealed to different aspects of life. In contrast to the civic identity, which was at the focus of the public cults, the mystery religions appealed to the participant’s concerns for personal salvation. The mystery cults focused on a central mystery that would only be known by those who had become initiated into the teachings of the cult.

There are characteristics that Christianity shares with numerous other mystery cults. For example, in early Christianity emphasis was placed on baptism, which marked the initiation of the convert into the mysteries of the faith. The Christian emphasis on the belief in salvation and an afterlife is also consistent with the other mystery cults. The monotheism of Christianity, though, was a crucial difference, and the refusal of the early Christians to participate in the civic cults due to their monotheistic beliefs lead to their persecution.

By the early years of Christianity (first century C.E.), Judaism had been legalized through a compromise with the Roman state over two centuries. Christians were initially identified with the Jewish religion by the Romans, but as they became more distinct, Christianity became a problem for Roman rulers. The oppression of Christians was only periodic until the middle of the first century. However, large-scale persecutions began in the year 64 when Nero blamed them for the Great Fire of Rome earlier that year. Because of their refusal to honor the Roman pantheon, which many believed brought misfortune upon the community, the local pagan populations put pressure on the imperial authorities to take action against their Christians neighbors. The last and most severe persecution organized by the imperial authorities was the Diocletianic Persecution from 303 to 311.

Christian Art before the Edict of Milan

It is difficult to know when distinctly Christian art began. Prior to 100, Christians may have been constrained by their position as a persecuted group from producing durable works of art. Since Christianity was largely a religion of the lower classes in this period, the lack of surviving art may reflect a lack of funds for patronage or a small number of followers. The Old Testament restrictions against the production of graven images might have also constrained Christians from producing art. Christians could have made or purchased art with pagan iconography but given it Christian meanings. If this happened, “Christian” art would not be immediately recognizable as such.

Jewish Christians, the Second Commandment, and Idolatry

The Second Commandment, as noted in the Old Testament, warns all followers of the Hebrew god Yahweh, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.”

In Judaism, and therefore Christianity, God chooses to reveal his identity, not as an idol or image, but by his words, by his actions in history, and by his working in and through humankind.

Although no single biblical passage contains a complete definition of idolatry, the subject is addressed in numerous passages, so that idolatry may be summarized as the worship of idols or images; the worship of polytheistic gods by use of idols or images; the worship of trees, rocks, animals, astronomical bodies, or another human being; and the use of idols in the worship of God.

The illusionary quality of classical art posed a significant problem for early Christian theologians. Early Christians saw themselves as the spiritual progeny of the Israelites and tried to comply with this commandment. Nevertheless, many early Christians were converted pagans who were accustomed to images in religious worship. The use of images in religious ritual was visually compelling and difficult to abandon.

The beginnings of an identifiable Christian art can be traced to the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. Considering the Old Testament prohibitions against graven images, it is important to consider why Christian art developed in the first place. The use of images will be a continuing issue in the history of Christianity. The best explanation for the emergence of Christian art in the early church is due to the important role images played in Greco-Roman culture.

As Christianity gained converts, these new Christians had been brought up on the value of images in their previous cultural experience and they wanted to continue this in their Christian experience. For example, there was a change in burial practices in the Roman world away from cremation to inhumation. Outside the city walls of Rome, adjacent to major roads, catacombs were dug into the ground to bury the dead. Wealthy Romans would also have sarcophagi or marble tombs carved for their burial. The Christian converts wanted the same things. Christian catacombs were dug frequently adjacent to non-Christian ones, and sarcophagi with Christian imagery were apparently popular with the richer Christians.

Catacomb of Priscilla and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

In a move of strategic syncretism, the Early Christians adapted Roman motifs and gave new meanings to what had been pagan symbols. During the persecution of Christians under the Roman Empire, Christian art was necessarily and deliberately furtive and ambiguous, using imagery that was shared with pagan culture but had a special meaning for Christians. Among the motifs adopted were the peacock, grapevines, and the “Good Shepherd.” Early Christians also developed their own iconography, such as with the symbol of the fish (Greek: ΙΧΘΥΣ [ichthus]), which served as the acrostic “Iēsous Christos Theou (h)uious sōtēr” meaning “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.”

One striking aspect of the Christian art of the third century is the absence of the imagery that will dominate later Christian art. We do not find in this early period images of the Nativity, Crucifixion, or Resurrection of Christ, for example. This absence of direct images of the life of Christ is best explained by the status of Christianity as a mystery religion. The story of the Crucifixion and Resurrection would be part of the secrets of the cult.

While not directly representing these central Christian images, the theme of death and resurrection was represented through a series of images, many of which were derived from the Old Testament that echoed the themes. For example, the story of Jonah—being swallowed by a great fish and then after spending three days and three nights in the belly of the beast is vomited out on dry ground—was seen by early Christians as an anticipation or prefiguration of the story of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Images of Jonah, along with those of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, the Three Hebrews in the Fiery Furnace, Moses Striking the Rock, among others, are widely popular in the Christian art of the third century, both in paintings and on sarcophagi.

Santa Maria Antiqua Sarcophagus

All of these can be seen to allegorically allude to the principal narratives of the life of Christ. The common subject of salvation echoes the major emphasis in the mystery religions on personal salvation. The appearance of these subjects frequently adjacent to each other in the catacombs and sarcophagi can be read as a visual litany: save me Lord as you have saved Jonah from the belly of the great fish, save me Lord as you have saved the Hebrews in the desert, save me Lord as you have saved Daniel in the Lion’s den, etc.

The image of “The Good Shepherd”, a beardless youth in pastoral scenes collecting sheep, was the most common of these images and was probably not understood as a portrait of the historical Jesus. These images bear some resemblance to depictions of kouroi figures in Greco-Roman art.

The almost total absence from Christian paintings during the persecution period of the cross, except in the disguised form of the anchor, is notable. The cross, symbolizing Jesus’s crucifixion, was not represented explicitly for several centuries, possibly because crucifixion was a punishment meted out to common criminals, but also because literary sources noted that it was a symbol recognized as specifically Christian, as the sign of the cross was made by Christians from the earliest days of the religion.

Christian Art after Constantine

By the beginning of the fourth century Christianity was a growing mystery religion in the cities of the Roman world. It was attracting converts from different social levels. Christian theology and art were enriched through the cultural interaction with the Greco-Roman world. But Christianity would be radically transformed through the actions of a single man.

In 312, the Emperor Constantine defeated his principal rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Accounts of the battle describe how Constantine saw a sign in the heavens portending his victory. Eusebius, Constantine’s principal biographer, describes the sign as the Chi Rho, the first two letters in the Greek spelling of the name Christos.

After that victory Constantine became the principal patron of Christianity. In 313 he issued the Edict of Milan which granted religious toleration. Although Christianity would not become the official religion of Rome until the end of the fourth century, Constantine’s imperial sanction of Christianity transformed its status and nature. Neither imperial Rome nor Christianity would be the same after this moment. Rome would become Christian, and Christianity would take on the aura of imperial Rome.

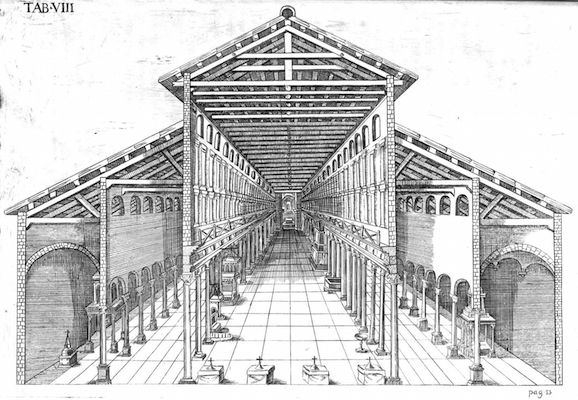

The transformation of Christianity is dramatically evident in a comparison between the architecture of the pre-Constantinian church and that of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian church. Emperors for centuries had been responsible for the construction of temples throughout the Roman Empire, so it was natural for Constantine to want to construct edifices in honor of Christianity.

In creating these churches, Constantine and his architects confronted a major challenge: what should be the physical form of the church? Clearly the traditional form of the Roman temple would be inappropriate both from associations with pagan cults but also from the difference in function. Temples served as treasuries and dwellings for the cult; sacrifices occurred on outdoor altars with the temple as a backdrop. This meant that Roman temple architecture was largely an architecture of the exterior. Since Christianity was a mystery religion that demanded initiation to participate in religious practices, Christian architecture put greater emphasis on the interior. The Christian churches needed large interior spaces to house the growing congregations and to mark the clear separation of the faithful from the unfaithful. At the same time, the new Christian churches needed to be visually meaningful. The buildings needed to convey the new authority of Christianity. These factors were instrumental in the formulation during the Constantinian period of an architectural form that would become the core of Christian architecture to our own time: the Christian Basilica.

The basilica model was adopted in the construction of Old St. Peter’s church in Rome. What stands today is New St. Peter’s church, which replaced the original during the Italian Renaissance. Whereas the original Roman basilica was rectangular with at least one apse, usually facing North, the Christian builders made several symbolic modifications. Between the nave and the apse, they added a transept, which ran perpendicular to the nave. This addition gave the building a cruciform shape to memorialize the Crucifixion. The apse, which held the altar and the Eucharist, now faced East, in the direction of the rising sun[1].

The Anatomy of a Christian Church

Early church architecture did not draw its form from Roman temples, as the latter did not have large internal spaces where worshipping congregations could meet. It was the Roman basilica, used for meetings, markets and courts of law that provided a model for the large Christian church and that gave its name to the Christian basilica.

The three most important elements within the basilica plan are:

The nave – the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type building, the strict definition of the term “nave” is restricted to the central aisle.

The transept -a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the edifice. In churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform (“cross-shaped”) pattern.

The apse – a semicircular recess, often covered with a hemispherical vault. In church architecture it is generally the name given to where the altar is placed or where the clergy are seated.

Most cathedrals and great churches have a cruciform ground plan. In churches of Western European tradition, the plan is usually longitudinal, in the form of the so-called Latin Cross with a long nave crossed by a transept.

Many of the earliest churches of Byzantium have a square plan in which the nave, chancel and transept arms are of equal length forming a Greek cross, the crossing generally surmounted by a dome became the common form in the Orthodox Church

Before Emperor Constantine’s acceptance, Christianity had a marginal status in the Roman world. Attracting converts in the urban populations, Christianity appealed to the faithful’s desires for personal salvation. By the middle of the fourth century, Christianity under imperial patronage had become a part of the establishment. The elite of Roman society were becoming new converts.

Such an individual was Junius Bassus, a member of a senatorial family. His father had held the position of Praetorian prefect, which involved administration of the Western Empire. Junius Bassus held the position of praefectus urbi for Rome. In his role as prefect, Junius Bassus was responsible for the administration of the city of Rome. When he died at the age of 42 in the year 359, a sarcophagus was made for him. As recorded in an inscription on the sarcophagus, Junius Bassus had become a convert to Christianity shortly before his death.

The style and iconography of this sarcophagus reflects the transformed status of Christianity. This is most evident in the image at the center of the upper register. Before the time of Constantine, the figure of Christ was rarely directly represented, but here on the Junius Bassus sarcophagus we see Christ prominently represented not in a narrative representation from the New Testament but in a formula derived from Roman Imperial art. The traditio legis (“giving of the law”) was a formula in Roman art to give visual testament to the emperor as the sole source of the law.

Already at this early period, artists had articulated identifiable formulas for representing Saints Peter and Paul. Peter was represented with a bowl haircut and a short-cropped beard, while the figure of Paul was represented with a pointed beard and usually a high forehead. In paintings, Peter has white hair and Paul’s hair is black. The early establishment of these formulas was undoubtedly a product of the doctrine of apostolic authority in the early church. Bishops claimed that their authority could be traced back to the original Twelve Apostles.

Peter and Paul held the status as the principal apostles. The Bishops of Rome have understood themselves in a direct succession back to St. Peter, the founder of the church in Rome and its first bishop. The popularity of the formula of the traditio legis in Christian art in the fourth century was due to the importance of establishing orthodox Christian doctrine.

In contrast to the established formulas for representing Saints Peter and Paul, early Christian art reveals two competing conceptions of Christ. The youthful, beardless Christ, based on representation of Apollo, vied for dominance with the long-haired and bearded Christ, based on representations of Jupiter or Zeus. The feet of Christ in the Junius Bassus relief rest on the head of a bearded, muscular figure, who holds a billowing veil spread over his head. This is another formula derived from Roman art. The figure can be identified as the figure of Caelus, or the heavens. Recall back to the breastplate in the Augustus of Primaporta; in the context of the Augustan statue, the figure of Caelus signifies Roman authority and its rule of everything earthly, that is, under the heavens. In the Junius Bassus relief, Caelus’s position under Christ’s feet signifies that Christ is the ruler of heaven[2].

We can determine some intentionality in the inclusion of the Old and New Testament scenes. For example, the image of Adam and Eve shown covering their nudity after the Fall was intended to refer to the doctrine of Original Sin that necessitated Christ’s entry into the world to redeem humanity through His death and resurrection. Humanity is thus in need of salvation from this world.

The suffering of Job on the left-hand side of the lower register conveyed the meaning how even the righteous must suffer the discomforts and pains of this life. Job is saved only by his unbroken faith in God. The scene of Daniel in the lion’s den to the right of the Entry into Jerusalem had been popular in earlier Christian art as another example of how salvation is achieved through faith in God.

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus

The Byzantine Empire

In 313, the Roman Empire legalized Christianity, beginning a process that would eventually dismantle its centuries-old pagan tradition. Not long after, emperor Constantine transferred the empire’s capital from Rome to the ancient Greek city of Byzantion (modern Istanbul). Constantine renamed the new capital city “Constantinople” (“the city of Constantine”) after himself and dedicated it in the year 330. With these events, the Byzantine Empire was born—or was it?

The history of Byzantium is remarkably long. If we reckon the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from the dedication of Constantinople in 330 until its fall to the Ottomans in 1453, the empire endured for some 1,123 years.

Scholars typically divide Byzantine history into three major periods: Early Byzantium, Middle Byzantium, and Late Byzantium. But it is important to note that these historical designations are the invention of modern scholars rather than the Byzantines themselves. Nevertheless, these periods can be helpful for marking significant events, contextualizing art and architecture, and understanding larger cultural trends in Byzantium’s history.

Early Byzantine

Generally speaking, Byzantine art differs from the art of the Romans in that it is interested in depicting that which we cannot see—the intangible world of Heaven and the spiritual. Thus, the Greco-Roman interest in depth and naturalism is replaced by an interest in flatness and mystery. Surviving Byzantine art is mostly religious and, for the most part, highly conventionalized, following traditional models that translate their carefully controlled church theology into artistic terms. Painting in frescoes, mosaics, and illuminated manuscripts, and on wood panels were the main, two-dimensional media. Figurative sculpture was very rare except for small, carved ivories.

Early Byzantine architecture drew upon the earlier elements of Roman architecture. After the fall of the Western Empire, several churches were built as centrally planned structures. However, stylistic drift, technological advancement, and political and territorial changes gradually resulted in the Greek-cross plan in church architecture. Buildings increased in geometric complexity. Brick and plaster were used in addition to stone for the decoration of important public structures. Classical orders were used more freely. Mosaics replaced carved decoration. Complex domes rested upon massive piers, and windows filtered light through thin sheets of alabaster to softly illuminate interiors.

One of the early Christian churches were built during this period included the famed Hagia Sophia, or Church of Holy Wisdom, built by Isidorus of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles in the sixth century under Emperor Justinian. Like most Byzantine churches of this time, the Hagia Sophia is centrally planned, with the dome serving as its focal point.

The vast interior has a complex structure. The nave is covered by a central dome that at its maximum is over 180 feet from floor level and rests on an arcade of 40 arched windows. Although the dome appears circular at first glance, repairs to its structure have left it somewhat elliptical, with its diameter varying between 101 and nearly 103 feet.

The dome of Hagia Sophia has spurred particular interest for many art historians, architects, and engineers because of the innovative way the original architects envisioned it. The cupola is carried on four, spherical, triangular pendentives, an element that was first fully realized in this building.

The pendentives implement the transition from the circular base of the dome to the rectangular base below to restrain the lateral forces of the dome and allow its weight to flow downwards. They were later reinforced with buttresses.

At the western entrance side and the eastern liturgical side are arched openings that are extended by half domes of identical diameter to the central dome and carried on smaller semi-domed exedras. A hierarchy of dome-headed elements creates a vast, oblong interior crowned by the central dome, with a span of 250 feet.

The Imperial Gate, reserved only for the emperor, was the main entrance of the cathedral. A long ramp from the northern part of the outer narthex leads up to the upper gallery, which was traditionally reserved for the empress and her entourage. It is laid out in a horseshoe shape that encloses the nave until it reaches the apse.

Hagia Sophia, Istambul

One of the most important surviving examples of Byzantine architecture and mosaic work is San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy . It was begun in 526 or 527 under Ostrogothic rule. It was consecrated in 547 and completed soon after.

One of the most famous images of political authority from the Early Byzantine period is the mosaic of the Emperor Justinian and his court in the sanctuary of the church of San Vitale. This image is an integral part of a much larger mosaic program in the chancel. A major theme of this mosaic program is the authority of the emperor in the Christian plan of history.

The mosaic program can also be seen to give visual testament to the two major ambitions of Justinian’s reign: as heir to the tradition of Roman Emperors, Justinian sought to restore the territorial boundaries of the Empire. As the Christian Emperor, he saw himself as the defender of the faith. As such it was his duty to establish religious uniformity or Orthodoxy throughout the Empire.

In the mosaic Justinian is posed frontally in the center. He is haloed and wears a crown and a purple imperial robe. He is flanked by members of the clergy on his left with the most prominent figure the Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna being labelled with an inscription. To Justinian’s right appear members of the imperial administration identified by the purple stripe, and at the very far left side of the mosaic appears a group of soldiers.

This mosaic thus establishes the central position of the Emperor between the power of the church and the power of the imperial administration and military. Like the Roman Emperors of the past, Justinian has religious, administrative, and military authority.

The clergy and Justinian carry in sequence from right to left a censer, the gospel book, the cross, and the bowl for the bread of the Eucharist. This identifies the mosaic as the so-called Little Entrance which marks the beginning of the Byzantine liturgy of the Eucharist. Justinian’s gesture of carrying the bowl with the bread of the Eucharist can be seen as an act of homage to the True King who appears in the adjacent apse mosaic. Justinian is thus Christ’s vice-regent on earth, and his army is actually the army of Christ as signified by the Chi-Rho on the shield.

Popular Early Monograms of Christianity

A Christogram is a monogram or combination of letters that forms an abbreviation for the name of Jesus Christ, traditionally used as a religious symbol within the Christian Church.

The symbolism of the early Church was characterized by being understood by initiates only, while after the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire during the 4th century more recognizable symbols entered in use. Below are some of the most common forms that you will see:

Chi-Rho: one of the earliest forms of Christogram, formed by superimposing the first two (capital) letters—chi and rho (ΧΡ)—of the Greek word ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ (Christos) in such a way that the vertical stroke of the rho intersects the center of the chi.

Staurogram (Tau-Rho):first used to abbreviate stauros (σταυρός), the Greek word for cross, in very early New Testament manuscripts and may visually have represented Jesus on the cross. It is often used in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages as a variant of the Chi-Rho.

IX (Iota-Chi): a type of early Christian monogram looking like the spokes of a wheel, sometimes within a circle. The IX monogram is formed by the combination of the letter “I” or Iota for Iesous (Ιησους, Jesus in Greek) and “X” or Chi for Christos (Χριστος, Christ in Greek). The spokes can also be stand-alone, without the circle.

IHS/JHS: In the Latin-speaking Christianity of medieval Western Europe (and so among Catholics and many Protestants today), the most common Christogram became “IHS” or “IHC”, denoting the first three letters of the Greek name of Jesus, ΙΗΣΟΥΣ, iota-eta-sigma, or ΙΗΣ. Because the Latin-alphabet letters I and J were not systematically distinguished until the 17th century, “JHS” and “JHC” are equivalent to “IHS” and “IHC”.

Closer examination of the Justinian mosaic reveals an ambiguity in the positioning of the figures of Justinian and the Bishop Maximianus. Overlapping suggests that Justinian is the closest figure to the viewer, but when the positioning of the figures on the picture plane is considered, it is evident that Maximianus’s feet are lower on the picture plane which suggests that he is closer to the viewer. This can perhaps be seen as an indication of the tension between the authority of the Emperor and the church.

Paradise and Power, San Vitale

Middle Byzantine

The Middle Byzantine period followed a period of crisis for the arts called the Iconoclastic Controversy, when the use of religious images was hotly contested. Iconoclasts (those who worried that the use of images was idolatrous), destroyed images, leaving few surviving images from the Early Byzantine period. Fortunately for art history, those in favor of images won the fight and hundreds of years of Byzantine artistic production followed.

Broadly defined, iconoclasm is defined as the destruction of images. In Christianity, iconoclasm has generally been motivated by people who adopt a literal interpretation of the Ten Commandments, which forbid the making and worshiping of graven images. The period after the reign of Justinian I (527–565) witnessed a significant increase in the use and veneration of images, which helped to trigger a religious and political crisis in the empire. As a result, aniconic sentiment grew, culminating in two periods of iconoclasm—the First Iconoclasm (726–87) and the Second Iconoclasm (814–42)—which brought the Early Byzantine period to an end.

After the death of the last Iconoclast emperor Theophilos, his young son Michael III, with his mother the regent Theodora and Patriarch Methodios, summoned the Synod of Constantinople in 843 to bring peace to the Church. At the end of the first session, on the first day of Lent, all made a triumphal procession from the Church of Blachernae to Hagia Sophia to restore the icons to the church in an event called the Feast of Orthodoxy.

Imagery, it was decided, is an integral part of faith and devotion, making present to the believer the person or event depicted on them. However, the Orthodox makes a clear doctrinal distinction between the veneration paid to icons and the worship which is due to God alone.

After the end of iconoclasm, a new mosaic was dedicated in the Hagia Sophia under the Patriarch Photius and the Macedonian emperors Michael III and Basil I. The mosaic is located in the apse over the main alter and depicts the Theotokos, or the Mother of God. The image, in which the Virgin Mary sits on a throne with the Christ child on her lap, is believed to be a reconstruction of a sixth-century mosaic that was destroyed during the Iconoclasm.

The image of the Virgin and Child is a common Christian image, and the mosaic depicts Byzantine innovations and the standard style of the period. The Virgin’s lap is large. Christ sits nestled between her two legs. The figures’ faces are depicted with gradual shading and modeling that provides a sense of realism that contradicts the schematic folding of their drapery.

Their drapery is defined by thick, harsh folds delineated by contrasting colors: the Virgin in blue and Christ in gold. The two frontal figures sit on an embellished gold throne that is tilted to imply perspective. This attempt is a new addition in Byzantine art during this period. The space given to the chair contradicts the frontality of the figures, but it provides a sense of realism previously unseen in Byzantine mosaics.

Theotokos mosaic, apse of the Hagia Sophia

Late Byzantine

The period of Late Byzantium saw the decline of the Byzantine Empire during the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries. Although the capital city of Constantinople and the empire as a whole prospered as a connection between east and west traders, Byzantium continually dealt with threats from the Ottoman Turks to the east and the Latin Empire to the west.

Between 1204 and 1261, the Byzantine Empire suffered another crisis: the Latin Occupation. During the Fourth Crusades, Crusaders from Western Europe invaded and captured Constantinople in 1204, temporarily toppling the empire in an attempt to bring the eastern empire back into the fold of western Christendom. By 1261, the Byzantine Empire was free of its western occupiers and stood as an independent empire once again, albeit markedly weakened)—the breadth of the empire had shrunk and so had its power. Nevertheless, Byzantium survived until the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453. In spite of this period of diminished wealth and stability, the arts continued to flourish in the Late Byzantine period, much as it had before.

Although Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453—bringing about the end of the Byzantine Empire—Byzantine art and culture continued to live on in its far-reaching outposts, as well as in Greece, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire, where it had flourished for so long. When the Renaissance was first emerging, it borrowed heavily from the traditions of Byzantium. Cimabue’s Madonna Enthroned of 1280–1290 is one of the earliest examples of the Renaissance interest in space and depth in panel painting, but the painting relies on Byzantine conventions and is altogether indebted to the arts of Byzantium.

So, while we can talk of the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, it is much more difficult to draw geographic or temporal boundaries around the empire, for it spread out to neighboring regions and persisted in artistic traditions long after its own demise.

The sack of Constantinople in 1204 marks the starting point of Late Byzantine Art, which lasted until the fifteenth century and spread beyond the borders of Byzantium. Art during this period began to change from the standards and styles seen in the Early and Middle periods of Byzantium rule. A renewed interest in landscapes and earthly settings arose in mosaics, frescoes, and psalters. This development eventually led to the demise of the gold background.

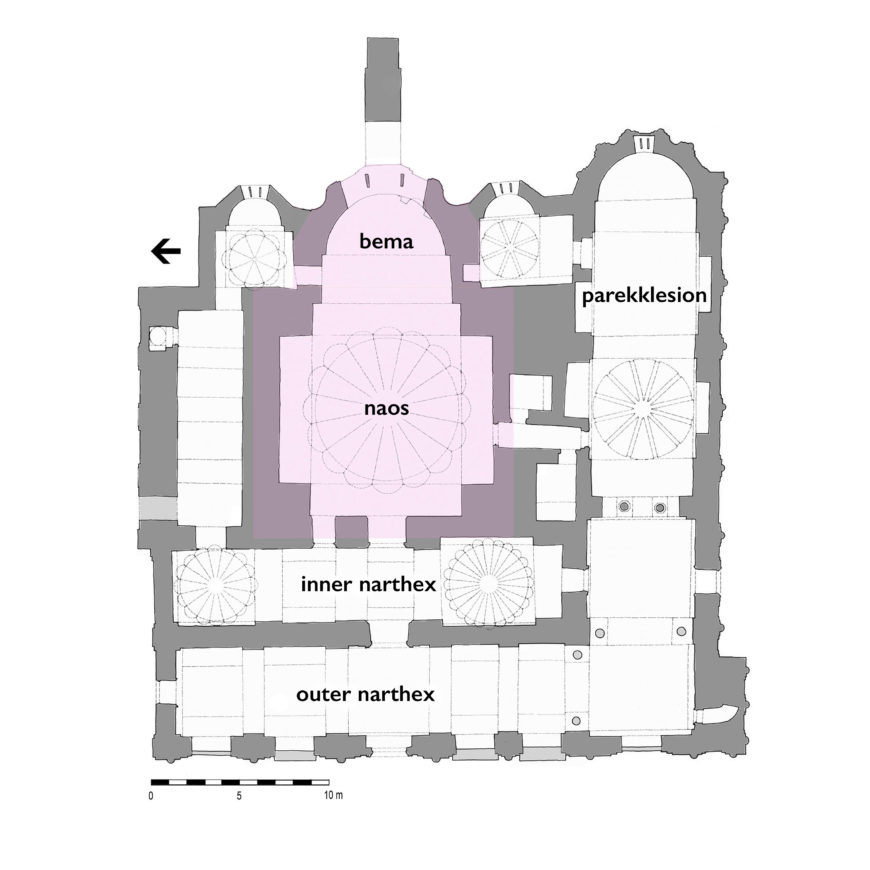

The Church of the Holy Savior in Chora was first built in Constantinople during the early fifth century. Its name references its location outside the city’s fourth-century walls. Even when the walls were expanded in the early fifth century by Theodosius II, the church maintained its name.

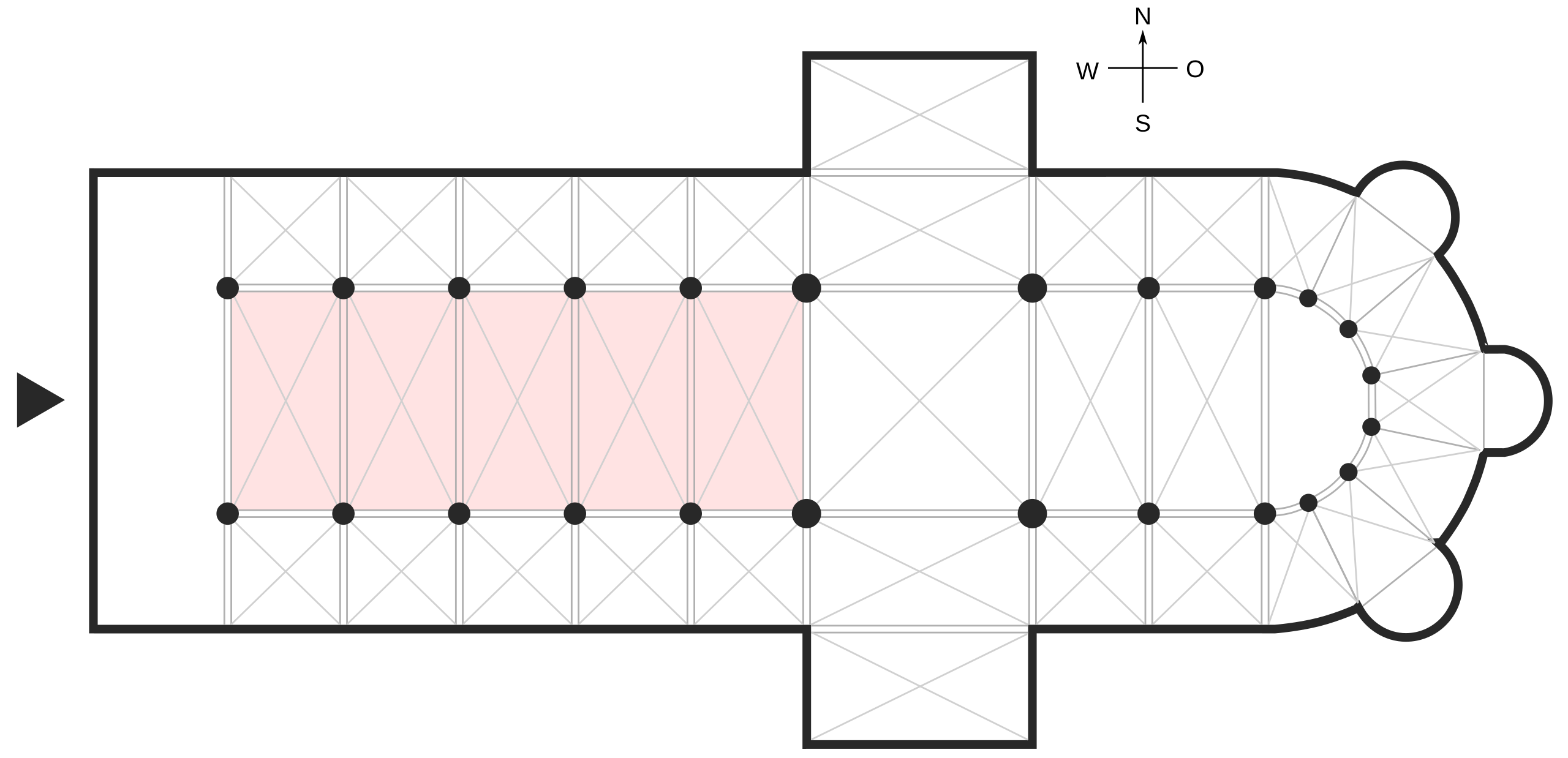

The Chora Church that stands today is the result of its third stage of construction. This building and the interior decoration were completed between 1315 and 1321 under the Byzantine statesman Theodore Metochites, whose additions and reconstruction in the fourteenth century enlarged the ground plan from the original small, symmetrical church into a large, asymmetrical square that consists of three main areas: an inner and outer narthex or entrance hall, the naos or main chapel, the side chapel (known as the parecclesion) that serves as a mortuary chapel and held eight tombs that were added after the area was initially decorated.

Mosaic work was still popular in the Late Byzantine period, but frescoes and the depiction of narrative cycles began to increase in popularity to become the primary decoration in churches. This transition is seen in the Chora Church, which was initially decorated in mosaic, with the final wing decorated with wall paintings. The shift in media changed the subjects depicted.

Mosaics of single scenes and figures were replaced in favor of frescoed narrative cycles and biblical stories. The rendering of the figures also began to change. Artists now relied less on sharp, schematic folds and patterns and instead use softer, more subtle modeling and shading. While sharp folds in the drapery can still be found in images from this period, these folds are rendered in similar, not complimentary, colors and shades. Furthermore, the bodies appear to have mass and weight. The figures no longer float or hover on their toes but stand on their feet. This allows for the addition of movement and energy in the painted figures and an overall increase of drama and emotion.

Picturing Salvation: Chora’s brilliant Byzantine mosaics and frescoes

The depictions of Christ in the Chora Church differ greatly from those of the third and fourth centuries. Recalling Early Christian art, Christ often appears clean shaven and youthful, sometimes cast as the Good Shepherd who tends and rescues his flock from danger. At a time when Christianity was illegal, Christians would have found such imagery of a protector reassuring.

By the fourteenth century, when Theodore Metochites funded the interior decoration, Christianity was no longer a fledgling faith; it was a state religion in which even the emperor recognized Christ as the ultimate authority. The images of Christ in the frescoes and mosaics of the Chora Church depict an authoritative, bearded man who occupies the role of both savior and judge. As an archetypal symbol of authority and wisdom through the ages, the beard would have been a logical choice for the face of the most supreme leader.

- An exception to this rule: the apse of Old St. Peter’s basilica faced West to commemorate the church’s namesake, who, according to the popular narrative, was crucified upside down. ↵

- Placing the foot atop another figure is a motif that has represented control and domination since Early Antiquity. Recall, for example, the vanquishing of the Lullubi in the Stela of Naram-Sin or the defeated foreigners in the Narmer Palette. Therefore, this scene could also refer to, and has been interpreted as, the victory of Christianity over pagan Rome. ↵

a religion centered on secret or mystical rites for initiates, especially any of a number of cults popular during the late Roman Empire.

the religious rite of sprinkling water onto a person's forehead or of immersion in water, symbolizing purification or regeneration and admission to the Christian Church.

a term first used by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism or ethnic religions other than Judaism. Alternative terms in Christian texts were hellene, gentile, and heathen. During and after the Middle Ages, the term paganism was applied to any non-Christian religion, and the term presumed a belief in false god(s).

the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists such as musicians, painters, and sculptors

the action or practice of burying the dead.

an underground cemetery consisting of a subterranean gallery with recesses for tombs, as constructed by the ancient Romans.

the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thus asserting an underlying unity and allowing for an inclusive approach to other faiths.

a poem, word puzzle, or other composition in which certain letters in each line form a word or words.

a small dome, especially a small dome on a drum on top of a larger dome, adorning a roof or ceiling.

a curved triangle of vaulting formed by the intersection of a dome with its supporting arches.

an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall

an antechamber, porch, or distinct area at the western entrance of some early Christian churches, separated off by a railing and used by catechumens, penitents, etc.

A Germanic group who had a large empire near the Black Sea, and who migrated westward between the 3rd and 5th centuries to expand their rule.

the space around the altar.

the absence of artistic representations of either the natural and supernatural worlds, or certain figures in religion

Mother of God (used in the Eastern Orthodox Church as a title of the Virgin Mary).