Listening to Self

3.1 Listening to Self as Awake, Aware, Conscious

To be awake, enlightened, and fully conscious is not the typical response most people provide to the question, “Who are you?” Yet, consciousness is an essential part of our human nature. Paraphrasing medical doctor and researcher Larry Dossey, “awakedness” is pure awareness, consciousness, part of the Big Self, the Great Spirit, the universal mind.[1] Dossey provides evidence from ancient and modern sources that we are more than our individual minds, that we are part of One Mind.[2] Our conscious awareness is beyond the limits of the body, personality, memory, beliefs, feelings, social roles, and genetics. A greater understanding of this awakened aware consciousness is essential to understanding what it means to listen to the self in the SONG of life.

Wheel of Self Awareness Listening Meditation

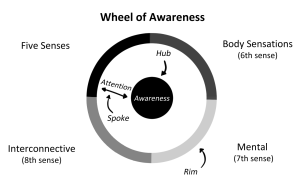

The importance and relevance of listening with our conscious awareness is illustrated by Daniel Siegel’s “Wheel of Awareness.”[3] The wheel is a method to link the different elements of the content of awareness into an integrated whole. The hub of the wheel represents what we can know within awareness. The spokes that go out from the center of the wheel represent our conscious focus of attention as represented by areas or sectors on the rim of the wheel. The sectors are divided into various “senses.” The five senses are the outer world, the sixth sense is the body, the seventh sense represents mental activity, and the eighth sense symbolizes relationships. Finally, awareness can “bend back” on itself, aware of the feeling of awareness.

Wheel of Awareness Practice

Allowing awareness to follow along the rim of Siegel’s wheel of awareness is a meditation in listening to the self. In the wheel of awareness meditation, each sector of the self on the rim is reflected on in turn. In this process of listening, the various aspects of self are integrated into a coherent whole. After completing the wheel of awareness meditation, Siegel recommends reflecting on additional questions for further understanding:

How did it [our awareness on any point of the wheel] first come into awareness? Does it come suddenly or gradually? . . . once it is in awareness, how does it stay there? Is it constant or vibrating, is it steady or intermittent? And then how does it leave awareness? Suddenly, or gradually, or . . . if it is not replaced by another mental activity, what does the space feel like between two mental activities . . . [4]

Practicing the wheel of awareness meditation, and reflecting on the post meditation questions, provides a deep engagement of listening to the self in the SONG of life.

Listening to Self with Open Focused Attention

Les Femi and Jim Robbins present another perspective of the self using the language of attention. Conscious awareness consists of attention, the contents of attention, and the witness of both.[5] When brain activity between attention and its contents is “out of phase,” self is experienced as separate from the contents of attention.[6] Whereas, when brain activity is “in phase,” the experience of a unified whole emerges, and the self becomes “unself-conscious,” that is, the sense of self “disappears.”

The quality of attention called “open focus” allows the self to hold different forms of attention, narrow and diffuse, and objective and immersed. It is possible for the self to hold these different forms of attention simultaneously while also maintaining a flexibility to shift focus depending upon on the situation and intention.[7] Open focus is an inclusive attention style that takes in multi-sensory information simultaneously. Femi summarizes the profundity of an open focus approach to attention, “When we change the way we pay attention, we gain the power to profoundly change the way we relate to our world on every level–physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually.”[8]

Open Focus Awareness

One way to begin cultivating an open focus sense of self-awareness (to listen to self) is to imagine “feeling responses” that spontaneously emerge from your responses to the following questions (it is recommended to pause for fifteen seconds after each question):

Can you imagine the distance or space between your eyes?

Can you imagine the space inside your throat as you inhale?

Can you imagine the space inside your mouth and cheeks?

Can you imagine the space inside your ears?[9]

I view the cultivation of open focus attentional practices as another “listening to self” meditation that, like the wheel of awareness practice, expands, develops, and fosters a greater sense of self.

Listening to Self as an Energy House

Victor Pierau uses the image of an “energy house” for understanding self-awareness and its relationship to listening.[10] Picture the energy house as a circle divided into four pieces of pie labeled physical, emotional, mental, and “purpose or spirituality,” with our personality as a smaller circle in the center. By paying attention to each of these areas within ourselves (i.e., listening to these aspects of the self), we can gauge how much energy the self has available for listening to others.[11]

Energy Keeping Practices

Pierau provides practical “energy keeping” insights for each of the four areas of the energy house that I paraphrase here.

Take in fresh air and sunlight to support energy in the physical area of the energy house.

Take short breaks regularly to stay mentally alert.

Reflect on your emotional reactions to others for the emotional area of the energy house.

Work towards meaningful goals for the spiritual area.

All four quadrants of the energy house, physical, mental, emotional, and purpose-spiritual are part of listening to self in the SONG of life.

From Ego to Kosmic Perspectives of Listening to Self

Wilber and colleagues[12] provide another perspective on self-awareness that begins with ego and ends with the Kosmic level of awareness. The ego-centric focus on “me” is the self-absorbed state of consciousness. The next level, called ethnocentric, is the identification with a particular group, tribe, clan, or nation. Another level up, worldcentric consciousness expands self-identity to include all humans. Finally, the highest level of development, encompassing an identification with, and caring for, all sentient beings is called Kosmocentric. Self-awareness potentially contains ego, ethno, world, and Kosmo centric levels of consciousness.

Within these states of self-awareness, there are lines of development that can be depicted on an integral psychograph.[13] This graph includes several crucial areas of self-awareness and development including cognitive lines, self-related lines (e.g., needs, morals), talent lines (e.g., music, spatial, mathematical), and spiritual, aesthetic, emotional, psychosexual, and interpersonal lines.

Increasing Awareness of Developmental Lines Practice

One activity to heighten awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of our developmental lines is to consider our responses to the following questions:

-

- What am I aware of (cognition)?

- What do I need (needs)?

- Who am I (self-identity)?

- What is important to me (values)?

- How do I feel about this (emotional)?

- What is beautiful or attractive to me (aesthetics)?

- What is the right thing to do (moral)?

- How should I interact (interpersonal)?

- How should I physically do this (kinesthetic)?

- What is of ultimate concern (spirituality)?[14]

Responding to and reflecting on answers to these questions is engaging in and cultivating a greater awareness of and listening to self in the SONG of life. As a protocol, one could write each question at the top of a page, representing one question daily to meditate on. On the first day, the first question, repeat the question several times silently and/or aloud to establish a firm intention. Then, sit comfortably, breathe easy, and let the mind percolate responses to the question. All you need do is allow the process to unfold by observing the responses, and when you are distracted, gently return to the question by silently repeating the question. After whatever time you have allotted for the meditation, you can journal your responses. I encourage you to note one insight that might be testable in your everyday life. Devise a small test to carry out sometime during the day. At the end of the day, note the results of your test, including if you would like to repeat the test with some variation. When you feel satisfied with the outcome, proceed to the next question. Through this process across the days/weeks, you develop a keener awareness of how listening to the SONG of life applies to the unique personal circumstances of your own life.

Listening to the Authentic Self

What is the authentic self, and is it possible to listen to it? Julia Mossbridge[15] conceptualizes the individual as having conscious, unconscious or subconscious, and superconscious minds, and a body. The conscious mind is, “. . . a linear, serial-processing logical system that maxes out at four factors . . .” whereas the subconscious mind, “. . . [is] a nonlinear, parallel-processing system that routinely deals with multiple factors and presents its results to the conscious mind without an explanation.” The superconscious mind is the, “. . . source of our connection with the universe . . . [where universe] includes everything that exists . . . [and has] three critical features: inclusivity, connectivity, and autonomy.” All of these aspects of the mind working together to direct our life is the “authentic self.”

Listening to the Authentic Self

Mossbridge provides a “listening experiment” to invite individuals into relationship with these three aspects of our authentic self by filling in the blanks for the following starter statements:

I love to…

I feel best when…

I remember being excited about…

These days, I am learning how to…

I hope it’s not arrogant to believe that I can…

It’s probably not unique, but I think my calling might be related to…[16]

To experiment with this listening practice, one may copy and paste this set of questions into a document representing six consecutive days (six sets of questions, one for each day). At a time of your choosing (mid-day, evening, or end of day), briefly record your gut-level responses to the questions without much conscious reflection. Review your responses for the six days for each question separately on the seventh day. See if you note any patterns across the days for each question. What do the patterns reveal about how well you are listening to the SONG of life? In what ways are you growing? How might you improve? Try the same activity in a few months and compare results to see how well you cultivate the ability to listen to your authentic self.

Defining Self Depends On Where You Are

Thus far in listening to the self in the SONG of life, I described several perspectives of the “self” along with activities[17] designed to develop the capacity to listen to the self. One theme among all the perspectives of listening to the self is that they depend on “where you are.” The Youniverse Explorer is a model demonstrating how the sense of self changes depending on “where you are” as an observer in the Youniverse Explorer.[18] Beginning with the physical body, it is possible to metaphorically drill down to smaller layers of the self within the body. There is the body’s skin, organs, cells, molecules, and atoms. Smaller than the parts of the atom, there is nothing discernable from current scientific instrumentation. The body’s tiniest basic unit of matter remains a mystery! Conversely, the process can be reversed. We can travel back up to the physical body level defined by its physical outward features such as height, weight, and skin tone. From here, it is possible to travel further outward (upward), away from the body, by powers of ten meters.[19] Eventually, we imagine ourselves on earth viewed from the perspective of the moon, stars, Milky Way, farther galaxies, and to the edge of the known universe beyond which is a mystery.

From these micro and macro viewpoints in the Youniverse Explorer, the self appears to be contracting and expanding in relation to the center of the witnessing observer. As an observer, Lang notes that there exists a silent void or space from which the person is observing.

Lang provides a simple experiment to demonstrate this phenomenon, which I describe as follows:[20] Standing or sitting, notice that you cannot see your own face. From your first-person perspective, looking out at the world, you are headless! If you hold your hands out in front of you, clearly, they are there. But if you move your hands slowly back behind your head, your hands “disappear” into the great void, the empty space, the silence. When you bring your hands forward again, the hands arise from the void. Lang describes our “self” as this, “. . . void, the Great Space, Emptiness, the True Self, the Openness here, this Clarity, Stillness, the place I am looking out of, my No-face, my No-head.” This is the private identity that we have for ourselves. It is the core of the self. The self of the SONG of life that we are learning to listen to when we contract and expand ourselves in the Youniverse Explorer.

- Larry Dossey, One Mind: How Our Individual Mind is Part of a Greater Consciousness and Why it Matters (Carlsbad: Hay House, 2013). ↵

- Larry Dossey, One Mind, 2013. Some of the ancient sources Dossey draws on are Buddhism, Christianity, Upanishads, Hermes Trismegistus, and for modern sources he relies on Richard Maurice Bucke, William James, Carl Jung, Erwin Schrodinger, Ken Wilber, Huston Smith, Davide Bohm, Rupert Sheldrake, Lynne McTaggart, Ervin Laszlo, Dean Radin, Stephan A. Schwartz, Charles Tart, and Russell Targe, among others. ↵

- The wheel of awareness is a meditation practice that highlights the central nature of self-awareness as it links to many parts of the self. Daniel J. Siegel, Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology: An Integrative Handbook of the Mind (New York: W.W. Norton, 2012), 26-1 through 26-8. ↵

- Daniel J. Siegel, Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher-Tenguin, 2013), 135. ↵

- Les Femi and Jim Robbins, The Open-Focus Brain: Harnessing the Power of Attention to Heal Mind and Body (Durbin: Trumpeter Publishers, 2007). ↵

- The neuro brain language of "phase synchrony" described by Femi is somewhat technical. One helpful image for understanding the ideas of "in and out of phase activity" is to consider a group of singers. When the singers are singing in harmony, they are "in phase," whereas when the singers are singing in different keys, they are "out of phrase." ↵

- Les Femi and Jim Robbins, The Open-Focus Brain, 2007, 46-54. There are two dimensions (narrow-diffuse, and objective-immersed) that make up four quadrants of attention in the open focus system. As an illustration, narrow attention is defined as concentration on a limited field of experience (e.g., visually, a single point in the field of experience with no attention to the periphery) while diffuse focus is a more inclusive and softer kind of attention (e.g., visually, gazing at a landscape). ↵

- Les Femi and Jim Robbins, The Open-Focus Brain, 2007, 5. ↵

- These questions are a sample of an open focus guided meditation from Les Femi and Jim Robbins, The Open-Focus Brain, 2007, 64-65. ↵

- Victor Pierau, Leadership in Listening: The 7 Levels of Listening for Professionals (Hilversum: Booklight Makkum, 2020). Pierau attributes the origins of the energy house to "Native Americans of the old America." He does not specify the characteristics of an energy house except that it is circular. Historically, people of the current North American continent built many types of houses that have a circular arrangement, including tepees, earth and grass houses, wattles, and igloos. See Native American Houses (website), 1998-2020. http://www.native-languages.org/houses.htm. ↵

- While Pierau defines "others" as other humans, I define "others" more broadly to include other people, nature, the Divine, and ourselves. ↵

- Wilber et. al., Integral Life Practice, 2008. ↵

- Wilber et. al., Integral Life Practice, 2008, 81-85. Wilber et. al. consider developmental lines as, ". . . many kinds of 'smarts' available to us . . ." each relatively unique and independent of the other lines. The levels of consciousness are like "fluid waves" while the developmental lines are like "sinuous streams." ↵

- Wilber et al., Integral Life Practice, 2008, 86. ↵

- Julia Mossbridge, The Calling: A 12-week Science Based Program to Discover, Energize, and Engage your Soul's Work (Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, 2019), 12, 35, 132. ↵

- Julia Mossbridge, The Calling, 2019, 35-36. Mossbridge suggests conducting this listening experiment several times a day for a week to look for patterns in the inner workings of the three types of mind operative in the authentic self. ↵

- The activities are Siegel's Wheel of Awareness, Femi's Open Focus, Pierau's Energy House, Wilber's Levels of Consciousness and Lines of Development, and Mossbridge's Authentic Self. ↵

- Richard Lang, Celebrating Who We Are (London: The Shollond Trust, 2018). Richard Lang is a student of Douglas Harding. The Youniverse Explorer is an invention of Douglas Harding, described in further detail by Lang and paraphrased here. ↵

- Powers of ten refers to scientific notation where any number can be expressed mathematically as a power of ten. For instance, the number 10 is expressed at 101, and 100 is 102 while .10 is 10-1, and so forth. A visually stunning video of these powers of ten models the inward and outward processes of Harding's Youniverse Explorer. Charles Eames and Ray Eames [writers and directors]. Powers of Ten. Pyramid Films. September 4, 1977. See also Philip Morrison, Phylis Morrison, Charles Eames, and Ray Eames, Powers of Ten: About the Relative Size of Things in the Universe (New York: Scientific American Books, 1990). ↵

- Richard Lang, Celebrating Who We Are, 2018, 6. ↵