Who Owns Culture?: the Preservation and Destruction of Cultural Heritage

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Evaluate the concepts of cultural heritage and appraise the ownership of select works of art.

Our cultural heritage defines our humanity. Cultural diversity, like biodiversity, plays a quantifiable and crucial part in the health of the human species. An attack on cultural heritage in one part of the world is an attack on us all—on all of humanity. But cultural diversity is under grave threat around the globe. This wanton vandalism and destruction is not collateral damage—it’s a part of a ruthless wave of cultural and ethnic cleansing inseparable from the persecution of the communities that created these cultural gems. It’s also part of a cycle of theft and profit that finances the activities of extremists and terrorists. Any loss of cultural heritage is a loss of our common memory. It imperils our ability to learn, to build experiences, and to apply the lessons of the past to the present and the future—Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations, 12 April 2016

Looking Forward

Almost daily there are reports of the destruction and looting of art and objects of cultural heritage of local, regional, national, and international significance, notably coming out of the Middle East, but also from many other places in the world. Popular books and movies, such as The Rape of Europa, The Monuments Men, and The Woman in Gold, have brought more attention to the subject, especially in regard to outrages perpetrated during World War II, while scholars, policymakers, lawyers, conservationists, and forensic scientists are intimately involved in combating atrocities currently being committed. Cultural property crime is not, however, a new phenomenon, but a tactic employed over millennia across continents and against many different cultural groups for a variety of reasons.A thematic survey that reflects upon the looting and destruction of art and cultural heritage offers us the opportunity to engage with a potent subject that can elicit cultural empathy, to critically examine a historical and contemporary societal problem that affects our present and future, to examine our own attitudes and values, and to consider how art intersects with issues of power[1].

Of particular importance are issues of identity and contestation of power over objects of cultural heritage. Some questions to keep in mind as you progress through this chapter include:

- What objects have been held by various cultures and rulers as being imbued with power?

- Who has chosen to co-opt, usurp, or destroy particular works, and for what reasons?

- Who has obtained objects in the hopes of transferring a civilizing aura and promoting their cultural enrichment and status?

- What objects have been subject to iconoclasm, and why?

- What economic considerations might be present, and what are the ramifications of the sale of culturally significant objects?

- And, perhaps most importantly, when has the destruction of those objects been a harbinger of or a corollary to the destruction of an entire culture?

Since the reverberations of historical and contemporary looting are felt in the present, it is also important to consider society’s ethical obligations and current debate over contested objects of cultural heritage.

What is Cultural Heritage?

We often hear about the importance of cultural heritage. But what is cultural heritage? And whose heritage is it? Whose national heritage, for example, does the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci belong to? Is it French or Italian?

First of all, let’s have a look at the meaning of the words. Heritage is a property, something that is inherited, passed down from previous generations. In the case of cultural heritage, the heritage doesn’t consist of money or property, but of culture, values, and traditions. Cultural heritage implies a shared bond, our belonging to a community. It represents our history and our identity; our bond to the past, to our present, and the future.

Tangible and intangible cultural heritage

Cultural heritage often brings to mind artifacts (paintings, drawings, prints, mosaics, sculptures), historical monuments and buildings, as well as archaeological sites. But the concept of cultural heritage is even wider than that and has gradually grown to include all evidence of human creativity and expression: photographs, documents, books and manuscripts, and instruments, etc. either as individual objects or as collections. Today, towns, underwater heritage, and the natural environment are also considered part of cultural heritage since communities identify themselves with the natural landscape.

Moreover, cultural heritage is not only limited to material objects that we can see and touch. It also consists of immaterial elements: traditions, oral history, performing arts, social practices, traditional craftsmanship, representations, rituals, knowledge and skills transmitted from generation to generation within a community.

Intangible heritage therefore includes a dizzying array of traditions, music and dances such as tango and flamenco, holy processions, carnivals, falconry, Viennese coffee house culture, the Azerbaijani carpet and its weaving traditions, Chinese shadow puppetry, the Mediterranean diet, Vedic Chanting, Kabuki theatre, the polyphonic singing of the Aka of Central Africa (to name a few examples).

The importance of protecting cultural heritage

But cultural heritage is not just a set of cultural objects or traditions from the past. It is also the result of a selection process: a process of memory and oblivion that characterizes every human society constantly engaged in choosing—for both cultural and political reasons—what is worthy of being preserved for future generations and what is not.

All peoples make their contribution to the culture of the world. That’s why it’s important to respect and safeguard all cultural heritage, through national laws and international treaties. Illicit trafficking of artifacts and cultural objects, pillaging of archaeological sites, and destruction of historical buildings and monuments cause irreparable damage to the cultural heritage of a country. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), founded in 1954, has adopted international conventions on the protection of cultural heritage, to foster intercultural understanding while stressing the importance of international cooperation.

The protection of cultural property is an old problem. One of the most frequently recurring issues in protecting cultural heritage is the difficult relationship between the interests of the individual and the community, the balance between private and public rights.

Ancient Romans established that a work of art could be considered part of the patrimony of the whole community, even if privately owned. For example, sculptures decorating the façade of a private building were recognized as having a common value and couldn’t be removed, since they stood in a public site, where they could be seen by all citizens.

In his Naturalis Historia the Roman author Pliny the Elder (23-79 C.E.) reported that the statesman and general Agrippa placed the Apoxyomenos, a masterpiece by the very famous Greek sculptor Lysippos, in front of his thermal baths. The statue represented an athlete scraping dust, sweat and oil from his body with a particular instrument called a “strigil.” Emperor Tiberius deeply admired the sculpture and ordered it be removed from public view and placed in his private palace. The Roman people rose up and obliged him to return the Apoxyomenos to its previous location, where everyone could admire it.

Whose cultural heritage?

The term cultural heritage typically conjures up the idea of a single society and the communication between its members. But cultural boundaries are not necessarily well-defined. Artists, writers, scientists, craftsmen and musicians learn from each other, even if they belong to different cultures, far removed in space or time. Just think about the influence of Japanese prints on Paul Gauguin’s paintings, or of African masks on Pablo Picasso’s works. Or you could also think of western architecture in Liberian homes in Africa. When the freed African American slaves went back to their homeland, they built homes inspired by the neoclassical style of mansions on American plantations. American neoclassical style was in turn influenced by the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, who had been influenced by Roman and Greek architecture.

Let’s take another example, that of the Mona Lisa painted in the early sixteenth century by Leonardo da Vinci and displayed at the Musée du Louvre in Paris. From a modern point of view, whose national heritage does the Mona Lisa belong to?

Leonardo was a very famous Italian painter, that’s why the Mona Lisa is obviously part of the Italian cultural heritage. When Leonardo went to France, to work at King Francis I’s court, he probably brought the Mona Lisa with him. It seems that in 1518 King Francis I acquired the Mona Lisa, which therefore ended up in the royal collections: that’s why it is obviously part of the French national heritage, too. This painting has been defined as the best known, the most visited, the most written about and the most parodied work of art in the world: as such, it belongs to the cultural heritage of all mankind.

Cultural heritage passed down to us from our parents must be preserved for the benefit of all. In an era of globalization, cultural heritage helps us to remember our cultural diversity, and its understanding develops mutual respect and renewed dialogue amongst different cultures.

A Culture in Crisis

We shall begin with a provocative question: is culture in crisis?

In recent years, particularly since the rise of ISIS’ destructive activities in the Middle East, it’s become common to see articles in the news media as well as in academic journals on the theme of “cultural heritage in crisis.” You could say it’s a booming field. But how true is it?

It’s certainly true that cultural heritage is in danger of destruction, looting, or illicit trafficking in many places around the world. It’s also true that new types of threats to cultural heritage have developed in the last few decades.

They include:

- the easier movement of goods across national borders via online marketplaces like eBay

- the spread of global banking

- the outbreak of war and other forms of political instability and poverty

- the widespread availability of heavy machinery and explosives

Some regions—most recently the heritage-rich areas of the Middle East—have certainly experienced a marked increase in illicit trafficking in the context of ongoing political upheavals and conflicts.

But usage of the term “crisis” to describe the destruction of cultural heritage around the world is perhaps a misleading one. “Crisis” is a term that indicates a problem that has an urgent, yet temporary quality. However, the loss and destruction of cultural heritage is not new in human history and is not restricted by the duration of political instability in faraway lands. Many regions of the world, including the United States, face a longstanding and ongoing struggle to protect heritage in the face of numerous challenges, regardless of political, social, or economic security. It may be worth considering that the idea of “crisis” deceptively frames the destruction of heritage as a product of temporary instabilities that cease to be a problem once conflicts are over. In reality, conditions of “crisis” only really provide new opportunities for heritage destruction processes that were already happening and will continue happening after the “crisis” is over.

Let’s take a closer look at these processes. Broadly speaking, there are two types of threats:

- destruction of heritage sites and objects caused by war, poverty, and development initiatives

- the looting and trafficking of objects that frequently arises out of those contexts

Threats to cultural heritage: war

In wartime, destruction of heritage sites can be a result of collateral damage, for example, when a bomb targeting one location inadvertently hits another; or it can be the result of intentional damage, aimed to demoralize and insult the values and religious and cultural symbols of an enemy. It is often difficult to distinguish between collateral and intentional damage, and perpetrators may claim deliberate destruction was an accident in an attempt to avoid prosecution.

In the Syria conflict, for example, you’ve probably heard about the destruction caused by ISIS. However, the majority of damage to cities and to heritage has in fact not been caused by ISIS, but by the Syrian government’s campaign of relentless aerial bombardment, which has destroyed up to 70% of the fabric of the ancient city of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

On February 26, 2015, ISIS (also known as ISIL or the Islamic State) released a short clip showing the looting and destruction of the Mosul Museum in northern Iraq, as part of its propagandistic agenda.

You may have seen this clip, photographs from it, or something similar within the past several years. So, what is happening? Do you know of any other instances of destruction that might fit this pattern? You might have questions about the authenticity of the video or wonder if the sculptures were authentic or copies.

About half of the Assyrian objects are thought to be copies of the originals that are currently housed in the Iraq Museum. The Hatra King statues and the lamassu were authentic. The human-headed, winged beast, or lamassu, was among the few left in situ in Iraq. The lamassu were located across the river from Mosul, guarding the Palace of Sennacherib’s Nergal Gate (c. 700 BCE) for the past 2700 years in ancient Nineveh, once the world’s largest cities. There are other lamassu that were removed from the country in the mid- and late-nineteenth centuries that are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, the British Museum, and the Louvre. The most devastating losses from the Mosul Museum attack are the sculptures of the kings from Hatra since the majority of Hatrene work is still in Iraq, and the four destroyed here constitute roughly one-sixth of the known works. In addition, this period has been studied very little, and now we have lost much valuable information. Some artifacts that may have survived may be destined for the illicit antiquities market, because ISIS is funding many of their operations through such sales.

Prior to releasing the video of the atrocities committed in the Mosul Museum, ISIS had destroyed few sculptural artifacts. Most of the demolished architectural sites were Shia mosques or shrines and holy sites of the Yezidi but very little from the ancient world had yet been targeted. However, during March and April of 2015, ISIS rampaged through several ancient cities in the cradle of civilization: first, Nimrud, then on to Khorsabad, the medieval monastery of Mar Behnam, and Hatra. A mosque built over a church and dedicated to Yunus (Jonah; and the claimed location of his tomb); sacred to Jews, Christians, and Muslims, was demolished; and Palmyra was also targeted.

Palmyra: the modern destruction of an ancient city

Why are these sites being targeted? ISIS’s ideological claim for demolishing cultural heritage, especially sculpture, is toward the prohibition of idolatry. These iconoclastic attacks by an extremist group go well beyond that by deliberately targeting religious and cultural groups (past and present) that do or did not profess the same beliefs: an act of cultural cleansing. ISIS endeavors to erase a pre-Islamic past and any other belief system except its own to try and bring into being a world where, with no visual records or historical texts, the past is forgotten and only ISIS’s own interpretation of it exists. The group also brings attention to their cause, so they can recruit more members. The objects they loot, rather than destroy, are economic goods given even more value for their new scarcity in the market, where they can sell those objects to finance their extremist activity.

Referring to the cultural heritage of Iraq, UNESCO’s Director General declared in May 2015,

The deliberate destruction of cultural heritage is a war crime — it is used as a tactic of war, in a strategy of cultural cleansing that calls on us to review and renew the means by which we wish to respond and to defeat violent extremism.

The Iraqi ambassador Mohamed Ali Alhakim noted,

The destruction of cultural heritage aims to erase the multicultural history of Iraq that has been the hallmark of our country.

And though it’s easy to demonize a regime in a country far away, it’s important to remember that similar levels of destruction were caused by both the Axis powers and the Allies in World War II — for the Allies, most famously in Dresden, where a British and American aerial campaign in 1945 left more than 70% of the city in ruins. The neglect of the occupying U.S. forces in Iraq in 2003 famously led to the looting of the National Museum of Iraq, with thousands of objects lost, only half of which have returned, as well as the burning and destruction of Iraq’s magnificent national library, including hundreds of priceless manuscripts dating back to the 16th century. Deliberate or neglectful destruction of heritage has long been a key strategy of war, and perpetrators are rarely prosecuted for it.

The long history of the destruction of heritage shows us that the elimination of culture has always been viewed as a powerful tool of domination and as a key strategy for eliminating the value humans accord to their lives. In recent years, the destruction of heritage — whether through war, commercial exploitation, and/or looting — has been defined by UNESCO as a form of cultural cleansing. In taking human lives, oppressors erase the existence of individual people: but in destroying culture, the memory and identity of entire peoples are erased. It is not surprising to note, therefore, that the destruction of heritage is often a precursor to genocide. This is because in denying people their past, perpetrators also deny them a future.

More than forty years ago, the art historian Albert Elsen connected the problem directly to the classroom:

In 1977, no more explosive issue confronts the art world than the protection of Art. Fair question is whether as teachers and scholars we are doing the best job of educating our students to be aware of, comprehend, and deal with the problems of art’s protection…. We teach our students the engineering and iconography of a Gothic cathedrals, but not why they should be preserved.

Iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire

The systematic destruction of images seen as heretical is not unique to the conversation of Islamic extremism in the Middle East. An historical ideological debate about images that led to their widespread destruction was the Iconoclastic Controversy between 726–843 C.E. in the Byzantine Empire[2]. At the heart of the argument was the concern that images of Christ and the saints might displease God, due to their potential to be misused as idols. This was not a mere theoretical debate but one that acknowledged the power of icons and the idea that being on the wrong side meant the entire empire might lose God’s favor.

Iconoclasts argued that the reproduction or copy of the image of either Christ or the saints was an idolatrous, pagan violation of the Bible’s Second Commandment, which prohibited graven images. Iconoclasts claimed that the Eucharist, through Transubstantiation, was the only true image of Christ, because it was (miraculously) the same material as the prototype (literally becoming the body of Christ, rather than wood, paint, ivory, etc.). Further, they claimed that images confused the two natures of Christ by limiting the limitless Godhead through adulteration with earthly material, thus separating his divine and uncircumscribable nature from his human, material nature. Iconodules maintained that icons and images could teach the illiterate; aid in communication with Christ, because prayers ascend from the material world through the icon up to the immaterial Christ; and confirm the dual nature of Christ as human and divine in a manner analogous to the Incarnation.

With the exception of brief periods when two women with iconodule policies ruled Byzantium, images were destroyed in vast numbers during the Iconoclastic Controversy. Paintings and mosaics were whitewashed, others were chiseled away, and new, approved iconography, like crosses, were inserted, as in the apse mosaic in Saint Irene, Istanbul (c. 740 C.E.).

The Crucifixion and the Iconoclasts from the Chludov Psalter, created after the defeat of iconoclasm, shows the figure of the iconoclast Patriarch John VII the Grammarian, clad in red, whitewashing an icon.

Take a moment to reflect back upon our chapter on the Byzantine period: how might the destruction of many images created prior to 726 CE and the change in types of images made during the eighth and ninth centuries impact our current understanding of Byzantium?

Threats to cultural heritage: development, climate change, tourism, and natural disasters

Nevertheless, wartime destruction of heritage is only a small fraction of the overall loss of cultural heritage around the world. Much more significant and long-lasting is destruction due to urban development, mineral and resource extraction, climate change, tourism, and even natural disasters. For example, the ancient Buddhist site of Mes Aynak in Afghanistan is now threatened by Chinese mining interests, a situation made famous in the documentary, Saving Mes Aynak. Similarly, the push to expand resource extraction on public lands in the United States is also causing widespread loss of heritage, as at the Bears Ears National Monument, which was controversially reduced by 85% in a decision signed by President Trump in December 2017.

Although many heritage sites are preserved in order to encourage tourist revenue, such as that seen in Egypt, tourism can also cause massive destruction because of the large numbers of people it can attract and also because transforming a site into a tourist-friendly locale often profoundly transforms its meaning for local people, who may find their connections to a place have been erased. Such is the case at Dubrovnik, a city that was reconstructed by an international consortium of donors after the Balkan war and which now finds itself managing a Game of Thrones-inspired tourist influx that threatens to leave little of the original city behind, a destruction that some residents have characterized as worse than that during wartime.

Looting and the Appropriation of Objects

If destruction of heritage during times of conflict is akin to a relatively sudden death, looting is like a cancer that slowly erodes it. Looting is the theft of heritage items for sale on the antiquities market, most often to wealthy private buyers in the United States and Europe. The consequences of purchasing even small items like coins can be devastating for our knowledge about the past. Once an object is removed from its original environment, it instantly loses much of its ability to convey information about how people once lived.

Archaeologists call the environment in which an object is found, its context. Context is the object and its relationship to all the other objects and material in an archaeological site. The relationships between these objects is what enables archaeologists to recreate the past. As such, even the smallest objects, such as ancient coins, can provide powerful evidence about the lives of people in the past. While locals are often blamed for looting, it is important to point out that local looting is often subsistence looting and that it is only profitable because it responds to demand in wealthy countries. The antiquities market is vast, and as the Wall Street Journal reported in 2017, it has consequences far beyond just loss of our knowledge about the past, since much like drug trafficking, its profits fuel terrorism, criminal enterprises, and many other forms of criminal activity.

The work of the archaeologist is often central to the protection of cultural heritage. The availability of dynamite and bulldozers in the modern era has enabled widespread looting and the subsequent loss of site context and has created a class of orphaned objects that now pervade the art market. Looting of archaeological sites is a worldwide problem that often occurs in poor countries where local populations have few other resources and in rich nations such as the United States.

What is lost in these cases is not simply prized objects that vanish into private collections, but also the valuable information that is destroyed when the site’s sediments are disturbed and less salable materials destroyed. The video below examines just how much we can learn when a site is excavated with modern, scientific methods, and just how much knowledge of the human past is lost through looting.

The Looting of Cambodian Antiquities

Impact of Social Change: the many lives of the Parthenon

The social evolution of cultures and its accompanying changes can also impact, or even destroy, monuments. After the advent of Christianity, the Pantheon and Parthenon temples were rededicated as Christian structures. After the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Turks, the Christian Hagia Sophia became an Islamic mosque (1453-1935) and then later converted into a secular museum (1935-2020) when the Ottoman Empire was partitioned at the end of WWI. As of July 2020 it has controversially been reverted back into a mosque.

The Parthenon, as it appears today on the summit of the Acropolis, seems like a timeless monument—one that has been seamlessly transmitted from its moment of creation, some two and a half millennia ago, to the present. But this is not the case. In reality, the Parthenon has had instead a rich and complex series of lives that have significantly affected both what is left, and how we understand what remains.

It is illuminating to examine the Parthenon’s ancient lives: its genesis in the aftermath of the Persian sack of the Acropolis in 490 B.C.E.; its accretions in the Hellenistic and Roman eras; and its transformation as the Roman empire became Christian. Why was the building created, and how was it understood by its first viewers? How did its meanings change over time? And why did it remain so important, even in Late Antiquity, that it was converted from a polytheist temple into a Christian church?

Investigating the many lives of the Parthenon has much to tell us about how we perceive (and misperceive) this famous ancient monument. It is also relevant to broader debates about monuments and cultural heritage. In recent years, there have been repeated calls to tear down or remove contested monuments, for instance, statues of Confederate generals in the southern United States. While these calls have been condemned by some as ahistorical, the experience of the Parthenon offers a different perspective. What it suggests is that monuments, while seemingly permanent, are in fact regularly altered; their natural condition is one of adaptation, transformation, and even destruction.

The Genesis of the Parthenon, 480–432 BCE

The Parthenon we see today was not created ex novo. Instead, it was the final monument in a series, with perhaps as many as three predecessors. The penultimate work in this series was a marble building, almost identical in scale and on the same site as the later Parthenon, initiated in the aftermath of the First Persian War.

During the first Persian invasion of Greece in 492–490 B.C.E., Athens played a central role in the defeat of the Persians. Thus, it is not surprising that ten years later when the Persians returned to Greece, they made for Athens; nor that, when they took the city, they sacked it with particular fervor. In the sack, they paid special attention to the Acropolis, Athens’s citadel. The Persians not only looted the rich sanctuaries at the summit, but also burned buildings, overturned statues, and smashed pots.

When the Athenians returned to the ruins of their city, they faced the question of what to do with their desecrated sanctuaries. They had to consider not only how to commemorate the destruction they had suffered, but also how to celebrate, through the rebuilding, their eventual victory in the Persian Wars.

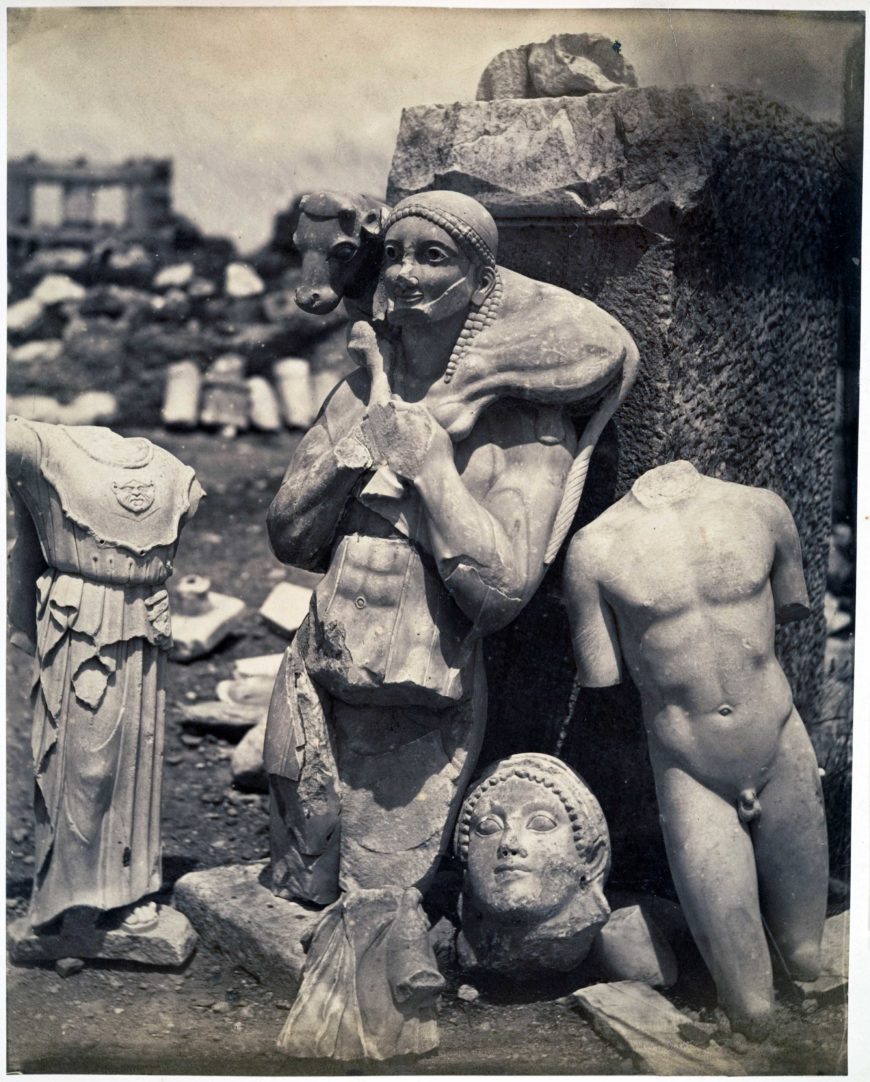

The Athenians found no immediate solution to their challenge. Instead, for the next thirty years they experimented with a range of strategies to come to terms with their history. They left the temples themselves in ruins, despite the fact that the Acropolis continued to be a working sanctuary. They did, however, rebuild the walls of the citadel, incorporating within them some fire-damaged materials from the destroyed temples. They also created a new, more level surface on the Acropolis through terracing; in this fill, they buried all the sculptures damaged in the Persian sack. These actions, most likely initiated in the immediate aftermath of the destruction, were the only major interventions on the Acropolis for over thirty years.

In the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the Athenians decided, finally, to rebuild. On the site of the great marble temple burned by the Persians, they constructed a new one: the Parthenon we know today. They set it on the footprint of the earlier building, with only a few alterations; they also re-used in its construction every block from the Older Parthenon that had not been damaged by fire. In their recycling of materials, the Athenians saved time and expense, perhaps as much as one-quarter of the cost of construction.

At the same time, their re-use had advantages beyond the purely pragmatic. As they rebuilt on the footprint of the damaged temple and re-used its blocks, the Athenians could imagine that the Older Parthenon was reborn—larger and more impressive, but still intimately connected to the earlier sanctuary.

While the architecture of the Parthenon referenced the past through re-use, the sculptures on the building did so more allusively, re-telling the history of the Persian Wars through myth. This re-telling is clearest on the metopes that decorated the exterior of the temple. These metopes had myths, for instance, the contest between men and centaurs, that recast the Persian Wars as a battle between good and evil, civilization and barbarism.

The metopes did not, however, depict this battle as one of effortless victory. Instead, they showed the forces of civilization challenged and sometimes overcome: men wounded, struggling, even crushed by the barbaric centaurs. In this way, the Parthenon sculptures allowed the Athenians to acknowledge both their initial defeat and their eventual victory in the Persian Wars, distancing and selectively transforming history through myth.

Thus, even in what might commonly be understood as the moment of genesis for the Parthenon, we can see the beginning of its many lives, its shifting significance over time. Left in ruins from 480 to 447 B.C.E., it was a monument directly implicated in the devastating sack of the Acropolis at the onset of the Second Persian War. As the Parthenon was rebuilt over the course of the following fifteen years, it became one that celebrated the successful conclusion to that war, even while acknowledging its suffering. This transformation in meaning presaged others to come, more nuanced and then more radical.

Hellenistic and Roman Adaptations

By the Hellenistic era if not before, the Parthenon had taken on a canonical status, appearing as an authoritative monument in a manner familiar to us today. It was not, however, untouchable. Instead, precisely because of its authoritative status, it was adapted, particularly by those who sought to present themselves as the inheritors of Athens’ mantle.

The Parthenon was altered by a series of aspiring monarchs, both Hellenistic and Roman. Their goal was to pull the monument, anchored in the canonical past, toward the contemporary. They did so above all by equating later victories with Athens’ now-legendary struggles against the Persians.

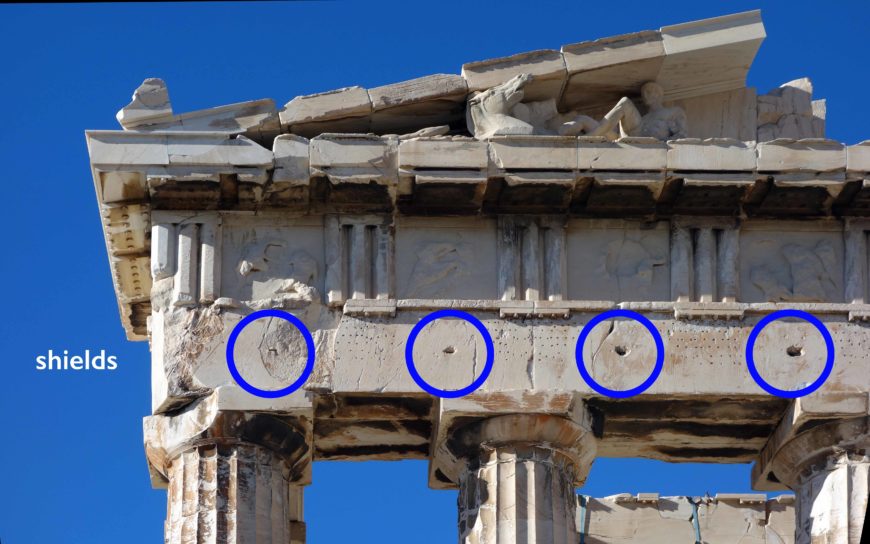

The first of these aspiring monarchs was the Macedonian king Alexander the Great. As he sought to conquer the Achaemenid Empire—alleging the Persian destruction of Greek sanctuaries one hundred and fifty years earlier—Alexander made good propagandistic use of the Parthenon. After his first major victory over the Persians in 334 B.C.E., the Macedonian king sent to Athens three hundred suits of armor and weapons taken from his enemies. Likely with Alexander’s encouragement, the Athenians used them to adorn the Parthenon. There are still faint traces of the shields, once prominently placed just below the metopes on the temple’s exterior. Melted down long ago due to their valuable metal content, the shields must have been a highly visible memento of Alexander’s victory—and also of Athens’ subordination to his rule.

Some two centuries later, another Hellenistic monarch set up a larger and more artistically ambitious dedication on the Acropolis. Erected just to the south of the Parthenon, the monument celebrated the Pergamene kings’ victory over the Gauls in 241 B.C.E. It also suggested that this recent success was equivalent to earlier mythological and historical victories, with monumental sculptures that juxtaposed Gallic battles with those of gods and giants, men and Amazons, and Greeks and Persians. Like the shield dedication of Alexander, the Pergamene monument made good use of its placement on the Acropolis. The dedication highlighted connections between the powerful new monarchs of the Hellenistic era and the revered city-state of Athens, paying homage to Athens’ history while appropriating it for new purposes.

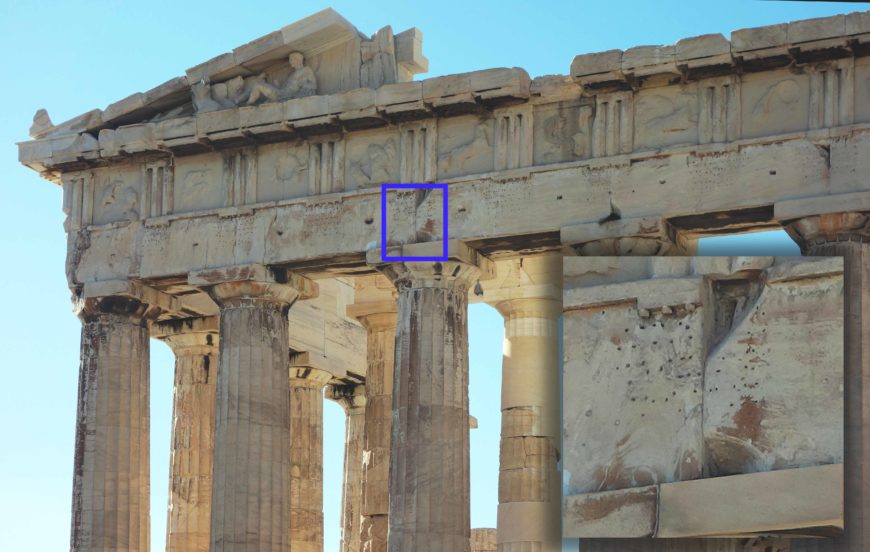

A final royal intervention to the Parthenon came in the time of the Roman emperor Nero. This was an inscription on the east facade of the Parthenon, created with large bronze letters in between Alexander’s previously dedicated shields. The inscription recorded Athens’ vote in honor of the Roman ruler and was likely put up in the early 60s C.E.; it was subsequently taken down following Nero’s assassination in 68. The inscription honored Nero by connecting him to Athens and to Alexander the Great, a model for the young philhellenic emperor. Its removal offered a different message. It was a deliberate and very public erasure of the controversial ruler from the historical record. In this, Nero’s inscription (and its removal) was perhaps the most striking rewriting of the Parthenon’s history—at least until Christian times.

Reviewing the Hellenistic and Roman adaptations of the Parthenon, it is easy to see them purely as desecrations: appropriations of a religious monument for political and propagandistic purposes. And the speedy removal of Nero’s inscription does support this reading, at least for the visually aggressive strategies of the Roman emperor. At the same time, the changes of the Hellenistic and Roman eras are also testimony to the continued vitality of the sanctuary. Due to the prestige of the Parthenon, formidable monarchs sought to stake their visual claims to power on what was by now a very old monument, over four centuries old by the time of Nero. By altering the temple and updating its meanings, they kept it young.

Early Christian Transformations

In ancient times, the most radical and absolute transformation of the Parthenon came as the Roman empire became Christian. At that point, the temple of Athena Parthenos was turned into an Early Christian church dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God). As with the rebuilding of the Parthenon in the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the decision to put a Christian church on the site of Athena’s temple was not just pragmatic but programmatic.

By transforming the polytheist sanctuary into a space of Christian worship, it provided a clear example of the victory of Christianity over traditional religion. At the same time, it also effectively removed, through re-use, an important and long-enduring center of polytheist cult. This removal through re-use was a characteristic strategy used by the Christians throughout the Roman Empire, from Turkey to Egypt to the German frontier. In all these places, it formed part of the often violent, yet imperially sanctioned, transition from polytheism to Christianity.

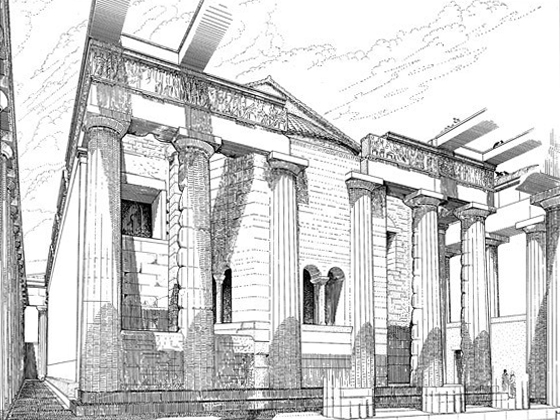

The Christian transformation of the Parthenon involved considerable adaptation of its architecture. The Christians needed a large interior space for congregation, unlike the polytheists, whose most important ceremonies took place at a separate altar, outdoors. To repurpose the building, the Christians renovated the inner cella of the Parthenon. They detached it from its exterior colonnade, added an apse that broke through the columns at the east end, and removed from the interior the statue of Athena Parthenos that had been the raison d’étre of the polytheist temple.

Other sculptures from the Parthenon suffered likewise from the Christians’ attentions. Most of the metopes—the lowest down and most visible of the Parthenon’s sculptures—were cut away, rendering them difficult to interpret or to use as a focus of polytheist cult. Only the south metopes with the centaurs were spared, perhaps because they overlooked the edge of the Acropolis and were thus hard to see. By contrast, the frieze (hidden between the exterior and interior colonnades) was left almost entirely intact, as were the high-up pediments. The differentiated treatment of the various sculptures on the Parthenon suggests negotiation between traditionalists and the more fervent of the contemporary Christians. Polytheists perhaps sacrificed the relatively small-scale and blatantly mythological metopes to keep the larger, better quality sculptures elsewhere on the monument. Examining the frieze, about one hundred sixty meters long and almost perfectly preserved, it seems like the polytheists got a good deal.

Later Alterations

By the end of the fifteenth century, following the Ottoman Turk conquest of the region, the Parthenon was later appropriated for use as a mosque. Soon after, it was then converted into a munitions store under the Ottoman occupation as they readied themselves for the 1687 Morean War, during which the building sustained major damage, including the loss of its roof, when the Venetians fired upon the structure during a siege against the Turks. More damage was sustained when the Venetians claimed the site and looted some sculptures while destroying others in the process. After the Venetians were repulsed in 1688, the Turks built a small mosque within the ruin. Lord Elgin received permission from the Ottoman Empire and removed more sculptures in 1801-2. Since then, the building has deteriorated further due to atmospheric pollution, recently undergoing a rigorous cleaning.

Within and beyond the ancient world, the Parthenon had many lives. Rather than ignoring them, it is useful to acknowledge these lives as contributions to the building’s extraordinary continuing vitality. At the same time, one might note that the biography of the Parthenon (though accessible to specialists) has been decidedly effaced by the way it is presented now. When contrasting its present-day state with the first photographs taken in the mid-nineteenth century, we can see how much has been intentionally removed: a Frankish tower by the entrance to the Acropolis, an Ottoman dome, mundane habitations.

In its current iteration, the Acropolis has been returned to something resembling its pristine Classical condition, with no reconstructed monuments dating later than the end of the 5th century B.C.E. This feels like a loss: a retardataire effort to reinstate a selective, approved version of the past and to erase the traces of a more difficult and complex history. As such it stands as an example, and perhaps also a warning, for our current historical moment.

What Can Be Done: Restitution, repatriation, and reconstruction

In repositioning the discussion of the current crisis to a discussion of how we are in fact currently experiencing the latest iteration of a long-standing problem with global reach, we can avoid simplistic solutions that propose that squashing the “bad guys” will solve the destruction and looting problem once and for all. Most importantly, it allows us to focus on the real driver of destruction: the demand in wealthy countries for heritage objects — a demand that ultimately fuels the entire antiquities trade — and the lax legislation that enables that trade to flourish. It also permits a conversation about related issues, for example the lack of public education about the antiquities trade, or problematic distinctions such as that between art — largely considered to be a private commodity subject to market demand, versus heritage — which is typically framed as “universal” and the patrimony of all.

Understanding that cultural heritage has been under threat for a very long time allows us to avoid short-term, crisis-based responses, and enables us to craft long-lasting, systemic solutions.

Napoléon, Hitler, the Taliban, and more recently ISIS have all resorted to the theft and destruction of meaningful objects of cultural heritage as a means, at least in part, of obliterating a culture’s identity and devastating the spirit of its people. But conversely, an object’s repatriation, restoration, or restitution can play an important role in reconciliation and in a culture’s resiliency. In response to contemporary manmade political situations and natural disasters, new scholarship is beginning to examine and theorize culture as a “basic need,” and to propose that emergency cultural aid be conceptualized, managed, and reconciled with other “basic needs” for survival.

While it may seem simple to catch and punish perpetrators for crimes related to antiquities trafficking and destruction, in fact a lack of public understanding of the problems associated with these crimes and limited heritage-related law enforcement capacity in many countries has meant that antiquities destruction and trafficking is less likely to be prosecuted than other criminal activities (despite clear links to terrorism, international crime, money laundering, and trafficking). But there are many things that can be done on the local level to support heritage workers and caretakers and protect heritage, and there are a number of organizations that are working hard to ensure that this occurs. There are many ways that you can help.

Many people are surprised to learn that legislation to protect antiquities is relatively weak or, in some cases, non-existent. Working to support and strengthen heritage protection legislation both locally and nationally, particularly when heritage is threatened by urban development or resource extraction, is one key way that ordinary citizens can contribute. There are some signs that wartime destruction is now coming under closer legal scrutiny, but most trafficked objects don’t come from wartime contexts.

One of the best ways for people to help save heritage is to remember that demand is the driver for looting and destruction. Governments can work to craft better legislation, prioritize better enforcement, greater funding, and vigorous prosecution for violators, but as long as there is a viable market for recently looted antiquities, they will appear on the market. Unfortunately, the vast majority of objects sold online are looted or fake. It’s important to remember that smaller items like coins, pots, beads, or small statuary are often easiest to traffic and easiest to sell without a record of provenance (or origin), or with a faked record of provenance. For an object to be legally sold, it cannot have been recently looted and must have been in a private collection for a certain amount of time.

Education is another key way to fight destruction and looting. Many ordinary people are unaware of the threat to cultural heritage and thus, are not aware that there is a problem at all. One of the most important ways to address the problem of the ongoing loss of global heritage is to incorporate education about the costs and consequences of global antiquities trade into school curricula and university syllabi or through local outreach in community organizations, libraries, churches, or other public settings. At the secondary school or university level, cultural heritage awareness can be integrated into existing curricula in fields like Anthropology, Archaeology, Art History, Ethics, History, International Affairs, Law, and Political Science. Journalists also play a key role in spreading knowledge and awareness of what we all lose when heritage is destroyed or trafficked.

Restitution and Repatriation: Laws, treaties, conventions

Laws respecting the return of cultural patrimony or its restitution (requires acknowledgement of culpability for removal of an object) evolved out of treaties signed at congresses or conventions concluding war, beginning with the 1815 Congress of Vienna after the Napoleonic Wars. It was here that the idea that cultural heritage connects people and territories with significant artistic or cultural objects first became entwined with laws. The treaty also enshrined the idea of the inviolability of sales contracts, which is not always compatible with stipulations of peace treaties. The Duke of Wellington pressured France to restore artworks to their countries of origin, establishing a model for the future. President Lincoln recognized the importance of monuments such as churches, libraries, and works of art and commissioned what became known as the Lieber Code to protect such cultural monuments. The code was printed in small pamphlets for Union Soldiers to carry into the field. Several other important conventions followed with more agreements addressing protection and restitution of cultural property:

- Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict with Regulations for the Execution for the Convention, 1954 (Hague Convention and Protocols of 1954)

- Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, 1970 UNESCO (1970 Convention on Illicit Traffic of Cultural Property)

- Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, 1972 UNESCO

Restitution: Hopi Tribal Council

There are several groups, such as the Holocaust Art Restitution Project (HARP), who act to reunite families and communities with their cultural inheritance. In 2015, they partnered with the Hopi Tribal Council to assist them in banning a French auction of the sacred Katsinam figurines. The Hopi have been fighting to reclaim these mask-like objects they assert were stolen years ago, many of which found their way to French auctions. In 2013, the Annenberg Foundation secretly bid on twenty-four of the items and secured twenty-one of them to return to the Hopi. The objects are considered living entities with divine spirits and are used in spiritual ceremonies, then retired and left to naturally disintegrate.

The case of the Hopi Katsinam is not an isolated or even unusual incident. It is estimated that over 90% of American Indian archaeological sites have been destroyed or looted. It is, perhaps, more likely that we will interact outside of the bounds of museums with American Indian artifacts than other historical objects, and so it is important to consider our ethical obligations[3].

The Role of Museums

We are still living with the ramifications of centuries of colonial domination. Major museums, especially those in the West, hold treasures obtained through conquest, revolution, colonial occupation, and the advantages of great wealth. Further, art museums have traditionally emphasized the aesthetic qualities of the object, often presenting a prized object alone in an illuminated transparent box. This display strategy hides not only the object’s original use — in a masquerade in West Africa, in a Buddhist temple, or on a church altar — but also has the effect of secularizing what was once held as sacred. This tension between the secular values of the encyclopedic museum (those museums with global collections often obtained through colonial ventures or through the donation of unprovenanced objects) which seeks to understand humanity across time and place, and the potentially more nationalistic sentiments of people who were colonized, is regularly played out in debates between archaeologists, museum directors, curators, and local populations.

This is, however, a complex discussion. In some cases, the cultures that created the objects no longer exist; in other instances, efforts to link objects to traditions that do endure have been criticized as too far-reaching. Some also argue that the values of commonality—of a shared universal heritage—are more important than national claims especially if they are made by governments sullied by political agendas. Clearly, this is not a debate for those looking for a well-defined moral high ground. If, on the other hand, we are looking for a forum in which to examine how we define identity, and upon what we can base reciprocal cultural respect, then cultural heritage offers enormous advantages.

The story of the Euphronios Krater is a case in point. The krater, a large ancient Greek punch bowl, was purchased by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and became one of their most celebrated objects, not only because of the pot’s record-breaking price, but because of its exceptional painting. The krater is now in a small regional museum in Italy, having been returned after it was discovered that the vase was likely looted from an ancient Etruscan tomb north of Rome. Questions linger about The Metropolitan’s acquisition and its willingness to overlook gaps in the pot’s provenance.

It is important to remember that for cultures throughout history and across the globe, images and objects are not inanimate and powerless, rather they maintain an intimate connection to what they represent — whether that is an ancestor, an image of a deity, or a loved one. In the West, we would do well to remember the power and efficacy of images.

Digital Reconstructions

New technology also can play a role in digitally preserving or reconstructing cultural heritage sites. CyArk provides one example; it a non-profit organization that creates 3D digital records with the goal of saving five hundred sites in the next five years. CyArk has partnered with the World Monuments Fund (WMF), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), the International Centre for the Study of Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), and many others. For example, one of their projects was to scan the Assyrian Collection of the British Museum.

After the destruction of the Mosul Museum collection, Matthew Vincent, a cyber archaeologist, doctoral candidate from the University of California at San Diego, and current Fellow at the Initial Training Network for Digital Cultural Heritage, and another Fellow, Chance Coughenour, initiated the digital cultural heritage Project Mosul.

The project gives power back to the global community through its mission to crowd-source photographs, digitally mesh them, and create a 3D replica of the no-longer extant works. While a team of experts works on the software, volunteers upload photographs, sort them, create point clouds to make a 3-D mesh and add texture, which makes the images. Anyone, including students, can go to their website and volunteer. Some tasks take very little technological know-how while others require some coding skills. The Mosul Museum did not have full registers or inventories of its holdings nor was it systematically visually documented with a catalog or digital archive, so the crowdsourcing is more than just a means of letting people participate; it is essential to the success of the project. Through the 3D reconstructions the public can actively counter the violence, loss, and sense of helplessness many feel upon watching the videos of the destruction.

- This topic is incredibly expansive. If you would like more information on the topic regarding non-Western art/artifacts, events from the more recent past (e.g. the role of Napoleon or Hitler in the destruction of cultural heritage), or additional discussions, please explore Smarthistory's At-Risk Cultural Heritage Series (ARCHES). ↵

- The “Iconoclastic Controversy” over religious images was a defining moment in the history of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. Centered in Byzantium’s capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) from the 700s–843, imperial and Church authorities debated whether religious images should be used in Christian worship or banned. ↵

- In addition to the UNESCO repatriation protocols, the United States specifically has federal laws in place regarding the repatriation and disposition of certain Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony in the form of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). ↵

in the original place.

the social belief in the importance of the destruction of icons and other images or monuments, most frequently for religious or political reasons.

one who venerates icons and defends their devotional use.

looting carried out to supplement meagre incomes

from scratch, from the beginning

the most important reason or purpose for someone or something's existence.

(of a work of art or architecture) executed in an earlier or outdated style.

the process of returning a thing or a person to its country of origin or citizenship.

the restoration of something to its original state.

lacking provenance; the place of origin or earliest known history of something.