17

Maclaine Hanvey

The importance of school meals

Obesity rates in the United States have grown rapidly in recent years and childhood obesity is at an all-time high. Children are often dependent on their parents or guardians for their meals, but children also spend a majority of their day at school. This means that their meals and habits at school have a major impact on their nutrition. School systems within the United States have implemented different types of nutrition programs, which are set up by government agencies, to help combat the rising rates of childhood obesity and create healthier habits in American children.

The National School Lunch Program

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) oversees almost all things food-related in the United States and this includes school nutrition programs. They established one of the largest programs known as the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). This was signed in 1946 under the Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act and, as of 2016, provides nutritional lunches to over 30.4 million students each day (United States Department of Agriculture, 2017). The goal of this program is to provide set nutritional standards for school breakfast and lunch at little to no cost for the student who qualifies while also reducing food insecurity in these same students. The USDA set a series of strict guidelines that require a variety of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains making these meals more nutrient-dense. This means that these foods have higher nutrient levels while having fewer calories. They also limited the amount of sodium and saturated fat within each meal (Center for Disease Control, 2019).

The School Breakfast Program

In addition to the NSLP, the USDA also established the School Breakfast Program (SBP). The SBP was put into effect in 1966 and as of 2016, almost 15 million children were receiving nutritional breakfasts during school (USDA, 2017). This program, like the NSLP, was set up to provide nutritional meals to students of all ages who attend either public or non-profit private schools. The main goal was to promote a healthier learning environment and lifestyle among American students.

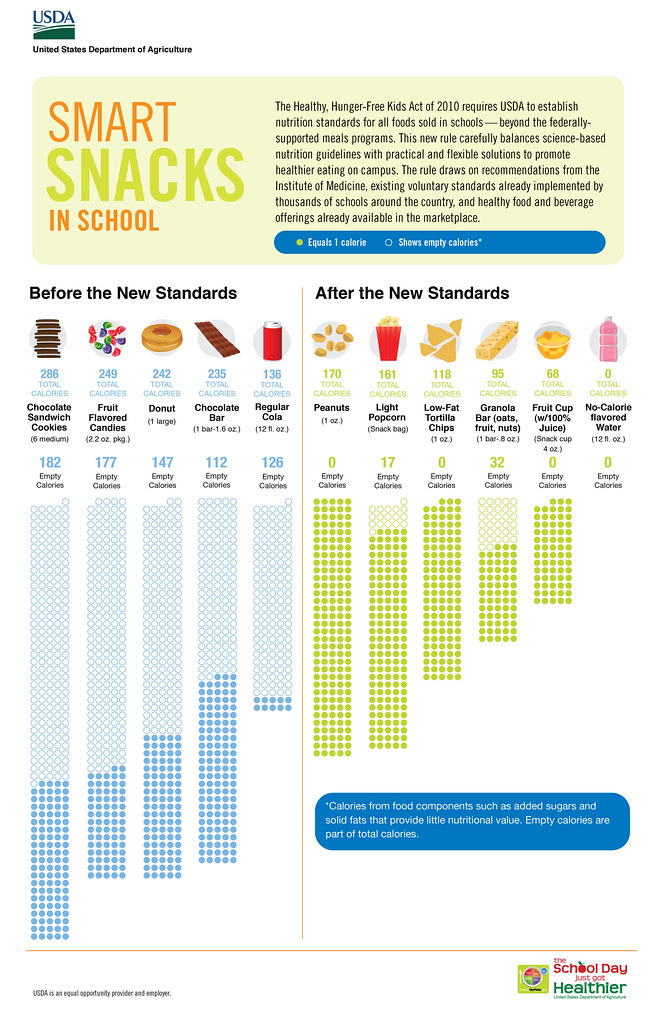

The Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model

Another way that schools have focused on nutrition is by using the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model (WSCC). This model was developed by the Center for Disease (2019). It focuses on ten different areas within the school system, including nutrition, to promote a healthier environment for students in the United States (CDC, 2019). One of the main goals of this model was to give students access to healthier foods and beverages through more nutritious school meals and snacks while at school while addressing student health (CDC, 2019). This model is used by many schools throughout the country and follows USDA nutritional guidelines.

Benefits of school nutrition programs

Each of these programs has specific benefits (School Meal Program Fast Facts). According to research, the NSLP and SBP together have led to lower rates of food insecurity in school children. They have also led to increases in fruit and vegetable consumption among students (Robinson-O’Brien & Burgess-Champoux, 2010). Another study found that students who participated in the NSLP and SBP programs, and other similar programs, also had a better diet outside of school and saw academic improvements compared to students who were not involved in these programs (Ralston et al., 2017). Researchers also found that students who participated in programs, and models similar to those listed above, saw a lower body mass index (BMI) compared to students who were not involved in nutrition programs (Yip et al, 2016).

The cost of school nutrition programs

One of the main downfalls is that these programs cost a lot of money to implement. Districts that implement the NSLP and the SBP receive reimbursements from the federal government based on whether or not the children receive a free meal, a reduced-price meal, or a paid meal (USDA, 2017). The United States Department of Agriculture (2017) specifies that school districts cannot charge more than 30 cents for a reduced-price breakfast and 40 cents for a reduced-price lunch. The rest of the cost of the meal comes from the district’s budget. These payments take time to process and the reports required for the reimbursement can be lengthy. School districts eventually receive reimbursements but only after the report is filed. Another downside to these programs is that they only occur during the school year, leaving many children reliant on their parents to provide meals while they are not in school. There are certain programs, like local meal backpack programs, that are put on in some school districts to provide food for children living in food-insecure areas but these are only present as long as there is enough food. Many of these programs rely on donations to local food banks and food drives.

Moving forward

All of the benefits and downsides listed above are extremely important for districts to consider but one of the most positive aspects of these programs and models is that they can be implemented nationally. Administrators and legislators are more likely to support these efforts and research shows that programs with more support are more successful overall (Robinson-O’Brien & Burgess-Champoux, 2010).

Moving forward, the public must fight for these programs in every school district across the country. These programs are backed by research and are proven to benefit the students who rely on it for nutritious meals. Parents and the local community should also push for schools to adopt the WSCC model, alongside the NSLP and the SBP to create a healthier learning environment for all children. Another goal moving forward should be to focus on implementing programs throughout the entire year and not just while school is in session. People can get involved in local backpack programs to help make sure students are receiving healthy food all year long. This would continue to benefit children and would help lower BMIs and improve student’s academic performance while promoting healthy habits.

Summary

School nutrition programs are a necessity for food-insecure students (see infographic below). The National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program are two federally-funded programs that aim to provide healthy meals to students throughout the school day. Other models like the Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child Model from the Center for Disease Control aim to promote healthy choices in all areas of the school system. These programs and models can be implemented to help promote healthy food choices in students and reduce food insecurity.

Review Questions

1. School districts receive reimbursements from the federal government based on ___?

a. The size of the school

b. The number of free and reduced meals distributed

c. The student’s attendance rate

d. The total number of students that use the nutrition programs

2. Students attending which school, if any, would not qualify for the NSLP or the SBP?

a. Low-income public schools

b. Non-profit private schools

c. For-profit private schools

d. All would qualify

3. What is the most that a district can charge for a reduced-price lunch?

a. 25 cents

b. 30 cents

c. 40 cents

d. 50 cents

References

Center for Disease Control. (2019). Comprehensive Framework for Addressing the School Nutrition Environment and Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/nutrition/pdf/School_Nutrition_Framework_508tagged.pdf

Ralston, K., Treen, K., Coleman-Jensen, A., & Guthrie, J. (2017). Children’s Food Security and USDA Child Nutrition Programs. AgEcon Search. http://dx.doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.259730

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2019, October 29). Student Meals Helps Millions of Children Grow up Healthy. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/infographics/school-meals-help-millions-of-kids-grow-up-healthy.html

Robinson-O’Brien, R. & Burgess-Champoux, T. (2010). Associations Between School Meals Offered Through the National School Lunch Program and the School Breakfast Program and Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Ethnically Diverse, Low‐Income Children. Journal of School Health. 80(10). 487-492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00532.x

United States Department of Agriculture. (2017, November). The National School Lunch Program. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/NSLPFactSheet.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture. (2017, November). The School Breakfast Program. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/SBPfactsheet.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture. (2013, June 26). Smart snacks in school [Infographic]. 9143713859.

Yip, C., Gates, M., Gates, A., & Hanning, R. (2016). Peer-led nutrition education programs for school-aged youth: a systematic review of the literature. Health Education Research. 31(1). 82-97. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyv063

unable to consistently access or afford adequate food

a measure of body fat that is the ratio of the weight of the body in kilograms to the square of its height in meters