Chapter 7 Relating in Client and Culture-Centred Ways

by Gina Ko, Sandra Collins, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Ana Azevedo, Jon Woodend, and Ivana Djuraskovic

One of the central themes of this ebook is the importance of being flexible and adaptive in responding to the needs of each individual client. Counsellor responsivity includes adjusting counselling style, communication patterns, approaches to counselling, and the activities in which counsellors and clients engage, in a client-centred way. It is important to remember that the counselling process should be less about the counsellor’s views and inclinations than about those of the clients with whom they work. Given the diversity of clients you are likely to encounter, embracing the not-knowing stance introduced in Chapter 2 and learning to be flexible and responsive with each client is essentially for client-centred practice.

Understanding client perspectives and inclinations is possible only by intentionally gathering practice-based evidence, in particular, direct feedback from clients. For example, you may value collaboration with clients; however, there are clients who may come with expectations of a more directive approach. We invite you to consider your comfort level with responsive flexibility throughout this chapter. These themes carry forward into the techniques we introduce. Although we do not address change processes, or the theoretical foundations of those processes, in this ebook, we invite you to begin to think about how responsivity to the uniqueness of each client has implications for theoretical flexibility and for co-constructing change processes that are meaningful to each client. This type of interpersonal and theoretical flexibility has gained considerable research support in terms of what contributes to positive counselling outcomes.

Figure 1

Chapter 7 Overview

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

A. Client-Centred Practice

Swift and colleagues (2018) conducted a meta-analysis of the impact of client perspectives on counselling that was published in the special edition on evidence-based responsiveness in psychotherapy of the Journal of Clinical Psychology. They explored the “specific conditions and activities that clients desire” within the therapeutic process, and they concluded that there was “increasing evidence pointing to preference accommodation as facilitating psychotherapy outcomes” (p. 1924). In other words: it is important to listen to client feedback in terms of what works for them.

1. Client-Centred Activity, Approach, Therapist Characteristics

Swift and colleagues (2018) categorized the elements of the counselling process about which clients have particular inclinations as follows:

- Activity includes the format of working together, the use of between session activities (i.e., homework), or the type of counselling modality (e.g., single-session, group work, family therapy).

- Approach includes models of counselling (i.e., theoretical orientation), approaches to change (including specific change processes or interventions), and the foci of change (e.g., biological, psychological, social).

- Therapist characteristics refer to the type of practitioner, including both demographics (i.e., cultural identities) and personal characteristics (e.g., directive vs. nondirective).

They concluded that client dropout rate was 1.79 times higher when client perspectives or needs related to activities, approaches, and therapist characteristics were not taken into consideration by the therapist. Responsivity to client inclinations resulted in a small, but meaningful difference in client outcomes. In both cases, clients were better served by being offered choices in activities and approach (Swift et al., 2018). They also concluded that therapist responsivity to client cultural worldview was most often more significant that client–counsellor matching based on shared cultural identities (although there are clearly times when such matching is the most appropriate option).

Although we are not critiquing specific counselling models, by centring relational practices in this ebook, we do want to reinforce the importance of some degree of theoretical flexibility on the part of counsellors (Ginsberg & Sinacore, 2015; Paré & Sutherland, 2016; Scheel et al., 2018). For those of you who lean towards a singular model of counselling, you may want to consider how you will adapt your approach to be responsive to specific clients with particular goals, who bring with them unique and contextualized lived experiences. In this section, and the next, we introduce some considerations related to assessing counselling activities, approach, and therapist characteristics from a client-centred perspective. Relational responsivity may also be expressed differently across various counselling modalities.

Reflections on counselling modalities

Reflect on your current practice experience, the options available for your counselling practicum, or your long-term professional practice plans.

- How might different counselling modalities (i.e., single session, fixed session, open-ended models) influence how you build relationships with clients?

- How might your perspectives on relationship-building and the relational context of counselling influence your approach to how counselling is delivered?

- What biases towards one modality or another do you currently hold? Imagine yourself in your currently least-preferred option. How might you optimize relationship-building in that context?

As noted by Swift et al. (2018) and others (Collins, 2018a; Ginsberg & Sinacore, 2015; Paré & Sutherland, 2016), cultural responsivity is an important dimension of adaptability to client needs. Swift et al. (2018) reported that therapist attitudes and values may have more influence on responsivity to clients than therapist cultural identities or social locations. Their observation brings us full circle to talking again about the importance of counsellor ways of being and engagement in values-based practice, specifically with a focus on client-centred cultural responsivity.

Cultural intelligence & adaptability

Contributed by Ana Azevedo

In this video Ana Azevedo shares her model of cultural intelligence (CQ) and adaptability that is based on four key capabilities: knowledge, motivation, metacognition, and behaviour. As you watch this video, consider the implications of your level of CQ and adaptability for responding in a client-centred way in counselling.

© Ana Azevedo (2021, May 3)

In the Reflective Practice section (later in the chapter) we will invite deeper consideration of the four CQ capabilities Ana introduced. For now consider the following questions for reflection:

- Where would you position yourself on the scale that Ana introduced:

React . . . . . . Recognize . . . . . . Accommodate . . . . . . Adjust . . . . . . Automatically Adjust? - What might the implications of your position be for your cultural responsivity and adaptability to client perspectives in counselling?

- What are the barriers to moving to a place of automatic adjustment to cultural cues from clients or others? What strengths might you draw on to support an increase in your CQ?

- Which of the CQ capabilities do you find most challenging? What is it about that aspect of CQ that results in your cognitive, emotional, or behavioural discomfort?

We will expand on the process for engaging in conversations with clients about their cultural identities in Chapter 8 when we explore client culture and sociocultural contexts.

2. Institutional Ways of Being

One significant factor not discussed in the article by Swift and colleagues (2018) on client-centred practice, is the challenge that clients, and sometimes counsellors, face as they bump up against institutional ways of being. It is beyond the scope of this ebook to take up conversations about the need for structural or systemic policy change (Collins, 2018b; Roysircar et al., 2018). However, it is important to acknowledge the influence of institutionalized, colonial systems, including many healthcare systems, on Indigenous clients and others from marginalized populations (Collins, 2018b; Roysircar et al., 2018; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). These challenges raise the question of how counsellors might carve out safer spaces for both the expression of, and relational responsiveness to, client disclosures and feedback about worldviews.

Reflections on institutional ways of being

Take a moment to reflect on the institutional contexts of your experiences as a client, as a student, as a practising therapist or other healthcare practitioner.

- What are your observations about the worldviews that are prioritized in educational and healthcare settings?

- In what ways do these settings continue to enact colonial or eurowestern worldviews?

- How might those dominant discourses and ways of being influence the responsivity of services to clients?

- What are the implications of institutional ways of being within counselling and psychology for creating space in which client worldviews and related preferences can be centred?

- To what degree might your perspective on institutional ways of being be affected by your own social location and position of relative power within those institutions?

- How might your relationships with clients and your approach to practice allow you to carve out client-centred, culturally responsive space even within oppressive institutional contexts.

B. Counselling Style

We have tapped into various aspects of counsellor and counselling style in our conversations throughout the first six chapters focused on: counselling conventions and honouring first language (Chapter 1); ethic of care and ways of being (Chapter 2); cultural self-exploration and humility (Chapter 3); collaboration and empowerment (Chapter 4); presence (Chapter 5); and constructive collaboration (Chapter 6). Our emphasis on critical reflection on relational practices stems from our belief that client engagement, safety, and outcomes in counselling are enhanced by actively and intentionally choosing and adapting counsellor and counselling style to each client (Kassan & Sinacore, 2016; Willis-O’Connor et al., 2016). We also want to pre-empt you from defaulting to comfortable and easy patterns of interaction that derive from your own worldview, views of health and healing, personal preferences or dispositions, relationships preferences or experiences, and other factors that do not consider client perspectives and needs (Collins, 2018a).

1. Directive Versus Nondirective Approaches

Throughout this ebook we have invited you to engage collaboratively with clients in all aspects of the counselling process. Our focus on collaboration is grounded in emergent evidence of the significant influence of collaboration on client engagement and outcomes in counselling (Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Parrow et al., 2019). Collaboration is also foregrounded in many counselling models that support cultural responsivity in client–counsellor relationships and counselling processes (Collins, 2018a; Paré, 2013; Ratts et al., 2015). However, it is important to examine critically what we mean by collaboration, particularly in response to the call to adapt our activities and approaches to client views of counselling activities, approaches, and therapist characteristics (Swift et al., 2018).

Is it OK to impose our values related to collaboration on clients?

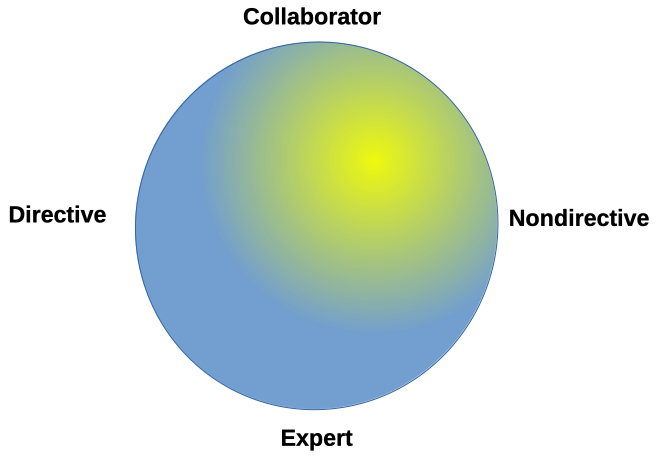

Reflect on your own emergent theory(ies) or model(s) of counselling or your integrative positioning, as well as your personality and preferred ways of interacting with clients. Then position yourself on the image below (i.e., If the client had no influence on your counsellor style, where would you place yourself?). Please be as honest as possible.

Now consider the following situation.

Phoebe comes to the university counselling centre for a single-session career orientation that is part of career week at the university. She comes with very specific questions about how to choose the best option for her career based on the expectations of her parents, who still live in Hong Kong, and the information she has gathered from her first semester in Canada. She has also done her research about you and knows that you have considerable expertise in career decision-making. She assumes this means you will help her decide which educational path to following before she registers in her next semester courses. She is not interested in talking about her values, dreams, or preferences. She has been told by her parents to choose the most lucrative path with a high probability of immediate employment upon graduation.

Reflect critically on how to balance congruence of your own counselling approach and style with the call to responsiveness and adaptation to each client’s preferences and needs, using Phoebe’s story as a starting point.

Then, consider the influence that we (Sandra, Gina, and Yevgen) may have had on your experience with this activity, because we placed the warm yellow glow in the upper right quadrant of the image. To what degree did you want to position yourself as a nondirective collaborator based on the way the image was designed? Although we also may favour this position in our work and writing, this is a caution to all of us to attend to how personal–professional perspectives may inadvertently override client-centred perspectives.

Note. From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#collaboration. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

An invitation to collaboration does not mean that everything you engage in with clients must be collaborative in nature. Instead, it means that you collaborate actively with clients to determine the activities, approach, and other aspects of the counselling process based on client worldview, inclinations, and needs. Some clients may prefer a nondirective approach, whereby they are given the space to talk and generate their own insights and ideas. Clients from some nondominant groups (such as those from an Asian background) may prefer a directive approach, although we caution you not to make assumptions based on cultural identities. Some clients can benefit, under certain conditions, from a more directive approach, in which the balance is tipped towards the expertise of the counsellor or towards providing information, rather than a nondirective approach (Kim & Park, 2015; Willis-O’Connor et al., 2016). In such a case you may rely on microskills such as providing transparency, probing, and clarifying rather than more open questioning. However, it is important to continue to actively negotiate and regularly revisit client views about counselling style, because client needs and perspectives may shift over time (Willis-O’Connor et al., 2016). In particular some clients may become increasingly comfortable with a more self-directed and collaborative process as they enhance their sense of confidence and agency.

For international students in post-secondary education, for example, their experiences could involve challenges with English proficiency and a lack of social connection (Woodend et al., 2016). They may seek out, and need, a more directive approach, including soliciting advice (Woodend et al., 2016). It is important to gauge what clients need in terms nondirective versus directive approaches in order to remain client-centred. Positioning counselling as a relational practice focused on the unique needs of each client invites consideration of adaptation of counselling style in service of each client; in other words, counselling style is about the client not about the counsellor (Paré, 2013).

Considerations for counselling international students

Contributed by Jon Woodend

In the video below Jon shares some key points about adapting counsellor style to be responsive to the needs of international students.

© Jon Woodend (2021, April 20)

Drawing on Jon’s three practice points, consider the following prompts for reflection.

- How might you best prepare to adapt the way that you meet your international student clients’ needs?

- How might you apply this adaptive approach to the informed consent process with international student clients?

- How might you draw on the relational principles of being adaptive and establishing trust to navigate your role and relationships with international student clients?

- In what ways might these three principles support your work with other clients from diverse backgrounds?

2. High-context, low-context communication

There are many ways in which both counsellor and client cultural identities and social locations can influence the ease of understanding within counselling conversations. Ratts et al. (2015) called on counsellors to enhance their communication skills for working effectively with clients from both dominant and marginalized populations. One of these factors is high-context versus low-context communication styles. Take a few minutes to work through the following learning activity to deepen your understanding of the influence of context on communication.

High-context versus low-context communication styles

Watch the following YouTube video about high-context and low-context communication styles.

© Tero Trainers (2016, November 8)

Consider the relationship between communication styles and cultural values below (Zakaria, 2017). Be aware of the risk of stereotyping as you engage in this activity, remembering that (a) personal cultural identities are constructed in ways that often blend and adapt cultural worldviews, and (b) each individual constructs their own ways of being in the world based on multiple factors and intersecting identities.

- High-context communication styles: A lot of unspoken information is implicitly transferred during communication; many things are left unsaid, and meaning is derived through cultural context, social location, and culture-specific interpersonal roles. The speaker’s behaviour, nonverbal cues, and word choice become very important, because a few words can communicate a complex message to other members of the same cultural group. In the context of cross-cultural communication important meaning can be lost. High-context styles tend to exist in cultures that hold collectivist values (e.g., interpersonal relationships, harmony, and consensus).

- Low-context communication styles: Most, if not all, information is exchanged explicitly through the specific words that are used, and rarely is anything implicit or hidden. The communication is more direct, succinct, and linear. Low-context styles tend to correspond to more individualistic cultures where autonomy, individual achievement, and linear logic are valued.

Next, watch the three short scenarios in the video below that demonstrate: (a) within-culture high-context communication, (b) within-culture low-context communication, and (c) cross-cultural high-context versus low-context communication. Ensure that you are able to differentiate among them.

Questions for reflection:

- What did you notice in the outcomes of the conversations, based on the match or mismatch between low-context and high-context communication styles?

- What are the potential implications for client–counsellor communication and the co-construction of meaning?

- Which type of communication style most characterizes your way of interacting with others?

- How might you assess the type of communication style preferred by your clients? If there is a mismatch in your communication styles, what strategies might you use to mitigate miscommunication?

Note. From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#highcontext. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

3. Inclusion of significant others

Swift and colleagues (2018) included attention to client needs related to the setting and format of counselling in their definition of counselling activities. Although they did not specifically address differences in worldview, they did note reticence to attend counselling by members of nondominant ethnic groups, because of fear that their perspectives might not be accommodated. In Chapter 1 we talked about the stigma of counselling and the need to adjust counselling conventions to accommodate client needs. It is important for counsellors who are embedded eurowestern worldviews, personally and professionally, to appreciate the interconnectedness and interdependency of family and community that often characterizes collectivist perspectives (Bemak & Chung, 2017). In more collectivist cultures the experience of health and healing, as well as health-related decision-making, rarely occur outside of relationship with others (Bemak & Chung, 2017; Fellner et al., 2016; Nitza, 2017). Consider the implications of embracing client preferences and needs stemming from collectivist worldviews as you enjoy Ivana’s stories in this next video.

Embracing collectivism by welcoming others into the healing space

Contributed by Ivana Djuraskovic

Ivana shares her experience of growing up in a collectivist culture and contrasts that cultural context with the context she and her parents experienced coming to Canada as refugees. As you listen to Ivana, reflect on your own worldview and cultural contexts, and consider how you might bridge collectivist and individualist worldviews.

© Ivana Djuraskovic (2021, April 25)

Prompts and questions for reflection:

- Picture yourself arriving in the waiting room and being greeted by the extended family or other significant community members accompanying the client. What is your gut reaction as you consider this situation? How might you prepare for this possibility?

- Alternatively, what would it be like for you to work within a more individualist model (for example with clients from eurowestern perspective) if you come from a cultural community in which you are primed to think about health in a more family- and community-focused way.

- What do you think of the argument that even if there is only one person in the session with you, clients bring with them their family, friends, ancestors, and other significant others? What are the implications for how you explore and conceptualize the multiple dimensions of their lived experiences?

- How might you prepare yourself to embrace whatever and whomever enters into the counselling process moment-by-moment?

At the end of their article on accommodating client perspectives and needs in psychotherapy, Swift and colleagues (2018) provided a list of practice guidelines. We have paraphrased several of those key points here, drawing on the relational principles introduced in this ebook, to reinforce their argument that client-centred practices should be prioritized over counsellor preferences:

- Create a climate of cultural safety, mutual respect, and power-sharing to remove barriers and to support clients to talk about the activities, approaches, and counsellor ways of being they prefer, making this an open invitation not an expectation.

- Dispel the mystery of counselling and increase client understanding of the options available to them to ensure they can make informed choices based on their worldviews and needs. This includes offering up your perspective tentatively and respectfully to support constructive collaboration.

- Revisit their perspectives throughout the counselling process, recognizing that these can change as counselling progresses.

- Establish processes for collecting client feedback on an ongoing basis to continuously invite consideration of their perspectives and inclinations.

We pick up on the latter recommendation in the next section when we explore the importance of practice-based evidence to decision-making throughout the counselling process.

C. Client Feedback

You are exposed, via the videos offered throughout this ebook, to examples of practice-based evidence wherein a client provides feedback on what was happening in the counselling process or relationship, directly or indirectly, either spontaneously or in response to a counsellor query. Paré (2013) argued that centring our clients as collaborators within the counselling process positions them to be our best sources of feedback and supervision. You have learned how to invite feedback implicitly by using the microskill of perception checking to ensure you are accurately reflecting client thoughts and feelings as well as by providing immediacy as you note changes in client nonverbal behaviours or reactions in-the-moment. It is also important to build in more explicit invitations to clients to engage in the process of constructive collaboration by evaluating and providing feedback on the counselling process, sometimes in-the-moment and sometimes in a more systematic way (Paré & Sutherland, 2016).

In the applied practice activities throughout this ebook you have the opportunity, as both counsellor and client, to practice inviting, receiving, offering, and collaboratively assessing feedback on your development of proficiency with microskills and techniques, as well as your implementation of responsive relational practices. We hope this will instill in you a readiness to ally with your clients in this way. Each of us, as counsellors, develop our own ways of engaging clients in active collaboration in the counselling process, and inviting their feedback is an important element of this. Client feedback is an essential foundation for engaging in culturally responsive, client-centred practice. Centring the relationship in counselling enhances your ability to keep the focus of the conversation on the client, rather than shifting attention to your own perspectives, needs, agendas, or reactions (even those that are driven by theoretical agendas).

Inviting client feedback: Relational practices and microskills

In the video below Gina and Sandra brainstorm ways in which they invite clients, on an ongoing basis, to provide them with feedback about the counselling conversation and process. Attend to how they pair broader relational practices to the intentional use of specific microskills.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, May 6)

What additional strategies might you draw on to invite client feedback? You may want to try some of these out in your applied practice activities to personalize your approach in a way that feels comfortable and authentic for you.

Client feedback may focus on what is happening in-the-moment in the client–counsellor interaction, on a particular segment of a conversation, or on the counselling process as a whole. In Chapter 10 we will introduce the process of routine outcomes monitoring as a more formal way of soliciting feedback from clients about the efficacy of the counselling process.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

A. Multidimensional Exploration of Client Lived Experiences

In Chapter 5 we focused on the domain of affect and embodiment, encouraging you to invite clients into an in-depth exploration of their feelings in relation the challenge they are facing. Then in Chapter 6 we introduced the domain of thoughts and beliefs, encouraging you to co-construct language with clients as a foundation for meaning-making. However to fully understand and appreciate client perspectives and experiences, it is important to throw as wide a net as possible to co-construct a picture of the client’s challenges and their contexts. Consider, for example, the domain of behaviour or action. In some cases it is important to focus on what the client has done or is doing in response to the challenge, often for the purpose of highlighting the strengths, competencies, agency, and resources they exhibit or engage.

Recall the bio–psycho–social–cultural–systemic model introduced in Chapter 4 as a framework for conceptualizing client lived experiences. The social domain is another important source of information about the client, the challenges they face, and the social supports and resources available to them. In the video on honouring collectivism by Ivana Djuraskovic (above), she emphasized the importance of attending to family, ancestors, community, and other social influences on each client’s way of being in the world and how they make meaning of their experiences.

It is important to be able to tease apart client experience into various domains, particularly so that (a) you do not neglect to attend to certain dimensions, or (b) you resist the inclination to focus on the areas in which you either feel comfortable personally or lean into professionally as part of your orientation to counselling practice. Exploring various domains of experience also helps clients gain a more complete and integrative picture of what is going on for them. One caution, in the context of our focus on client-centred practice in this chapter, is that the boundaries of this exploration must be defined by the client in the context of ongoing informed consent. It is important to follow their lead in terms of what is relevant and salient to their particular presenting concern.

In Chapters 8 and 9 we will explore more fully the cultural–systemic factors; however, we want to step back in this chapter to remind you to consider how the various dimensions of client experience come together in the process of creating a shared understanding of the challenges they face and the contexts in which these challenges arise.

Conceptualizing client lived experiences: Bio–psycho–social–cultural–systemic considerations

Consider the story of Anika (introduced below). As you listen to Anika’s story, write down as many questions as you can to guide your inquiry into their lived experiences. Attend to how your curiosity may support your work together to co-construct a shared understanding of the challenges Anika faces.

© Sandra Collins (2020, December 21)

Note. From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#CRSJconceptualizing. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Next, organize your questions under the following domain factor headings: biological, psychological (divided into thoughts, feelings, and actions), social, cultural, and systemic. Pay attention to the domains in which you generated the most questions. What meaning do you make of any gaps or over-representations?

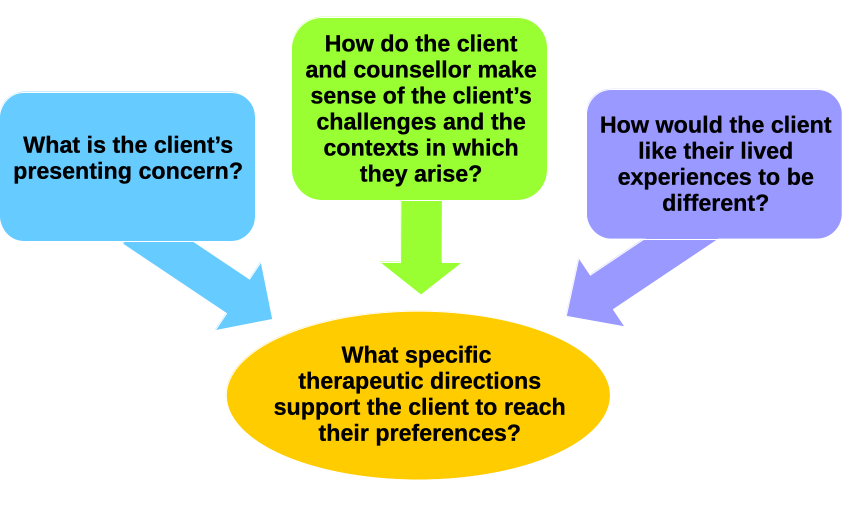

Finally, drawing on the framework for conceptualizing client lived experiences we are using in this book, generate some potential hypotheses for how you would answer the second question in Figure 2 (below): How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise? Of course, at this point these are only tentative wonderments.

Figure 2

Culturally-responsive and social just conceptualization of client lived experiences

Note. Adapted from “Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens,” by S. Collins. In S. Collins, 2018, Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology, p. 581 (https://counsellingconcepts.ca/). Copyright 2018 by Counselling Concepts.

B. Avoiding Premature Foreclosure

One of the risks of maintaining a narrow focus on one domain is premature foreclosure on developing a deep and complete understanding of client lived experiences. This does not mean that you need to, or have a right to, know everything about a client; rather, it means that clients have a right to choose to share with you a full picture of the influences on their presenting concerns. This depth and breadth of understanding opens the door to client-centred counselling processes. It also pre-empts the tendency to jump to conclusions without complete understanding and to move too quickly into considering solutions.

Now that you are more than halfway through this ebook, you may become more inclined toward thinking about change processes. Please resist that urge. We firmly believe that change often occurs from the moment you encounter clients, in particular, in the context of responsive and growth-fostering relationships. However, we purposefully do not entertain more formal change processes or interventions in this resource. Our intent is keep inviting you to focus on listening and relating, and listening and relating, as the best foundation for change.

Conceptualizing client lived experiences: Bio–psycho–social–cultural–systemic considerations

In this next video Sandra replays Anika’s story (from the previous video), pausing periodically to share her own reflections and to introduce areas of inquiry that might support Sandra in more fully understanding Anika’s experience. Notice how the questions Sandra poses move beyond the traditional bio–psycho–social model to embrace the cultural and systemic influences on Anika’s story.

© Sandra Collins (2020, December 22)

Questions for consideration:

- How might expanding on, and building integration across, various domains enhance client–counsellor co-construction of understanding of client challenges?

- Revisit your very tentative hypotheses about the client’s challenges from the previous learning activity. How might you amend, or add to, these in response to the queries Sandra has raised?

- What does this tell you about the importance of continued, in-depth listening and relating as a foundation for co-constructing understanding with Anika?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc14/#CRSJconceptualizing. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

At this point we have introduced all of the counselling microskills we plan to cover in this resource. We will now continue to build your repertoire of techniques to support responsive conceptualization of client lived experience. The Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary provides a quick reference to each of the techniques introduced in this chapter.

A. Techniques

As we noted earlier in the ebook, counselling techniques are intentional linguistic practices that draw on one or more counselling microskills. The techniques we introduce are reflective of a collaborative and co-constructive relational stance, rather than a particular theoretical model, although you can recognize some of the language and processes as emerging from one or more models of counselling (recall the post-modern and constructivist lens we are applying to the counselling process). The appropriateness and relevance of each technique is determined on the basis of client needs, preferences, cultural identities, and contexts, as well as the focus of the counselling process in the moment. These techniques often involve a short sequence of exchanges between counsellor and client aimed at a particular purpose.

1. Linking Domains of Experience

There a number of reasons for including the technique of linking domains of experience. Although we have attempted to isolate feeling and thinking words in our video examples in previous chapters, clients do not naturally make these distinctions. Our intention was to raise your consciousness of the importance of exploring multiple domains and to prepare you to invite clients into deeper consideration of each one. Most often clients mix together affect and cognition as they speak about their issues, or they talk of feelings in particular social contexts, or explain the way they behave when they come up against systemic challenges (i.e., they mix together several domains of experience).

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

As you learn various microskills, the domain differentiation supports your development of proficiency with each skill; however as you become more proficient and confident, many of your reflections and summaries, for example, will not be exclusively feeling-focused or meaning-focused. Or you may move fluidly between domains over the course of a conversation. At this point in your competency development, it is still helpful to maintain a more sequential exploration of the domains.

Integrating the bio–psycho–social domains of experience

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this video Gina supports Sandra in exploring her decision to retire early through the lens of the bio–psycho–social model, focusing first on how Sandra’s health influences this decision (bio), then highlighting the relational implications (social), and finally by drawing forward Sandra’s values (psycho) as a way of shifting into the more intrapsychic domain of thoughts and beliefs.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, May 6)

Questions and prompts for reflection:

- How might you continue to expand on the “psycho” part of the model by exploring further Sandra’s thoughts and beliefs.

- What might you want to know about how other dimensions of Sandra’s identities (cultural) and her experiences with various institutional contexts (systemic) influence this decision?

Linking domains of experience

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In Chapter 6 Sandra explored with Gina her desire for balance in her life, focusing on Gina’s thinking (i.e., beliefs, values, priorities). Notice how Sandra shifts the domain of experience first by inviting Gina to consider the sociocultural context of her challenge then by inviting Gina to consider other contexts of her life. Gina introduces her professional writing as a second domain (cognitive), and Sandra invites consideration of self-care practices (actions). This video is a bit longer (12 minutes) as we provide an example of making connections across multiple domains.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 20)

Sandra used a variety of microskills from previous chapters to support the overall technique of linking domains of experience. Notice that Sandra started one of her questions with “Do you . . .” which might lead to a yes/no response and be considered a more closed microskill (i.e., clarifying). However, Gina picks up on Sandra’s query as if it was the more open questioning microskill (i.e., she responded to the intent, not the specific language). How might you word this question to be more open?

Notice how, by building links across various domains, Sandra is able to query with Gina the differences in her lived experiences across these aspects of her lived experience. This leads to some insight on Gina’s part that supports shared meaning-making. If you were going to continue this conversation with Gina, what other domains of experience might you introduce for her consideration.

As you gain proficiently with the microskills introduced in the previous chapters, you will gain fluency in moving between various domains of client experience. This fluency is even more important as you begin to work with clients in practicum or professional practice settings.

Thick Description

The techniques in Chapters 7, 8, and 9 are grounded in counsellor–client co-construction of rich descriptions of client challenges across multiple dimensions of experience. Paré (2013) contrasted thick descriptions with an individualist perspective that locates both client challenges and potential solutions within the decontextualized individual (i.e. within their thinking, feeling, or behaving). In essence a thick description is a detailed, multidimensional, shared understanding of the challenge the client is facing as well as the context in which it arises. Reflect back on the two videos above that demonstrated linking domains of experience. Consider what assumptions or hypotheses may have emerged about Gina and Sandra’s challenges (as the clients) if the conversation had ended without considering additional contexts for their challenges or exploring their lived experiences in other domains.

Paré (2013) also encouraged counsellors to avoid the use of labels, particularly diagnostic labels that necessarily constrict meaning and essentialize problems. You may encounter clients who already have labelled themselves or adopted labels from their experiences in healthcare systems. Even where these labels pre-exist, it is important to invite clients into conversations that permit them to explore openly the meaning they make of the experience of being labelled and the label itself. The antithesis of abbreviated labels is the thick, rich, multilayered, contextualized, insider information that emerges from collaborative co-construction of meaning.

2. Making Hypotheses Transparent

Through the process of exploring client challenges in collaboration with them, you will begin to develop a client-centred understanding of what they would like to change in their lives. So: How do you know when you have come to a complete enough shared understanding of the challenge the client currently faces? As you move into making your hypotheses transparent, it is often helpful to offer up a fairly succinct statement of how you are perceiving the client challenge. Through your use of reflecting both meaning and feeling, and summarizing, you continuously share what you are thinking with clients. However, how you are putting those pieces of information together into hypotheses about client challenges may not be clear to clients. At some point it will be important to make those hypotheses more transparent for client consideration, reflection, or revision. In some cases, a name or linguistic tag emerges from the dialogue that signifies to both counsellor and client a shared understanding of the challenge (e.g., dilemma, perfectionism, being stuck, the self-critic). These metaphors (see Chapter 6) or summary statements may provide a synthesis of the conversation that offers a response, at least in the moment, to the key question: How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise? (see Figure 2 above).

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Making hypotheses transparent

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In the video below Gina picks up on her earlier conversation with Sandra about the choice to retire early. She begins by explicitly sharing her developing hypothesis with Sandra. Notice how she also provides an explanation of what she is doing, drawing on the skill of transparency.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, June 6)

Reflections:

- What might it be like for you to share with clients your hypotheses as they begin to form?

- What hesitations do you experience in being transparent with clients in this way?

- How might you do this tentatively and in a way that invites client feedback?

Making hypotheses transparent: Testing and refining hypotheses

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

Sandra starts this video off by sharing her current hypothesis with Gina:

There are things in Gina’s life she wants to increase (self-care, exercise, time with family and friends) and there are things she might need to decrease (availability to clients, evening work). But the temptation is to move things around without actually reducing overall demand, which might not open up the space for balance in the way Gina is hoping.

Notice how Sandra is transparent about owning her own idea (hypothesis). She summarizes what Gina has shared and then uses self-disclosing (i.e., sharing what is going on in her own thinking process) to open conversation about her current hypothesis.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, June 6)

Reflections:

- How did Sandra’s use of self-disclosure in this video support her intent to make her hypotheses transparent?

- What other microskill did Sandra use repeatedly in this segment to ensure that she was on the right track in terms of her hypotheses?

- Sandra reminds Gina of the language of “good enough” (from Chapter 6 videos). How did reintroducing this metaphor for balance help shape Gina image of what balance might look like?

- How does inviting Gina to explore further her personal meaning related the “perfectionist” help ensure they are co-constructing a shared hypotheses about the challenge Gina is facing?

- By the end of this conversation, Sandra refines her hypothesis and shares it with Gina. How did Sandra’s choice to make her hypotheses transparent at the beginning, middle, and end of this conversation support the overall goal in this chapter of relating in client-centred and culture-centred ways?

- What might you have done differently in this conversation?

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

1. Enhancing Cultural Intelligence

Cultural intelligence (CQ) capabilities

Contributed by Ana Azevedo

In my video earlier in the chapter, I introduced four cultural intelligence (CQ) capabilities. Take a moment now to apply each of them to the principle of adaptability to client-centred practice.

- Reflect back over the content of the chapter, and imagine one or two intercultural situations in which you might struggle to adjust automatically to the cultural cues from clients or their stated desires (e.g., a client including family members in the session; a client foregrounding values you do not share or understand).

- Identify one or two specific areas in which you might be inclined to be less flexible and adaptive to client needs or inclinations, within the broad umbrella of counselling activity, therapeutic approach, or therapist characteristics (e.g., adapting your model of counselling; responding to a client request for direct advocacy).

- Then list one or two possibilities for how you might improve your CQ as a foundation for enhancing your adaptability, using the table below. Click here for the Word version or the PDF version. Treat this like a brainstorming session in which you write down whatever comes to mind without evaluation or commitment to action.

| CQ Capabilities (by Ana Azevedo) |

My CQ goals (Adaptability to client-centred practice) |

| Motivation (interest, confidence, drive) | 1.

2. |

| Knowledge (understanding of cultural similarities and differences) | 1.

2. |

| Strategy/metacognition (ability to plan, be aware, and make sense of intercultural situations) | 1.

2. |

| Action/Behaviour (ability to adjust verbal and nonverbal behaviours in intercultural situations) | 1.

2. |

- Finally, choose one or two actionable goals that you can realistically embrace this week. Be as specific as possible about how you will go about working toward those goals.

The key to enhancing your CQ and adaptability skills is practice, practice, practice. I encourage you to revisit the goals you identify, choosing others to work on at a later time.

2. Enlisting Your Own Story

As you reflect on your own evolving story, use the following questions and prompts to review concepts, principles, and practices introduced in this chapter as well as to refine your understanding of the challenge you are facing.

- You play the role of both counsellor and client for your own story as you personalize, and make meaning of, what you are learning throughout this ebook. If you lean into the client perspective, for a moment, what resonates for you in terms of your preferred activities, approach, and therapist characteristics?

- Are these the same inclinations you would have expressed ten years ago, five years ago, or prior to reading this ebook? If not, what does the fluidity of your perspectives suggest about how to approach assessment of client views as a counsellor?

- As you reflect on your exploration of your story from Chapter 1 to Chapter 6, what do notice about the domains of experience that rose to the surface for you? What areas remain less examined? What meaning do you make of that? Take a few minutes to reflect on the domains where you have developed a less thick description of your experience? What emerges that might enhance your understanding of the challenge you face?

- Take a moment to write down 2–3 potential hypotheses that you might use to describe the crux of your challenge to someone else. You may even try them out on a friend or family member to see how succinct you can be while still capturing the challenge in meaningful way. Practice saying each of these to yourself to see which one seems to be provide the best fit, or modify one that seems closest to your lived experience at this moment.

- Pay attention, as you move through the remaining chapters of the ebook, to how enduring that hypothesis is.

Remember, we are presenting an incremental model for building responsive relationships and working with clients to conceptualize their lived experiences. However, the counselling process rarely moves in a linear fashion: typically you will move in and out of various activities; certain themes can come to the foreground then recede new challenges emerge; and you may revisit earlier conversations.

3. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Macey’s story Part 7

As you reflect on Part 7 of the story of Macey, consider what you have learned about counsellor style in this chapter.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, April 8)

Consider Macey’s preferred styles of interaction with her counsellor. How might you adapt your counselling style with Macey in response to this information?

As a way of responding to Macey’s story this week, and in particular her request for advice about coming out, Gina Ko introduces the split opinion approach to providing clients with feedback. You are invited to take up one of the opinions to present to Macey through the video below.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 19)

Now take a moment to reflect back on what you have learned about Macey over the past seven installations of her story. What hypotheses have you considered about Macey’s challenge? Which ones might you toss out altogether? Which might you refine in collaboration with Macey at this point?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

For the applied practice activities in this chapter, we draw on a variety of microskills from previous chapters to support you to develop a thick, multidimensional, and client-centred understanding of client challenges. You may want to print out the applied practice activities before you begin your practice session.

A. Responsive Techniques

Preparation

You can bring forward the story you have been working on as part of the Reflective Practice in each chapter, or you can identify a different challenge you are currently facing on which to draw for each of the applied practice activities (below). Try to choose a challenge that is complex and multidimensional in nature to give your peer partner an opportunity to practice exploring multiple domains of experience and generating tentative hypotheses.

1. Warm-Up Activity: Thick Description (20 minutes)

The purpose of this activity is to co-construct of a thick description of client challenges.

Preparation

Revisit the explanation of thick versus thin descriptions (under Linking Domains of Experience earlier in the chapter).

Skills practice (4–5 minutes each)

Provide each other with a brief summary your challenges, so that you have a starting place for these conversations and can move more quickly into in-depth exploration.

- Client: Talk about your challenge(s), focusing on either thoughts or emotions.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on whatever microskills are useful in the first few minutes to engage the client in dialogue about their thoughts or emotions, following the client’s lead about the domain of experience.

- Then introduce reflecting meaning or reflecting feeling, focusing on contributing language, metaphor, or inference to support a thicker shared understanding.

- After about 4 minutes use the microskill of summarizing to pull together what you have learned about the client’s challenge so far.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide each other with feedback on the ways in which specific microskills or language choices helped to thicken the description of the client’s challenge.

- Reflect together on the degree to which each summary resonated for the client.

2. Linking Domains of Experience

(1 hour)

Note. If you followed the client’s lead into the cognitive domain in the warm-up activities then start with skills practice A; if you started off in the affective domain, begin with B. Then continue directly to explore the other domain. Each person should complete both A and B as well as C before you switch roles. By extending the time, you will have more opportunity to explore the challenge presented in greater depth and breadth.

A. Skills practice thoughts and beliefs (9–10 minutes each)

Continue to thicken your understanding of the challenges you are each facing as you practice linking domains of experience.

- Counsellor:

- Begin by reworking your summary from the previous practice activity, attempting to come closer to the client’s perceptions of the challenge. If you completed B first, then use the skill of providing transparency to signal a change of focus to the cognitive domain.

- Then draw on reflecting meaning and, where appropriate, perception checking to pick up on portions of the conversation that seem most meaningful to the client. Integrate other microskills as appropriate.

- Look for opportunities to introduce metaphoric language for the client’s consideration through continued use of reflecting meaning.

- Client: Respond as naturally as you can to the conversational flow, assisting your peer partner by keeping your focus on the cognitive domain.

- Counsellor:

- Continue to draw on the microskill of reflecting meaning to work with the client to refine the emergent metaphor or shared language in a way that is most meaningful and helpful to them.

- Then offer another summary, attempting to move closer to a shared understanding of the client’s challenge.

B. Skills practice emotions and sensations (9–10 minutes each)

Continue to thicken your understanding of the challenges you are each facing as you practice linking domains of experience.

- Counsellor:

- Begin by reworking your summary from the previous practice activity. If you completed A first, then use the skill of providing transparency to signal a change of focus to the affective domain.

- Then draw on reflecting feeling and, where appropriate, perception checking to pick up on portions of the conversation that seem most meaningful to the client. Integrate other microskills as appropriate.

- Client: Respond as naturally as you can to the conversational flow, assisting your peer partner by keeping your focus on the affective domain.

- Counsellor:

- Look for opportunities to introduce one of the following additional skills to thicken your understanding of client affect and embodiment: inviting embodiment, providing immediacy.

- Then offer another summary, attempting to move closer to a shared understanding of the client’s challenge.

C. Synthesis across domains

- Counsellor:

- Try summarizing what you have learned so far, pulling together key themes from the affective and cognitive domains. Remember still to keep your summary as succinct as possible.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How challenging was it to extend the length of time for your skills practice?

- Take turns inviting feedback from each other about the moments that were most helpful and meaningful from the client perspective. Use your microskills to solicit feedback as you would if you were still in a counselling session with the client.

- How did these significant moments align with your experience or observations in the role counsellor?

3. Expanding Domains of Experience

(30 minutes)

Skills practice (9–10 minutes each)

Choose one additional domain of experience to focus on in this next segment: biological, behavioural, or social. Decide together whether the client or the counsellor will introduce the new focus to explore the same challenge.

- Counsellor or client: Introduce the shift in domain focus.

- Counsellor:

- Use a combination of any two of these microskills or techniques: reflecting meaning, exploring inconsistencies, checking perceptions, co-constructing language to invite deeper understanding of the client’s lived experience.

- Client: Respond as honestly and openly as possible.

- Counsellor: Periodically use summarizing to focus attention on what you perceive to be the most relevant themes, language choices, metaphors, and so on.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Reflect together on how adding an additional dimension to the conversation produced a thicker description and enhanced your shared understanding?

4. Making Hypotheses Transparent

(1 hour)

You have likely already been sharing your hypotheses with each other through the summaries you have generated in each of the previous applied practice activities. We now invite you to make your hypotheses more transparent to the client, offering them in respectful, client-centred, and tentative ways. Be sure to avoid language that is theory-driven, even if your theoretical orientation influences how you are thinking about the client’s challenge.

Skills practice (9–10 minutes each)

As you move towards expressing hypotheses about the challenge(s) the client is facing, you will often be drawn back into the domain of thoughts and beliefs. Feel free in this activity, however, to also draw on elements of the other domains you explored.

- Counsellor:

- Begin by attempting again to summarize what you have learned so far about the client’s challenge. Be explicit, but tentative, about posing this as a hypothesis that has developed as you talked together. Follow this with an explicit invitation for the client to provide feedback using the microskill of perception checking.

- Then draw on reflecting meaning to come closer to a shared understanding of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise. Integrate other microskills as appropriate.

- Client: Respond as naturally as you can to the conversational flow.

- Counsellor:

- Continue to draw on the microskill of reflecting meaning to work with the client to co-construct a hypothesis that is meaningful and helpful to them.

- Offer another summary, attempting to state the emergent hypothesis as clearly and succinctly as possible.

After you have each complete one round of this process, repeat it to see if you can come closer to answering the key question: How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise? (Figure 2). This time start by making the emergent hypothesis transparent without explicitly stating what you are doing.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How did the two techniques, integrating domains of experience and making hypotheses transparent, support you to conceptualize the client’s lived experiences more clearly?

- In what ways were you able to stay client-centred and to attend to client perspectives throughout the skills practice? In your role as clients, what preferences might you voice at this point that could influence the counsellor’s approach to working with you?

- As the counsellor, reflecting back on the skills practice activities, where might you have tapped into an opportunity to assess client needs and perspectives or to adapt your style to suit this particular client?

REFERENCES

Bemak, R., & Chung, R. C. (2015). Critical issues in international group counseling. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 40(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2014.992507

Collins, S. (2018a). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices: Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 441–505). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018b). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Exum, H. A., & Lau, E. Y. (1988). Counseling style preference of Chinese college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 16(2), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.1988.tb00644.x

Fellner, K., John, R., & Cottell, S. (2016). Counselling Indigenous peoples in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 123–147). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Ginsberg, F., & Sinacore, A. L. (2015). Articulating a social justice agenda for Canadian counselling and counselling psychology. In A. Sinacore & F. Ginsberg (Eds.), Canadian counselling and counselling psychology in the 21st century (pp. 254–272). McGill-Queens University Press.

Kassan, A., & Sinacore, A. L. (2016). Multicultural counselling competencies with female adolescents: A retrospective qualitative investigation of client experiences. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 50(4), 402–420. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/

Kim, B. S., & Park, Y. S. (2015). Communication styles, cultural values, and counseling effectiveness with Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(3), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12025

Nitza, A. (2017). To a classroom in Botswana (and back) in search of cultural understanding. Social Work with Groups, 40(1–2), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2015.1079689

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Paré, D., & Sutherland, O. (2016). Re-thinking best practice: Centring the client in determining what works in therapy. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling and Psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 181–202). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Parrow, K. K., Sommers-Flanagan, J., Cova, J. S., & Lungu, H. (2019). Evidence-based relationship factors: A new focus for mental health counseling research, practice, and training. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.4.04

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice competencies. Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development, Division of American Counselling Association: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=14

Roysircar, G., Studeny, J., Rodgers, S. E., & Lee-Barber, J. S. (2018). Multicultural disparities in legal and mental health systems: Challenges and potential solutions. Journal of Counseling and Professional Psychology, 7(3), 34–59. http://www.thepractitionerscholar.com/index

Swift, J. K., Callahan, J. L., Cooper, M., & Parkin, S. R. (2018). The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 1924–1937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22680

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://nctr.ca/records/reports/

Willis-O’Connor, S., Landine, J., & Domene, J. F. (2016). International students’ perspectives of helpful and hindering factors in the initial stages of a therapeutic relationship. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 50(3, Supplement), S156–S174. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/

Woodend, J., Nutter, S., Lei, D., & Cairns, S. (2016). Exploring the experiences of international students’ partners: Implications for the post-secondary context. In K. Bista & C. Foster (Eds.), Exploring the social and academic experiences of international students in higher education institutions (pp. 96–114). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-9749-2.ch006

Zakaria, N. (2017). Emergent patterns of switching behaviors and intercultural communication styles of global virtual teams during distributed decision making. Journal of International Management, 23(4), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2016.09.002