11

Katie Dzoba

Can Being Obese While Pregnant Affect the Baby?

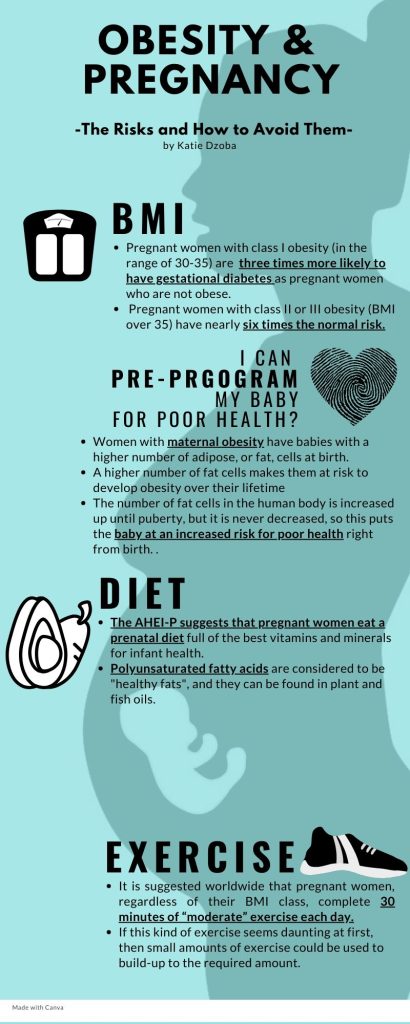

All pregnant mothers want their babies to be born as healthy as possible, and most parents want to know the health risks that their children will have and ways to reduce those risks. However, maternal obesity is often overlooked as a threat to the health of a newborn baby even though it is one of the biggest factors that will determine newborn and infant health. Being obese while pregnant leads to poorer outcomes for the baby such as preterm birth and being “programmed” for poor health in the future. Luckily, there are many ways to reduce these risks. For example, a complete diet and regular exercise are simple ways to start lowering these risks.

What are the Classes of Maternal Obesity?

To learn what qualifies as maternal obesity, it is important to assess a woman’s BMI. BMI, or body mass index, is a measure that relates height to weight, and it can be used to qualify the different classes of obesity. Class I obesity is a BMI in the range of 30-35, class II obesity is in the range of 35-40, and the worst level health-wise is class III obesity which is any BMI over 40. Women with class I obesity have three times the risk of having gestational diabetes as pregnant women who are not obese, and women with class II or III obesity have almost six times that risk (Slack et al., 2019). Because of maternal obesity, many factors come into play that can put the newborn baby at risk.

What Risks are Involved with Maternal Obesity?

Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that is developed during pregnancy and causes high blood sugar. It increases the risk of preterm and post-term births and puts babies at risk for serious issues with their health during the first few weeks of life. Gestational diabetes can also throw off hormones found in the placenta which is the protective casing around the baby in the womb. Without those hormones available to the baby, the baby is put at risk for neurodevelopmental disorders that impact their ability to learn, show emotions, and use self-control as he or she matures (Murthi & Vaillancourt, 2020). Examples of neurodevelopmental disorders include ADHD, autism, learning disabilities, cerebral palsy, etc.

Maternal obesity can also “pre-program” a baby to have issues with their own health and weight in the future. As of 2012, 31.8% of obese women fell into the age range of 20-39, which is the best time to have a baby according to fertility research (Johns et al., 2020). Babies who are born to mothers with maternal obesity have a higher number of adipose, or fat, cells at birth as well (Wang et al., 2020). This makes them more likely to develop obesity over their lifetime because the number of fat cells in the human body increases up until puberty but never decreases. After puberty, when someone gains weight, fat cells increase in size but not in number, so a baby born with a high number of fat cells is already one step closer to poor health because of the mother’s obesity. This risk of obesity for the child also puts him or her at a higher risk for developing diabetes, heart disease, and strokes which are all diseases that tend to co-occur in patients with obesity (Johns et al., 2020). To learn more about comorbid conditions of obesity visit Comorbidities of Obesity. By being obese while pregnant, women are setting their children up for many health risks during their lifetime.

How Can the Risks be Reduced?

Diet

Luckily, there are ways to reduce these risks if healthy behaviors are adopted before or during pregnancy. In 2012, pregnant women in the United States only scored 50.7 points out of a possible 100 on the Healthy Eating Index which measures diet quality. This is eight percent lower than the score for an average adult in the United States. Because the amount of pregnant women who eat healthily is less than it should be, the Alternative Healthy Eating Index for Pregnancy, or AHEI-P, is now used to recommend healthy eating habits. The AHEI-P puts sweetened beverages, red/processed meats, trans fats, and sodium in its four categories that should be eaten only in moderation. However, AHEI-P has nine other categories of foods that should be eaten frequently. These categories include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts/legumes, polyunsaturated fatty acids (healthy fats), iron, folate, and calcium (Parker et al., 2019). Polyunsaturated fatty acids are considered to be “healthy fats”, and they can be found in plant and fish oils. The AHEI-P suggested foods are important to have in a prenatal diet to make sure the mother gets the best vitamins and minerals for infant health. When talking to a doctor, diet improvements are a crucial first step in reducing the risks associated with maternal obesity.

Exercise

Another way to reduce risks posed by maternal obesity is through regular exercise. It is suggested worldwide that pregnant women, regardless of their BMI class, complete 30 minutes of “moderate” exercise each day. However, the most recent data shows that only 15.8% of pregnant women meet this requirement (Flannery et al., 2019). If this kind of exercise seems overwhelming at first, then small amounts of exercise could be used to build-up to the required amount. 150 minutes of total exercise per week should be the overall goal, but that exercise can be built up by simply working out a few minutes each day during the week (Simon et al., 2020). For a video that includes specific examples of simple exercises to do throughout pregnancy, click on the image to visit the link titled, “Exercises To Do During Pregnancy.”

Summary

With the risks of maternal obesity in mind, parents can make healthy lifestyle choices before they decide to try to have a baby. Those healthy lifestyle changes can be as simple as mindfully eating a nutrient-dense diet or taking a small part out of each day to get the suggested amount of exercise per week. Making small changes to a daily routine or diet can greatly reduce health risks for the baby and allow parents to give their children the best chance at a healthy life right from birth. To learn more about nutrient-dense foods, see Food and Calories. The following infographic can be used to review the concepts presented in this chapter.

Review Questions

References

Flannery, C., Fredrix, M., Olander, E. K., McAuliffe, F. M., Byrne, M., & Kearney, P. M. (2019). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for overweight and obesity during pregnancy: A systematic review of the content of behavior change interventions. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 16(1), N.PAG. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1186/s12966-019-0859-5

Johns, E. C., Denison, F. C., & Reynolds, R. M. (2020). The impact of maternal obesity in pregnancy on placental glucocorticoid and macronutrient transport and metabolism. BBA – Molecular Basis of Disease, 1866(2), N.PAG. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.12.025

Murthi, P., & Vaillancourt, C. (2020). Placental serotonin systems in pregnancy metabolic complications associated with maternal obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus. BBA – Molecular Basis of Disease, 1866(2), N.PAG. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.01.017

Parker, H. W., Tovar, A., McCurdy, K., & Vadiveloo, M. (2019). Associations between pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and prenatal diet quality in a national sample. PLoS ONE, 14(10), 1–18. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1371/journal.pone.0224034

Simon, A., Pratt, M., Hutton, B., Skidmore, B., Fakhraei, R., Rybak, N., Corsi, D. J., Walker, M., Velez, M. P., Smith, G. N., & Gaudet, L. M. (2020). Guidelines for the management of pregnant women with obesity: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 21(3), N.PAG. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1111/obr.12972

Slack, E., Best, K. E., Rankin, J., & Heslehurst, N. (2019). Maternal obesity classes, preterm and post-term birth: A retrospective analysis of 479,864 births in England. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, 19(1), N.PAG. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1186/s12884-019-2585-z

Wang, X., Martinez, M. P., Chow, T., & Xiang, A. H. (2020). BMI growth trajectory from ages 2 to 6 years and its association with maternal obesity, diabetes during pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and breastfeeding. Pediatric Obesity, 15(2), N.PAG. https://doi-org.libproxy.clemson.edu/10.1111/ijpo.12579

a measure of body fat that is the ratio of the weight of the body in kilograms to the square of its height in meters

A form of diabetes mellitus that develops or is first recognized during pregnancy and, if untreated, can lead to complications such as preeclampsia and high birth weight. It is associated with an increased risk of subsequent development of type 2 diabetes.

https://www.yourdictionary.com/gestational-diabetes#americanheritage

a product of living cells that circulates in body fluids (such as blood) or sap and produces a specific often stimulatory effect on the activity of cells usually remote from its point of origin

the vascular organ in humans that unites the fetus to the maternal uterus and mediates its metabolic exchanges through a more or less intimate association of uterine mucosal with tissues

a condition (such as autism or dyslexia) that is typically marked by delayed development or impaired function especially in learning, language, communication, cognition, behavior, socialization, or mobility : DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITY

of or relating to fat

a class of animal or vegetable fats, especially plant oils, whose molecules consist of carbon chains with many double bonds unsaturated by hydrogen atoms and that are associated with a low cholesterol content of the blood.

https://www.dictionary.com/browse/polyunsaturated