3

Andre French Lastre; Mishael Garz; Santiago Garcia; and Taylor Greenwell

In the spring of 2020, entire sectors of the U.S. economy closed in weeks – including kindergarten through twelfth grade (K-12) schools – as the COVID-19 pandemic brought many aspects of our society to a screeching halt. To reduce virus transmission, students turned to e-learning (online learning), allowing them to attend school from the safety of their homes – an option that is particularly important for the roughly 40 million U.S. adults that work or live with school-aged children and have risk factors for severe COVID-19 illness (Gaffney et al., 2020). With COVID-19 impacting children, families, and educators worldwide, our study examines the educational modes offered in Utah and why parents prefer one academic format provided during COVID-19 over another. To do so, our empirical study analyzes original data from a surveys of select parents of K-12 students in the Utah education system during the fall of 2020.

The study relies on data from parents who are students in the College of Social & Behavioral Science (CSBS) at the University of Utah. We focused on K-12 education to better understand what education formats are offered in Utah school districts during COVID-19 and why parents may prefer a particular educational format. In particular, we sought to learn what formats survey respondents chose for their K-12 children, the reasons for their selection, and difficulties that have resulted from the various formats.

Literature Review

The purpose of this literature review is threefold. First, we offer a glimpse into some of the benefits students may experience with e-learning, including researchers’ recommendations for educators to improve the likelihood of success in this new learning environment. Second, we dip into literature that illuminates some deficiencies faced by students in online educational systems. Third, we discuss some pros and cons parents consider when choosing their children’s learning formats/modes. Finally, we address a gap in the literature and discuss the unknown impact on the educational future of our children due to quick decision making in the era of COVID-19.

In one study of e-learning, Gilbert (2015) finds some benefits of online education in high school. By surveying students, Gilbert determined many of them thrived because online learning allowed them to work at their own pace, giving them the flexibility and control of their schedules. Furthermore, some students enjoyed online learning more because “they were able to focus completely on the work and not on other factors such as social interactions with peers and physically attending class” (Gilbert, 2015, p. 28). Her research suggests students can be successful with online classes when they do not face adverse extenuating circumstances.

Nonetheless, when a novel coronavirus spread took hold globally in early 2020, schools worldwide were forced to create educational plans suitable for online learning – often in a matter of days. Relatedly, Dhawan’s (2020) synthesis of secondary data offers recommendations on how to overcome challenges to online learning, concluding that a school’s infrastructure, such as a reliable internet connection, needs to be strong enough to provide unhindered services during and after a crisis. Additionally, schools need to plan several scenarios and have back up plans if original plans fail. Finally, Dhawan cautions that if students are to survive changes of transitioning from face-to-face learning to e-learning, they “must possess certain skills such as skills of problem-solving, critical thinking, and most importantly adaptability” (Dhawan, 2020, p. 17).

To ensure educational survivability during crises, Carrilo and Assunção Flores (2020) advise educators utilize “effective practice relating to the use of pedagogical tools and technologies (e.g., gamification, animated clips, videos, wiki tools, podcasts, voice boards, virtual worlds, e-book readers, e-folio…)” (p. 10). They reach this conclusion because new tasks, such as teaching during a pandemic, require different tools. Additionally, they recommend that educators clearly explain participation requirements to students and parents, ask questions confirming the comprehension of ideas, and play a part in leading students towards completing their educational goals. Finally, they observe that for teachers to be successful online educators, they must have a “comprehensive and solid view of the pedagogy of online education” (Carrillo & Assunção Flores, 2020, p. 13). Educators likely need to grasp and utilize all of the tools at their disposal to effectively teach online during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When looking at evidence of online learning effectiveness, Ahn and McEachin (2017) find that among Ohio students exclusively enrolled in e-learning across all subjects and grade levels score significantly lower than those enrolled in traditional in-person charter and public schools. Moreover, they notice lower performance in “high school students across the 10th-grade OGT [Ohio Graduation Test] assessments in math, reading, science, social studies, and writing” (Ahn & McEachin, 2017, p. 48). However, when comparing elementary and middle school students’ achievements in pre and post-e-learning enrollments, it should be noted that students at the higher ends of the achievement levels (i.e. above the 90th percentile) have less pronounced adverse effects (Ahn & McEachin, 2017).

More recently, Wyse et al. (2020) analyze early educational changes made during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through nationwide student assessment data, they show how schools’ abrupt closures and the sudden transition to online education impacted students’ performance levels. The data show that student assessments deteriorated substantially and that early grades suffer the most significant achievement gaps, likely because this is where the most growth in math and reading typically occurs. It is worth noting that the study findings show differences in the adverse impact across subjects, grade levels, and states, and it is yet unknown how long these educational deficiencies will linger.

With the manifestation of some negative impacts after the rushed transfer to e-learning in the spring of 2020, it is no wonder many parents want their children to return to in-person learning for the 2020-2021 school year. For example, through case study research Selwyn et al. (2011) find that many parents are apprehensive about online learning technology; for instance, many parents did not have home internet access or enough available devices for all to use regularly. Furthermore, many parents with home internet and sufficient devices reported high levels of computer illiteracy. Some felt that these technologies were mainly for the school to disseminate information but not for parents to respond. The authors conclude that online learning can not provide a “technical fix to the social issues… [but] appear to reflect and reinforce – rather than reconfigure – existing patterns of school/parent engagement” (2011, p. 323).

Still, not all students or parents form an adversarial relationship with technology or e-learning. Parsons and Adhikari (2016) performed a series of surveys with parents and students who participated in bring-your-own-device (BYOD) schools. Some children reported enjoying more access to information on the internet, increased creativity with presentations and projects, and effortlessly submitting assignments by avoiding printing or traveling to complete the submission. Parents also expressed amazement in the growth in the quality of their children’s presentations, higher motivation in learning through an iPad than face-to-face, and children becoming more independent and organized learners. A parent with a child diagnosed with ADD applauded transitioning to BYOD, as it engaged her daughter in ways traditional teaching did not achieve (Parsons and Adhikari, 2016).

The forced implementation of abrupt changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, disorienting as they may have been, have helped kept teachers and children healthy, while education continues for many. However, many questions remain. To what extent do school districts consider deficiencies in technological and/or high-speed internet access before ordering all students to move online? What are long term impacts on student well-being of denying and permitting face-to-face learning during the pandemic? The truth is no one knows how the move to e-learning will impact K-12 students in the medium and long terms. Our study provides an exploratory basis for such research by shedding light on the educational format choices and perceived impacts of a small convenience sample of K-12 parents in Utah.

Research Design

Our research design approach was empirical data collection relying on the experiences and information of others to shape our knowledge (Ricucci, 2010) – specifically, data collected through an online survey of parents who have children enrolled in K-12 education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to practical limitations of a short time window and restrictions on in-person interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic, we relied on a convenience sample, targeting parents from the University of Utah’s CSBS with children in the Utah K-12 public education system. We discuss the limitations associated with a convenience sample later in the paper.

Data Collection & Analysis

Although our primary method of data collection was an online survey, we began our study with five interviews with acquaintances that have children in the Utah K-12 education system. We used the interviews to both better orient ourselves on the status of public education under COVID-19 and to inform survey development (i.e. identifying and constructing survey questions). We distributed the survey through two channels: (i) the CSBS Dean’s Office included the survey invitation in an email newsletter to all CSBS graduate students, while CSBS staff posted a survey link to the College’s social media pages, and (ii) the a Master of Public Administration Program Coordinator forwarded an emailed survey invitation to all Public Affairs students. The survey was kept open for one and a half weeks.

Forty-five individuals responded to the survey, of which 44 made it to question two. Question two screened those who had children in the Utah K-12 education system from those who did not. Nine respondents (24.45%) had children in K-12 and 35 respondents (79.55%) did not. Those who did not have children in K-12 were moved to the end of the survey and those with students in K-12 were moved to the next question.

Once the survey was closed, we transferred the data into Microsoft Excel, removing the responses of all respondents without children in the Utah K-12 education system. We used a series of descriptive analyses to analyze the quantitative survey data and qualitative content analysis for open-ended responses.

Findings

We begin by reporting the educational formats offered and chosen by the surveyed parents. As reported in Table 1, the most common learning format reported was online only (7 respondents), followed by in-person (4), and then hybrid (combination of online and in person; 3). None of the respondents indicated home schooling as an option. As shown in Table 2, the most frequently chosen educational format was online only (4), followed by in-person (3), and then hybrid (2). One respondent chose “other” as an educational format but did not elaborate on what that option was.

| Educational format | Frequency |

| Online only | 7 |

| Hybrid | 3 |

| In-Person | 4 |

| Home school | 0 |

| Other | 0 |

| Educational format | Frequency |

| Online only | 4 |

| Hybrid | 2 |

| In-Person | 3 |

| Home school | 0 |

| Other | 1 |

To provide a better sense of the students and parents represented in our data, the tables below show a breakdown of respondents by their child’s/children’s schooling characteristics. Table 3 shows the respondents’ distribution across Utah school districts and chosen educational formats. Table 4 shows the the respondents’ distribution across school levels and chosen educational formats. No middle school children were represented in our data.

| Hybrid | In-person | Multiple (hybrid + in-person) | Online | Other | Totals | |

| Alpine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Davis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Granite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Jordan | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ogden | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Salt Lake City | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Totals | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| Hybrid | In-person | Multiple (hybrid + in-person) | Online | Other | Totals | |

| Elementary | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| High school | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Both elementary and high school | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Totals | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

Next, we examined how parents reported how their child/children were doing under the chosen educational formats. As can be seen in Table 5, when presented with the question “”My child(ren) is doing well under the selected educational format(s),” six parents agreed (three “strongly,” one simply “agreed,” and two “somewhat”) and two disagreed. The level of agreement or disagreement varied considerably across parents of children of different chosen educational modes (Table 5) and school levels (Table 6).

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Online only | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hybrid | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| In-person | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple (In-person and Hybrid) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Totals | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Somewhat Agree | Somewhat Disagree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Elementary | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High school | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Both elementary and high school | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Totals | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

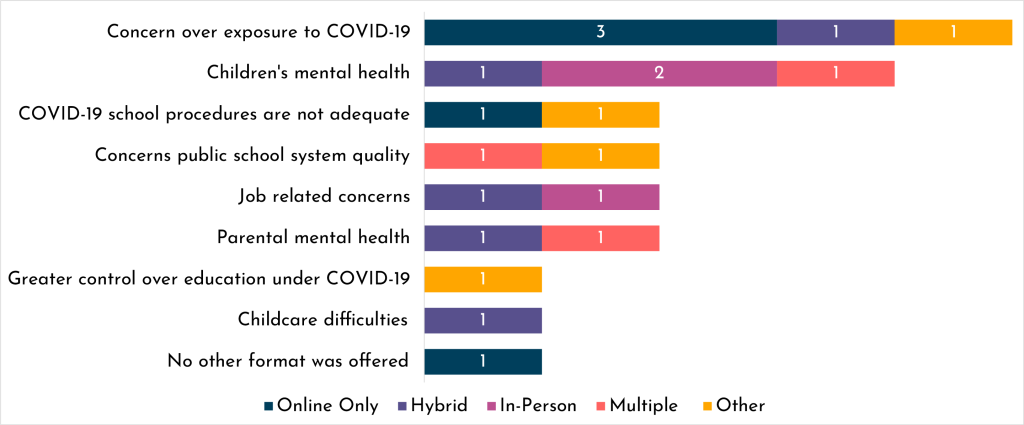

Finally, we examined the factors indicated as having influenced parent’s decisions over what educational format their child/children would pursue (Figure 1). The factors are ranked from most frequently indicated (top) to least (bottom). Not shown are three factors which no respondents selected, including: school COVID-19 procedures are too stringent, internet concerns, and technology concerns. The respondents’ chosen educational formats are indicated by color in the stacked chart. Perhaps not surprisingly, parents who chose online only education tended to express concerns of COVID-19 exposure. Parents who selected the hybrid option (partially online and partially in person) indicated that they had (among other factors) parental mental health concerns and job-related concerns. Parents who chose to send their children in-person seemed to focus on concerns for their child’s/children’s mental health.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to obtain information on different formats of education offered during COVID-19 for K-12 students in Utah and to see if parents preferred a particular educational format. Our data is drawn from a convenience sample of parents that are current students at the University of Utah’s CSBS.

We had set out in this study suspecting that parents who chose online or hybrid education for children did to limit their exposure to COVID-19 and maintain their physical health. We also thought a hybrid option might be pursued out of children’s mental health concerns. We expected that parents would choose an in-person option due to job-related or access-related concerns.

Our study results seems to generally support these expectations. Our findings provide some evidence that, among the surveyed parents, online format selection may correlate with concerns of exposure to COVID-19, while hybrid education seemed associated with parent mental health and job-related concerns. Finally, in-person options were more likely to be selected alongside concerns related to children’s mental health. Of course, survey respondents noted multiple reasons that one format may work best for their child over another. These reasons include too much time in front of a computer, schedule conflicts, frustrations with classroom check-ins for virtual learning options, and students needing to complete more “busy work”. It seems that a one-size-fits-all approach is not practical for every child.

The impact of educational formats and choice is an exceptionally relevant topic as this chapter goes to press, as Utah is experiencing higher than ever COVID-19 cases (Governor Gary R. Herbert, 2020). As COVID-19 is such a rapidly evolving situation, research is still underway, and while we have found other studies consistent with our research, we anticipate new findings will continue to emerge. There is also considerable uncertainty and discussion around the impact of different educational modes during the pandemic. For example, the following pronouncement was recently released: “The consensus of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) and American Psychiatric Association (APA) is that they generally support the CDC’s push to reopen schools for the sake of children’s mental and developmental health” (Safai, 2020). Research also indicates that each situation is unique and that families will have to consider their children’s needs prior to making a decision.

The pandemic has created disruptions to daily life and children are feeling these changes deeply. While the return to school might be exciting for many students, others will be feeling anxious or frightened…Every child is different — one might thrive with virtual learning, and another might not do well. Overall the decision to return to school should be individualized. (Safai, 2020).

In addition to the central survey findings that we note above, the comments of several respondents that we received through a single open-ended question are worth noting. One respondent noted that the online-only format is “far too much screen time for one child.” Research findings on screen time are varied. Many experts indicate that not all screen time is equal and certain online activities are more beneficial than others. The American Academy of Pediatrics dropped its screen time guidelines in 2015 (from two hours or less per day) but suggested that screen time not be used as a substitute for sleep or active time (Hulick, 2020). Other experts note that regardless of the type of screen time, it can negatively impact physical health, primarily vision:

Digital technology has been immensely beneficial in cushioning the disruption to school education, but it is crucial to be cognizant of the impact of increasing dependence on digital devices. While it is important to adopt strict measures (e.g., lockdown and home quarantine) to slow or halt the spread of COVID-19, multi-disciplinary collaboration and close partnerships between ministries, schools, and parents are necessary to minimize the long term collateral impact of COVID-19 related policies on various health outcomes such as myopia, which was already a major public health concern prior to the pandemic. (Wong et al., 2020, p.11)

Future research can and should continue in many ways. First, future research could take a more comprehensive analysis of educational options offered compared with the educational format selected. With a larger sample size than this study, it may be more reasonable to conclude parents’ preferred method of education for their children during COVID-19. Future studies could also include the child’s perspective of options offered and how they feel about their selection.

Second, future research could give more data into the types of educational formats offered and analyze them in greater detail. For our study, we defined the hybrid option as partially online and partially in-person. Further studies could break that distinction down even more to include partially online (live teacher), and in-person or partially online (previously recorded lectures) and in person, etc. Studies could see if the method of modalities changes the perception of the education offered.

Third, further research could assess if the number of active COVID-19 cases in the district area impacts parental and student choice, rather than merely district choice. With the number of cases increasing, will parents or students change their opinion on the learning style and engage with a new method? Fourth, and perhaps the most fascinating, could be to track student and parental choices to see if the education method selected impacts them on a long-term basis. As COVID-19 impacting education is such a current topic, there are many ways that research could continue and provide information on educational formats during a global pandemic. Studies could compare the responses of particular counties, states, or countries and note if one method was preferable.

Limitations

There are several limitations with our study that should be noted. Challenges arose with schools frequently changing the available schooling options for K-12 students. Additionally, with COVID-19 cases surging in Utah, rapidly evolving school timelines could have altered some survey responses. Certain options soon became irrelevant as the state was pushed into an Emergency Order by the Governor, and schools changed their offerings once again (Governor Gary R. Herbert, 2020). One family may have been given the option of online or in-person, but the next day was only given an online version. Depending on the day the survey was taken, results could have varied based on each school district. With a still regularly evolving topic, and on a microstudy level, it is challenging to generalize findings, but we were able to see some common themes. This research study could be a precursor to a more extensive and generalizable study.

Additional challenges included a limited ability to deliver the survey directly to our target audience. The survey had to be sent through university contacts, which did not allow us the discretion of sending surveys on the assumed timeline or allow for reminder emails to complete the survey. The limited communication with the survey email group also prevented us from identifying concentrated areas of parents with children in a Utah K-12 school. Utilizing a university contact also gave the contact some discretion on how the survey was distributed. Our research group intended to circulate the survey via email, but we found that the link was shared via social media as well. As the link was shared via social media, it allowed any viewers and/or followers to have access to the study. We did not notice a large increase in responses, but the survey was potentially accessed by people outside of the CSBS at the University of Utah. Finally, an additional limitation that we noted was the students’ grade levels. Responses were only obtained for students in elementary school and high school. Data for middle school and junior high aged students could give an insight to those in the middle of the spectrum of ages.

Conclusion

Through this study, we sought to better to learn what formats a convenience sample of parents of children in the Utah K-12 educational system chose for their children in the 2020-2021 school year, reasons for their selection, and difficulties that have come from the formats available under COVID-19. We found that parents chose several formats, including in-person, online, and hybrid educational modes. The reasons for selecting different educational modes varied, as concerns related to COVID-19 exposure, parental and child mental health, and quality of education were shared by respondents that chose the same educational format.

In terms of child performance under the various formats, most respondents seem to respond relatively favorably. This finding is noteworthy, because it may indicate that Utah public schools have managed to adapt relatively well to COVID-19. This conclusion does not bar concerns due to performance, however, and as our findings are based on a small convenience sample, one cannot generalize the findings to other parents in or outside of Utah.

Despite the small and convenience sample nature of this research, our study is arguably informative for future research into educational formats and student performance under the COVID-19 pandemic. Initial responses to COVID-19 were reactive by necessity and many difficult choices had to be made leading up to the 2020-2021 school year. As COVID-19 will still be impacting the public school system for the remainder of the school year and potentially further, greater and more comprehensive research into the topic is warranted.

References

Ahn, J., & McEachin, A. (2017). Student enrollment patterns and achievement in Ohio’s online charter schools. Educational Researcher, 46(1), 44-57.

Carrillo, C., & Assunção Flores, M. (2020). COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 466-487.

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5-22.

Gaffney, A., Himmelstein, D., & Woolhandler, S. (2020). Risk for severe covid-19 illness among teachers and adults living with school-aged children. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1-6. DOI: 10.7326/M20-5413

Gilbert, B. (2015). Online learning revealing the benefits and challenges. Education Masters, 303.

Governor Gary R. Herbert. (2020, November 9). Governor Herbert updates state of emergency and public health order. Retrieved from https://governor.utah.gov/2020/11/09/gov-herbert-updates-state-of-emergency-and-public-health-order/

Hulick, K. (2020, September 11). Healthy screen time is one challenge of distance learning. Science News for Students. Retrieved from https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/healthy-screen-time-is-one-challenge-of-distance-learning

Parsons, D., & Adhikari, J. (2016). Bring your own device to secondary school: The perceptions of teachers, students and parents. The Electronic Journal of e-Learning 27, 314-323.

Riccucci, N. M. (2010). Envisioning public administration as a scholarly field in 2020: Rethinking epistemic traditions. Public Administration Review, 70.

Safai, Y. (2020, July 29). Should schools reopen for students’ mental health? Mental health experts say school is important for kids’ developmental health. ABC News. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/schools-reopen-students-mental-health-experts-weigh/story?id=71969959

Selwyn, N., Banaji, S., Hadjithoma-Garstka, C., & Clark, W. (2011). Providing a platform for parents? Exploring the nature of parental engagement with school learning platforms. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 14(1), 314-323.

Wong, C. W., Tsai, A., Jonas, J., Ohno-Matsui, K., Chen, J., Ang, M., & Ting, D. (2020). Digital screen time during COVID-19 pandemic: Risk for a further myopia boom? US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7390728/, 1-15

Wyse, A., Stickney, E., Butz, D., Beckler, A., & Close, C. (2020, Fall). The potential impact of COVID-19 on student learning and how schools can respond. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 39(3), 60-64.