9

Jennifer Brownell, Vivek Kandasamy, Peter Lam, Julia Naras, and Olivia Petropulos

Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua)

An Introduction

Cod has been integral to North American history and cultures since long before the arrival of European settlers. Indigenous Peoples of the East and West coasts have angled, jigged, spearfished, netted, and trapped the abundant fish for tens of thousands of years. The fish was nutritionally and culturally important in areas where the land could not support agriculture and is still recognized in Indigenous oral traditions as a fountainhead of life (Chaves 2014).

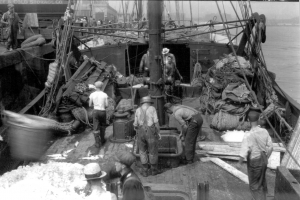

In New England, the commercial fishing of Atlantic cod became the first American industry and supported the growth of the Colonies (Chaves 2014). Fishing towns that still exist today—Provincetown, Gloucester, New Bedford, Nantucket, et cetera—thrived because of the healthy Atlantic cod fishery and guidance from Indigenous Peoples (Figure 2) (Dybas 2006). The fish was a symbol of New England’s economic prosperity and physically manifested in a five-foot-long Sacred Cod carved out of pine was hung in the Massachusetts State House. Three hundred and twenty years later, a replica still resides in the Massachusetts House of Representatives just west of Cape Cod Bay (Dietze 2017).

Now, however, this icon is fading away. As overexploited Atlantic cod stocks dwindle, New England fishing communities struggle with the loss of income (from commercial fishing and recreational guided fishing trips), food security, and regional culture. The ecosystems that once supported cod populations have changed irreversibly in their absence, and conservation efforts have had little to no success in recovering them.

Natural History and Significance

Atlantic cod is a species as unique physically as it is culturally. Both females and males have three spineless dorsal fins, two anal fins, and a single barbel on the chin. They can change color based on their depth in the water column, often appearing greyish-green or reddish-brown with a light belly. A pale lateral line runs from above each pectoral fin to the squared caudal fin (Figure 3) (NOAA 2020). Females grow slightly heavier and longer than males but otherwise, they are indistinguishable (Jakobsen et al 2016). According to current government sources, within their 20-year lifespan, they can reach up to 77 pounds and 51 inches long (NOAA 2020). However, 19th-century schooner records show that Atlantic cod once exceeded 210 pounds (Dybas 2006).

This species’ domain expands beyond New England’s watersheds but is limited to the Atlantic and the Arctic Oceans. To the west, they can be found from off the shores of Greenland, all the way to North Carolina. To the east, they can be found from the Arctic Ocean to the Bay of Biscay. This includes other bodies of water like the North Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Barents Sea, as well as a few more. They are found in Europe all the way east to Scandinavia because of their seasonal migrations (Figure 4) (Commonwealth of Massachusetts 2021).

A shoaling species, Atlantic cod finds itself in rocky habitats, as well as down in the ocean along the continental shelf. Cod tend to prefer colder temperatures and deep water during the day. On the other hand, they enjoy the warmer and shallower water at night (Neubauer et al. 2013). Factors such as temperature, depth, and salinity can affect “growth rate, age of maturity, migration patterns, and timing of spawning” (Brander 2018). They spawn near the ocean floor from winter to early spring, beginning at age 2 or 3. Females can lay anywhere from 3 million-9 million eggs. A study on commercial fishing of Atlantic cod found that “total egg abundance is significantly higher in years with more old and large individuals in the spawning stock” (Stige 2017). They reproduce through broadcast spawning: a type of sexual reproduction where females release eggs into the water column where they meet up with sperms. This helps protect the eggs from egg predators (Stige 2017).

Cod is a generalist species with an omnivorous and ontogenetic diet. As they develop from “codlings” to medium-sized cod, their diet shifts from pelagic invertebrates to benthic invertebrates, small fish, and crustaceans. In ecosystems where populations of large cod are stable, they are the dominant piscivore and consume more fish (including smaller cod and other gadoids), crustaceans, and mollusks as they grow. Cod are opportunistic hunters and prefer the most abundant prey (Link and Garrison 2002). As a result, the species plays multiple roles throughout the trophic levels.

As a prey species, Atlantic cod links aquatic animals such as shrimp, crustaceans, and capelin, along with marine mammals such as harp seals and grey seals. Many types of fish prey on the Atlantic cod. Young and smaller cod are hunted by larger cod and pollock fish. Larger adults are hunted by sharks, spiny dogfish, and marine mammals (Link et al. 2009). Removal of cod will cause “an increase or decrease in abundance to every other species in the ecosystem in an alternating pattern” (Steele 2016) (Figure 5). As studied, a decline of the cod population has had an inverse effect for shrimp, crab, and foraging fish populations. However, this has led to large decreases in zooplankton which would be feasted on greatly from a now-unchecked predator (Bundy et al. 2009). While Atlantic cod plays a more predatory role in an ecosystem than prey, many species do still feed on cod “preying on the cod’s early life stages (eggs, larvae or early juveniles) or by competing with those early life stages for food” (Link et al. 2009). Cod plays a vital role in the economy, but more so in the ecosystems that they reside in.

Stock Collapse

Over the past 150 years, the population of Atlantic cod experienced significant changes. Through the 19th and early 20th centuries, Atlantic cod was a staple for the fisheries in the Northern Atlantic Ocean. However, starting in the late 1950s, offshore bottom trawlers began to fish in deeper parts of the stock (Walter et al. 2005). This led to a dramatic increase in the number of fish landings. Since there was a decrease in the number of fish, especially the most mature fish with the highest rates of reproduction, the population was unable to replenish the stock. The mass number of fish caught from the 1950s onwards led to a decline in the biomass of the Atlantic cod (Figure 6). While overfishing played a large role, it is not the only reason for the collapse of the Atlantic cod population (Walter et al. 2005). Other reasons for the decline include pollution, climate change, and human activity, which all led Atlantic cod to be declared a vulnerable species by 1996. Today, they remain vulnerable to extinction with some populations now being labeled as endangered (Ono et al. 2019).

Management Policies

In response to the cod stock depletion and its staggering effect on the fishing industry, Congress passed the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSFCMA), the first and principal marine conservation law, in 1976. The legislation protected U.S. waters from foreign fishing vessels and established eight management councils, appointing them by region to the nation’s major marine fisheries (NOAA 2020). The New England Fishery Management Council accounts for both Atlantic cod stocks in U.S. waters: the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank. All eight U.S. Regional Fishery Management Councils collaborate with scientists and workers in the fishing industry as well as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to regulate commercial and recreational fishing, protect habitats, and develop new strategies to restore overfished species (NOAA 2020).

Nevertheless, overfishing persisted and cod was listed as a vulnerable species in 1996 (Wilmot 2005). Many amendments have been made to the MSFCMA to address this, most notably the Sustainable Fisheries Act (1996) and the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act (2006), which further limited fishing access to vital habitats and enforced stricter catch limits (NOAA 2020). In 1986, the New England Fishery Management Council developed the Northeast Multispecies Fishery Management Plan to restore cod (and 12 other groundfish species) stocks (NEFMC 2021). Amendments and adjustments have also been made to the Northeast Multispecies FMP (and several are currently in progress); however, regulations have not reversed the decline of cod populations (Hayden et al. 2015; NEFMC 2021). New research analysis suggests that overharvested cod shoals group together, joining the once-fragmented populations. These metapopulations are easy targets for trawlers, making the fish vulnerable to overharvesting even when strict, traditional fishing regulations (e.g. landing limits) are in place (Hayden et al. 2015). This information is beneficial as organizations like the New England Fishery Management council work to develop new regulations to recover Atlantic cod.

With this new legislation, local fishermen had interesting opinions. At first, fishermen viewed the new restrictions as another barrier they must face. The restrictions also took away revenue. As time passed, the locals became better educated on the problems associated with the Atlantic cod collapse. Fishermen now recognize the importance of the government’s efforts to intervene in the collapse of an iconic and ecologically essential species. Locals adhere to the new restrictions and hope that this change in behavior can recover the species. This is a great example of how powerful education is. Not only do the people in power need to be educated to make a change, but the general public does as well. This issue highlights the fact that education brings about the knowledge to advocate for change (Oceana 2018).

Recovery

Despite the action taken by Congress, there have been no substantial results to show that the Atlantic Cod population has recovered at all. These actions seem like they are making large strides, yet there is a lot more work to be done. Most importantly, there is no set recovery plan in place for this species. Even though this species started to collapse many years ago, a true plan has yet to be made. This is an alarming reality because as quickly as a population can disappear, restoring it is extremely challenging and time and resource-consuming. This means that there needs to be more actions taken and effort exerted by those who can bring change (Hutchings and Kuparinen 2020).

Firstly, there needs to be support from the community and local fishermen to have these changes make a difference. Some of these restrictions make it difficult for fishermen to keep the cod they catch, as there is a limit to what they can catch in a day. This results in a large amount of dead cod that has been caught and thrown overboard. In 2018, one study found that it was not uncommon for there to be over 3,000 pounds of cod throw out per trip. Without knowledge of the current population and management compliance, it is not possible to fully know how the population of cod is doing. This makes it nearly impossible for scientists and government officials to set forth rules and a specific course of action. To fix this issue, all groundfish trips in New England would need to be monitored. As of late, people are starting to recognize how important complete monitoring can be. In addition, locals must recognize how detrimental recreational fishing of Atlantic cod can be. Recreational fishing creates additional challenges in properly monitoring the species (Hutchings and Kuparinen 2020).

Secondly, refuges should be set up for the Atlantic cod to protect their important habitat. Protecting the fish’s habitat protects the fish. Actions like this would stop the fishing of cod in specific areas. One of the most important aspects of this effort is that it can protect young cod and highly productive females (Hutchings and Kuparinen 2020). This action poses a method to quickly increase populations in areas.

Another effort that could be made in the distant future is the creation of modified fishing gear to reduce the amount of cod caught by accident. It is very common for cod to be caught while other fish species are being targeted. The creation of new gear could minimize this issue. This would require help from scientists as well as major funding to make this gear commonplace (Hutchings and Kuparinen 2020).

Overall, we can see that Atlantic cod is a victim of human greed and lack of education. With the start of the Industrial Revolution came a wave of production, which also meant the consumption of resources faster than anyone could predict. Today, Atlantic cod habitat waters run 53 degrees Fahrenheit. As humans warm up the planet, so do the oceans. The Gulf of Maine “is one of the fastest-warming bodies of water on Earth” (Lawson 2019) and the Atlantic cod’s range grows smaller and smaller.

These warmer waters are a challenge and a result of negligent human behavior within the environment, which has stunted the growth of the Atlantic cod population along with many others like it. Acidity levels are rising along with the temperature. Studies have found “that increasing acidification makes cod embryos more sensitive to higher and lower temperatures, effectively narrowing the optimal temperature range for reproduction” (Berwyn 2018). Factors such as these limit cod spawning areas, inevitably slashing future cod populations and their re-build.

The current COVID-19 pandemic has only made it harder on the fishing industry and the groups associated with conservation efforts of the threatened fish species. Now more than ever, the fishing industry needs financial support from the government as well as support from the community. Something the community can do is continually advocate for advancing rebuilding plans, promote education to those around, and follow the rules already set in place to protect Atlantic cod.

Conclusion

Like all living entities, the Atlantic cod has a complex natural history. What’s remarkable about this fish, however, is how its natural history is interwoven with human history. For millennia, the species was so important to human survival that entire cultures and technologies were developed around it (Dexter and Speck 1948). Initially, cod was a nutritional staple to Indigenous Peoples in New England. Following European settlement, it then became valued for its economic significance within the Colonies. Now, cod is an internationally sought-after commodity, a direct result of commercial demand and the advancement of fishing technologies since the Industrial Revolution (Dybas 2006). Serial overharvesting, especially of large cod in indiscriminating trawls, inevitably led to the collapse of the fishery. Despite continued government intervention since the 1970s, cod stocks continue to fall, fishing towns continue to struggle, and the trophic levels that healthy cod populations once supported are damaged without them (Steele 2016). Conservation success stories for Atlantic cod are rare, and climate change is an added challenge to recovery efforts. Although minimal, the Gulf of Maine has seen improvement in the cod fishery, which is attributed to strict landing limits, but more importantly, to strict area limitations and habitat preservation (Alexander et al. 2009). If we protect the habitat, then we protect the Atlantic cod.

References

Alexander KE, Leavenworth WB, Cournanel J, Cooper AB, Claesson S, Brennan S, Smith G, Rains L, Magness K, Dunn R et al. 2009. Gulf of Maine cod in 1861: historical analysis of fisherylogbooks, with ecosystem implications. Fish and Fisheries 10(4): 428-449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2009.00334.x

Berwyn B. 2018 November 9. Warning for seafood lovers: Climate change crash these important fisheries. Inside Climate News. [Intenet] [cited 2021 March 8] Available from: https://insideclimatenews.org/news/29112018/atlantic-cod-climate-change-fish-population-crash-risk-arctic-food-web-impact-study/

Brander KM. 2018. Climate change not to blame for cod population decline. Nature Sustainability 1(6) : 262-264. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0081-5

Brander KM. 2007. The role of growth changes in the decline and recovery of North Atlantic Cod stocks since 1970. ICES Journal of Marine Science 64(2): 211-217. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsl021

Comeau P. 1998. New endangered species plan unveiled. Canadian Geographic. [Internet] Available from: http://www.ucs.mun.ca/~kbell/cod/PRESS-sa_crspdnc/CG9807-28-30/CG9807p28-30.html

Dexter RW, Speck FG. 1948. Utilization of marine life by the Wampanoag Indians of Massachusetts. Journal of the Washington Academy of Science 38(8): 257-265. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24530881

Dietze MC. 2017. Case study: Natural resources. In: M Dietze, editor. Ecological Forecasting. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press. p. 131-137. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvc7796h.14

Drinkwater KF. 2005. The response of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) to future climate change. ICES Journal of Marine Science 62(7): 1327-1337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icesjms.2005.05.015

Dybas CL. 2006. Ode to a codfish. Bioscience 56(3): 184-191. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0184:OTAC]2.0.CO;2

Grafton RQ, Kompas T, Ha VP. 2009. Cod today and none tomorrow: the economic value of a marine reserve. Land Economics 85(3): 454-469. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.85.3.454

Hayden A, Acheson J, Kersula M, Wilson J. 2015. Spatial and temporal patterns in the cod fisheries of the North Atlantic. Conservation and Society 13(4): 414-425. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.179878

Hutchings JA. 2005. Life history consequences of overexploitation to population recovery in Northwest Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 62 (4): 824-832. https://doi.org/10.1139/f05-081

Hutchings JA, Kuparinen A. 2020. Implications of fisheries-induced evolution for population recovery: Refocusing the science and refining its communication. Fish and Fisheries 21(2): 453-464. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12424

Lawson G. 2019. Give Atlantic cod a break: The role of climate change. Conservation Law Foundation. Available from: https://www.clf.org/blog/give-atlantic-cod-a-break-climate-change/#:~:text=A%20warmer%20ocean%20also%20makes,and%20raise%20healthy%20young%20fish.&text=Scientists%20are%20working%20to%20understand,ocean%20is%20limiting%20population%20growth

Link JS, Bogstad B, Sparholt H, Lilly GR. 2009. Trophic role of Atlantic cod in the ecosystem. Fish and Fisheries 10(1): 58-87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2979.2008.00295.x

Link JS, Garrison LP. 2002. Trophic ecology of Atlantic cod Gadus morhua on the northeast US continental shelf. Marine Ecology Progress Series 227: 109-124. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps227109

Mason F. 2002. The Newfoundland cod stock collapse: a review and analysis of social factors. Electronic Green Journal 1(17). https://doi.org/10.5070/G311710480

Mirimin L, Desmet S, Romero DL, Fernandez SF, Miller DL, Mynott S, Brincau AG, Stefanni S, Berry A, Gaughan P, et al. 2021. Don’t catch me if you can – Using cabled observatories as multidisciplinary platforms for marine fish community monitoring: An in situ case study combining underwater video and environmental DNA data. The Science of the Total Environment 773: 145351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145351

Neubauer P, Jensen OP, Hutchings JA, Baum JK. 2013. Resilience and recovery of overexploited marine populations. Science 340(6130): 347-349. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230441

Neuenfeldt S, Bartolino V, Orio A, Andersen KH, Andersen NG, Niiranen S, Bergström U, Ustups D, Kulatska N, Casini M. 2020. Feeding and growth of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) in the eastern Baltic Sea under environmental change. ICES Journal of Marine Science 77(2): 624–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsz224

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), USDOC. 2019. Atlantic cod overview. [Intenet] Available from: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/atlantic-cod#overview.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), USDOC. 2020. Northeast multispecies (groundfish). [Internet] Available from: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/northeast-multispecies-groundfish#management.

Oceana. 2018. Fishermen explain: The Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) is vital. YouTube.com. [Internet] Available from: https://youtu.be/sfSnoxdFbOo.

Ono K, Knutsen H, Olsen EM, Ruus A, Hjermann DO, Stenseth, N. 2019. Possible adverse impact of contaminants on Atlantic cod population dynamics in coastal ecosystems. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 286(1908). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.1167

Powles H, Bradford MJ, Bradford RG, Doubleday WG, Innes S, and Levings CD. 2000. Assessing and protecting endangered marine species. ICES Journal of Marine Science 57(3): 669-676. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.2000.0711

Rose GA. 2004. Reconciling overfishing and climate change with stock dynamics of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) over 500 years. Canadian Journal of Fisheries Aquatic Sciences 61(9): 1553-1557. https://doi.org/10.1139/f04-173

Rose GA, Rowe S. 2015. Northern cod comeback. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 72(12): 1789-1798. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2015-0346

Schrank WE, Roy N. 2013. The Newfoundland fishery and economy twenty years after the northern cod moratorium. Marine Resource Economics 28(4): 397-413. https://doi.org/10.5950/0738-1360-28.4.397

Sellers AM. 2003. Environmental quality assessment of Georges Bank for Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). [thesis] Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Available from: https://web.wpi.edu/Pubs/ETD/Available/etd-0428103-155152/unrestricted/sellers.pdf

Sguotti C, Otto SA, Frelat R, Langbehn TJ, Ryberg MP, Lindegren M, Durant JM, Chr Stenseth N, Möllmann C. 2019. Catastrophic dynamics limit Atlantic cod recovery. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Biological Sciences 286(1898): 20182877. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2877

Trzcinski MK, Mohn R, Bowen WD. 2006. Continued decline of an Atlantic cod population: How important is gray seal predation? Ecological Applications 16(6): 2276–2292. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[2276:CDOAAC]2.0.CO;2

Angle is an archaic word for “hook”; angling is fishing with a rod, line, and hook

To fish with a rod, line, and a lure which is jerked through the water to attract fish

The fin located on the back of a fish

The fin located on the underside of a fish

A whisker-like organ used by bottom-feeding fish to search for food

The pair of fins on the left and right side of a fish behind the head

The tail fin of a fish

A ship with two or more masts

A group or school of fish

The reproductive process of most fish where eggs and sperm are released into the water

Consuming both plants and animals

Changing during an organism’s lifespan

An organism that consumes primarily fish

A fishing boat that carries a large net (a trawl)

The volume of organisms in an area

A listing of a species which is a higher species concern than "threatened" but not as serious as "endangered."

A large number of fish swimming together.

A collection of individual populations of the same species that interact with one another

A group of organisms within an ecosystem which occupy the same level in a food chain