6

Sharah Meservy and Alex Bond

It is clearer than ever that no community in the U.S. is immune to the insidious effects of racial inequality. As the Salt Lake region becomes increasingly racially diverse, identifying and confronting racial injustice must be a priority in both the private and public sectors. One concern that should not be overlooked is how inequality is reflected in local landscapes. In the words of Banzhaf and colleagues (2019): “Because public goods are part of households’ real income, the distribution of environmental amenities is part of the overall landscape of inequality.” Are resources like clean air, unpolluted water, or access to public green spaces distributed equally? Do some demographic groups bear a heavier burden than others when it comes to exposure to potentially harmful pollutants?

In this study, we investigate environmental justice in Salt Lake County by studying the distribution of facilities that generate large quantities of hazardous waste (which we refer to as “large quantity generators”) and hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities (hereafter simply “hazardous waste facilities”). In particular, we examine whether Salt Lake County large quantity generators and hazardous waste facilities are more likely to be located in communities of color and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. To do so, we examine community demographics within a three-mile radius of 46 facilities identified in Salt Lake County by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) using U.S. Census data.

Based on our analysis of these data, there seems to be a clear correlation between the location of hazardous waste facilities in Salt Lake County and both the proportion of “minority” residents and people living below the poverty level. With the exception of one site not located near a residential area, all hazardous waste facilities were in communities with above average proportions of household numbers living below the poverty level, and 72% of the sites were in communities with above average proportions of minority residents.

Literature Review

Environmental justice, as defined by the EPA (n.d.) is “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Banzhaf et al. (2019) trace the beginning of the environmental justice movement to a 1978 case in North Carolina. After identifying two potential landfill spots for hazardous waste, the state chose the less suitable site that nonetheless posed less “red tape” to overcome. The chosen site was in a county whose population was 60% Black with 25% of households living below the poverty line, while the corresponding demographics around the other site were 27% and 6%, respectively. The resulting protests garnered attention from civil rights groups, birthing a movement that has led to decades of research, although arguably not much (or enough) by way of improvements.

Informative to the current study, the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice released a landmark 1987 study entitled “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States,” reporting that people of color and from low socioeconomic status were disproportionately impacted by hazardous waste facilities, and, according to the study’s findings, race was the primary predictor of where toxic waste is located in the U.S. The researchers repeated the study in 2007 and found virtually nothing had improved in the ensuing twenty years (Bullard et al., 2007). Analyses of environmental lawsuits have similarly revealed a racial divide in the action taken to clean up toxic waste sites and punish polluters (Lavelle and Coyle, 1992). Penalties were significantly harsher and issued more quickly against firms violating regulations in majority white areas than they were in nonwhite areas. Study authors (controversially) suggested this divide to be a result of “neglect, not intent” attributing the racist imbalance to “hundreds of seemingly race-neutral decisions in the science and politics of environmental enforcement” (Lavelle and Coyle, 1992).

Several studies have disputed the conclusion that race is the driving cause of toxic waste facility siting. For example, Anderton, Anderson, Oakes, and Fraser (1994; as cited in Banzhaf et al., 2019) found no correlation between race and toxic waste locations after controlling for other socioeconomic factors, pointing instead to the manufacturing labor market as the weightiest predictor. Gray et al. (2010) examined the correlation between environmental regulation of industrial plants and the demographics of nearby residents, finding less regulation in low-income communities, but not necessarily in communities with high numbers of minorities. Instead, they found a significant correlation between regulations and the average voter turnout of a community.

In response, Banzhaf et al. (2019) posit four possible mechanisms that could create these disparate impacts: (1) disparate siting by firms, (2) households coming to the nuisance, (3) Coasean bargaining, and (4) discriminatory politics and/or enforcement. “Disparate siting” is the idea that firms choose to locate their hazardous waste facilities in areas with a relatively large racial minority population, either for racist, economic, or regulatory reasons. If we think of the theory of disparate siting as a chicken-before-egg process, then “coming to the nuisance” would be its egg-before-chicken counterpart. Coming to the nuisance refers to a process where the establishment of hazard waste facilities drives away residents who can afford to live in more desirable areas, resulting in lower housing prices which then attract poorer households. The third mechanism suggested by Banzhaf et al., Coasean bargaining, takes its name from economist Ronald Coase who wrote (1960, quoted in Banzhaf et al., 2019), “[t]hrough negotiation, the right to pollute (or to be spared pollution) will end up in the hands of the individuals or firms who value it most, and all parties will be appropriately compensated for any nuisance or foregone profits they consequently bear.” In other words, Coasean bargaining is the idea that communities accept hazardous waste facilities in their neighborhoods because the benefits outweigh the costs.

The final mechanism which could influence the siting of facilities is the political economy. This encompasses factors such as legislation, local enforcement of regulation, or the potential for collective action by citizens. In the North Carolina case referenced above, the site that was rejected for the landfill was publicly owned and local residents had a voice in any decision about how the land was used, while the site ultimately chosen was “privately owned and near a town with no mayor or city council” (ibid.). So, in this case, it appears that the most influential factor in the siting decision was likely political. While our study focuses only on indicators that environmental justice exists in Salt Lake county and does not extend to exploring the causes behind it, Banzhaf et al.’s research provides essential context for the discussion of environmental justice and a useful framework for future research.

The Empirical Context: An Increasingly Diverse Utah

Utah’s population, while predominantly white, is becoming increasingly diverse. From 1850 through 1960, 98% or more of the population identified as white and non-Hispanic. By 1990 the proportion had dropped to 94%, and then to 85% by 2000 (Perlich, 2002). The most recent estimates show that in 2019 non-Hispanic whites made up 77.8% of Utah’s total population (Kem C. Gardner Institute, 2020). As Utah’s population becomes increasingly diverse, we expect environmental justice to become of even greater concern. Most research relevant to matters of environmental inequities and injustices focuses on air quality. In Salt Lake County, for example, public schools serving economically disadvantaged students experience disproportionate exposure to air pollution (Mullin et al, 2020). Within Salt Lake City specifically, being Mormon and being white are the two strongest predictors of protection from air pollution (Collins and Grineski, 2019). One study in Cache county found a correlation between minority population density and lower quality public parks (Chen et al., 2019). However, in the course of this research, we turned up no studies that looked specifically at hazardous waste sites in Salt Lake County.

Data and Methods

Our study uses quantitative analysis of data obtained from the EPA’s Environmental Justice screening tool, EJSCREEN. First, we used the mapper tool (found at https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/) to map out the location of every large quantity generator and hazardous waste facility in Salt Lake County. With the same tool, we layered population demographics pulled from 2013-2017 American Community Survey data. We noted the locations of large quantity generators/hazardous waste facilities in relation to the surrounding communities’ percent racial minorities, defined as individuals identifying as nonwhite, and percent living below the poverty level. Finally, we used the EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online tool (ECHO) to access 2010 U.S. census data on the percent of racial minority residents in a 3-mile radius around each facility.[1]

Findings

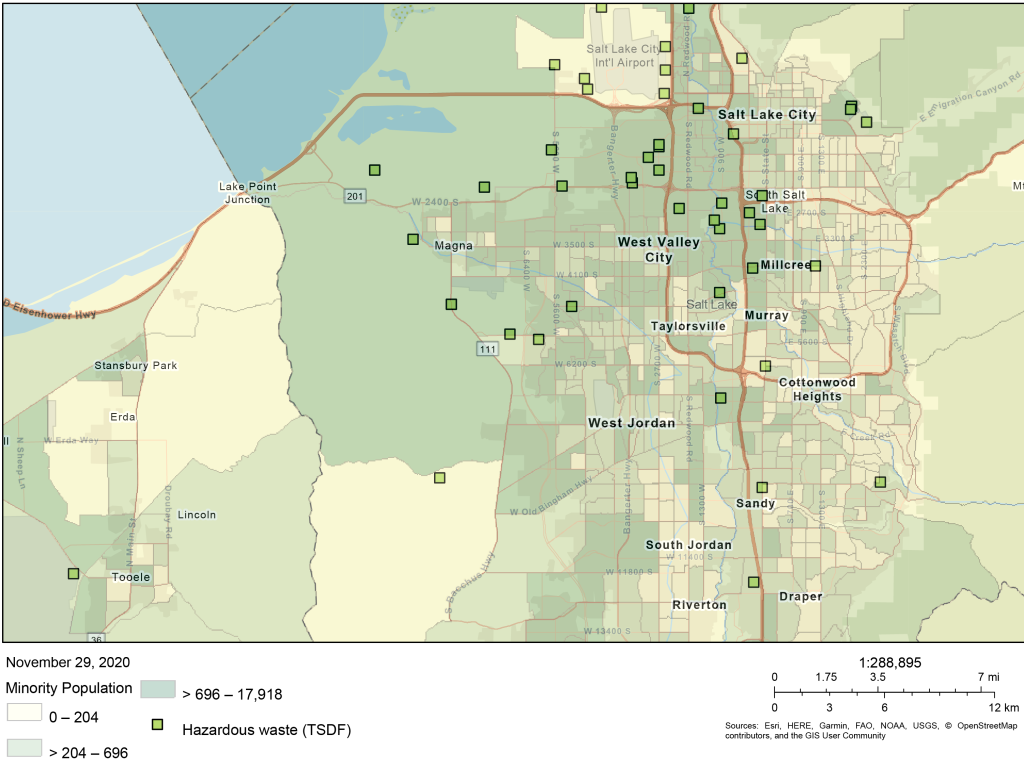

Our initial visual review of the EJSCREEN Tool’s data supported our expectations, based on the cited literature, about the location of hazardous waste facilities in relation to local minority and below-poverty residents. As seen in Figure 1, the majority of large quantity generators and hazardous waste facilities (indicated by small green squares on the map), are located in the northwest area of Salt Lake County, with clusters in South Salt Lake and to the north of West Valley City. Their placement coincides with higher density of racial minority residents, identified by dark green shading. Few of the hazardous waste facilities are located in areas with comparatively low levels of minorities.

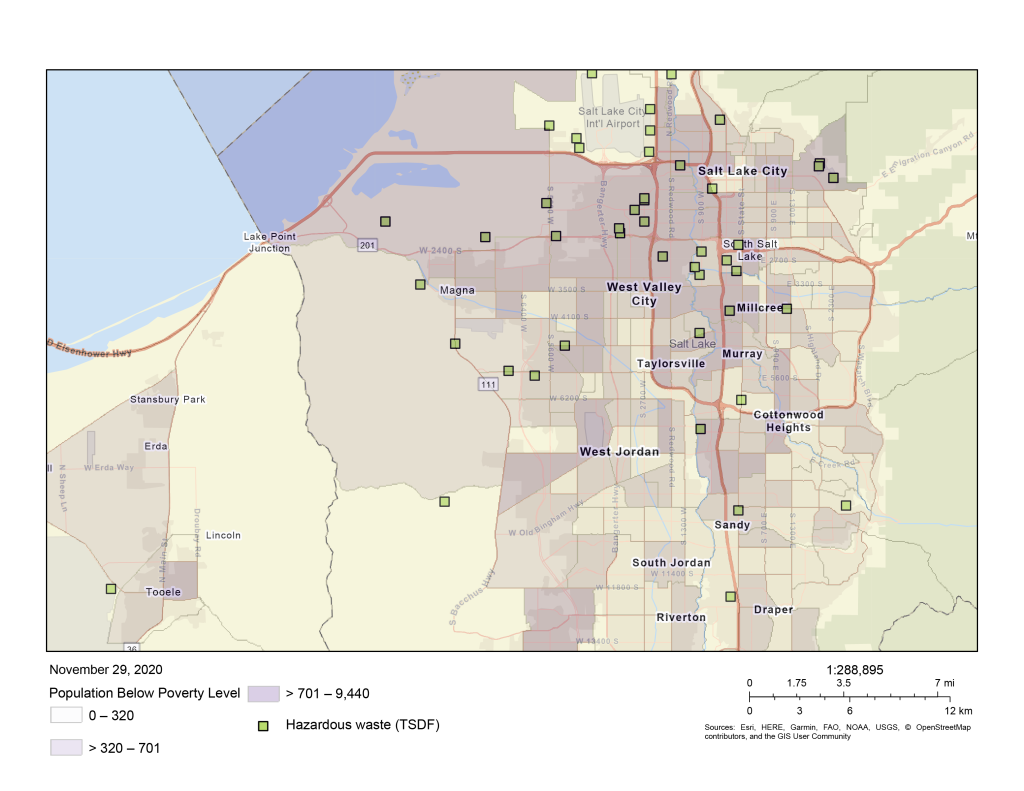

Next, Figure 2 shows the same area, but indicates the distribution of Salt Lake County residents who are below the federal poverty level. Upon initial examination (and perhaps unsurprisingly), it seems that the distribution of residents living below the poverty level matches the general distribution of minority residents, with the eastern side of the county being predominantly white and also above the poverty level. A notable difference in the correlation between hazardous waste sites and prevalence of residents living below poverty level is the cluster of facilities in South Salt Lake – an area with seemingly fewer residents living below the poverty level.

To further investigate the relationship between hazardous waste facility siting decisions and the geographic distribution of residents living in poverty and racial minority residents, we pulled demographic data for a 3-mile radius around each of the hazardous waste sites from the EPA’s ECHO database. Of the 48 sites identified by the EPA, only two sites did not have any available demographic data (those sites were excluded from the analysis). Of the remaining 46 sites, one was located in an unpopulated area. We order the findings, presented in Table 1 below, according to the percent of the population surrounding each site that lives below the federal poverty level.

| Site # | % Below Poverty | % Minority | Site # (cont’d) | % Below Poverty (cont’d) | % Minority (cont’d) |

| Site 1 | 0% | 0% | Site 24 | 35% | 68% |

| Site 2 | 14% | 11% | Site 25 | 36% | 31% |

| Site 3 | 15% | 13% | Site 26 | 36% | 71% |

| Site 4 | 18% | 55% | Site 27 | 38% | 22% |

| Site 5 | 21% | 47% | Site 28 | 39% | 34% |

| Site 6 | 24% | 20% | Site 29 | 40% | 34% |

| Site 7 | 27% | 50% | Site 30 | 40% | 52% |

| Site 8 | 28% | 24% | Site 31 | 42% | 39% |

| Site 9 | 28% | 22% | Site 32 | 44% | 45% |

| Site 10 | 29% | 21% | Site 33 | 45% | 53% |

| Site 11 | 29% | 17% | Site 34 | 45% | 57% |

| Site 12 | 29% | 17% | Site 35 | 45% | 45% |

| Site 13 | 30% | 45% | Site 36 | 45% | 45% |

| Site 14 | 30% | 38% | Site 37 | 46% | 47% |

| Site 15 | 31% | 18% | Site 38 | 46% | 59% |

| Site 16 | 31% | 18% | Site 39 | 48% | 48% |

| Site 17 | 31% | 39% | Site 40 | 48% | 28% |

| Site 18 | 31% | 40% | Site 41 | 48% | 64% |

| Site 19 | 32% | 40% | Site 42 | 52% | 63% |

| Site 20 | 34% | 34% | Site 43 | 52% | 63% |

| Site 21 | 34% | 34% | Site 44 | 53% | 65% |

| Site 22 | 34% | 34% | Site 45 | 53% | 66% |

| Site 23 | 35% | 33% | Site 46 | 53% | 67% |

We use average county-level statistics to anchor our analysis. According to Census data, nine percent of Salt Lake County residents lived below the federal poverty level in 2010, and 29.7% were non-white. As indicated in Table 1, this means that every large quantity generator and hazardous waste facility in Salt Lake County is located in an area with above average levels of poverty, with the single exception of one site that is not located within three miles of a residential area. In the table, we marked all sites surrounded by an above average percent of nonwhite residents in red. The findings suggest a strong correlation between the siting of hazardous waste and communities of (greater) color, with almost 72% of hazardous waste sites being in areas with above average proportions of minority residents.

Discussion

We set out to identify whether hazardous waste facilities in Salt Lake county are more likely to be located in communities of color and/or socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. Of the 45 sites we studied that were located in populated areas, all were located in areas where the percent of residents living below the poverty level outpaced the county average, and 33 out of 45 were located in areas where the proportion of nonwhite residents was above the countywide average. These findings align with the literature demonstrating that people of color and low socioeconomic status are disproportionately impacted by hazardous waste facilities. However, while much prior research suggests race is the primary indicator of toxic waste siting, our descriptive analysis indicates that the prevalence of poverty may be as, if not more, important in Salt Lake County.

Ours was a descriptive analysis of secondary data, with some noteworthy limitations. Perhaps most notably, the research design precludes us from identifying the mechanisms of seemingly discriminatory hazardous waste siting in Salt Lake County. First, the scope of our study is too narrow to assess whether or not the manufacturing labor market is a significant impact on siting decisions (as put forth by Anderton et al.), but one could argue that Salt Lake County’s relatively small geographic size may render that factor less relevant, as a commute across the valley may not be as prohibitive for many workers. Turning to the factor identified by Banzhaf et al. (2019), further research would be needed to determine whether firms or “the market” are compensating the communities surrounding their hazardous waste facilities (Coasean bargaining) or whether discriminatory political factors are to blame.

An examination of when the facilities were built compared to when the residential areas around them were developed might give us clues to whether disparate siting by firms is the primary issue, or if residents settled in those areas later due to economic convenience. Considering that hazardous waste facilities are more commonly found on the more recently developed west side of the valley rather than in the older neighborhoods of the east side, it would not be unreasonable to suggest that they are neither cause nor effect of temporal distribution. Rather, higher real estate values on the east side of the valley could be attributed to proximity to the downtown area, the University of Utah, and/or popular ski resorts in the Wasatch mountains. Since these amenities are not important for the purposes industrial firms, it makes sense that they would be more likely to establish facilities in areas where undeveloped land is both cheaper and more readily available – recalling the history of redlining and wealth inequities as a perpetual contributor to racist and discriminatory circumstances and outcomes (Rothstein, 2017).

The above limitations notwithstanding, our microstudy highlights the fact that being a minority and/or living in poverty in Salt Lake County results in a higher chance of living near hazardous waste facilities, and recognition of current and historic injustice is an important first step towards building a more just and equitable future. As Salt Lake County continues to grow and develop, we hope that legislators and municipal governments will give careful consideration to environmental justice, especially selecting sites for amenities (e.g. affordable housing) and in allowing the siting of disamenities (e.g. hazardous waste facilities).

Conclusion

We sought to discover whether large quantity generators and hazardous waste facilities in Salt Lake County are more likely to be located in communities of color and in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. We utilized the EPA’s environmental screening tool EJSCREEN to visualize the locations of hazardous waste facilities and compare them against demographic data. We then examined the demographic data in a 3-mile radius around each facility. With the exception of two sites lacking data and one located in an unpopulated area, all sites were located in areas where the proportion of people living below the poverty level was above the county average and almost three in four were sited in communities where the proportion of minority residents was over the county average.

Our findings are evidence that environmental injustice exists in Salt Lake County. While more research is needed to understand the extent of the problem and the mechanisms behind it, it is clear that an issue exists and it needs to be addressed. We find it unacceptable that any member of our society be at higher risk of exposure to hazardous waste or its byproducts because of the color of their skin and we must ensure that all residents have access to clean and equitable living conditions, regardless of their financial condition. Until this is a reality, environmental justice will not exist in Salt Lake County.

References

Baca Zinn, M. (1979). Field research in minority communities: Ethical, methodological, and political observations by and insider. Social Problems, 27(2).

Banzhaf, S., Ma, L., & Timmins, C. (2019). Environmental justice: The economics of race, place, and pollution. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(1), 185-208.

Bullard, R., Mohai, P., Saha, R., and Wright, B. (2007). Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty 1987-2007: A Report Prepared for the United Church of Christ Justice & Witness Ministries. United Church of Christ (UCC). Retrieved from http://www.ucc.org/environmental-ministries_toxic-waste-20.

Chen, S., Sleipness, O. R., Christensen, K. M., Feldon, D., & Xu, Y. (2019). Environmental justice and park quality in an intermountain west gateway community: Assessing the spatial autocorrelation. Landscape Ecology, 34(10), 2323-2335.

Collins, T. W., & Grineski, S. E. (2019). Environmental Injustice and Religion: Outdoor Air Pollution Disparities in Metropolitan Salt Lake City, Utah. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109(5), 1597-1617.

EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool (Version 2019). Retrieved September 27, 2020, from https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/

Fujii, L. A. (2012). Research ethics 101: Dilemmas and responsibilities. PS: Political Science & Politics, 45(04), 717-723.

Gray, W.B., Shabegian, R. J., & Wolverton, A. (2010). Environmental Justice: Do Poor and Minority Populations Face More Hazards? (NCEE Working Paper No. 10-10). Retrieved from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website: https://www.epa.gov/environmental-economics/working-paper-environmental-justice-do-poor-and-minority-populations-face

Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. (2020). Utah State and County Annual Population Estimates by Single-Year of Age, Sex, and Race/Ethnicity: 2010-2019 [Fact sheet]. University of Utah. Retrieved from https://gardner.utah.edu/wp-content/uploads/PopEst-AgeSexRace-FS-Aug2020.pdf

Lavelle, M. & Coyle, M. (1992) Unequal Protection: The Racial Divide In Environmental Law. The National Law Journal, 15(3), S1-S2

Mullen, C., Grineski, S., Collins, T., Xing, W., Whitaker, R., Sayahi, T., Kelly, K. (2020). Patterns of distributive environmental inequity under different PM2.5 air pollution scenarios for Salt Lake County public schools. Environmental Research, 186, 109543.

Perlich, P. S. (2002). Utah Minorities : The Story Told by 150 years of Census Data. University of Utah Bureau of Economic Business Research

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing.

- Ideally, we would use more recent and concurrent data, since there is likely to be some difference in the numbers from the 2010 U.S. Census and the American Community Survey data, but unfortunately 2020 U.S. census results were not yet available at the time of this writing. ↵