Chapter 8 Conceptualizing Client Lived Experiences: Client Worldviews

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Sophie Yohani, Elaine Berwald, Heather Macdonald, and Allison Reeves

Although this ebook is not intended as a multicultural counselling text, wherein the primary focus is on appreciating the intersectional cultural identities of clients and the impact of culture and social justice on the overall counselling process, we assert that all counselling, including building responsive relationships, is multicultural in nature. In this chapter we highlight key issues related to responsive relationships through the lenses of client ethnicity, Indigeneity, religion, and spirituality as a foundation for thinking critically about the influence of worldview on views of health and healing as well as on the conceptualization of client lived experiences and client preferences.

In terms of the counselling process, there are two main foci in this chapter: (a) continued co-construction of understanding of client lived experiences with a particular focus on exploring clients’ values, beliefs, and worldviews and (b) initial exploration of how clients would like their experiences to be different. Each of these is premised on a shared understanding of how clients picture healthy functioning and how they envision the healing process. Without this understanding it is difficult to create a sense of hope for their preferred present or future. Client worldviews influence how they view time (e.g., linear, circular), how they position heal and healing (e.g., within themselves, as part of community, embedded with land and place). Without attending to these values and beliefs through a process of cultural inquiry, mismatches in assumptions can occur that may lead to relational breakdowns and impede clients’ wellness journeys. As a reminder, when we speak of culture in this ebook, we are using the term broadly to include age, ability, Indigeneity, ethnicity, social class, religion or spirituality, gender and gender identity, and sexual orientation. A number of these are explored in this chapter and the next to provide clear examples of their relationships to health and healing processes and practices.

Figure 1

Chapter 8 Overview

Recommended additional reading

Collins, S. (2018). Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 556-622). Counselling Concepts.

- Chapter 15 (Core Competency 14: Position client presenting concerns and counselling goals within the context of culture and social location.)

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

A. Centring Clients’ Values and Worldviews

Throughout this ebook we have emphasized clients’ values and worldviews. In this section we apply the lens of cultural responsivity more deeply to the central, organizing question introduced in the Introduction: In what ways can the relational practices of the counsellor and the nature of the therapeutic relationship shift, adapt, or be altered altogether in response to the specific cultural identities, contexts, values, worldviews, and needs of each individual client? We examine the importance of culture to relationship-building as well as to conceptualizing client lived experiences, focusing specifically on ethnicity, Indigeneity, religion, and spirituality to exemplify the relational concepts, principles, and practices we want to highlight.

1. Ethnicity

As noted in Chapter 1 Norcross and Wampold’s (2018) research on evidence-based relationships and responsiveness foregrounded client ethnicity as one of the factors for which there is demonstrable evidence of the need to adapt counselling relationships and practices to be responsive to each client. The importance of attending to client ethnicity in counselling was foundational to the evolution of multicultural counselling theory and practice beginning in the 1980s (Sue et al., 1982, 1992, 1998). Soto and colleagues (2018) conducted two meta-analyses of the literature on (a) cultural adaptations based on client ethnicity and (b) therapist multicultural competence. They concluded that client identities, including their intersectionalities, must be considered carefully in designing responsive counselling processes. The necessary adaptations included responsivity to language preferences, cultural alignment of principles and practices, attention to levels of acculturation, and counsellor cultural sensitivity and humility. Interestingly client ratings of therapist cultural competence were strongly correlated with counselling efficacy; however, therapist self-ratings were not. This outcome reinforces the need for a client-centred lens on what works, or does not work, in both relationship-building and counselling practices.

In this next video Gina Ko shares a snapshot of her PhD research journey (Ko, 2019). In her work with minoritized female youth, she was cognizant that she might have had power over them as a doctoral candidate (i.e., highly educated) and as an adult whom they trusted. As she would in her role as a therapist, she was careful to be culturally humble and sensitive to their needs and lived experiences to foster a collaborative process in which the youth’s voices were front and centre.

Lessons learned from minoritized youth

Contributed by Gina Ko

Gina Ko completed her PhD in Educational Leadership in 2019, and the title of her thesis is “The Experiences of Youth from Immigrant and Refugee Backgrounds in a Social Justice Leadership Program: A Participatory Action Research Photovoice Project.” She had the honour of working with six female youth in high school who all identified as Muslim. These young humans were most impressive in that they cared about anti-racism, social justice, mental health awareness, and making their community a better place. In this video Gina shares the youth’s experiences of racism, their socially just stance, and how it was important to them to be anti-racist by speaking up about all forms of racism. She also notes how she was intensely connected to their stories due to the anti-Asian racism transpiring at the time of her study.

© Gina Ko (2021, May 28)

Reflection questions:

- How would you acknowledge clients’ experiences and explore them collaboratively when they tell you that they have, or are, experiencing racism?

- If you are a part of the dominant population, how might this be difficult for you? How would you maintain a stance of openness and responsivity to client needs?

- If you are a part of a racialized population, how would you be mindful not to equate your experiences with those of your clients and instead stay client-centred and open to their unique ways of making meaning of their lives?

2. Indigeneity

Notably neither of the earlier articles on the importance of cultural adaptations in counselling relationships and practices (Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Soto et al., 2018), differentiated between ethnicity and Indigeneity. Collins (2018c), however, argued that counsellors need to think about Indigeneity as distinct from ethnicity in the building of cultural competency, because of the profound impact of colonization on Indigeneity and the unique relationship of Indigenous peoples to the dominant culture. Persons or peoples of other ethnic identities, who have come to Canada as colonizers and settlers, are positioned differently in terms of their lived experiences and social locations. As part of our intention to support decolonization, we have foregrounded perspectives of Indigenous peoples, as the original inhabitants of Turtle Island (Dupuis-Rossi, 2020; Stonefish & Kwantes, 2019), throughout this resource. We are delighted to share with you a second video by Indigenous Advisor, Liaison, and Cultural Carrier, Elaine Berwald in which she speaks to the topic of Indigeneity as it relates to working with Indigenous peoples in counselling practice.

Contributed by Elaine Berwald

As you watch this video, open yourself to deeper understanding of Elaine’s identity and Indigeneity through her reflections on her name and her locating of herself relationally. Consider carefully the implications of her 40-year journey.

© Elaine Berwald (2021, April 26)

Questions for reflection:

- What are the implications of positioning counselling within the broader framework of healing-centred engagement?

- Take a moment to watch the trailer for First Contact, opening yourself to honest reflection on your assumptions and biases about Indigenous peoples in Canada.

© First Contact (2018, August 15)

- How might recognizing that colonization has been a deliberate, systemic campaign over multiple generations that insidiously influences attitudes and beliefs about Indigenous peoples create space for you to be gentle with yourself in unpacking and dismantling your own biases?

- What principles will you carry forward from Elaine’s message about honouring the diversity of Indigenous identity, as you build relationships with Indigenous peoples within and beyond your therapeutic relationships?

Note. The trailer for the original Australian version of First Contact reinforces the global experience of Indigenous peoples within colonial reach.

3. Religion and Spirituality

Although there is now wide recognition of a broader definition of culture, one which includes religion and spirituality as core elements of personal cultural identity (Collins, 2018c), there remains a gap in counselling theory and practice when it comes to the integration of client spirituality into counselling practice (Roysircar et al., 2018). Many clients are influenced in their thinking, affect, behaviour, relationships, and life choices by their connections to religious or spiritual communities, their beliefs and values, or their own personal sense of spirituality (Captari et al., 2018). Therefore culturally responsive, client–counsellor relationships must create space for, and invite attention to, client views of spirituality and experiences of religion (Canadian Psychological Association, 2015).

To provide some insight into what talking about religion and spirituality might actually look like in practice, we invited colleagues to reflect on their approaches to spirituality in counselling. We invited participants who hold diverse spiritual perspectives and religious affiliations to enrich the dialogue, including Mateo Huezo whose perspectives on faith and spirituality in 2SLGBTQIA+ care you will encounter in Chapter 9. First consider Heather Macdonald’s reflections below on the role of spirituality in counselling.

The role of spirituality in counselling: Part I

Contributed by Heather Macdonald (in conversation with Gina Ko)

In this conversation Gina talks with Heather about how she views spirituality as it relates to human nature, lived experiences, and attachment theory.

© Heather Macdonald & Gina Ko (2021, March 29)

Questions for reflection:

- Reflecting back on the influence of connection–disconnection and attachment on relationships (Chapter 5), what resonates for you in Heather’s meaning-making about spirituality and attachment?

- Whatever your belief systems, how might the concepts of security, attachment, and safety be helpful in positioning client spirituality in counselling?

Spirituality can form an important source of identity, resiliency, agency, meaning, coping, and motivation for change for some clients (Captari et al., 2018). Failing to be inclusive of spirituality within the counselling process may leave clients feeling misunderstood or invisibilized by the therapist and may render these strengths inaccessible to support health and healing. Religious and spiritual beliefs are also often intertwined with, and inseparable from, client views of health and healing. Religious affiliation may add another source of strength for clients in the form of social support, a sense of community, principles for living, and so on. What is often unclear to new counsellors is how to start a conversation about spirituality with clients and what it might look like to bring clients’ beliefs, values, and sometimes religious practices, into the therapeutic process.

The role of spirituality in counselling: Part II

Contributed by Heather Macdonald (in conversation with Gina Ko)

In this conversation Heather reflections on how to inquire about spirituality and how to navigate differences in values, beliefs, and worldviews between counsellor and client.

© Heather Macdonald & Gina Ko (2021, March 29)

Reflections:

- What do you think of Heather’s assertion that her faith doesn’t have a place in the therapy room because it is not her room?

- What might it look like for you to privilege each client’s story as they come into the room?

- What might you need to work through to be able to be fully present to all clients, so that you are able to create a safe and more secure space for each one?

- What relational principles might you use to determine whether self-disclosure of your own faith beliefs is relevant to the client’s healing journey?

Spirituality is also an important dimension of counsellor cultural self-awareness, including bringing into consciousness religious or spiritual values that might limit your ability to be open and fully present toward all clients (Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counselling [ASERVIC], 2009). A client-centred, culturally responsive, and socially just approach to inviting attention to spirituality in counselling necessitates centralizing the conversation in clients’ identities, values, beliefs, and worldviews. Towards this end, ASERVIC (2009) developed a set of Spiritual & Religious Competencies to provide guidance for practitioners in addressing these issues, ethically and effectively, within counselling. By assuming a client-centred, culturally responsive positioning, all counsellors regardless of their personal spiritual or religious beliefs and values are better prepared to optimize the therapeutic value of client beliefs and worldviews. Captari et al. (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of 97 outcome studies and concluded that therapy adapted to client religion and spirituality resulted in increases in both psychological and spiritual health. This meta-analysis provided substantive evidence for integrating client spirituality and religion into collaborative conceptualization of client challenges, preferences for change, and therapeutic directions. In the textbox below, we the list of clinical applications provided by Captari and colleagues (2018) using the language and practice principles introduced in this ebook and in Collins (2018b).

Principles for Client-Centred Inquiry and Integration of Religion and Spirituality

- Engage in cultural self-exploration to bring into conscious awareness assumptions and biases you may hold about clients’ religious or spiritual affiliations and beliefs.

- Appreciate the complexity and intersectionality of client cultural identities, attending to the unique perspective and needs of each client.

- Express cultural curiosity, and assume a not-knowing stance about the influence of religion and spirituality (or the lack therefore) on client values, beliefs, and worldviews.

- Foreground client values, beliefs, and worldviews even if these do not align with your religious and spiritual perspectives.

- Explore the cultural meanings clients associate with religion and spirituality and how these influence their day‐to‐day lives.

- Apply the lens of cultural responsivity to both client—counsellor relationships and techniques for conceptualizing client lived experiences.

- Make adaptations to counselling processes and practices to align with client worldviews.

- Engage in cultural inquiry to salience of religion and spirituality to each client’s challenges and preferences.

- Attend to client beliefs, values, and worldviews in setting therapeutic directions, including the possibility of prioritizing spiritual health and connection (or reconnection) to sacred practices or communities.

- Draw on the process of cultural humility to keep ensure conversations about religion and spirituality remain client-centred, not counsellor-centred.

B. Appreciating Views of Health and Healing

Collins (2018) positioned appreciation for the diversity of views of health and healing as foundational to culturally responsive and socially just counselling practice, and in particular, to collaborative conceptualization of client lived experiences. We have revisited the importance of client-centred practice throughout this ebook, most recently in the first section of this chapter. We now highlight the importance of attending to systems of knowledge, both our own as counsellors and those of our clients, as a foundation for relationship-building and shared meaning-making. By recognizing and resisting the tendency to lean into our own views of health and healing, as people and as practitioners, we open the door to embracing an antipathologizing stance that foregrounds and values client ways of knowing.

1. Systems of Knowledge/Meaning

Client views of health and healing can be primarily idiosyncratic, based on their own personal experiences and beliefs. More often their perspectives are embedded in broader systems of knowledge or meaning, often referred to as epistemological perspectives (Collins, 2018). Whether counsellors acknowledge it or not, they are continuously influenced by the epistemologies they have internalized through their own cultural heritage, their interactions with cultural communities and society as a whole, their engagement in sociocultural institutions, and their education and orientation to the professional practice of counselling and psychology. In your relationships with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds, it is important for you to be able to step outside of your epistemological constraints to appreciate what is healthy or helpful to each client you encounter. In the video below we welcome Allison Reeves’s positioning of culturally safe practice as a foundation for ethical practice and for building responsive and client-centred relationships that respect client intersectionalities, acknowledge differential power and privilege, and challenge the imposition of eurocentric views of health and healing.

Contributed by Allison Reeves

In the video below Allison ties together a number of themes introduced in this chapter, grounding them in culturally safe practice. Pay particular attention to the importance of exploring your cultural standpoint as well as respecting the client’s epistemology.

© Allison Reeves (2021, February 10)

Questions for reflection:

- In what ways might eurocentric psychology influence your views of health and healing, whether or not you identify as eurowestern in terms of cultural heritage?

- Consider the ongoing enactments of colonization in Canada and around the world. In what ways are these an expression of eurocentric ways of knowing and being?

- Allison points to the ways in which psychology in Canada has fallen short of the ethics and aspirations of reconciliation. What other examples can you identify from your own personal and professional experiences?

- Consider carefully the distinction that Allison makes between epistemological hybridism (i.e., the ability to think or see reality, including health and healing, in more than one way) and epistemological racism (i.e., western elitism in which other ways of knowing and views of health and healing are stigmatized or marginalized). How can you make space for multiple ways of knowing in your work with all clients?

2. Antipathologizing Approach

Counsellors can intentionally or unintentionally pathologize clients in a number of ways, including the following (Audet & Paré, 2018; Bemak & Chung, 2017; Collins, 2018a; Dupuis-Rossi, 2020; Fellner et al., 2016):

- by positioning client challenges as purely intrapsychic (i.e., ignoring sociocultural and systemic determinants of health);

- by imposing counsellor views of health and healing (i.e., embracing labels or theoretical explanations that don’t fit for the client); and

- by being hyperconscious or unconscious of the influence of cultural and social location on health and healing (i.e., assuming the problem lies with client cultural identities or failing to recognize the influence of culture and social location)

Adopting an antipathologizing approach to counselling begins from the moment counsellors encounter clients. In Chapter 2 we talked about the importance of cultural curiosity and assuming a stance of not-knowing as a way of setting aside our human inclination to make judgments about people and to assume we understand them without investing adequately in understanding their worldviews. In Chapter 3 we emphasized the importance of counsellor cultural humility as a foundation for creating safer and more culturally responsive spaces for clients. The discussion of antiracism and decolonization in Chapter 4 provided a foundation for affirmative practice in which clients’ strengths and resiliencies are fully appreciated. We then introduced microskills and techniques in Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 that focused on developing an in-depth, shared understanding of client lived experiences and the challenges they face. In Chapter 7 we cautioned against premature foreclosure—assuming that you get it—in favour of thickening your understanding of client perspectives. Each of these elements build upon each other to support counsellors to engage in antipathologizing relationships with clients. One of our goals in this ebook is to support counsellors to see clients in their wholeness. This supports envisioning client preferences for how they would like their lived experiences to be different in this chapter. At the core of an antipathologizing approach to counselling is our ability, as counsellors, to embrace cultural responsivity and socially just practice with all clients.

Cultural Responsivity

We have talked about cultural responsivity throughout this ebook. One of the ways to support applying an antipathologizing lens in your work is to intentionally attend to the client’s cultural lens. Rather than engaging in ethnocentric behaviours derived from your worldview as the counsellor, you optimize the counselling experience for clients. In the videos below Sandra demonstrates the difference between culturally responsive and ethnocentric counselling in her conversation with Yevgen.

Culturally responsivity in practice

Ethnocentric (counsellor’s cultural lens)

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, May 28)

Culturally responsive (client’s cultural lens)

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, May 28)

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

A. Engaging in Cultural Inquiry

Inquiry into client culture forms an important foundation for both relational and counselling practices. Cultural inquiry refers to the process of inviting clients to share salient aspects of their client cultural identities and social locations (Collins, 2018). As Heather noted in her videos on spirituality in counselling, some aspects of culture, including spirituality, may not be introduced into the conversation by clients without the counsellor explicitly creating an invitational and secure space. In this sense, cultural inquiry goes beyond certain processes or steps in which counsellors engage. Instead, cultural inquiry is an orientation to practice that applies to counselling with all clients, not a process to be introduced only when cultural differences are visible. As Collins (2018) pointed out “culture is a ubiquitous phenomenon that is shared by all human beings, so curiosity and conversation about culture should be part of our everyday practice as counsellors” (p. 917). Cultural inquiry is also directly tied to counselling outcomes: “Practitioners will experience increased treatment success by regularly assessing and responsively attuning psychotherapy to clients’ cultural identities (broadly defined)” (Norcross & Wampold, 2018, Practice Recommendations, para. 4). Let’s take a few minutes to consider what cultural inquiry might look like in practice.

Contributed by Sophie Yohani

Sophie defines cultural inquiry as the process through which a counsellor engages the client in an exploration of their personal cultural narratives, which are rooted in their values, beliefs, worldview, and views of health and healing.

© Sophie Yohani & Gina Ko (2021, March 29)

Questions for reflection:

- What new principles or practices might you carry forward from this video to engage in collaborative counselling practices with clients?

- How might you increase your comfort with cultural inquiry?

- How might you build a foundation of respect to support your cultural inquiry?

- Consider, in particular, Sophie’s assertion of the importance of counsellors holding a “deep desire” to want to know clients as cultural beings, which shifts understanding of culture inquiry from a skill to a stance.

1. Exploring Cultural Identities, Values, and Worldviews

The process of cultural inquiry targets client cultural identities, values, and worldviews as a foundation for a fuller understanding of their lived experiences. However, it is important to find ways to integrate inquiry seamlessly and naturally into counselling conversations. Increasing your personal comfort level in talking about culture forms an important starting place to engaging clients openly in reflection on their own culture as opportunities to do so present themselves.

Contributed by Sophie Yohani

In this second video, Sophie talks about how she teaches the process of cultural inquiry by inviting her graduate students into an experiential learning process.

© Sophie Yohani & Gina Ko (2021, March 29)

Reflections:

- Consider how you might apply the idea of creating a cultural collage, literally or figurative, with your clients.

- What might change in your approach to cultural inquiry if you picture each client as a unique cultural collage and approach them with the sense of curiosity and deep desire to know them that Sophie spoke of in her first video?

2. Assessing the Salience of Culture

Approaching inquiry about client culture from a stance of curiosity and not-knowing allows clients to offer up those aspects of cultural values, beliefs, experiences, norms, relationships, and so on that are relevant to them in-the-moment and in relation to the particular challenge they are facing. It is very important not to assume that culture is salient and central to the current challenge; however, it is equally important not to ignore the possibility that these dimensions of client identity may influence how they experience or make meaning of their current challenge or how they envision health and healing.

Being colour brave

Listen to this Ted Talk by Mellody Hobson titled, Color Blind or Color Brave.

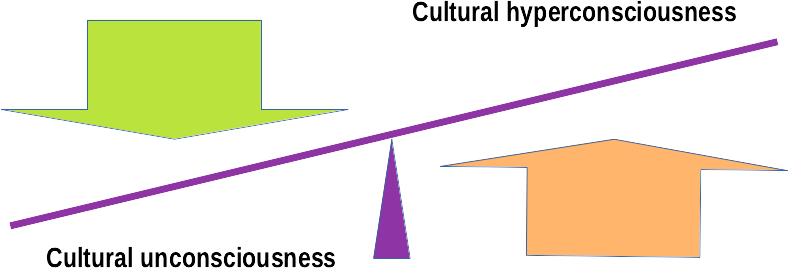

Inadvertent cultural oppression in counselling can result from either cultural unconsciousness or cultural hyperconsciousness. Either an overemphasis or an underemphasis on culture by the counsellor can risk damaging the client–counsellor relationships, lead to misunderstanding their challenges and the contexts in which they arise, or missing out on important pieces of information that could support their health and healing. It can be challenging to figure out how to avoid tipping the balance toward either end of this cultural continuum.

Questions for reflection:

- What is your reaction to Mellody Hobson’s assertion that there is a dominant discourse against talking about race?

- What is your experience of talking about gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, Indigeneity, social class, age, ability, or religion in your personal and professional life?

- Which of these cultural identity factors are you most inclined to avoid discussing and which are you most inclined to introduce into conversation with others? What are the barriers and challenges for you in becoming colour brave (or culturally brave)?

- What would saying, “Yes,” to discussing diversity look like in your counsellor education program, in your workplace, or in other contexts of your life.

Note. From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc11/#colourbrave. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

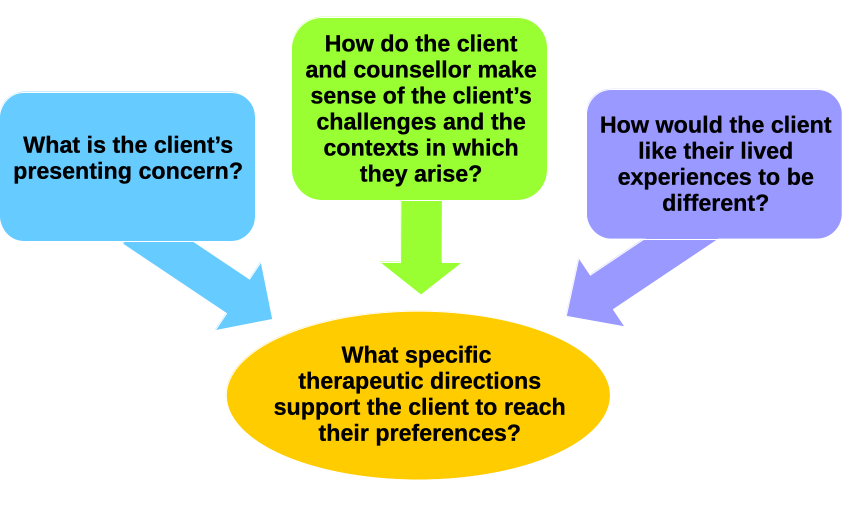

B. Conceptualizing Client Lived Experience

In Chapter 3 we introduced the following structure as a basic guide to conceptualizing client lived experiences and beginning to exploring clients’ presenting concerns. In the chapters that followed, you engaged a variety of microskills to come to a shared understanding of clients’ challenges. We have been building toward an increasingly holistic picture of client lived experiences through this ebook. In this chapter we continue to explore the client’s challenges, and we also move into addressing the third question: How would the client like their lived experiences to be different? With this question comes an invitation to the client to begin to imagine how they would like things to be different.

Figure 2

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

1. Co-Constructing Cultural Hypotheses

In Chapter 7 we invited you to begin to make transparent your evolving hypotheses about the client’s challenges in your counselling conversations. The focus on foregrounding client cultural identities, values, and worldviews in this chapter opens the door to hypotheses that reflect your emergent understanding of the salience of client culture to the challenges they face and the contexts in which these arise. Collins (2018) defined cultural hypotheses as “the working understandings of the implications for counselling of client cultural identities and social locations; they evolve through gaining cultural awareness and engaging in cultural inquiry with each client. These cultural hypotheses should reflect tentative and loosely held assumptions, theories, and connections” (p. 914). In this next video Sandra summarizes some of the factors that influence the process of collaborative conceptualization of client challenges and the development of cultural hypotheses from both the client and counsellor perspectives.

CRSJ counselling: Conceptualizing client lived experiences

As you watch this video, pay attention to the concepts, principles, and practices introduced earlier in the chapter as well as in other chapters of the ebook. Treat this as a review of some of the key elements of the conceptual model we have been elaborating throughout this ebook as well as a preview of others we address in the next few chapters.

© Sandra Collins (2020, December 22)

Reflections:

- As you step back to consider the concepts, principles, and practices in this video, identify those that resonate most strongly with your own evolving views of health and healing. Where are your growing edges or areas of tension?

- Reflect on what you bring to your conversations with clients in terms of both personal and professional experiences and beliefs about health and healing? How might these influence the cultural hypotheses that you develop? What information about the client might you tend to foreground? What might be missed or invisibilized by centring your attention in that way?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. http://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/part/dv/#conceptualizing. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

2. Envisioning Client Preferences

As you begin to work with the client to refine your hypotheses about the nature of the challenge they face, the conversation often begins to include information that moves you into the third question in the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences (Figure 2): How would the client like their lived experiences to be different? Although we spread out the concepts, principles, practices, and skills over eleven of chapters in this ebook, please remember that we are not suggesting a particular timeline, or a linear, step-by-step process, for any of these important elements of building relationships or conceptualizing client lived experiences. Clients may begin to talk about their preferences in your very first conversations, and it is important to recognize and acknowledge their hopes and anticipations. Paré (2013) argued that all client descriptions of the challenges they face contain glimpses (implicit or explicit) of what they would prefer their lived experiences to be like. So far we have focused on developing a rich, thick description of a particular challenge to encourage you not to foreclose too soon on fully understanding client lived experiences. However, clearly defining the challenges clients bring to counselling is only half of the picture; it is equally important that their preferences also be richly defined.

|

|

We are using the language of preferences here to avoid imposing an individualist, eurowestern worldview on clients. Many resources use terms like preferred outcomes or preferred futures. However, there are clients who may not connect to a future-focused visioning process or for whom the language of outcomes may be culturally inappropriate. Part of your role as therapist is to discover or to co-construct language for each element of the counselling process as you journey alongside each client. Client preferences may be expressed in terms of one or more domains of lived experience (i.e., bio–social-psycho-cultural-systemic). Preferences are not the same as change processes. Change processes are the specific activities you engage in with clients to support them to reach their preferences. Our purpose in this ebook is to lay the foundation for change not to introduce specific change processes (often called interventions which is another word we choose not to use in this resource because it is more counsellor-centred). We strongly encourage you not to foreclose on a full exploration of either the paths away from which clients want to move (challenges) or the directions toward which they want to head (preferences). The process of constructive collaboration, introduced in Chapter 6, forms a foundation in this chapter for envisioning client preferences. There are many possible storylines within the counselling process and, more importantly, within clients’ lives. The purpose of envisioning preferences is to support collaborative co-construction of stories that align better with client worldviews, values, hopes, and intentions.

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

The Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary provides a quick reference to each of the techniques introduced in this chapter.

A. Responsive Techniques

The techniques introduced in this chapter and in Chapter 9 are intended to (a) support your continued exploration of the challenges clients face and (b) to develop a picture of their preferences as a foundation for setting therapeutic directions discussed in Chapter 10. The techniques we introduce are reflective of a collaborative and co-constructive relational stance, rather than a particular theoretical model, although you may recognize some of the language and processes as emerging from one or more models of counselling (recall the postmodern and constructivist lens we assume). The appropriateness and relevance of each technique is determined based on client needs, preferences, cultural identities, and contexts, as well as by the focus of the counselling process in-the-moment. These techniques often involve a short sequence of exchanges between counsellor and client focused on a particular purpose.

Variety of Microskills

In the videos in Chapters 2 through 6 we isolated particular microskills to give you clear examples of each. In your practice, however, you will use your skills in a much more fluid and organic fashion, as the therapists demonstrated in the videos in this chapter. However, over-reliance on a narrow set of microskills has the potential to damage the client–counsellor relationship and leave the client feeling frustrated with the conversation. Using a variety of microskills in a flexible and responsive way, enables counsellors to support the relational intentions of the conversation and to effectively introduce broader counselling techniques. The counsellors featured in each video below use a variety of microskills, relatively seamlessly, to support the techniques they demonstrate. Now that you have developed some comfort with the more discrete microskills in the first portion of the ebook, we encourage you to begin to use them more fluidly and purposefully in response to what is happening in the relationship with the client in-the-moment.

1. Exploring Cultural Meanings

In Chapter 6 you were introduced to various microskills, as well as the technique of co-constructing language, that both aim to support shared meaning-making between counsellor and client. The technique of exploring cultural meanings narrows the focus of your co-construction of meaning to client cultural identities, worldviews, values, beliefs, and norms to get a sense of the salience of culture to their current challenge. In Sophie Yohani’s video earlier in the chapter she introduced the process of cultural inquiry, highlighting the importance of these conversations with all clients and noting ways to query client culture that flow naturally from the dialogue between counsellor and client. Cultural inquiry is more effective when approached with an attitude of cultural humility and a stance of cultural curiosity, which together demonstrate a genuine and care-filled interest in understanding the client’s perspectives.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Exploring cultural meanings

Featuring Sandra Collins and Yevgen Yasynskyy

In this video Sandra invites Yevgen to help her understand the significance of cultural and religious rituals and the ways in which their meaning has changed for him over time. Attend to the diversity of microskills she uses to support this conversation.

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yaskynskyy (2021, May 28)

Reflections:

- How might you have responded at various points in the conversation to enhance your shared understanding of cultural meanings for Yevgen? What might you have done differently from Sandra?

- Make a list of additional questions or probes that you could use to continue to explore the meaning of these cultural rituals with Yevgen?

Exploring cultural meanings

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this video Sandra reflects on her lived experiences as a queer person. Gina supports her to explore the meaning she makes of her experiences in the context of shifts in the dominating culture towards more overt expression of hate. Notice how Gina uses a variety of counselling microskills to support this technique of exploring cultural meanings.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 25)

Gina skilfully pulls together language that Sandra introduces by suggesting the concept of rest as resistance as a potentially meaningful metaphor. They will carry this metaphor forward in other conversations.

Preparing for cultural inquiry

You will become proficient and comfortable with the use of all of the skills and relational practices in this ebook though practice. As you anticipate engaging in cultural inquiry with your peer partner in the applied practice activities later in the chapter, or with clients you encounter in the future, pay attention to the barriers you perceive in asking about culture. You may want to spend some time generating a variety of questions or probes to draw in conversations about cultural identities and social locations. Use the table below to support your advance preparation.

| Client Cultural Identities | Questions or Probes |

| Age |

|

| Ability |

|

| Social class |

|

| Ethnicity |

|

| Indigeneity |

|

| Gender |

|

| Gender identity |

|

| Sexual orientation |

|

| Religion or spirituality |

|

Attend to those areas where you struggled to come up with questions or probes that you feel comfortable introducing in your conversations with clients. Take a few moments to lean into that discomfort. What do you discover about your own assumptions or biases in these areas? How might you mitigate those barriers and increase your comfort and proficiency, so that talking with clients about culture becomes as natural as discussing other topics?

2. Highlighting Exceptions

The technique of highlighting exceptions has roots in both narrative and solution-focused therapies. As we noted earlier, every client story once fully explored, will hold glimpses of preferred lived experiences. In some cases, these alternate stories take the form of exceptions to the emergent themes that characterize counsellor and client meaning-making about the challenge the client is facing. The assumption that exceptions exist is grounding in a foundational belief in clients’ strengths, efficacy, resourcefulness, and resiliency. In this sense, highlighting exceptions builds on the response-based approach, introduced in Chapter 4, by drawing attention to the ways in which clients have actively responded to this or other similar challenges. We have waited until Chapter 8 to introduce the technique of highlighting exceptions, because it is important not to overshadow or minimize client thoughts and feelings about their challenges by focusing early or only on the pieces of their story that contrast with, or offer an alternative perspective on, what is currently causing them distress or disruption in their lives. Instead these threads of alternative stories should be gently, respectful, and incrementally foregrounded as a foundation for exploring client preferences.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Highlighting exceptions

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

Gina continues her conversation with Sandra in this video by inviting Sandra to identify times in her life when she is able to rest. Notice how Gina intentionally creates the space for Sandra to slow down, to lean into various dimensions of her lived experience, and to describe in detail what that exceptional time was like for her.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 25)

What specific microskills does Gina use to foreground Sandra’s strengths and competencies. How does Gina use this portion of their conversation to inspire hope in Sandra that she can create her preferred way of being in her life.

Highlighting exceptions

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this second demonstration of the technique of highlighting exceptions Sandra invites Gina to reflect on times or contexts in her life in which she did feel good enough, a metaphor that they co-constructed in previous sessions. We continue to label the microskills to support your increasing comfort with using these skills in a more fluid and responsive way.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 25)

Sandra also thickens the description of Gina’s experience of these exceptions as a way to reinforce this alternative thread in Gina’s story. By introducing the role of therapist, Sandra invites Gina to explore and strengthen the idea that she is good enough.

- What new ideas do Gina and Sandra add to their shared understanding of what it means for Gina to be good enough?

- What other dimensions of Gina’s live experience might you explore to reinforce the good enough exception to Gina’s challenge of perfectionism and lack of balance in her life, which they explored in earlier videos?

3. Envisioning Client Preferences

In every encounter with clients, there are threads for both the contextualized challenges with which they struggle and their preferences. Exploring client challenges provides only part of the picture required to conceptualize client lived experiences (see Figure 2 above). Understanding how clients envision a different experience for themselves is equally important. Exploring challenges and preferences does not happen in a linear fashion, although we describe them sequentially in this ebook. Challenges morph, client perspectives evolve, and new visions for preferred lived experiences may emerge over time.

Orientation to time: A cross-cultural exploration

It is important to recognize that linear views of time (i.e. past–present–future) are embedded in eurowestern worldviews that assume a forward-focused change process. This perspective may prove limiting for clients from Indigenous communities or those from other cultural groups for whom the concept of time can have very different meanings. In some cases, time is viewed as fluid and circular. In others, one’s relationship to time may be defined by the relative importance of events rather than their chronological order. Time may be pictured as shifting between the past, present, and future. An understanding of time may be connected to place, land, ancestors, descendants. The experience of time may be influenced by spiritual practices.

Take a few minutes to search the internet for different beliefs and assumptions about the concept of time. How is time conceptualized? What language exists for time? What is the orientation to time (i.e., past, present, future)? What descriptors are used to illustrate the concept of time? How does the concept of time relate to other dimension of lived experience?

The experience of, and assumptions about, time may have considerable influence on clients’ views of health and healing. Consider what might be required of you, as the counsellor, to be responsive to a client whose view of time differs significantly from your own, particularly as you work with them to envision how they might like their lived experience to be different.

Exploring cultural meanings of time may be an important first step in creating a shared conceptual framework for beginning to talk with clients about how they would like their lived experiences to be different. Some clients may have less attachment to future than to present. In such cases it can be important to come up with shared metaphors for what it could look like for them to no longer experience the challenge in-the-moment, rather than in an imagined future time or space. For some clients the relevant past may include only the experiences, interactions, or contexts that immediately preceded the onset of the challenge they are encountering. In other cases clients may be influenced by a long history of family, community, or societal events that carry forward into the present. Consider this quote from Dupuis-Rossi (2020): “In my practice, I have learned from clients that the pain and distress related to the abuse they suffered in childhood, which is a direct consequence of colonialism, is so overwhelming that it is re-experienced on a daily basis and comes to control and limit their very participation in life itself. It is the eternally present past” (p. 3).

There are a number of common techniques that support counsellors to work with clients to envision their preferences (i.e., to develop equally thick descriptions of where they want to be, who they want to be, what they want their lived experiences to look like). In many cases, this involves engaging the client’s imagination to flesh out what those preferences might look like. We present the techniques in this section with caution, noting the importance for counsellors to assess the cultural relevance of each technique to each client they work with and, where appropriate, the need to co-construct alternative metaphors or ways of making meaning of the absence of the challenge. We will revisit this idea of culturally responsive metaphors for change in Chapter 10.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Notice that each of the questions or prompts in this table draws on a metaphor of some kind. The possibilities for metaphors that are meaningful to diverse clients are endless. We invite you to engage your creativity and to draw on the process of cultural inquiry to generate alternatives that will work for your clients.

Envisioning client preferences: Deconstructing the miracle question

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this example, Gina tests out the future-centred inquiry common in solution-focused therapy by using what is commonly referred to as the miracle question. Notice how Gina welcomes feedback from Sandra about the lack of fit of this approach for Sandra. Attend to the ways in which Gina supports Sandra to provide a thick and multidimensional understanding of her preferences, drawing on Sandra language.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 25)

Notice that we labelled some of Gina’s statements (and earlier videos by Sandra) as questioning or probing even though the wording may not have been crystal clear because the intention for the client was clear. For example, in this video Gina states “I want to ask . . .” but then makes a statement rather than asking a question. Sandra rightfully interpreted this as a question and carried on. Sandra, on the other hand, tends to say “I’m wondering . . . ” as part of her use of probing (see the next video), and again we focus on the intent of the counsellor verbalization as long as the meaning is clear to the client. You will also notice that Gina uses summarizing a couple of times to pull together themes from various sections of this video. You may have thought she was reflecting meaning. The difference is that reflecting meaning references the client’s previous verbalization; summarizing pulls together themes across a number client–counsellor exchanges.

Envisioning client preferences: Inviting cultural languaging

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this video Sandra invites Gina to revisit the language of good enough as an expression of Gina’s preferences for how she would like her lived experiences to be different. Notice how Sandra uses the counselling microskill of providing transparency to bookend this conversation (beginning and ending) as a way of positioning the focus of the conversation, and making it meaningful to Gina, within the broader counselling process in which they are engaged.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 25)

Take a moment to reflect on your own cultural identities and contexts. Consider how you might position the concept of good enough within those lenses. Sandra used the microskill of self-disclosing to be honest with Gina about how Sandra’s worldview limited her understanding of the meaning Gina attached to being good enough. What are the benefits of these transparent worldview conversations for Gina?

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

1. Healing Relational Disruptions

At the time we wrote this chapter, people in Canada and around the world were reeling from the discovery by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation of the remains of 215 children at the former residential school site in Kamloops, B.C. The horror of unspeakable acts triggered renewed calls for action, as well as grief and retraumatization among those for whom these truths were already known.

We invite you to take a moment to reflect honestly on your reactions to this event and the ongoing discoveries of human remains in other places and to the realities of colonization in Canada and around the world. What is triggered for you, as an Indigenous or as a non-Indigenous person? What do you discover as you open to your own mind–body–spirit–heart? All people and peoples are affected by the legacy and ongoing campaign of colonization. It is important, in particular, for non-Indigenous counsellors to engage in honest reflection on how they have been influenced in their thoughts and beliefs, emotions, and relationships by colonial institutions and worldviews. Colonialism affects everyone, and it has broken our relationships to one another.

Consider the metaphor of colonization as “layers of wallpaper in our minds” introduced by Elaine Berwald earlier in the chapter. These layers contain not only beliefs and assumptions about Indigenous peoples, but also beliefs and assumptions about non-Indigenous peoples. Both are internalized and often left unexamined. Elaine invites each of us to gently pull off these layers of wallpaper as we discover assumptions about ourselves, about others, and about our relationships as peoples. Choose one layer to gently remove today, paying careful attention to what you discover underneath it? Reflect on how what you learn about yourself may positively influence relationship-building with all peoples.

2. Enlisting Your Own Story

Alison Reeves introduced the concept of personal cultural standpoint in her video on culturally safe practice earlier in the chapter. The Merriam-Webster (n.d.) dictionary defines standpoint as “a position from which objects or principles are viewed and according to which they are compared and judged.” Choosing a standpoint involves locating yourself within the multiple contexts and systems of influence on your life, including your epistemological lenses or ways of knowing.

As you reflect on your own story, examine critically your epistemological standpoint or ways of knowing.

- In what ways do you, consciously or unconsciously, apply a particular way of thinking or seeing reality to your own story.

- What might it be like for you to embrace epistemological hybridism and to reflect on your story from another perspective altogether (e.g., apply a different cultural lens, explore more fully your cultural heritage, play with different views of time, embrace an antipathologizing perspective)?

- In what ways might you be trapped in your story by your own epistemological racism (i.e., western elitism in which other ways of knowing and views of health and healing are stigmatized or marginalized) or that of others?

3. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Macey’s story Part 8

As you watch Part 8 of Macey’s story, reflect on connections to the various concepts, principles, and practices outlined in this chapter.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yaskynskyy (2021, April 16)

Questions for reflection:

- In what ways might your epistemological standpoint align or misalign with Macey’s experience and her need to be embraced through affirmative and antipathologizing lenses?

- How might you work with Macy to develop a deeper understanding of her views of health and healing?

- In what ways might Macey remain influenced by internalized pathologizing epistemological standpoints, even as she moves forward to embrace the intersectionalities of her identities?

- How might you work together to build a sense of Macey’s preferred lived experiences, attending to her evolving views of health and healing?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

By now, you should be able to distinguish among, demonstrate an emergent proficiency with, and apply purposefully to your counselling, the various counselling microskills introduced in Chapters 2 through 6. Although we may continue to highlight the microskills used by counsellors in some of the videos, our focus now shifts predominantly to counselling techniques. For each technique you will employ a variety of microskills in a way that is responsive to the client–counsellor interaction in-the-moment. We will begin again to lengthen the time for each skills practice activity to increase your comfort with sustaining the counselling conversation over time. For the activities below (except the warm-up activity), please spend 13 to 14 minutes each in your practice sessions.

If you have the opportunity to work with different peer partners to complete these applied practice activities, now would be a good time to switch partners again. By working with different people, you have a chance to practice applying the concepts, principles, and practices introduced in the ebook in ways that are responsive to the needs of each unique client.

Preparation

Identify a challenge with which you are currently struggling, ensuring that you are able to bring some dimensions of yourself as a cultural being into the conversations with your partner. To prepare to talk about how culture relates to you challenge, please complete the collage activity from Sophie Yohani’s video on cultural inquiry to locate yourself and share aspects of your cultural identities, histories, and so on. Treat this as if it was a homework activity from your last counselling session. You can do the collage activity in whatever format you want, spending as much or as little time on it as you choose, as long as you come prepared to provide your partner with sufficient information as a starting place from which to engage you in a cultural inquiry.

If you switched partners this week, feel free to draw on the story you have been working through over each chapter of the ebook. If you are working with the same partner, please choose a different challenge. Whichever challenge is appropriate to your situation, you will use the same challenge for each of the applied practice activities below so that you can build upon and deepen your process of conceptualizing client lived experiences as you try out each of the techniques introduced in this chapter.

1. Warm-up activity: Thick description

(20 minutes)

The purpose of this activity is to co-construct of a thick description of the client’s current challenge, using a variety of microskills, and attending to the influence of cultural identities, values, and worldviews on their lived experiences.

Preparation

Revisit the description of thick versus thin descriptions (Chapter 7) and use a variety of microskills (this chapter).

Skills practice (6–7 minutes each)

Provide each other with a brief summary of your challenges, so that you have a starting place for these conversations and can move more quickly into in-depth exploration.

- Client: Describe what you learned from the cultural collage activity, making ties to the challenge you are currently facing. You may want to share your collage with the counsellor or simple describe relevant components.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on whatever microskills are most useful to engage the client in a conversation about (a) their cultural identities and (b) the cultural connections to the current challenge.

- You will find some of the questions or statements that Sophie uses with her students to teach them about cultural inquiry helpful as a starting place:

- What is present in the collage?

- What is not present?

- Tell me your story.

- Tell me something that I wouldn’t know from the intake forms you completed.

- What are the aspects of your cultural identity you would like me to know about?

- Be sure to use appropriate microskills to begin to co-construct a shared understanding of the challenge and the cultural contexts in which it occurs.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Reflect on what it is like to move from a more prescriptive use of counselling microskills in previous chapters to a more fluid and responsive use of these skills.

- Provide each other with feedback on how thick of a description you were able to elicit from the client and your intentional use of a variety of microskills.

- Discuss the ways in which the salience of culture to each of your challenges was highlighted in the conversation.

2. Exploring cultural meanings

(40 minutes)

Preparation

Revisit the importance of culturally responsivity in conversations, which focuses on the client’s cultural lens as opposed to the counsellor’s worldview (this chapter). Review the technique of making hypotheses transparent (Chapter 7) and the section on co-constructing cultural hypotheses (this chapter).

Skills practice (13–14 minutes each)

The purpose of this activity is to engage in exploration of cultural meaning in relation to the challenge with which you are each struggling. You may or may not come to a place where you can make transparent cultural hypotheses for client consideration. It will suffice for you to simply focus on collaborative meaning-making moment-by-moment as it is related to the cultural influences on the challenge.

- Client: Continue to describe the challenge you are facing, picking up on something meaningful from the warm-up activity. You do not need to take responsibility for introducing the cultural influences on the challenge.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on a variety of appropriate microskills to engage the client in a conversation about (a) their cultural identities and (b) the cultural connections to the current challenges.

- Attend to opportunities to co-construct language for the challenge by foregrounding cultural metaphors that emerge from the conversation.

- You may want to draw on the questions and probes you created earlier in the chapter to support a cultural inquiry about age, ability, social class, and other dimensions of cultural identities.

- Client: Respond as naturally as possible to the counsellor’s use of each of the microskills they choose.

- Counsellor:

- You may find summarizing periodically a useful way of beginning to make your cultural hypotheses transparent (if appropriate) or simply ensuring constructive collaboration in meaning-making about the client’s challenge.

- Toward the end of the video try to synthesize your shared understanding of the client’s challenge and the contexts in which it has arisen.

Reflective practice and feedback

- What bumps did you encounter in exploring cultural meanings with each other? What are the implications of those barriers for working with clients from a diversity of cultural backgrounds?

- Provide each other with feedback on how culturally responsive your interaction was with the client (i.e., to the client’s cultural lens).

- How did your focus on cultural responsivity support an antipathologizing lens?

- In what ways might your personal or professional epistemological standpoints influence how you view the relationship of culture to your own or each others’ challenges?

3. Highlighting exceptions

(45 minutes)

Preparation

Please think ahead to potential exceptions to the ways in which you are approaching, perceiving, or responding to your challenge so that you can support your partner in practising the technique of highlighting exceptions. These exceptions might emerge from reflecting on similar experiences in different contexts, from different experiences over time, from a different aspect of your cultural identity or a context not yet explored, or from a portion of your response to the challenge that differs from emergent themes.

Skills practice (13–14 minutes each)

At this point, you should have developed a thick description of each other’s challenges, considering cultural influences. The purpose of this practice activity is to listen for, and highlight, exceptions to the themes you identified in the first two activities that offer alternate threads or stories.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on whatever microskills are appropriate to continue the process of co-constructing a shared understanding of the client’s challenge.

- Attend to, invite consideration of, or foreground exceptions to the challenge or the ways in which the client is responding to the challenge. Listen for strengths, responses, competencies, perspective-taking and so on that hint at exceptions.

- Client: Respond as naturally as possible to the counsellor’s use of each of the microskills they choose.

- Counsellor:

- Focus on thickening your shared understanding of the exception(s) the client identifies. Where appropriate continue to explore cultural meanings as they relate to the exception.

Reflective practice and feedback

- In what ways did highlighting exceptions to the challenge shift the focus towards answering the question: How would the client like their lived experiences to be different? (See Figure 2.)

- From the perspective of the client, how did foregrounding exceptions to the challenge reinforce your sense of self-efficacy and personal agency, draw out your strengths, or instill a sense of hope that the challenge can be overcome? What specific counsellor verbalizations supported each of these shifts?

4. Envisioning client preferences

(45 minutes)

Preparation

Prepare in advance to talk about the concept of time and its connection to your views of health and healing.

Skills practice (13–14 minutes each)

The purpose of this activity is to begin the process of envisioning preferences with clients (i.e., How would the client like their lived experiences to be different?). However, this time it is important to be coming from a place of cultural understanding of the meanings that the client attaches to time, change, health, and healing.

- Counsellor:

- Begin by introducing the idea that how individuals think about health and healing is embedded in their cultural beliefs about time and change.

- Then invite the client into an exploration of these concepts as they relate to envisioning how they would like their lived experiences to change or foregrounding cultural metaphors that could be useful in the process of envisioning preferences with the client.

- Counsellor and client:

- You may choose to pause your video at this point for a short debrief and to come to a consensus on how you could adapt the language and foci of the techniques illustrated in the chapter to suit the perspectives of the client.

-

-

-

-

-

- OR

-

-

-

-

-

- You may continue to record this portion of the conversation, recognizing that you may need to extend the length of your skills practice session.

- You may choose to pause your video at this point for a short debrief and to come to a consensus on how you could adapt the language and foci of the techniques illustrated in the chapter to suit the perspectives of the client.

- Counsellor:

- Implement the suggested techniques for envisioning client preferences or the adaptation of language and foci you co-constructed with the client, drawing on a variety of microskills.

- Toward the end of the video try to synthesize your shared understanding of how the client would like their lived experiences to be different.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How did your conversation about cultural beliefs related to time and change influence your choices of techniques for envisioning preferences?

- In what ways might your personal or professional epistemological standpoints influence the approach you lean toward? How might your theoretical orientation influence these choices?

- How will you navigate these personal and professional preferences in a way that supports client-centred, responsive practices?

5. Wrap-up

(30 minutes)

Choose a technique that each of you found most challenging, and complete one more round of skills practice (13–14 minutes each). You do not need to choose the same technique.

REFERENCES

Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counselling. (n.d.). A white paper of the Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counselling. https://aservic.org/aservic-white-paper/aservic-white-paper-2/

Association for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counselling. (n.d.). Competencies for addressing spiritual and religious issues in counselling. https://aservic.org/spiritual-and-religious-competencies/

Audet, C., & Paré, D. (2018). Preface. In C. Audet and D. Paré (Eds.), Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice (pp. xviii–xx). Routledge.

Bemak, F., & Chung, R. C. (2017). Refugee trauma: Culturally responsive counseling interventions. Journal of Counseling and Development, 95(3), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12144

Captari, L. E., Hook, J. N., Hoyt, W., Davis, D. E., McElroy-Heltzel, S. E., & Worthington, E. L. (2018). Integrating clients’ religion and spirituality within psychotherapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1938–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22681

Canadian Psychological Association. (2015). CPA Policy Statement on Conversion/Reparative Therapy for Sexual Orientation. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Position/SOGII%20Policy%20Statement%20-%20LGB%20Conversion%20Therapy%20FINALAPPROVED2015.pdf

Collins, S. (2018a). Collaborative Case Conceptualization: Applying a Contextualized, Systemic Lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 556–622). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018b). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018c). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Dupuis-Rossi, R. (2020). Resisting the “attachment disruption” of colonisation through decolonising therapeutic praxis: Finding our way back to the Homelands Within. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 8(2). https://pacja.org.au/

Fellner, K. (2018). Therapy as ceremony: Decolonizing and Indigenizing our practice. In N. Arthur (Ed.), Counselling in Cultural Contexts: Identities and social justice (pp. 181–201). Springer.

Fellner, K., John, R., & Cottell, S. (2016). Counselling Indigenous peoples in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 123–147). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Ko, G. (2019). The experiences of youth from immigrant and refugee backgrounds in a social justice leadership program: A participatory action research photovoice project [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Calgary.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Standpoint. Merriam-Webster dictionary. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Roysircar, G., Studeny, J., Rodgers, S. E., & Lee-Barber, J. S. (2018). Multicultural disparities in legal and mental health systems: Challenges and potential solutions. Journal of Counseling and Professional Psychology, 7, 34–59. http://www.thepractitionerscholar.com/index

Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Domenech Rodríguez, M., & Bernal, G. (2018). Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: Two meta‐analytic reviews. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1907–1923. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22679

Stonefish, T., & Kwantes, C. T. (2017). Values and acculturation: A Native Canadian exploration. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 61, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.09.005

Sue, D. W., Arredondo, P., & McDavis, R. J. (1992). Multicultural counseling competencies and standards: A call to the profession. Journal of Counseling & Development, 70(4), 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01642.x

Sue, D. W., Bernier, J. E., Durran, A., Feinberg, L., Pedersen, P., Smith, E. J., & Vasquez-Nuttall, E. (1982). Position paper: Cross-cultural counseling competencies. The Counseling Psychologist, 10(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000082102008

Sue, D. W., Carter, R., Casas, J. M., Fouad, N. A., Ivey, A., Jensen, M., LaFramboise, T., Manese, J. E., Ponterotto, J. G., & Vazquez-Nutall, E. (1998). Multicultural counseling competencies: Individual and organizational development. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452232027