2

Anna Cushing; Alison Cañar; and Russell Facer

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been far-reaching and destructive to both public health and the world economy. Although many of the impacts stemming from COVID-19 are devastating, some effects have arguably led to positive new trends. An example of this is the increased use of teleworking. Prior to the pandemic, many employers remained steeped in traditional working styles and lacked the desire or the capacity to allow their employees to telework (Mahler, 2012). Crisis often breeds innovation, and in this case, many companies and governments have been forced to either cease work or allow their employees to work from home. This pandemic has brought a new opportunity for private and public sector organizations to evaluate the effects of teleworking on their employees.

The purpose of this study is to understand the effects of teleworking on public sector employees. Using an interpretivist approach, we used interviews to understand employees’ perceptions of their morale and productivity since switching to telework during the pandemic. Although the methodology is limited in its generalizability, our analysis of interview themes offers a greater understanding of the potential for future telework in these organizations, with both potential benefits and drawbacks. This is important for public administrators, who could more successfully manage their organizations by maximizing the benefits and minimizing the drawbacks of telework going forward.

Literature Review

While the COVID-19 pandemic creates a new impetus for organizations to experiment with teleworking models, previous research has studied potential benefits of teleworking to society, organizations, and employees, as well as potential drawbacks. Such benefits include reduced traffic and pollution (Shia & Monroe, 2006); increased work-life balance (Morganson et al., 2010; Kwon & Jeon, 2018); and reduced turnover (Chung & Van Der Horst, 2017; Kossek et al., 2016). Identified drawback include incidents of depression (Morganson et al., 2010); stress from lack of clearly defined work hours (Morganson et al., 2010); and difficulty in monitoring employee performance (Kwon & Jeon, 2018). As an additional consideration, many essential jobs are not suitable for telework (Dey et al., 2020). Opportunities for additional research include exploring best practices for maximizing the benefits of telework flexibility while minimizing the negative impacts of the reduced face-to-face interaction.

Eliminating or reducing commutes was a sought-after societal benefit that inspired an early wave of teleworking across the country. Research on telework gained popularity after the 1990 passage of the Clean Air Act encouraged businesses to offer telework opportunities as a method for reducing pollution and roadway congestion (Shia & Monroe, 2006). Over time, telework rationales began to focus more on making work more enjoyable for employees, thereby increasing their dedication to employers (Morganson et al., 2010). Telework opportunities in the public sector were bolstered by the 2010 Telework Enhancement Act, which required federal agencies to develop telework programs for government employees (Kwon & Jeon, 2018). Telework was designed to make government work more attractive for new generations of workers who highly value work-life balance and have more non-traditional family structures that make employer support of family life more critical (Kwon & Jeon, 2018).

Some factors that research has found to affect an employee’s satisfaction with telework include family structure, gender, and work schedule. Studies have found employees with children at home report the most satisfaction with telework opportunities, but women did not benefit as much as men (Shia & Monroe, 2006). In addition, part-time employees and employees who work remotely a moderate amount of time report higher morale than peers who worked full-time on-site or full-time off-site (Morganson et al., 2010).

Several studies, in particular Chung & Van Der Horst (2017), focus on exploring how teleworking impacts women’s employment post-childbirth, hypothesizing that women are more likely to continue their work and not reduce their work hours after childbirth if they can choose where to work (home vs office). Kossek et al. (2016), explore telecommuting and perceptions of psychological job control, which they defined as “the degree to which an individual perceives that they can control where, when, and how they work” (Kossek, p.350). They found that employees who perceived greater psychological control had higher job satisfaction, less turnover, and better work-life balance.

While teleworking has been found to provide more balance for employees, it can also lead them to feel disconnected from the office and even depressed (Morganson et al., 2010). Additionally, teleworking can increase stress in high-demand positions where work feels inescapable (Morganson et al., 2010). It also poses downsides for employers in increasing the difficulty of monitoring employee’s performance (Kwon & Jeon, 2018).

Opportunities for teleworking vary by industry. Research conducted by Dey et al. (2020) found that the industries with the highest capacity for telework are finance, information, and professional and business services, each with over 70% of employees able to telework. Public administration ranked fourth, with 57% of employees able to telework. Industries with low levels of teleworking capacity included agriculture, leisure and hospitality, construction, and retail; each with below 30% of employees able to telework. Demographically, they found education creates the largest divide between those who can work from home and those who cannot. Of workers with a Bachelor’s degree or higher, about 68% could telework compared to only 25% of workers without a college degree. Inequalities of teleworking availability were also found across races: White, 49%; Black, 40%; and Hispanic, 29%. Overall, about 44% of the workforce has a job that can be performed remotely (Dey et al. 2020). Although many jobs are not suitable for telework, the relatively high availability of telework within the field of public administration makes it a topic of interest to industry professionals and scholars.

Research Design

We use in-depth interviews to collect primary qualitative data regarding how public employees perceive teleworking. We use an interpretivist epistemic approach and narrative analysis of interview data – in other words, analysis of a text based on the researcher’s own worldview, values, culture, and experience (Riccucci, 2010, pg.1) – to draw our conclusions. Our interviewees reflect a convenience sample strategy, as we interviewed a small group of people we had existing relationships with. With this in mind, the study was more exploratory in nature, without the intent to generalize findings to a larger population. From a practical perspective, just because one, some, or even the majority of our interviewees say they feel a certain way does not mean that managers should be too hasty to implement changes that may not be in their employees’ best interests. We interviewed people with whom we either work or are acquainted with from public organizations in and around Salt Lake City. The characteristics of our interviewees are presented in Table 1, immediately below.

| Pseudonym | Job characteristics | Home and family characteristics |

| Amy | Teachers’ union director | Room for home office; married; no children |

| Cassie | Office administrator | Small apartment with a roommate; no children |

| Christine | Public education employee | Long commute from home to office; room for home office; living with parents; no children |

| Jessica | Public relations coordinator | Room for home office; married; mother of toddler |

| Kate | Public education employee | Apartment with no room for an office; mother of toddler |

| Mark | Staff officer in military organization | Room for home office; father of two teenagers and one adult |

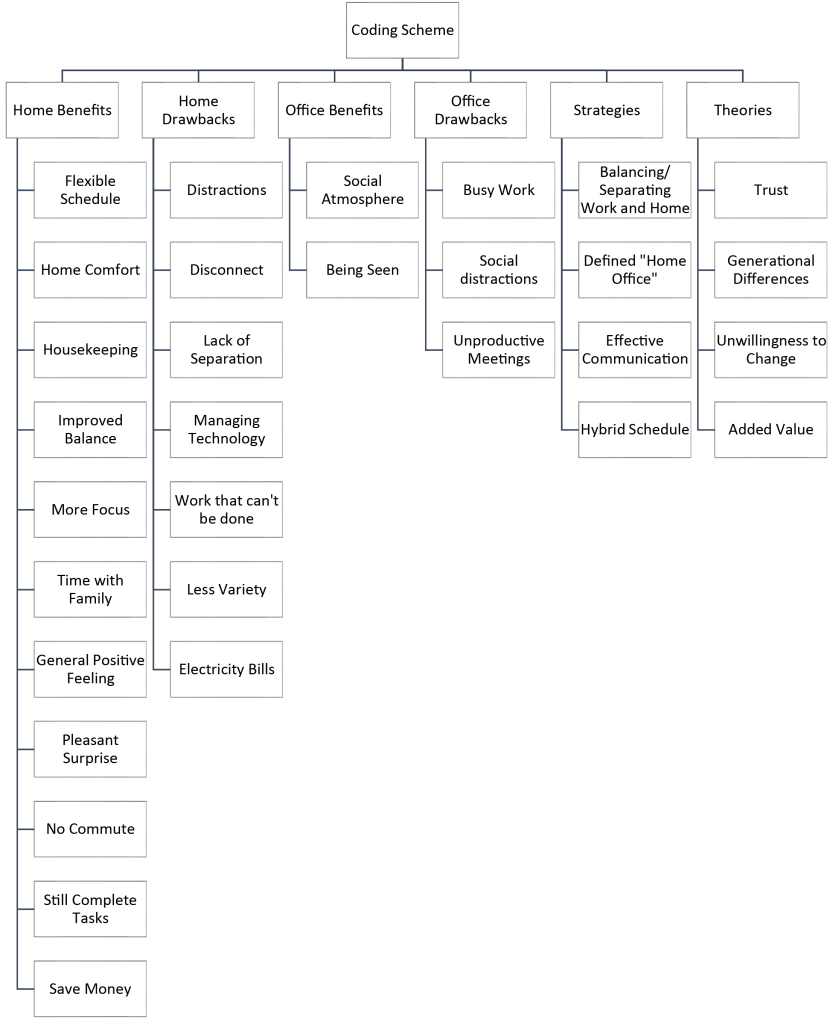

Our data were collected through in-person and video conference interviews, following were semi-structured and open-ended questions. Interviews followed standard questions, although some room for adjustments was allowed to gain a deeper understanding of employees’ perceptions and experiences while working remotely. Six in-depth, 30-minute interviews were conducted and recorded. A free (lite) version of the QDA Miner software was used to transcribe and code the data. In an inductive analysis, the resulting data were divided into 6 themes: Home Positives, Home Negatives, Office Positives, Office Negatives, Strategies, and Theories. Once we identified additional underlying common patterns and themes, each interview was coded as explained further in our findings and illustrated in Figure 1.

Ethical Considerations

Because we asked about employees’ job performance, we needed to be mindful of how their answers could affect them professionally; discussing potential dips in productivity or morale could be viewed negatively by their current or future employers. To encourage more candid answers and mitigate potential harms, we determined it was best for us to provide anonymity to our interviewees. We thus use pseudonyms to protect our interviewees (see Table 1).

We also obtained informed consent from our participants and did not pressure anyone who felt uncomfortable to participate in our study. This was especially important with the convenience sample that we conducted in order to ensure that our personal or professional relationships did not pressure potential interviewees to participate if they felt uncomfortable.

Finally, because of the political nature of some aspects of public employment and to avoid public criticism of a particular agency for their employment practices we describe only the type of work interviewees performed without stating which agency the respondent is employed by. This also added an extra layer of anonymity for the participants. With these practices implemented in our study, we felt the the ethical concerns of our study were effectively mitigated.

Findings

Our findings are presented in the following sections: benefits of working from home, drawbacks of working from home, benefits and drawbacks of office work, strategies and best practices of telework, and theories regarding the future of telework. Each section provides summaries and analysis of the six interviewees’ perceptions of telework. The findings aim to address the effects of teleworking on public sector employees and to identify common trends. Additionally, this section hypothesizes about the future of teleworking and the best practices of teleworking as perceived by public sector workers.

Benefits of Working from Home

The analysis of our interviews showed that five of the six interviewees felt that their productivity and morale went up significantly while working from home and many defined their telecommuting experience as very positive. One of the interviewees (“Amy”) indicated that at first she felt anxious about working from home because she did not even think that it would be possible. However, once she adjusted to the situation and improved her home working conditions (such as buying a second monitor), her worries turned into an overall positive experience. She felt that she is now more productive and, for example, could have meetings back-to-back without wasting time moving from one place to another.

Another interviewee (“Kate”) explained that her productivity went up because now her time is more flexible and she can either work early in the morning or late at night to complete all of her work-related tasks. Interviewees who indicated that their productivity went up also tied it to their morale level. “Christine” pointed out that her morale definitely went up because telecommuting allowed her to have a more healthy lifestyle and pay attention to her personal life and needs. “Mark” felt that now he can use his time more productively and his morale increased because working from home made him feel even better psychologically. He thought that working from home delivers comfort that you might not necessarily have in the office.

It is worth noting that “Cassie” indicated that working from home affected her morale in both ways: negatively and positively. On the one hand, she noted that she feels disconnected from the world while teleworking, but on the other hand, it is nice not to have distractions and be more focused. As for productivity, she felt it went down because the nature of her work requires her to be in the office.

Participants commonly shared two positive aspects of working from home: their ability to spend more time with family increased and their work-life balance improved significantly. All six interviewees mentioned that telecommuting allowed them to have a more flexible schedule, and hence to have a “more purposeful life”. For example, “Jessica” indicated that a flexible schedule at work allowed her to have more time for her personal needs :

Oh my gosh–I love it! It’s not without challenges, but I love it. I get to maintain my own schedule. And so that does allow me flexibility. So…before… I do not like… you have to get ready for the day, and I wouldn’t make it to the office until like 8:30 or 9:00. But at home, if I’m awake at 6:00 or 6:30–boom. Put on my robe, come in, pound out a few hours before my kid wakes up. Then I can stop a little bit and have breakfast with him, my husband takes him, pound out a few more hours, take lunch with my family. There’s just a lot of flexibility in that way.

Kate shared the same thought as Jessica. She thought that a flexible schedule allowed her to spend more time with her baby. Kate pointed out that before her office switched to remote work she felt guilty for leaving her baby at home while working in the office the whole day. Now she can work and take care of her baby because the flexible schedule allowed her to maintain a work-life balance. Cassie echoed Jessica’s and Kate’s perceptions, indicating that because of the flexible schedule it is easier for her now to focus more on her personal life.

The majority of interviewees thought that saving time on their commute makes them more efficient and productive. Christine singled out an absence of commute as the most important positive for her while teleworking. She said that commuting two hours daily to and from work had a huge negative psychological and physical impact on her. Christine felt that teleworking made her job more enjoyable because now she does not need to worry about planning her commute daily. Other interviewees perceived that saving time on their commute allowed them to have time for other activities such as exercise or housekeeping.

One interviewee pointed out that telecommuting allowed her to save money on childcare. She indicated that if she works from the office she breaks even and it turns out that she works just to pay for her childcare. Overall, respondents found more positives than negatives working from home. Moreover, based on their teleworking experience five of the six interviewees indicated that they would choose to continue working from home or explore a hybrid schedule if such an opportunity presented itself after the COVID-19 pandemic has ended.

Drawbacks of Working from Home

Although the majority of respondents described an overall positive experience working from home, each respondent identified drawbacks associated with telework. Some of these drawbacks can have major effects on the morale and productivity of employees, while others are simply annoyances. Major drawbacks ranged from frustrations with technology and the distractions of home to the struggles communicating with colleagues. Minor drawbacks of working from home included paying more for electricity, a lack of variety, and less movement. It seems that despite the drawbacks, the majority of respondents would rather deal with these negative consequences than go back to working in the office full time.

One of the most important difficulties identified by most of the respondents was distractions that are found at home and how they affect productivity. Having children at home (especially toddlers) led to a different perception of productivity than would normally be seen in the office. This perception was held by both parents and childless interviewees. Jessica explained her experience having a child and working:

I can’t work – I should say this, when I am in charge of him, like it’s my turn – I can’t work. There is no way. When I did that one time, he shut himself in a glass shower and was screaming and couldn’t get out. And that was so sad. It was – it was – ahh! – so sad. I felt awful, and then he – the last time it happened, I had a webinar, and he drew on our carpet with crayon. I did not know that crayon would transfer onto carpet, but it does. So it – it was, like, red – it was so awful. So, someone else has to be watching him for me to work.

Jessica was not alone in this experience, as Kate also described struggles when she was in charge of her baby. Three of the respondents who did not have children also perceived a difference in productivity or a difference in schedule with those who had young children at home. Children were not the only distraction. For example, Mark explained the draw for some of his coworkers to mow the lawn or other chores instead of work. Christine stated that she struggled with looking at her personal social media and email more at home, where she was not being watched.

Another difficulty faced by those working from home was a disconnect from both supervisors and coworkers. The disconnect had different impacts, ranging from a lack of social interaction to having a hard time communicating the needs of the organization between members of staff. Lack of social interaction impacts varied between people with different personalities. For Cassie, it was really difficult to not have daily interactions and she stated that this had a negative effect on her morale. Mark, on the other hand, stated that it was a problem for his coworkers, but as a self-identified introvert he had no problem with simply emailing or conducting zoom meetings to fulfill his social needs. While interaction with others had effects on morale, it also had effects on organizations’ productivities. Three of the respondents expressed difficulties getting information regarding their responsibilities from supervisors. Others felt that their coworkers were not able to share information, leading to a lack of team cohesion.

Part of the communication struggle came from managing technology. Four of the respondents noted that while technology was not an issue for them, they could see others having a difficult time working through the changes. Jessica perceived a generational difference when it came to maintaining remote productivity. She noted that she has had to help other staff in her office to understand how to use necessary technology. Our oldest respondent (Mark) stated that he had coworkers who struggled, but because he has been working remotely for another part-time job for nearly ten years, his transition to remote work was seamless.

All six respondents explained that there are some jobs that simply cannot be done from home. During the COVID-19 pandemic some people were restricted from entering their offices. Most explained that if there was an issue with getting things done from home, they or their coworkers were allowed to have a hybrid schedule – where they could go in to do the work that could only be done in the office. This would be a major factor going forward. Cassie explained: “I just think that with my role, it is more of an office job, so it has been hard to be as productive because a lot of the things you would be doing, I am not able to do from home.”

Benefits and Drawbacks of Office Work

Although we asked no questions directly regarding the benefits and drawbacks of office work, many respondents used them to illustrate the differences of working from home. Some of the negative aspects respondents identified included social distractions, unproductive meetings, and busywork. Jessica, who was quoted above explaining the challenges of having a child at home, said: “And so [at home] I’m able to really just focus and hustle. So, shockingly, with a toddler at home, I have fewer distractions than I do in an office with grown people.” This idea was echoed by Cassie and Christine, who both explained the problems that office socializing created for their productivity.

One of the office benefits that some of the respondents felt were missing at home was a social atmosphere. As was described before, being surrounded by others at work can boost employee mood and increase morale. It also helps to build an aspect of teamwork and friendship that can increase productivity in team environments. An aspect that was only described by Jessica but is nonetheless important was “being seen.” Not only does “being seen” by others in the workplace impact employee productivity, but it can have an impact on career trajectories. Jessica was interested to see what would happen to employees who remain teleworking long-term and felt that showing her face to her managers was an important aspect of career mobility.

Strategies & Best Practices for Telework

Throughout our interviews, respondents shared several techniques they use to mitigate the downsides of working from home, such as an undesired blurring between work and home hours and difficulty staying engaged and socially connected with colleagues. One of the key strategies, mentioned by two-thirds of our respondents, was having a clearly defined home office space. Cassie, our respondent with the least enthusiasm about teleworking, lives in a small apartment where she is not able to set up an office: “When I am at work, I am able to have a desk and files so it is a lot more organized whereas at home it is all just digital.” In contrast, Amy – who was initially skeptical about teleworking – came to enjoy it once she set up a defined home office space. She also learned to change in and out of “work clothes” to draw a clearer distinction between work and relaxation hours:

For me after those first couple of weeks, I found I needed to get up; I needed to shower; I needed to dress in work clothes. Like, I couldn’t just put on something nice on the top and have sweats on the bottom; I couldn’t do it because I didn’t feel like I was working. So I continued to dress for work so that when I was done, I could… leave my little bedroom office and go and change my clothes, and I was home.

In contrast, another respondent, Jessica, enjoys the ease of being able to work in her robe and eliminate time spent getting ready for the day. But, she also emphasized the importance of having a home office where she has fewer distraction:

when it was shut down, there were still people who chose to work in the office—I don’t think they had an office space. …I already had an office at home. My husband has an office too, so we don’t have to share… so it wasn’t a hard transition where I think some of my other coworkers couldn’t cope with that.

Another commonly discussed strategy was maintaining frequent communication to keep employees and supervisors up-to-speed with developments across their teams. Amy mentioned how she and her colleague frequently sent quick messages to address how to handle problems as they arise:

Communication is really important as far as checking in and making sure that people know what they’re doing… like, if emails came in addressed to both of us, it would be a quick text: “are you gonna take that one; am I going to take that one?” You know, kind of thing—just trying to coordinate the work.

As a counterexample, while Jessica was able to stay in communication with many of her colleagues with quick check-ins and updates, she expressed frustration about her supervisor not being more communicative and letting the challenges of digital interfacing stand in the way of maintaining group cohesion: “Do I want to do a Zoom staff meeting? No. But do I think it would be beneficial for all of us to get on and see each other’s faces and talk about what’s going on? Absolutely.”

Several respondents also mentioned a hybrid schedule as a means of enjoying the comfort of working from home at least part-time while still utilizing occasional time in the office for in-person discussions and completing tasks that can’t be done remotely, such as checking the office mail. Some respondents expressed that 80-90% of their work could be done from home, while others proposed a 50/50 balance. Only one respondent would prefer to do all of her work from the office.

Theories Regarding the Future of Telework

When asked about what factors might make teleworking more or less appealing to organizations and the individuals that work for them, generational differences and accompanying perceptions towards tradition were common themes. Jessica described what she perceives as generational differences between herself and others at her office:

I do wonder a little bit if it is a little of my age just because… technically I’m a millennial… one of the things is having a flexibility with work. …Whereas a lot of my coworkers have that mentality… to show that you’re doing a good job, you have to be in the office at 5:00. The boss’s got to see you sitting at your desk which to me means nothing. You could sit at your desk and be playing Solitaire.

Another respondent, Mark, also mentioned how he considers the traditional idea that being in the office equates to productivity as a misconception:

You and I have talked about people that come into the office and don’t get anything done… when they are in the office they just kick up their feet and they get distracted and just wait around. When they are working from home, they know that they can’t just get distracted because they will have nothing to show for their time at work.

While the productivity benefits of teleworking seemed readily apparent to most of our interviewees, not all of their organizations had leadership willing to make a change from the way they have operated in the past. Half of our respondents (3/6) don’t believe they will be allowed to continue teleworking, and two of those, Kate and Christine, expressed disappointment with their organization’s hurry to move employees back to the office. Christine expressed her confusion as follows:

I’m not sure of the higher-ups’ managing style or exactly why they want people to come back into the office even though I think the employees have proven to be proficient and efficient working at home. From the communication sent to me, it’s because we need warm bodies to provide excellent customer service for students. But other than that I don’t really understand other reasons.

Another theme resonant in the discussion of whether or not organizations will allow teleworking to continue is the idea of trust. While decreased micromanagement and increased independence was identified as a positive of working from home for several of our respondents, the experience of Kate and Christine being asked to return to the office against their wishes suggests that some supervisors are not yet ready to give up all control. There may also be variation in what employers feel comfortable with between individual employees. Jessica shared an anecdote about one of her coworkers whose request to work from home was denied after hers was approved, and she speculated that it was due to a lack of trust between this employee and her supervisor. On the other hand, Cassie expressed that although she feels her employers do trust her, they want her to return to the office simply to better facilitate her job functions, “for my specific role, I think they would want me to go back not because they think I am doing a bad job. They just see how the organization is run and the role I play in that, and I think that would make them want to have me back in the office.”

Discussion

Our research focused on the effects of teleworking on public sector workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though the majority of our interviewees worked in the office prior to the pandemic, most of them had a positive experience working from home despite initial doubts and worries. The results of our study confirm the findings of Morganson et al. (2010) and Kossek et al. (2016) – namely that teleworkers experience a sense of flexibility and independence while working from home, and their job satisfaction increases. However, where Morganson et al. reported inconclusive findings regarding the impact of telework on a work-life balance, our study (although small) indicated that working remotely improved interviewees’ work-life balances. On the other hand, our research confirms Morganson et al.’s claim that teleworking may create a feeling of social isolation, especially disconnect from co-workers and supervisors. Our findings suggest that employees perceive that their productivity increases while working remotely. Kossek et al. (2016) had similar results and found a correlation between telework and higher performance.

The results of our research suggested that teleworking may impact turnover, especially for women who have children. One participant indicated that they would not be able to continue working when they returned to the office, because of the need to take care of a baby and because their low salary was not sufficient to cover childcare. Companies concerned about turnover may consider retaining their female employees by offering telework opportunities. Along these lines, Chung and Van Der Horst’s (2017) study of women’s employment patterns after childbirth suggested that working remotely may help women to continue their employment after childbirth.

The majority of interviewees had an overall positive experience while teleworking and indicated that they would love to continue working remotely full or part time. The one person who felt that teleworking decreased their productivity and morale preferred working from the office; however, this person also indicated that working from home is more difficult for them because their job requires them to be in the office most of the time. Our study suggests that people who can complete their work at home with ease may find more positive outcomes while working remotely. Public sector organizations may consider continuing to allow their employees to telework, at least partially, even after COVID-19 pandemic has ended, as a way to boost employees’ morale, productivity, and retention.

Study Limitations

Our goal with this particular research study was not to generalize our findings broadly—even as we identify common themes among our data—but rather to explore and understand select public sector employees’ perceptions of teleworking in the Salt Lake City area. One must therefore understand our study as a precursor to a larger, more generalizable study. Nonetheless, the qualitative approach allowed us to collect more deep and detailed data regarding employee perceptions and experiences than a quantitative or experimental approach would have permitted.

However, the “extensiveness” of the data might be another limitation of our research design. The data, apart from being time-consuming to collect, was difficult to analyze while also avoiding each researcher’s biases. On the flip side, interviews – despite being time-consuming and difficult to analyze – dealt with human experiences on a deeper level. Therefore, this method was more effective to answer our research question. We tried to combat researchers’ biases by having all researchers read all interview transcripts and identify common themes, as opposed to completely dividing interview transcripts between researchers for analysis.

Conclusion

Through this qualitative study of employee perceptions, we found that interviewed public employees see benefits and drawbacks to telework. Some of the most important perceived benefits included flexibility, increased productivity, and time spent with family. Drawbacks included distractions, difficulties with technology, and lack of connection with coworkers. These drawbacks notwithstanding, the majority of our respondents reported positive views of teleworking and would choose to work from home into the future. The respondents have found important best practices including constant communication and creating a home office that have enabled success in working from home.

It is important for public administrators to note these types of perceptions and experiences to support employee success. Public managers’ related decisions are important for the health of their organizations – as they directly impact the nature and even longevity of many peoples’ employments. Our findings not only help to explain employees’ perceptions of telework, but they can help inform public administrators on whether to continue this trend going forward. These are important public sector considerations, especially as the private sector may begin attracting qualified candidates through a commitment to maintaining a work-life balance through teleworking.

As suggested by this study’s findings, public sector organizations may need to innovate to make working from home a more viable way to meet public demand for their services. If the perceptions of the employees we interviewed are reinforced by further research, teleworking would be one of the most powerful tools managers can use to maximize productivity and boost morale among their employees.

References

Chung, H. & Van Der Horst, M. (2017). Women’s employment patterns after childbirth and perceived access to and use of flextime and teleworking. Human Relations, 71(1).

Dey, M., Frazis, H., Loewenstein, M. A., & Sun, H. (2020). Ability to work from home: Evidence from two surveys and implications for the labor market in the COVID-19 pandemic. BLS Monthly Labor Review. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2020/article/ability-to-work-from-home.htm

Ernst Kossek, E., Lautsch, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2016). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work-family effectiveness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), p. 347 – 367.

Johnson, G. (2014). Research Methods for Public Administrators. New York: Routledge.

Kwon, M., & Jeon, S. H. (2018). Do leadership commitment and performance-oriented culture matter for federal teleworker satisfaction with telework programs? Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(1), 36-55.

Mahler, J. (2012). The telework divide. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 32(4), 407-418.

Morganson, V. J., Major, D. A., Oborn, K. L., Verive, J. M., & Heelan, M. P. (2010). Comparing telework locations and traditional work arrangements: Differences in work-life balance support, job satisfaction, and inclusion. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(6), 578-595.

Riccucci, N.M. (2010). Envisioning public administration as a scholarly field in 2020: Rethinking epistemic traditions. Public Administration Review, 70, S304-S306.

Siha, S. M. & Monroe, R. W. (2006.) Telecommuting’s past and future: a literature review and research agenda. Business Process Management Journal, 12(4), 455-482.

Williamson, K. (2006). Research in constructivist frameworks using ethnographic techniques. Library Trends, 55(1), 83–101.