4

Eric Adams, Nicholas Kenny, and William Miller

(An important factor to note is the lack of research conducted on this specific species due to the remote nature of the island they inhabit. Much information must be taken from its close relative, Bothrops jararaca.)

Natural History

Bothrops insularis, also known as the Golden Lancehead, is known to grow to an average length of 70cm and 90cm but can grow to around 118cm (Guimarães et al. 2014). As the common name implies, the Golden Lancehead is a pale yellowish-brown color and has a head common to the genus Bothrops that is triangular in shape (more like the head of a spear than a lance).

The diet of an adult B. insularis relies mainly on various bird species. Two species, in particular, Elaenia chilensis and Turdus flavipes, are some of the most abundant on the island. B. insularis is an opportunistic hunter, and with these two main bird species being migratory, they are not present on the island year-round (Marques et al. 2012). The diet of an infant B. insularis, on the other hand, relies mainly on ectothermic prey such as centipedes and frogs (Zelanis et al. 2007).

B. insularis is both terrestrial and arboreal, with the latter being mostly for hunting. As for shelter from storms or during digestion, the species is found to hide under leaves or rocks.

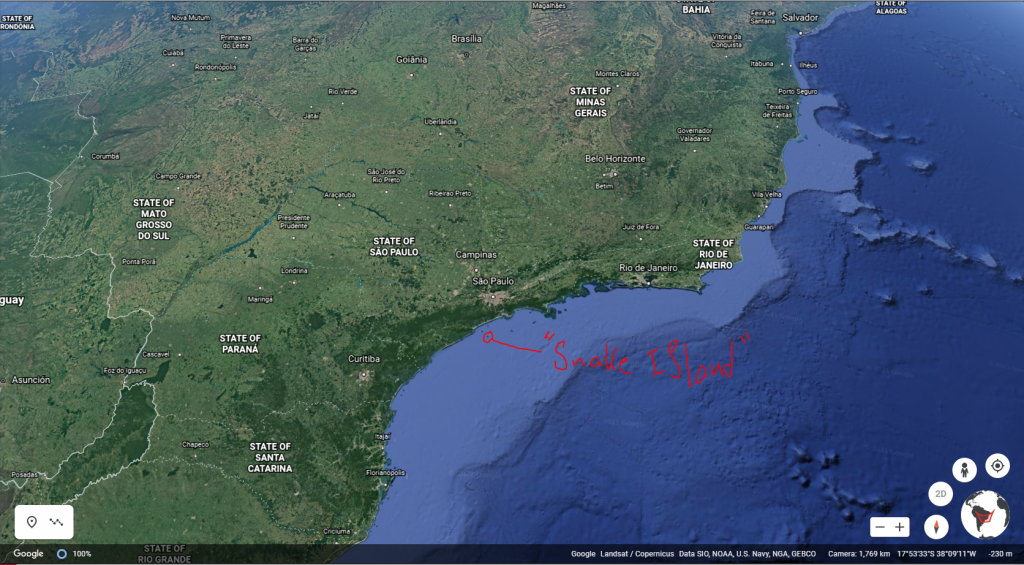

Range

B. insularis is native to Queimada Grande (Guimarães et al. 2014) island off the coast of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Known colloquially as “Snake Island”, the home of B. insularis is also home to a variety of other exotic and rare snake species and is the only place B. insularis has been found. The island is home to a few different biomes including rocky areas, small plains, and rainforests—which are the main habitat of the B. insularis. The Rainforests are in the lower regions of the island and cover about 60% of the island allowing for the snakes to have a relatively large range.

The B. insularis‘ close relative, B. jararaca, is endemic to southern Brazil, Paraguay, and northern Argentina. Due to this, it is expected that B. insularis could survive and grow in numbers should they be introduced to mainland South America.

Role in Ecosystem

The venom itself is some of the most powerful in the world. It not only has the effects of other powerful venoms like breaking apart red blood cells and causing hemorrhaging, but it is actually powerful enough to melt skin. The reason for such potent venom is due to the nature of the species’ prey: birds. The venom needs to act quickly enough to immobilize the prey before flying away or to ward off any potential threats, unfortunately also including researchers.

Life History Traits

B. insularis have been found to mate terrestrially and arboreally around August through September (Marques et al. 2012). This species gives birth to live offspring with an average of 6.5 snakes per litter (Zelanis et al. 2007). Likely due to frequent inbreeding on the small island, intersexes have been found to be prevalent. This is an important factor in the endangerment of the species, as most of these intersexes are sterile (Guimarães et al. 2014).

Population Numbers/Trends/Pools

There are between 2,000 to 4,000 members of the B. insularis population on the Queimada Grande island and most are located toward the center of the island. There are some points on the island that can have up to one snake per meter (Geiling 2014). The Brazilian navy has been reducing the vegetation of the island which affects the area in which the population can flourish (Geiling 2014).

The last monitoring of the B. insularis population was completed in the late 2000s. It concluded that, while critically endangered, the species was stable. This may have changed from then to today as the population has been increasingly affected by human activity and inbreeding as their habitat is condensed.

The B. insularis species has two major known pools, the captive population being held by conservationists and the aforementioned wild population on their native island. “49 specimens belonging to an ex-situ population maintained at the Laboratório de Ecologia e Evolução (LEEV), Instituto Butantan (São Paulo State, Brazil),”(Salles-Oliveira et al. 2020) according to the source, a significant captive population is being held and monitored. This is important as these two populations, while the same species, runs the risk of diverging just as B. insularis did from its common brethren, B. jararaca. This is mainly due to the significant inbreeding that occurs in both the captive and wild populations (attributed to their small and dense numbers). “Isolated, small, and critically endangered populations tend to present low values of genetic diversity and inbreeding occurrence relative to continental or unthreatened populations”(Salles-Oliveira et al 2020).

Population Speciation

The mainland species B. jararaca and B. insularis are closely related and likely come from a recent common ancestor (Barbo et al. 2002). The main anatomical differences between B. jararaca and B. insularis. are the body form and number of scales. B. insularis scales are golden in color and are more slim and slender in appearance, which differs from the darker color and comparatively thicker body of B. jararaca (Barbo et al. 2002). Venom differs between the two as well. The B. jararaca’s venom acts as an anticoagulant, causing excessive bleeding within its prey. In contrast, the venom of B. insularis is corrosive in nature and was important in its evolution to hunt birds before they could fly away.

Just as B. insularis speciated from B. jararaca when isolated in a small, dense island, the B. insularis is not running the same risk on the native island. Rather, the risk is heightened between the captive population at LEEV and the wild population. As the population on the island and in captivity are so small, inbreeding can quickly speciate the two populations. Additionally, being able to remove individuals from the island to homogenize the captive population is extremely difficult, and the captive population is also inbreeding and speciating. “Furthermore, the existence of inbreeding may reduce the genetic fitness in the population, leading, in some cases, to a decline in fecundity and survival rates, as well as sexual abnormalities.”(Salles-Oliveira et al. 2020) According to the source, inbreeding is causing many issues in both populations, and should these abnormalities be reproduced further within their populations, speciation will occur even faster.

Medicinal Value

Most sources never mention B. insularis by name as a contributor to already developed medicine; however, sources frequently mention many of its close relatives such as B. jararaca, Bothrops asper, Bothrops atrox, and Bothrops alternatus. This is especially interesting as it suggests that thorough research (in terms of medicinal value) has not yet been conducted on B. insularis. But the fact is that B. insularis’ close relatives have been proven useful in this field means that B. insularis very well could too. The study of B. insularis snake venom that has been conducted so far is underdeveloped, to say the least, but two parts of the venom have been found to be useful or at least could show potential within the medical field. C-Type Lectin can be isolated from the B. insularis snake venom, and it has a variety of uses in medical practice serving as an anticoagulant and has ‘platelet modulating’ properties (Braga et al. 2006). These C-Type Lectin proteins are found in many animals, and the lectin proteins extracted from B. insularis have similar effects as other snakes within the Bothrops genus. In addition, researchers affiliated with the Federal University of Ceara have extracted and found biological effects from the L-amino acid oxidase found in the venom of B. insularis (Braga et al. 2008). The team is the first to analyze this amino acid within B. insularis venom leading the way with a valuable piece of research within this underdeveloped field. The L-amino acid oxidase is used to activate platelets within the blood and help slow blood flow in the affected region. When introduced to a rat kidney, the L-amino acid oxidase allowed for increased filtration and tubular reabsorption, a property that could temporarily help kidneys function better (Braga et al. 2008).

Cultural Value

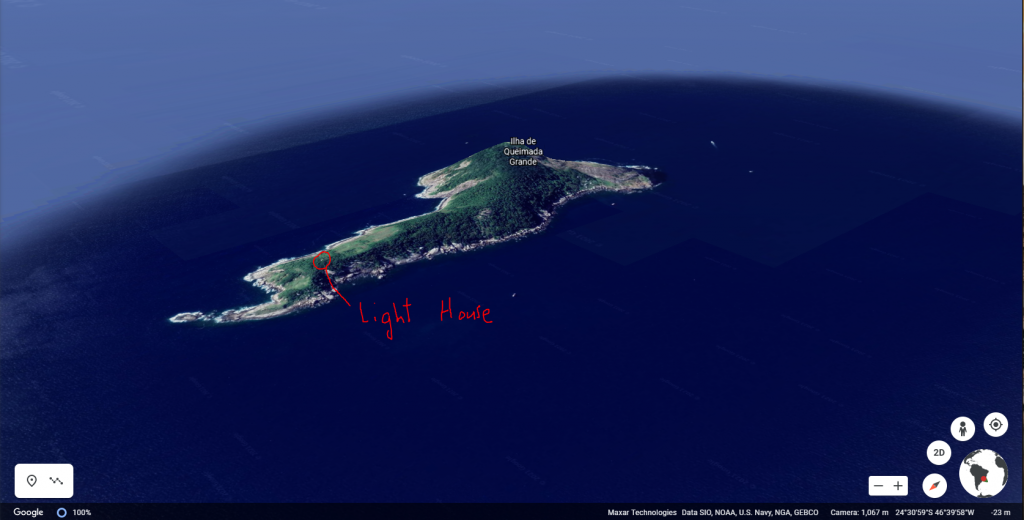

Aside from the potential medicinal value of the snake, the snake, in tangent with the island itself, has a cultural value in Brazil apparent through the stories told of them. There are three that appear to be most popular and widespread. They include a story of pirates who hid treasure long ago on the island and then let free hundreds of venomous snakes to guard it, a story of a family of lighthouse keepers who were all found dead after snakes made their way into the lighthouse, and finally a story of a fisherman who came onto the island in search of food and was later found on his boat in a pool of blood adrift in the ocean (Dimuro 2018). These stories demonstrate the horror and mystery that surrounds the island in Brazilian culture, proving the island and its snakes to be a phenomenon that, while understood to simply be an island of many poisonous snakes, would be a cultural blow to Brazil should they not be preserved. While fear of the island is mostly attributed to fear of the unknown, researching these snakes is no easy feat. As these snakes are some of the most poisonous in the world, it is difficult to study and preserve due to the dangers of the island. Just going to the island requires special equipment and personnel to bring a level of safety. A video called “ Take a Trip to Brazil’s Snake Island: Home of the Golden Lancehead Pit Viper” showed a reporter and researchers going to and traversing snake island. From this video, you could see some of the equipment they use, most notably foot and shin armor. Additionally, it appeared that there was a person who stayed on the boat in the case of an emergency and they needed to leave quickly. A person has at most 6 hours to live after a snake bite, but living that long after a bite from B. insularus is extremely rare (ABC News 2014).

Conservation Efforts

B. insularis has been labeled critically endangered by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) as the population size is extremely small and inhabits a singular, small island off the coast of Brazil. As the human presence, in the form of the Brazilian navy and lighthouse staff, continues to degrade the island’s already limited habitat, the species risks dwindling further. Snake venom has an abundance of research potential and thus the species is very desirable to keep afloat.

The Brazilian government has completely shut off the island to any visitors and the navy is in charge of enforcing this restriction. The government, however, is causing habitat degradation as they attempt to maintain a lighthouse on the island. Not only this, but they are also clearing some of the vegetation around the island and it could only be imagined this is for safety reasons. This habitat loss could be very impactful since the land the species lives on is very small to begin with. Anti-poaching measures are in place but appear to not be very effective. They mainly consist of cameras, but there is not much stopping a poacher from sneaking in. Additionally, no one is on the island to monitor potential poaching (Brethauer 2018).

As mentioned before, there is a captive population that is used not only for research purposes but also to be used in the case of reintroduction on the island. For this reason, conservation efforts need to focus on keeping the two population’s gene pools homogenous for that possibility. Consistent interbreeding, while also preserving the native population (through the measures mentioned above), is extremely important for future conservation efforts.

Bibliography

ABC News. 2014. Take a trip to Brazil’s Snake Island: Home of the golden lancehead pit viper. [Internet] YouTube.com. [cited 2021 March 11] Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PVA6hU-wDZ0

Barbo FE, Grazziotin FG, Sazima I, Martins M, Sawaya RJ. 2012. A new and threatened insular species of lancehead from southeastern Brazil., Herpetologica 68(3): 418-429. https://doi.org/10.1655/HERPETOLOGICA-D-12-00059.1

Brave wilderness. 2020. Human blood vs. snake venom! [Internet]. YouTube.com. [cited 2021 March 11] Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1Nyc8X8Ru8

Braga MD, Martins AM, Amora DN, de Menezes, DB, Toyama MH, Toyama DO, Marangoni S, Barbosa PS, de Sousa Alves R, Fonteles MC, Monteiro HS. 2006. Purification and biological effects of C-type lectin isolated from Bothrops insularis venom. Toxicon 47(8): 859–867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.02.016

Braga MD, Martins AM, Amora DN, de Menezes DB, Toyama MH, Toyama DO, Marangoni S, Alves CD, Barbosa PS, de Sousa Alves R, Fonteles MC, Monteiro HS. 2008. Purification and biological effects of L-amino acid oxidase isolated from Bothrops insularis venom. Toxicon 51(2): 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.09.003

Brethauer A. 2 December 2018. 25 things about Snake Island that we preferred not to know. TheTravel. [Internet] [cited 2021 March 11] Available from: https://www.thetravel.com/things-about-snake-island/

Cañas CA, Castaño-Valencia S, Castro-Herrera F, Cañas F, Tobón GJ. 2021. Biomedical applications of snake venom: From basic science to autoimmunity and rheumatology. Journal of Translational Autoimmunity 4(3): 100076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtauto.2020.100076

Dimuro G. 27 June 2018. An island in Brazil has so many snakes that humans aren’t allowed on it — and it’s the stuff of nightmares. Business Insider. Available from: https://www.businessinsider.com/an-island-in-brazil-has-so-many-snakes-that-humans-arent-allowed-on-it-and-its-the-stuff-of-nightmares-2018-6

Geiling N. 25 June 2014. This terrifying Brazilian island has the highest concentration of venomous Snakes anywhere in the world. Smithsonian Magazine [Internet]. [accessed 2021 Mar 4]. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/snake-infested-island-deadliest-place-brazil-180951782/#:~:text=Brazil’s%20Ilha%20de%20Queimada%20Grande,deadliest%2C%20and%20most%20endangered%2C%20snakes&text=From%20Iguazu%20Falls%20to%20Len%C3%A7%C3%B3is,breathtakingly%20beautiful%20places%20in%20Brazil

Guimarães M, Munguía-Steyer R, Doherty PF Jr, Martins M, Sawaya RJ. 2014. Population dynamics of the critically endangered golden lancehead pitviper, Bothrops insularis: Stability or decline? PLOS One 9(4): e95203-e95203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095203

Marques, OAV, Martins M, Develey PF, Macarrão AF, Sazima I. 2012. The golden lancehead Bothrops insularis (Serpentes: Viperidae) relies on two seasonally plentiful bird species visiting its island habitat. Journal of Natural History 46(13-14): 885-895. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2011.654278

Salles-Oliveira I, Machado T, Banci KR da S, Almeida-Santos SM, Silva MJ de J. 2020. Genetic variability, management, and conservation implications of the critically endangered Brazilian pitviper Bothrops insularis. Ecology and Evolution 10(23): 12870–12882. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6838

Zelanis A, de Souza Ventura J, Chudzinski-Tavassi AM, Furtado dFD. 2007. Variability in expression of Bothrops insularis snake venom proteases: An ontogenetic approach. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 145(4): 601-609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2007.02.009

A strategy consisting of multiple short, high-speed chases of multiple medium-sized prey rather than long-distance.

Cold-blooded animals including fish, amphibians, reptiles, and invertebrates.

To live in the trees.

Major ecological community types (i.e. tropical rain forest, grassland, or desert).

Found only in a particular geographical location

A copious or heavy discharge of blood from the blood vessels; a rapid loss of blood.

Breed from closely related animals, especially over many generations.

According to the IUCN, critically endangered species are those that face an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.

The formation of new and distinct species in the course of evolution.

A substance that hinders the clotting of blood, which makes the blood thin.

To make uniform or similar.

The process that moves solutes and water out of the filtrate and back into the bloodstream.

A set of processes by which habitat quality is reduced.