5

Andrew Hariyanto, Gautham Rajeshkumar, James Tasto, and Valerie Bennett

Abstract

Approximately 1 billion bird collisions happen in North America yearly, and Chicago is the city where most incidents happen. Consequently, Chicago has solutions to reduce bird collisions, and our goal is to explore both Lights Out Chicago and bird-friendly window designs as viable solutions. Our findings conclude that the two programs have an impact on bird collision fatalities in the city, making both solutions viable and beneficial for bird collision reduction. This chapter discusses several possible improvements for the solutions including the reporting of the solution’s status on a city-wide scale, providing more incentives, and increasing public awareness.

What is the Issue?

Urbanization is the essence of anthropogenic drivers of extinctions as all man-made structures are obstructing and altering the very lifestyles of living organisms. Of these living organisms, birds are among those that die as a direct result of urbanization as they tend to collide with buildings. Even though collisions with buildings are not considered as a high-threat driver of extinction, it is “an added burden for populations already in decline for other reasons” (Arnold & Zink, 2011). The leading research questions to address this problem include: what exactly are the main drivers of bird collision, which area has the highest number of bird collision fatalities, and does the problem have any solutions? Consequently, this project narrowed down the scope to Chicago and the solutions that have been implemented there. This project has the potential to advance knowledge in areas of ecology and urban animal conservation. The major focus of this project is on birds. By emphasizing the dangers that these birds face in an urban setting, it can inspire more research to see how other flying species like bats are affected. Additionally, one of the research methods conducted in the project emphasized the importance of city-wide reports. Similar methods could be used for many urban conservationists to create unique, multi-faceted reports from economic, ecological, and geographic perspectives. This comprehensive data will map out a wide array of implications that urban conservation solutions have on the area it is implemented in.

Lights and Windows – A Deadly Combination

Lights and windows are the two biggest drivers that result in bird collisions. How exactly do these two seemingly unharmful objects cause an estimated 1 billion bird deaths in North America (Briscoe & Damier, 2019)?

Bird species, especially migratory ones, use light as a visual cue to navigate (Gauthreux & Belser, 2005). When they see a glow on the horizon because of a concentration of city lights, they will be attracted to it. Data from many studies have shown that there indeed was a correlation between the number of birds present in the area and the amount of light being emitted (Gauthreux & Belser, 2005; University of Delaware, 2018; Van Doren et al, 2017). Lights disorient the bird’s internal geomagnetic compass and causes them to stray from their straight migratory flight path. They end up circling around the light source, expending huge amounts of energy (The City of Chicago, 2020). During that time, they become vulnerable to collisions with buildings, the surrounding environment, and even other birds that are attracted to the source (Horton et al, 2019). Birds that have successfully evaded the physical obstacles, however, are forced to rest and recover the lost energy from circling the light source in the city itself. This can potentially cause further risk to the birds as they can still collide with buildings the next day (Furuya, 2017).

The detrimental effect of light exposure is not only limited to lights in the exterior of buildings, however. Especially in Chicago where the skyline is dominated by glass buildings, interior light that penetrates the glass into the night sky can cause many fatalities (Briscoe & Damier, 2019). Birds cannot see glass and, thinking that they can directly go to the light source, collide with some invisible wall. Even without the addition of lights, windows still pose a threat. This is not only because birds can’t see windows, but because of what might be near windows. Many collisions with windows would not happen unless the bird finds something appealing on the other side, such as a tree or bush to sit on. Seeing a reflection of vegetation makes the bird think that there is more place to rest, leading them to take the path to the window. Furthermore, most birds have eyes on the sides of their heads, which gives them a wide field of view for predators. However, this added benefit comes at the cost of not seeing depth, which is why they are easily fooled by reflections of vegetation (EarthSky, 2017). Birds not being able to see this sort of depth as we do makes it harder for them to differentiate physical from reflected vegetation.

In a Chicago Tribune article, conservation ecologist Douglas Stotz summarizes, “The windows are what kills them, the light is what brings them into danger” (Briscoe & Damier, 2019).

Chicago – A Trap In Disguise

Spanning a total of 288 square miles, Chicago is a city known for its magnificent architecture and city life (Schallhorn & Duis, 2020). However, Chicago is also very notorious for being a dangerous city for birds. Every year, it is estimated that 5 million birds migrate through the city on their way to their breeding habitats, and approximately 6,000 bird fatalities occur per square mile (Briscoe & Damier, 2019). The reason why Chicago is such a dangerous area is because of its light emissions at night, as well as the nature of its architecture. Chicago is the city with the highest light emissions in the United States, ranking above Houston and New York City (Horton et al, 2019). Many of the buildings also have windowed surfaces (Briscoe & Damier, 2019). Through a bird’s eyes, it is like going through an invisible maze. Because of how vulnerable birds are to lights and windows, it is not surprising that Chicago is ranked as the most dangerous city for birds to fly through (Horton et al, 2019). This is the reason why Chicago was chosen as the scope of this project (Figure 1).

Our Methods

Because the two biggest drivers are lights and windows, we found solutions that directly address them: Lights Out Chicago and bird-friendly window designs. After narrowing down our scope to the Lights Out program and bird-friendly window designs in Chicago, the next step is the analysis of these two solutions to determine whether they have an impact on bird collision rates. In order to do this, we determined three steps that must be done for both Lights Out Chicago and bird-friendly window designs. First, there must be a clear explanation on what the solution details. This includes guidelines as well as the theory behind the implementation of the solution. Second, the analysis of the impact of the solution on bird collision rates will be done. For Lights Out Chicago, a combination of existing studies, reports on the implementation and effect of the program, and news articles will be used. Because Lights Out is a large program, its reports will be useful in gaining in-depth information. Chicago is also fairly famous for its Lights Out program and media attention through news articles definitely can widen our pool of information. For bird-friendly window designs, existing studies would be used to determine which window designs would be most impactful, as well as whether removing surrounding vegetation has an effect on bird collision rates. Through this process, we can determine if the two solutions are viable. Lastly, we would also develop improvements based on our findings in the previous steps.

Lights Out Chicago – Dark Is The New Light

Lights Out Chicago

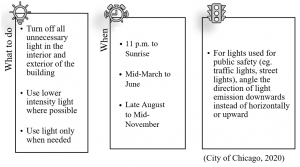

Considering that Chicago is the city with the highest light emissions in the United States, it is a no-brainer that Chicago became the first city in the United States to implement a Lights Out program (Bird Collision Monitors, 2012). Starting in 1995 by the Chicago Audubon Society, Lights Out Chicago has been trying to raise awareness on the impact that artificial light has on migrating birds and promote the idea of a city-wide minimization of light emission during important migratory seasons (The City of Chicago, 2020). Building owners and managers can opt to join in on this program by following guidelines that the organization has set up (Figure 2).

As can be seen in the guidelines, buildings should aim to limit as much interior and exterior light as possible, especially those that are solely for the purpose of decoration. Most decorative lights are flashy and bright in nature and are the most dangerous for birds. Buildings do not have to follow this year-round, but only during the spring and fall migration as that is when bird fatalities are greatest (Bird Collision Monitors, 2012). The period of time where it is guaranteed that lights are not needed is 11 P.M. to sunrise. By turning off the majority of lights during this time, many of the migratory birds will not be ensnared by the lights (Bird Collision Monitors, 2012). Lights Out Chicago is voluntary which means that it requires the public’s participation as well. Unfortunately, there are many that say that lights are an integral part in making the aesthetics of the city beautiful, leading to some resistance (Villagomez, 2019). Figure 3 shows the Lights Out program in effect.

Analysis on the Impact of Lights Out on Bird Collision

A study done by Field Museum scientists at the McCormick Place in Chicago aimed to see the number of bird fatalities in response to whether windows were lit or dark (Appendix 1). The infamous McCormick Place was the site where half of the collisions in Chicago occur (Foderaro, 2019). When all windows were dark, there was an estimated 88% decrease in bird collisions, and when there was a mix of both lit and dark windows, there was an overall 83% decrease in bird collisions once variances in lighting conditions have been accounted for (Field Museum, 2002).

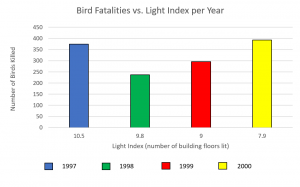

Unfortunately, Lights Out Chicago has not conducted a city-wide report on the current success and status of the program, but there are other places that have implemented a Lights Out program. Another city that has done extensive research into the impact of a Lights out program is Toronto. The Fatal Light Awareness Program (FLAP) conducted a city-wide study from 1997 to 2001 analyzing the effect that their Lights Out program had on bird collision rates (Evans Ogden, 2002). Because Chicago and Toronto share many of the same migratory bird species (School of Environment Sustainability, 2014; Birds of Toronto Working Group, 2011), this study by FLAP can potentially be used to map out the effectiveness of Chicago’s Lights Out program. Appendix 2 summarizes the bird collision and light emission data that FLAP gathered over a 4-year period at 16 buildings, and Figure 4 is a representation of the data.

Although it may seem as though decreasing light emission has no effect on decreasing bird collision rates, it must be pointed out that there are other variables that affect the number of birds passing through the city. Such variables include climate change, success of the breeding season, etc. (Miller-Rushing et al., 2008). The data in the graph does not accurately portray the effect of decreasing light emission on collision rates.

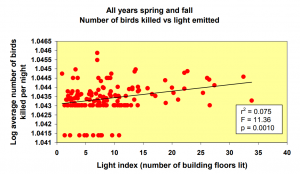

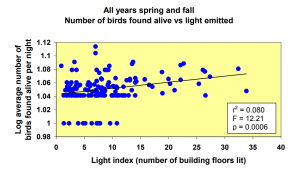

To compensate for the many factors influencing collision frequency, the study combines data of birds killed (or birds found alive near the area from all the days during the fall) and spring migration. This data is then plotted against the light index of buildings where each data value was taken. The graph in Figure 5 shows the data of birds found alive against light emission. These birds are considered as those that were forced to rest after being attracted to a light source and circling around it for extended periods of time. The graph in Figure 6 shows data of birds killed against light emission. Through the information discussed, the study found that “the number of fatal bird collisions increases with increasing light emissions” and that “the number of birds entrapped by lights emanating from particular buildings increases with increasing light emissions” (Evans Ogden, 2002).

Both studies done by the Field Museum and FLAP showed a positive relationship between light emission and bird collision, thus reinforcing the Lights Out program as a viable solution to decrease bird collision fatalities. However, the estimated 83% decrease in collisions from the Field Museum is not reflected in the graphs provided by the FLAP study. In Toronto, there seems to be much less than 83% reductions in collisions. This could be due to the different geographic areas in which they are located. It could also be attributed to the fact that the FLAP study incorporated data from 16 buildings all over the city, while the Field Museum study only used data from the McCormick Place. Geographically, the McCormick Place is a relatively isolated building, making it the brightest building in the area. It does not have other surrounding buildings with high light emissions, while the 16 buildings in Toronto do. Regardless, a program like Lights Out Chicago, whose sole purpose is to decrease light emissions in the city, will be effective in mitigating bird collisions in the future.

Improvements

There are some possible improvements that could be done based on the studies that were analyzed. First, unlike FLAP in Toronto, Lights Out Chicago does not have a city-wide report that maps out the effectiveness of the program so far. In order to see trends specific to Chicago only, a study must be done at that location. Although there was a study done at McCormick Place, it is only one building and does not provide as comprehensive a report as one that is large-scale. As information and data are essential in measuring progress, a possible next step for Lights Out Chicago is to conduct that report. Also, the reports are not recent, and a newly updated account will help in providing more current information. However, to conduct reports that are dependent on a data set derived over a period of years, it is very difficult because, as shown in Figure 4, the number of birds migrating per year fluctuates. This report must have a method that is independent of the years focusing only on the relation of collisions with light index. Second, Lights Out Chicago is voluntary, and building managers participate at their own accord. Another improvement to Lights Out Chicago would be to further incentivize the program. According to the study done by FLAP, seven of the building managers commented on the savings and cost-efficiency now that most of the lights are dimmed at night. One building was able to save 200,000 CAD per year (Evans Ogden, 2002). These cost savings could potentially become a huge incentive that buildings managers would consider. Lastly, Lights Out Chicago would greatly benefit from spreading more awareness of the situation. It was mentioned that there are some that resisted the idea of Lights Out Chicago, but with more awareness of the problem and as more people join in, the resistance will gradually fade.

Bird-Friendly Window Designs – Seeing The Invisible Wall

Analysis of the effect window designs have on birds (BFWD)

There are two aspects of BFWD that need to be addressed, one with the window designs themselves and the other with vegetation changes. One of the solutions is with creating patterns in the windows, whether that is with stripes or dots. The purpose of this solution is to prevent the birds from entering the window by closing the path for the birds to enter through. Instead of seeing an invisible wall, birds see the patterns and avoid them.

One of the studies conducted by Christine Sheppard and her team tests what types of patterns on windows birds will try to go through or not go through. They would take some birds to a tunnel specifically created to test how effective certain types of patterns were. In the tunnel, the birds see two pieces of glass: one piece has a pattern and the other is a plain piece of glass. Once in the chamber, they observe which glass the birds try to go through in order to determine if the pattern is effective.

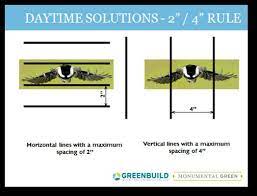

One important finding in the study is that vertical stripes that are at least ¼ inch wide with a maximum spacing of 4 inches, and horizontal stripes that are at least ¼ inch wide with a maximum spacing of 2 inches have been effective at preventing strikes of most birds (Sheppard 2011; Klem 2009). Analyzing the data found in the study, 94% of the flights tested with horizontal stripes went to clear windows while only 90% of flights tested with vertical lines went to clear windows. Both of these findings show how effective patterned windows can be when it comes to decreasing bird collision (Figure 7).

Analysis of the effect of surrounding vegetation on birds

There is a strong correlation between vegetation changes and bird collision frequencies near a building (Loss et al., 2019). Examining the situation, it makes logical sense that this would be true since the reason why a bird might accidentally hit the window is that it is attracted to a tree or shrub that is either reflected by the window or can be seen through the other side.

We can reference a study conducted by Scott R. Loss and his team which assessed factors influencing bird-building collisions in the downtown area of a major North American city (Loss et al., 2019). The study was conducted in downtown Minneapolis, Minnesota which is near an important migration area for birds. 20 buildings were selected for monitoring of bird collisions, 16 of which were in downtown Minneapolis. This study looked at the effect building size and the surrounding vegetation has on bird collision frequencies. To put it in simpler terms, they found that a smaller building with some vegetation has a more detrimental impact on birds than a larger-sized building with no vegetation surrounding it.

The most effective and best solution is to remove some surrounding vegetation or limit the vegetation near windows. It is best to avoid creating an effect where landscaping funnels birds towards glass panes (e.g., walkways, passageways, edges), or where approaches to a building (vehicles or people) flush birds towards windows(U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2016, January). Furthermore, shrubs, plants, or any sort of vegetation near windows should be moved, if possible, farther from the window so it would be hard to reach for the bird and not as well seen. If none of these methods are possible, it is imperative that some sort of solutions with patterns or decals are created.

Many of these solutions that were mentioned are currently trying to be implemented in Chicago. As of right now, there is an ordinance that is still trying to be passed within the Chicago city. In the ordinance, there will be specific guidelines and requirements that would need to be followed such as “Avoid situations where plantings can be reflected on glass surfaces” and “ specify glass that provides visual patterns for birds that can prevent them from striking transparent or reflective surfaces.” (Prince, 2017). The city of Chicago understands the effectiveness of many of these solutions, as well as understanding where the root of the problem stems from. The ordinance was set to be passed soon in 2020 which will satisfy both birds as well as industries, but due to COVID-19, it might have to be set back.

Improvements

Knowing some of the information, it is evident that many of these solutions are easy and cheap to implement in an urban city. Especially when it comes to the glass designs, many of the buildings can simply add dotted patterns like the building in Figure 8. These very simple solutions will have a positive impact on birds and the overall ecosystem. This might be confusing as to why these are still not implemented or why this is still a problem even though the solutions described are effective. It is because many people are not aware of the problem. Without awareness of the problem, many people, as well as governments, do not see the need to implement solutions, and also it would be hard for other industries to see the need to do so. Another improvement when it comes to solutions is to try not to have decals on windows. Decals especially showing a bird are not going to be helpful even though birds might see it. Some birds are very territorial and seeing just a mere reflection of themselves provokes them to think that a bird is trying to contest it. They will then try to attack it and unfortunately die or become severely injured because they crash onto a window. The last thing we want to improve upon is being able to test out the results of the solutions at a city-wide scale rather than looking at individual buildings once most buildings implement them. Many of these studies’ solutions are only tested in a controlled environment and it is difficult to see the effect they would have on a large group of buildings in a Chicago-like setting. Having this information will make it clearer that these solutions are effective for cities and can be easily implemented.

Final Thoughts

Humanity’s urban development has been causing many issues to birds. Building collisions especially are an added burden to some bird species that currently are in the process of going extinct. However, this burden can be alleviated by implementing the two solutions that are described in this chapter. From both the analyses on Lights Out Chicago and bird-friendly window designs, the two solutions are undoubtedly effective methods in reducing bird collision rates. The findings from this research have many benefits to society because it gives concrete proof that these solutions to bird collisions do work, inspiring more cities to implement similar programs. As more cities take part in this, the number of bird fatalities will decrease. Additionally, our findings also include information on what makes buildings dangerous to birds, raising public awareness on this issue. Furthermore, our findings also show that these solutions can be implemented anywhere. Around the world, all birds are the same. They are attracted to light, and they cannot see windows. It is our responsibility as the creators of these urban structures to make it safe for species like birds. One aspect of the project that was not discussed is how buildings affect other flying species. It would definitely be a step forward to see if other flying species are affected by the driver and if the solutions for birds are applicable to them as well.

References

Arnold, TW & Zink, RM. (2011). Collision mortality has no discernible effect on population trends of North American Birds. PLoS One, 6(9): e24708. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024708

Bird Collision Monitors (2012). History of Chicago bird collision monitors. Chicago Bird Monitors. https://www.birdmonitors.net/History.php

Birds of Toronto Working Group (2011). Birds of Toronto – A guide to their remarkable world. City of Toronto Biodiversity Series. http://torontobirdcelebration.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Biodiversity_Birds_of_TO_dec9.pdf

Briscoe, T. & Dampier C. (2019, April 4). As many as a billion birds are killed crashing into buildings each year – and Chicago’s skyline is the most dangerous area in the country. Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-met-migratory-bird-collisions-chicago-20190402-story.html

City of Chicago (2020). Lights out Chicago. The City of Chicago. https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/progs/env/lights_out_chicago.html#:~:text=The%20Lights%20Out%20program%20encourages,and%20the%20City%20of%20Chicago.

EarthSky. (2017, April 28). Why birds smash into windows. Retrieved December 01, 2020, from https://earthsky.org/earth/why-do-birds-collide-with-windows

Evans Ogden, L. (2002). Summary Report on the bird Friendly Building Program: Effect of Light Reduction on Collision of Migratory Birds. Special Report for the Fatal Light Awareness Program. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/flap/5/

Field Museum. (2002, May 8). Turning off building lights reduces bird window-kill by 83%: Field Museum scientists release data from two-year study. Retrieved from https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2002-05/fm-tob050802.php.

Foderaro, L.W. (2019, April 3) Four decades of building strike records point to ‘super collider’ birds. National Audubon Society. https://www.audubon.org/news/four-decades-building-strike-records-point-super-collider-birds

Furuya, A (2017, October 3). We finally know how bright lights affect birds flying at night. National Audubon Society. National Audubon Society. https://www.audubon.org/news/we-finally-know-how-bright-lights-affect-birds-flying-night

Gauthreux, S.A. & Belser C.G. (2005). Effects of artificial night lighting on migrating birds. In: Rich C and Longcore T (Eds). Ecological consequences of artificial night lighting. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Horton, KG., Nilsson. C., Van Doren, B.M., À La Sorte, F., Dokter, A.M.. & Farnsworth, A. (2019). Bright lights in the big cities: migratory birds’ exposure to artificial light. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 17(4), 209-214. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2029.

Kamin, B. (2020, January 16). Column: Chicago’s skyline is beautiful but it’s killing birds. New York has taken action. So must we. Retrieved December 08, 2020, from https://www.chicagotribune.com/columns/blair-kamin/ct-biz-bird-friedly-building-design-kamin-20200116-dp7ubx4uuvh6pk25l2jhghf33i-story.html

Lee, J. (2016, June 16). How better glass can save hundreds of millions of birds a year. Retrieved December 07, 2020, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/11/141113-bird-safe-glass-window-collision-animals-science/

Loss, S., Lao, S., Eckles, J., Anderson, A., Blair, R., & Turner, R. (2019). Factors influencing bird-building collisions in the downtown area of a major North American city. PLoS One, 14(11), e0224164. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224164

Miller-Rushing, A., Lloyd-Evans, T., Primack, R., & Satzinger, P. (2008). Bird migration times, climate change, and changing population sizes. Global Change Biology. 14. 1959-1972. https://10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01619.x.

Prince, A. (Ed.). (2017). Ordinance. Retrieved December 07, 2020, from https://birdfriendlychicago.org/ordinance

School of Environmental Sustainability (2014). Migratory Bird Species. School of Environmental Sustainability. Loyola University Chicago. https://www.luc.edu/sustainability/initiatives/biodiversity/studentoperationforavianreliefsoar/migratorybirdspecies/

University of Delaware (2018, January 19). City lights setting traps for migrating birds: How birds are drawn to artificial light pollution in urban areas. ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/01/180119125817.htm

Van Doren, B.M., Horton, K.G., Dokter, A.M., Klinck H., Elbin, S.B., & Farnsworth A. (2017). High-intensity urban light installation dramatically alters nocturnal bird migration. PNAS, 114(42), 11175 – 11180. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708574114

Villagomez, J. (2019, May 23). Downtown Chicago lights getting turned down for Earth Hour, bird migration. Retrieved December 11, 2020, from https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-met-earth-hour-chicago-20190329-story.html?int=lat_digitaladshouse_bx-modal_acquisition-subscriber_ngux_display-ad-interstitial_bx-bonus-story

Winger, B.M., Weeks, B.C., Farnsworth, A., Jones, A.W., Hennen, M., & Willard D.E. (2019). Nocturnal flight-calling behaviour predicts vulnerability to artificial light in migratory birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286 (1900). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.0364

Relating to environmental change caused or influenced by people.

Pertaining to the magnetic properties of the Earth.

Spring migratory season starts from mid-March to June

Fall migratory season starts from late-August to mid-November