1

Anna Kelly, Duncan D’Olimpio, Gavin Scannapieco, and Giovanni Ramirez

Abstract

This chapter will discuss the question “How can Brazil keep a healthy economy while still protecting the Amazon?” South America’s agriculture boom has led to the expansion of the cattle industry in Brazil. This requires the deforestation of the Amazon in order to increase pasture land. The Amazon, referred to as the lungs of the world, produces 20% of global oxygen and boasts 2.5 million species. The chapter will discuss deforestation in Brazil and the threats to biodiversity that it poses. This chapter will explore these topics through expert interviews and research.

Background of the Problem

A growing global demand for meat has changed the agriculture industry to increase its soy harvest to fatten and feed the new livestock (Marcio da Silva). One of the areas greatly impacted by the increase in agriculture is South America, specifically Brazil, home to the Amazon Rainforest (Pereira et al., 2012). In the past 50 years, roughly 17% of the Amazon has been destroyed (Nunez, 2019). The Amazon is referred to as the lungs of the world (Francombe, 2019; Woodward, 2019). A large portion of the Amazon is rainforest, and rainforests yield some of the highest rainfall per year in meters. It holds a huge carbon deposit and contains 20% of the world’s freshwater (Brazil and the Amazon). The Amazon is not just a rainforest, even though that is the most biodiverse and largest part of it (Rogers, 2020). There are also the Savanna and the Cerrado. This is the site of the biggest agricultural transformation Brazil has seen in many years (Rogers, 2020).

The Amazon is also home to one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world (Thomson, 2020). Protecting and conserving the Amazon not only saves countless species of known and unknown organisms but is also a fighter against climate change (The World Bank, 2019). The Amazon holds nearly 2 billion tons of carbon (Eaton, 2018), and with a potential die out in the forest, much of that carbon would be released into the atmosphere (Marshall, 2020).

This pristine land is facing a major crisis of deforestation largely because of the growing demand for certain crops and pasture land for cattle (Prager, 2019). The land being used for cattle is four times the amount of land being used for crops, even though cattle have a very low yield—sometimes just one cattle per hectare (Yale, 2020). The process of turning land from forest into cropland relies on the slash and burn method, a method that last year started 40,000 fires (Hauser, 2019) in the rainforest and led to the destruction of thousands of acres of forest. Slash and burn is a method of igniting a forest or brush until it has burnt to the point of complete ash (Lindsey, 2004). The rate of deforestation in the Amazon has been increasing, as July of 2019 saw a 39% increase compared to the rate of deforestation in July 2018 (Woodward, 2019).

The free-range cattle industry, which relies on grazing to feed the animals, also relies on the practice of slash and burn deforestation to clear new land for grazing (Lindsey, 2004). Recently under the new administration in Brazil, fires have been increasing in numbers as well as in size and unpredictability (Woodward, 2019). With many of these fires getting out of control to the point where they cause serious damage (Woodward, 2019), we need to address these issues in a proper and realistic manner to conserve this important environment. How can Brazil create a healthy economy while still protecting the Amazon? What can other nations do to support the protection of the Amazon and slow deforestation? With these leading research questions, we will be investigating a resolution that can work for both the farmers and the Amazon.

Why Should We Care?

This project holds an answer to a pressing problem that has recently been ignored and will inevitably impact every member of this planet if not dealt with. We are at a historical moment where the health of the entire Amazon is dependent on what the next couple of decades hold. Our research can be used by other nations to see how they can support the Amazon instead of supporting its deforestation. Our hope is that with our research and our conclusion, practitioners of forest management will have a better idea of what the guidelines should be for logging and clearing land for farming purposes. Our research can also be used by livestock economics to see how to better use the land. Land can be used in a more sustainable way in order to stop the need for expansion of said land. Our conclusion should also help with environmental conservation because, if put in place, the steps we outline and recommend should lead to a decrease in the deforestation of the Amazon, leading to the decrease in loss of biodiversity.

How Did We Collect Our Information?

In order to approach this problem, our team read many articles about the Brazilian economy and why the Amazon is being deforested. These articles have been discussed throughout the chapter and are linked here for those who want to read more in-depth. In our search to fully understand this project, we also conducted interviews. We interviewed four people: Dr. Charles A. Hall, Kathy Wolf, Dr. Claiton Marcio da Silva, and Professor Thomas Rogers. Dr. Hall, a systems ecologist, discussed during our interview the Law of Conservation of Evil. This is the theory that as one problem is fixed, another arises in its place. This is important in our project because we need to make sure that as we try to stop the deforestation of the Amazon and the loss of biodiversity, we are not ruining Brazil’s economy and people’s source of food.

Kathy Wolf, a research social scientist with ties to the USDA Forest Service and the University of Washington, discussed during our interview how there can be a better spatial efficiency of people. We can use what we have a lot better than how we are currently. One way this is being done is by Biophilic City Networks. This is an initiative to use nature and its resources more efficiently and effectively. Many cities are innovating by redesigning land to have multiple purposes. This relates to our project because if we can use our land more effectively and with multiple purposes, then we do not need to use as much land and the Amazon can stop being deforested.

Dr. Marcio da Silva, a professor at the Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul (UFFS) in Santa Catarina, Brazil, gave us a lot of background on the problem. He talked a lot about the soy industry. He told us that most domesticated animals are fed by soybeans and Brazil is one of the largest producers of soybeans in the world. He also mentioned that every year about 73% of Brazilian soybeans are exported to China, which means that stopping deforestation of the Amazon could lead to a major decline in Brazil’s economy. This is something that is a major factor when determining solutions and recommendations for this problem.

Thomas Rogers, a professor in labor and environmental history focusing on Brazil, discussed mainly what various steps can be taken when trying to stop the deforestation of the Amazon. His remarks can be found in the Recommendations section.

Our Findings

Through this investigation, we have uncovered a significant amount of information surrounding our research questions. It was unfortunate to uncover how little power one person has on this issue or even 10,000 people do, as this problem is controlled by a few powerful people in only a few countries. Another significant note is how severe this problem can become if nothing is done in the next couple of decades. The Amazon is an ecosystem like any other that requires a certain amount of vegetation to create its water supply that leads to its rainforest qualifying precipitation. Many reports indicate that 15-17%of the Amazon has already been lost, and if more than 25% of the Amazon is lost a severe irreversible problem will arise (Irfan, 2019); there will not be enough vegetation to cycle the water supply (Irfan, 2019). The eventual demise of the Amazon will not lead to a massive plot of soy farms, but a savannah.

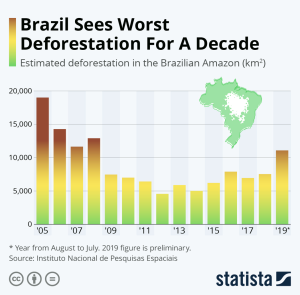

Through our research, we were able to compare different administrations and their impact on the environment. Generally, presidents before 2003 did not care about the environment to an effect that there were any significant decreases in deforestation rates. Then things began to change under the administration of Luiz Inácio Lula de Silva. Lula de Silva was able to lobby for more land to be considered protected and gave more to indigenous tribes. Though Lula de Silva’s presidency came to an end in 2011, his outlook on the environment continued under the administrations of Dilma Rousseff, his successor. Things began to degrade from there as more conservative, agriculturally minded congressmen were elected leading to the current President, Jair Bolsonaro. Under Jair Bolsonaro, in 2020 Brazil had seen its worst year of deforestation in a decade.

Through our interviews, we were able to collect a lot of information that would lead to us understanding this problem more and finding realistic solutions to this problem. To understand the problem, Professor Rogers and Dr. Marcio da Silva helped a lot. Professor Rogers talked about how small-hold farmers are getting blamed for a lot of the deforestation when in reality, it is the farmers with a greater wealth that are doing this. There are a lot of small-hold farmers deforesting the Amazon, so many people think that they are the cause. If we look at the acreage of their deforestation, we see it is a lot less than more established farmers. Another thing we learned from our interview is that the soil in the Cerrado is not good for growing crops, so in 1973 there was a mandate to make the Cerrado bloom (The Economist, 2013). This worked very well and soil amendments were found in order to enrich the soil and make it amenable to cropping. This happened at the same time Asia had a rise in food needs and was looking for “high quality, protein rich animal feed” (Rogers, 2020). They were looking for soy, and Brazil quickly became one of the largest soy exporters in the world behind the US. In 2019, they took over the role of the largest soy exporter in the world because of Trump’s trade war with China.

In 2006, there was a soy moratorium signed by all of the biggest producers of the world producing out of the Amazon. This moratorium basically said that they will not produce out of the Amazon, and it worked. The deforestation of the Amazon decreased steadily over the early 2000s. Unfortunately, the rates came back up. Just last week the reports for this past year said that 10,000 kilometers squared were deforested, which is 34.4% higher than last year (Butler, 2019). It is said that most of the deforestation is caused by illegal burning, and in 2018, 90% of the fires were illegal (Rogers, 2020).

Dr. Marcio da Silva touched upon what needs to be done in Brazil in order for anything to change. He said that the European Union is important, and it is important that they put some pressure on the Brazilian government to decrease deforestation. He continued to say that though the EU is important, nothing will change much unless China also puts pressure on Brazil, because 73% of Brazilian soy export goes to China. Unfortunately, at this moment China is not doing anything (Marcio da Silva, 2020). He also told us that the main change will not come from social pressure on the Brazilian government, but rather from work pressure. Brazil wants to protect its economy and the livelihoods of its workers, so unless a majority of their workers demand change or China does, our recommendations in the following part will only be steps to helping the problem, not the full solution.

The main conclusion of our research is that something needs to change now. The Amazon needs to start being protected more now. If we wait too long it will be too late. Though this sounds intimidating, it is not. The next section will talk about our recommendations for this problem. If these recommendations are followed, along with what we believe still needs to be done, it is realistic to assume that the Amazon can be saved. For the general public reading this, it may seem like a big problem that you alone cannot fix. That is true, but you are not alone. Many people are trying to save the Amazon. The French government, along with Ireland and others, are trying to save the Amazon (Corbet & Leicester, 2019). This may seem like a big undertaking, but our conclusion is not that one person can save the Amazon. Many people need to take action. There are already a lot of people, but more people discussing this issue will only help to get it resolved faster.

What Now? Our Recommendations

Although this is a huge issue, it can be solved. In 2006 there was a soy moratorium that was signed by all of the biggest producers of soy saying that they will not produce out of the Amazon. This worked very well and deforestation decreased at pace. That stopped when Jair Bolsonaro became president. He is, unfortunately, not a friend of the environment, so when the 2002-2016 worker power got cut, so did the IBAMA budget. Though this is unfortunate, it shows what the solution to stop deforestation could be.

When trying to find solutions, we reviewed our interviews. The interview with Dr. Hall was very important because it made us think about the implications of our proposed recommendations. We considered the Law of conservation of evil in all of our recommendations and believe that our recommendations will not cause any harm. The interview with Professor Rogers was particularly helpful. He advised us to look at what has already been done and has worked. This is when we looked at previous environmentally friendly governments in Brazil and how they drove down deforestation rates drastically. So what were they doing differently? That’s a simple answer: they were giving funding to various companies and empowering the agencies that were dealing with the Amazon (Rogers, 2020). He told us about all the wonderful laws that Brazil has in place that unfortunately are not enforced. So now that we know this, what is a solution we should propose? With the help of Professor Rogers, we decided that political will needs to be generated to enforce the laws on the books. We know this is realistic because it happened in 2017 (Lorenzon, 2017). As Professor Rogers put it, “We need to do more than just what the British see.” Now is the time for the world to come together as a union to protect this special ecosystem of the Amazon before it is too late. Many people seem to think this is not an issue right now, that we can come back in the future and worry about it then, but that is simply not the case.

One recommendation is instead of boycotting agencies involved with deforestation, we pay them not to harm the Amazon. This is something that an outside power can do. Agencies would be more open to this idea than having groups lobbying against them (Rogers, 2020).

Another recommendation for an outside power would be to partner with Brazilian companies. In the past, Brazil has not taken too kindly to foreigners coming in because they do not understand how closely linked the Amazon is to Brazil and Brazilian culture. By partnering with Brazilian companies, such as environmental NGOs, the people of Brazil would be more open to the ideas suggested by the people that live there and understand their culture and way of life. This would also allow new ideas to come in from outside powers without it seeming like they are trying to change Brazilian culture. In the 1992 Earth Summit held in Rio, environmental groups in Brazil got a big boost. The groups developed more and proposed laws. Brazil has a lot of really great laws, but they are not enforced. This leads to our third recommendation.

We recommend that companies involved with Brazilian companies try to get those companies to generate the political will to enforce the laws Brazil already has. These laws have already been passed by legislature and just need to be enforced. A 2012 forest code protected 80% of the Amazon from being deforested. When it was revisited, it was revised to give landowners more power over their land. Though they allowed increasing how much of their property they could deforest, it was still a small enough amount that would save the majority of the Amazon. If that law is enforced, then already a large amount of the Amazon is protected.

Our fourth recommendation is something that will be hard to change, but if it is done, it will be very positive. The various trends in food change frequently and rapidly. Due to this, changing food habits should not be the sole thing being done in order to protect the Amazon, rather one of a few things. Brazilian beef consumption has increased to 5 times as much as the start of the 20th century. One reason for this increase is aspirational eating. This is when people mimic the eating patterns of what has been shown in commercials. If eating more plant-based diets becomes popular in commercials, then the public will be more likely to change their diet. This will lead to less need for pasture land for cows and the land that they have for other products should be enough. This is a recommendation for the general public: change your diet. We are not saying boycott meat from Brazil. We are saying to try to eat less meat. One of Brazil’s most important exports is soy. By reducing the general public intake of meat, it will not bankrupt the Brazilian economy. Brazil exports a lot of soy to feed China’s animals, but animals produce more than just meat. Reducing how much meat you eat will not make China stop feeding their animals and needing a lot of soy to do that.

All of our recommendations are things we believe are practical and will help the Amazon. That does not mean that the problem is solved once these steps go into place. There are other things that need to be done. One of those things is more research on co-beneficial land, as talked about by Kathy Wolf. This is something that will maximize what the land has to give. She told us that we can use what we have so much better in terms of efficiency. We also believe that there should be more research on sustainability and more steps taken to achieve that. Finally, one last thing that, at this time, our group believes still needs to be done is for the Brazilian workforce to care. They are worried about their livelihood, which is understandable, but with reasonable change, they can keep their livelihood and save the Amazon.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we believe that things need to change now. As already stated, 15-17% of the Amazon has already been lost and we cannot let it get to 25% (Irfan, 2019). The current administration in Brazil is contributing to this problem, but they have shown little effort to prevent the fires or deforestation in the Amazon. The next Brazilian president needs to care about the environment and be more like Lula da Silva, someone who cares about the land and its protection. Although it is good to have some agriculturally-minded congressmen in the government, we also need environmentally-minded congressmen who have more of a say. The Amazon does not just impact Brazil, it impacts the world. Likewise, the destruction of the Amazon will not just impact Brazil, it will impact the world.

Our research proves that this issue is not only ecological and economic but also social and political. The social aspect is the culture of Brazilian people. The indigenous tribes that Lula da Silva gave more of the Amazonian land to identify the Amazon as part of their culture. Another social aspect is something that can also be considered political. Brazil is not inclined to let foreign governments or companies come to Brazil and demand things. In order to get things accomplished, there needs to be a balance between foreign governments and companies demanding things and respecting the Brazilian people. If Brazilian companies are the ones to demand changes and are backed by foreign companies, things are more likely to change. Another political aspect is that there are environmentalists in Brazil, but as Dr. Marcio da Silva stated, “Brazil’s right-wing and left-wing are committed to development to increase exportation and to increase money to build infrastructure.” (Marcio da Silva, 2020).

Through this study, we were able to investigate the agricultural impacts on the Brazilian environment and just what exactly is at risk. The ecosystem surrounding the Amazon river is biodiverse like no other corner of the globe with 2.5 million species, some at risk of extinction now and many more in the inevitable future. As a species of this planet that has benefited from the Amazon’s medicinal and carbon controlling components, we have an ethical responsibility to protect and converse this ecosystem. This research and proposed solutions will benefit society because they will help save our planet. Otherwise, 2.5 million species will lose their homes, and many of them will go extinct. We will lose one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world (Thomson, 2020). We will also lose 20% of the world’s freshwater (Brazil and the Amazon). One of the most concerning things that could happen though is the 2 billion tons of carbon that the Amazon holds (Eaton, 2018), which could be released into the atmosphere (Marshall, 2020).

We believe that there are other situations when a similar solution may be helpful. There are a lot of other forests being deforested, not just the Amazon. The Amazon is what we decided to focus on for this project, but with some tweaking of our recommendations, they can be beneficial for other forests. Something that we believe others can learn from our project is that we need to think outside of the box sometimes. Who would think that in order to solve a problem, we should backtrack and do what those in the past did? That is what needs to be done in this case, though. Another thing we think people can learn from our project is that a big problem requires a big effort to solve. Time and research need to go into understanding the problem. Then the problem needs to be analyzed, and then it can be solved. The solution will not be only one step, rather it will be multifaceted. It will not be able to be fixed in a matter of days or weeks or even months. It may take years, but if energy is put into understanding the problem and analyzing it, the solution will show it. We also want to remind people that some steps of the solution may not work or may need to be revised. Most solutions are not 100% accurate to start. It takes time to perfect them, but if you put in that time, they will work.

Acknowledgments

We wanted to acknowledge and thank Dr. Charles Hall, Kathy Wolf, Dr. Claiton Marcio da Silva, and Professor Thomas Rogers for taking the time to talk to us. Without these interviews, our chapter would not be what it is. We also want to thank Professor William San Martin, Professor Marja Bakermans, and our PLA Blaise Pingree.

Additional Resources

We would like to recommend for more information, the reading of an article called “The Root of the Problem: What’s Driving Tropical Deforestation Today?” This was a very helpful article for us when writing this chapter and provides a very detailed account of what is happening in the Amazon. The link to the article is here. We would also like to recommend that this video be watched. It is a video detailing what is happening in the Amazon. It presents the information of the causes of deforestation and their effects in a clear way. We recommend visiting both of these sites because they complement each other well.

References

Andreoni, M., & Hauser, C. (2019, August 21). Fires in Amazon rain forest have surged this year. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/21/world/americas/amazon-rainforest.html

Aragão, L. E. O. C., Anderson, L. O., Fonseca, M. G., Rosan, T. M., Vedovato, L. B., Wagner, F. H., Silva, C. V. J., Silva Junior, C. H. L., Arai, E., Aguiar, A. P., Barlow, J., Berenguer, E., Deeter, M. N., Domingues, L. G., Gatti, L., Gloor, M., Malhi, Y., Marengo, J. A., Miller, J. B., … Saatchi, S. (2018). 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nature Communications, 9(1), 536–536. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02771-y

Butler, R. (2019). Ecology of the Amazon rainforest. Mongabay. https://rainforests.mongabay.com/amazon/rainforest_ecology.html

Cilluffo, A., & Ruiz, N. G. (2019, June 17). World’s population is projected to nearly stop growing by the end of the century. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019 /06/17/ worlds-population-is-projected-to-nearly-stop-growing-by-the-end-of-the-century/

Corbet, S., & Leicester, J. (2019, August 23). France threatens economic retaliation over Amazon fires. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/df4d58900129449796c8c51e4a706d2e

Eaton, S. (2018, October 2). The Amazon used to be a hedge against climate change. Those days may be over. Livable Planet. https://interactive.pri.org/2018/10/amazon-carbon/science.html

Francombe, A. (2019, August 23). Why do people call the Amazon rainforest the “lungs of the earth”?. The Face. https://theface.com/society/amazon-rainforest-emmanuel-macron-angela-merkel-environment-climate-change

Fujisaka, S., Bell, W., Thomas, N., Hurtado, L., & Crawford, E. (1996). Slash-and-burn agriculture, conversion to pasture, and deforestation in two Brazilian Amazon colonies. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 59(1–2), 115-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8809(96)01015-8

Hall, C. (2020, November). Personal communication [Personal interview].

Irfan, U. (2019, November 18). Brazil’s Amazon rainforest destruction is at its highest rate in more than a decade. Vox. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2019/11/18/20970604/amazon-rainforest-2019-brazil-burning-deforestation-bolsonaro

Lindsey, R. (2004, June 8). From forest to field: How fire is transforming the Amazon. NASA Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/AmazonFire

Lorenzon, G. (2017, November 20). Corruption and the rule of law: How Brazil strengthened its legal system. CATO Institute. https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/corruption-rule-law-how-brazil-strengthened-its-legal-system

Marcio da Silva, C. (2020, November). Personal communication [Personal interview].

Marshall, M. (2020, May 26). Planting trees doesn’t always help with climate change. BBC Future. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200521-planting-trees-doesnt-always-help-with-climate-change

Nunez, C. (2019, May 15). Rainforests, explained. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rain-forests/

Pereira, P., Martha Jr. G., Santana, C., & Alves, E. (2012) .The development of Brazilian agriculture: future technological challenges and opportunities. BMC Agriculture and Food Security. https://doi.org/10.1186/2048-7010-1-4

Prager, A. (2019, March 19). Brazil’s key deforestation drivers: Pasture, cropland, land speculation. Mongabay News and Inspiration From Nature’s Frontline. https://news.mongabay.com/2019 /03/brazils-key-deforestation-drivers-pasture-cropland-land-speculation/

Rogers, T. (2020, November). Personal communication [Personal interview].

Vander Velde, B. (2019, September 23). France backs bold new pact to save Amazon. Conservation International. https://www.conservation.org/blog/france-backs-bold-new-pact-to-save-amazon#:~:text=A%20groundbreaking%20effort%20to%20protect,an%20additional%20US%24%2020%20million.

Wolf, K. (2020, November). Personal communication [Personal interview].

Woodward, A. (2019, August 22). The Amazon is burning at a record rate, and the devastation can be seen from space. Science alert. https://www.sciencealert.com/the-amazon-is-burning-at-a-record-rate-and-parts-were-intentionally-set-alight

(2013, September 26). Leave well alone. Brazil’s agriculture has benefited from government neglect. Its car industry has had too much attention. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/special-report/2013/09/26/leave-well-alone

(2019, August 23). Amazon fires: Brazil threatened over EU trade deal. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-49450495

(2019, May 22). Why the Amazon’s biodiversity is critical for the globe: An interview with Thomas Lovejoy. The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/05/22/why-the-amazons-biodiversity-is-critical-for-the-globe

(2020). Cattle Ranching in the Amazon Region. Yale School of the Environment, Global Forest Atlas. https://globalforestatlas.yale.edu/amazon/land-use/cattle-ranching

The action of clearing a wide area of trees.

The variety of life in the world or in a particular habitat or ecosystem.

The Cerrado is a vast tropical savanna ecoregion of Brazil, The core areas of the Cerrado biome are the Brazilian highlands, the Planalto. The main habitat types of the Cerrado consist of forest savanna, wooded savanna, park savanna and gramineous-woody savanna. Savanna wetlands and gallery forests are also included. The second largest of Brazil's major habitat types, after the Amazonian rainforest, the Cerrado accounts for a full 21 percent of the country's land area (extending marginally into Paraguay and Bolivia).

A metric unit of square measure, equal to 100 ares (2.471 acres or 10,000 square meters).

A method of igniting a forest or brush until it has burnt to the point of complete ash

1. The science in which the principles and methods of economics are applied to the special of livestock industry.

2. Refers to production plan and production of livestock product and by product, management of livestock farms, utilization of resources uses and finally marketing of livestock product and by product from the producing point to ultimate users point with the mind of maximum benefit and minimum costs.

Able to be maintained at a certain rate or level.

A grassy plain in tropical and subtropical regions, with few trees.

a temporary suspension of an activity or law

This is the theory that as one problem is fixed, another arises in its place

A nonprofit organization that operates independently of any government, typically one whose purpose is to address a social or political issue.