8

Allison Walker, John Puksta, and Lorenzo Lopez

Abstract

The overexploitation of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) stems from its highly demanded medicinal properties. Through research gathered in field studies about population distribution and information about the ecological life cycle provided by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), conservation policies have been developed to help address the status of the American ginseng. This chapter discusses the historical and economical aspects of the American ginseng and then explains how distribution and predatory factors influence conservation efforts.

Historical

The discovery of American ginseng is accredited to two French Jesuits. With the assistance of Native Americans, in 1716, Jesuits discovered the American ginseng . The Native American tribes would utilize different parts of the ginseng to treat various ailments. For example, the Muscogee tribe would use a poultice containing the ginseng’s root to prevent continued bleeding and a tea for respiratory infections (Stevenson 2019). American ginseng is believed to possess cooling and moistening properties. The most prevalent uses of ginseng are in Chinese medicine and Western herbal tradition.

The Chinese began to trade American ginseng in 1718. By 1751, China was importing enough American ginseng from Quebec that the Company of the Indies [1] monopolized the market for these roots. The first recorded mention of the American ginseng as a medicinal herb was detailed in ”Ben Cao Gang Mu Shi Yi”.[2] This publication consisted of over 800 medicinal texts with an additional working experience of 30 years in the field. Nearly 200 years later, the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China published the first edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia[3] in 1953. By 2000, the American ginseng was added to this resource. For over 300 years, China has used the American ginseng in traditional medicinal practices including the “daodi” ginseng, which has acclimated to the Northeastern Provinces, Beijing, and Shandong (Brinckmann and Huang 2018).

Economical

Prices of the American ginseng were once $200 per pound, but as of 2016, the threat of over-harvesting and poaching from Chinese consumers have caused the ginseng to rise to a staggering $1,000 per pound. Unfortunately, the ginseng’s special importance to Chinese natural medicine combined with raised prices have further provoked poaching of the plant. In Chinese culture, the American ginseng root is used for medical care and they find the shape of the root to be very important in dictating what the root is used for. More ideal shapes (Figure 1) bring in more money from Chinese consumers (Arnold 2016).

Range and distribution

American ginseng can be found across the Midwest United States, throughout the Northeast, and into Eastern Canada (Figure 2). The species’ endemic habitat is cool woods with ideal soil conditions ranging from moist, organic, and enriched humus (Panax quinquefolius 2019). Ginseng grows best in a climate with a range of 70% to 80% shade with 40 to 50 inches of annual rainfall and a climate temperature of about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. The American ginseng is adapted to handle occasional canopy disturbances (Wulfsberg 2019). Warmer environments due to climate change have negatively impacted the viability of the American ginseng because they have adapted to grow within a relatively narrow temperature range. However, early warming periods during the late winter give rise to a dangerous threat, cold arctic blasts that bring harmful frost that damage plant tissue (Souther 2011).

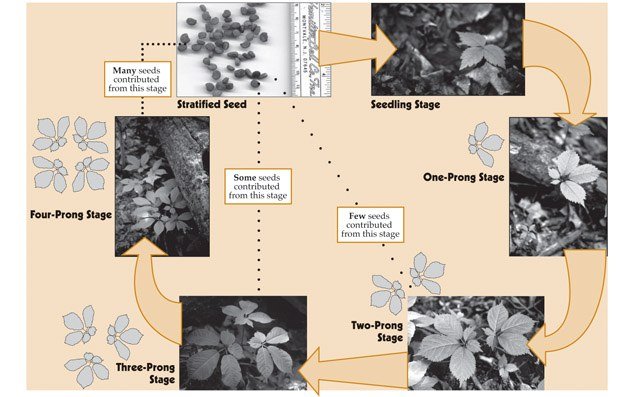

The survival rate of the American ginseng is directly correlated to its size. Smaller plants are observed to have a 69-92% higher annual mortality rate. These plants are expected to be around 12 to 15 centimeters with reliance on their respective harvest intensity indices (Wulfsberg 2019). This species has a long life cycle, which results in a low amount of mature American ginsengs that bear healthy roots. Seed propagation rates are fully dependent on the maturity of the ginseng, as its first germination will produce small seed amounts with subsequently increasing amounts as it matures (Vaughan et al. 2011). Figure 3 provides additional information regarding the production of seeds.

The germination period for American ginseng requires 18 to 20 months in a temperate climate because this aids in maturing the seeds (Harrison et al. 2021). The American ginseng experiences a morphological dormancy, one of five dormancies that seedlings can undergo. To wake the ginseng from this, it is necessary that there is a series of cold and warm temperatures (Emerald Castle Farms 2016). Ginseng germination requires them to survive for a minimum of two years before they are eligible to produce seeds (Harrison et al. 2021). This specific type of dormancy can be harmful to struggling populations, as newly planted seeds will not show activity until this period is over. However, this also serves to protect budding seeds. If seed were to bud in early fall it would not survive since the time to develop a sustainable root is too great. Additionally, this dormancy makes it difficult to artificially reproduce, strengthening the need to protect young ginseng so that they may produce seeds on their own.

In 2009, a study from 1996 to 2006 was analyzed to measure the relationship between harvesting and population growth of the American ginseng, with information on the population size and harvest index measured for each of the 12 populations studied. The populations were experimentally harvested upon, and the intent was to provide an understanding of how harvesting affects ginseng population growth. It was found that the initial stage composition of the American ginseng in 1996 had not recovered its diversity 10 years later in 2006, which suggests a noticeable loss in genetic diversity (Mooney and McGraw 2009). The distribution and population of the American ginseng were seen to be heavily affected by harvesting, which is why conservation policies have been developed.

Predatory Factors

Massive over-harvesting has caused the rapid decline of American ginseng within the past 40 years. NatureServe Explorer has given them unofficial classification as a “vulnerable” species, as the IUCN Red List has not yet assessed the American ginseng. Along with over-harvesting, this herb is threatened by a variety of species because the American ginseng serves as a food source within its ecosystem. Increased numbers of turkey populations near American ginseng populations have contributed to the uprooting of these plants proven by clear scratch marks on their stalks. The white-tailed deer, an herbivore of juvenile American ginseng, generally eats the above-ground portions of the plant, which includes but is not limited to the leaves, reproductive structures, and stalks. Conversely, rodents will interfere only with the ginseng’s roots through excavation. Some rodents such as shrews are suspected to be predators of seeds and berries of the American ginseng. Insects such as stink bugs play a double role by preying on the ginseng’s fruit and seeds and also being a pollinator (McGraw et al. 2013).

It is difficult for naturally occurring ginseng in the wild to mature for five years because there are many predators that consume this plant. Due to this and damage assisted by human-induced habitat destruction (Schmidt et al. 2019), it is essential that American ginseng farmers choose an area[4] away from constant foot travel that would disrupt the seed growth (Arnold 2016). For instance, in areas that support heavy deer populations, there is a visible reduction of ginseng in the following year (Hruska 2014). If over-harvested by deer and other small mammals, there is a strong possibility that the ginseng may not recover. Browsed plants, including the ginseng, do not support seeds[5] as they die off (Vaughan et al. 2011). However, the seed embryos are protected from harmful digestive enzymes and survive until they are excreted (Vaughan et al. 2011). Newly deposited seeds are found near topsoil in a nutrient-rich environment creating an ideal scenario for them to develop and mature. Not only does this diversify a forest’s population of ginseng but it also protects ginseng from localized extinction.

Conservation efforts

The delayed maturity of the seeds coupled with an extensive history of over-harvesting has put this species on the endangered list for many states. To combat over-harvesting of American ginseng, it is only legal to harvest during specific time periods and the ginseng must be five years or older (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2021). Within Pennsylvania, ginseng has been historically documented to be found within each of the 67 counties from the early 1700s with protection measures implemented as early as the late 1800s. Pennsylvania allows American ginseng to be harvested from September 1st to November 30th. It is protected from April 1st to September 1st. This allows American ginseng to reach a mature stage where they are able to set seed for the next season.

The USFWS is hopeful that the plant could make a comeback with the positive promotion of ginseng cultivation and legal trade enforcement. American ginseng trade is regulated under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Many precautions have been taken to ensure proper harvesting of the American ginseng. When an American ginseng plant is harvested, it is done in a manner that will allow it to continue its growth and reproduction. The roots must be sold to a certified dealer within the state that they were harvested from. Dealers that make successful sales and purchases must keep a detailed history of their transaction records (Vaughan et al. 2011). American ginsengs are prone to poaching; thus, ginseng farmers have taken measures to protect their crops, such as surveillance cameras and guard dogs. Along with this, Appalachia is funding agroforestry to help maintain its species biodiversity, which includes the American ginseng (Hoffner 2019). The American ginseng appears to have the most successful growth in national forests, national parks, and state-owned land where it is best protected from poaching (Schmidt et al. 2019).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Professor Marja Bakermans and PLA Urmila Mallick for advising us through this project and administrating a wonderful biodiversity course!

References

American Ginseng. n.d. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.fws.gov/international/plants/american-ginseng.html#:~:text=American%20gi nseng%20(Panaz%20quinquefolius)%20is,and%20also%20in%20eastern%20CanaDa

Arnold C. 2016. As demand for ginseng soars, poachers threaten its survival. National Geographic. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/with-demand-for-ginseng-high–poachers-threaten-its-survival

Brinckmann J, Huang L. 2018. American ginseng a genuine traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of History of Medicine 30(3): 907-928..

Burkhart E, Jacobson M. 2011. American ginseng [Internet]. Penn State Extension. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://extension.psu.edu/american-ginseng

Castle B. 2016. Ginseng seed dormancy and delayed germination…in plain English [Internet]. Emerald Castle Farms. [cited 2021 Feb 24]. Available from: http://emeraldcastlefarms.com/Articles/SeedDormancy.html

Ha K, Atallah S, Benjamin T, Farlee L, Hoagland L, Woeste K. 2017. Costs and returns of producing wild-simulated ginseng in established tree plantations. Purdue Extension. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.fs.fed.us/nrs/pubs/jrnl/2017/nrs_2017_ha_001.pdf

Harrison HC, Parke JL, Oelke EA, Kaminski AR, Hudelson BD, Martin LJ, Kelling KA, Binning LK. 2021. Ginseng in Alternative Field Crops Manual, University of Wisconsin-Extension and University of Minnesota Extension Service [Internet]. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/afcm/ginseng.html

Hoffner E. 2019. Agroforestry program in Appalachia receives $590,000 in federal funding [Internet]. Mongabay. [cited 2021 Mar 4]. Available from: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/11/agroforestry-program-in-appalachia-receives-590000-in-federal-funding/

Hruska AM. 2014. Animal dispersal of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) [dissertation]. West Virginia University. 82 p. Available from: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1618&context=etd

Long Live American Ginseng!. n.d. U.S. Forest Service [Internet]. Washington DC: US Forest Service. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/Native_Plant_Materials/americanginseng/index.shtml

McGraw JB, Lubbers AE, Van der Voort M, Mooney EH, Furedi MA, Souther S, Turner JB, Chandler J. 2013. Ecology and conservation of ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) in a changing world: Ecology and conservation of ginseng. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1286(1):62–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12032

Mooney EH, McGraw JB. 2009. Relationship between age, size, and reproduction in populations of American ginseng, Panax quinquefolius (Araliaceae), across a range of harvest pressures. Écoscience 16(1): 84-94. https://doi.org/10.2980/16-1-3168

Panax quinquefolius. 2019. PLANT DATABASE [Internet]. Austin (TX): Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=PAQUk.

Schmidt JP, Cruse-Sanders J, Chamberlain JL, Ferreira S, Young JA. 2019. Explaining harvests of wild-harvested herbaceous plants: American ginseng as a case study. Biological Conservation 231: 139-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.006

Souther S. 2011. Demographic response of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) to climate change [dissertation]. West Virginia University. Available from: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5830&context=etd

Stevenson A. 2019. The mysterious powers of American ginseng [Internet]. Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Available from: https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/mysterious-medicinal-economic-powers-american-ginseng

USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab. 2018. Panax quinquefolius 2, American ginseng root. [cited 2021 March 17]. Available from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/usgsbiml

Vaughan RC, Chamberlain JL, Munsell JF. 2011 Growing American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) in forestlands. Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Virginia Cooperative Extension. Available from: https://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/354/354-313/354-313.html

Wulfsberg M. 2019. An overview of American ginseng through the lens of healing, conservation and trade [ honors project]. Appleton (WI): Lawrence University. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. Available from: https://lux.lawrence.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1154&context=luhp.

- Exporter of American ginseng roots. ↵

- A historical text published in 1765 ↵

- Descriptions of traditional Chinese medicine, Western medicine as well as a compendium of drugs including their classifications, strength, and precautions. ↵

- Since the American ginseng requires specific light and soil requirements, it is ideal to grow it in either a wild-simulated or native environment. ↵

- Seeds of ginseng are three to five millimeters in length with a hard seed coat. ↵

Moist material that is typically created from plant material or flour, customarily applied to parts of the body to aid in inflammation. It is kept in place by a cloth wrapping.

Found only in a particular geographical location

Used to describe the relationship between the species size and the ratio of harvested to total amount of the plant.

Plant development process from a seed after a time of dormancy

Embryos of the seeds that have yet to differentiate into different tissues at the time of the fruit ripening.

Life cycle stage in relation to its expected seedling appearance

The variation of genetic information within a population/species.

International Union for Conservation of Nature

a predator that only eats plants

Agriculture involving the conservation and cultivation of trees