10

Isaac Garry, Jaya Mills, and Joseph Peregrim

Chapter Summary

The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is an important species to both the environment and the global economy. The largest threat that the species faces is overfishing. This chapter will discuss why the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna needs to be protected and will outline the status of the species throughout the Atlantic ocean. The policies that regulate fishing practices in the western Atlantic with those of the Mediterranean Sea will be compared and their effectiveness in protecting the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna species will be evaluated. Policy change recommendations will be made based on the findings of the research presented in this chapter.

Introduction

The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, Thunnus thynnus, is a majestic creature. It is among the largest and fastest creatures in the ocean and its unique body is unlike other fish. Over the course of 65 million years, evolution has turned the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna into what David Attenborough calls “the ultimate fish” (Hourston, 2019). These fish can grow up to 15 feet in length and weigh over 2,000 pounds over the course of their 35-year lifespan (“Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d). Atlantic Bluefin Tuna are capable of reaching high speeds upwards of 43 miles per hour due to their hydrodynamic shape (National Geographic, 2018). In fact, the teardrop shape of the tuna’s body, with its widest point two-fifths of the distance from head to tail, is the most hydrodynamic shape physically possible to achieve (Hourston, 2019).

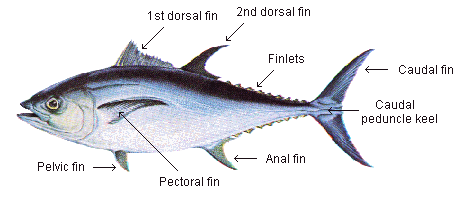

Additionally, Atlantic Bluefin Tuna have developed a specialized method of swimming—thunniform swimming—named after the tuna’s genus. In order to maximize efficiency, the fish’s tail is the only part of the body to move laterally. The tail, or caudal fin, is tall, slender, and stiff. Horizontal keels at its base slice through the water to minimize water resistance as the tail moves side to side (Hourston, 2019). Further minimizing water resistance, most of the fins on a tuna are retractable (National Geographic, 2018). The fins that do not retract, the second dorsal and anal fins, are all narrow and swept back. Retractable fins also allow Atlantic Bluefin Tuna to make more precise movements in the water, which increases the likelihood that a fish lands its prey (Hourston, 2019). Yellow finlets along the back of the tuna serve to break up turbulence and further enable the fish to torpedo through the water (Hourston, 2019; National Geographic, 2018).

Inside the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is just as significant as its exterior. The blood of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna has 2-3 times more hemoglobin than the average fish, and its heart is several times larger (Hourston, 2019). This advantage allows individuals to swim faster, for longer distances, and at deeper depths than otherwise possible. Atlantic Bluefin Tuna also have more red muscle as a percent of body mass than any other fish (Hourston, 2019). Red muscle is used for endurance, which the species needs to migrate thousands of miles every year.

Potentially the most interesting attribute of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is the fish’s ability to regulate its body temperature through a countercurrent heat-exchange system known as a rete mirabile. This system prevents metabolic heat produced by the tuna’s muscles from escaping into the surrounding water. Instead, the heat is absorbed by the cool, oxygenated blood coming from the gills (“Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.). This ability allows the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna to maintain a body temperature between 77 and 91 degrees Fahrenheit, even in the frigid waters of the arctic circle (Hourston, 2019). Maintaining a high body temperature gives Atlantic Bluefin Tuna an advantage over other species in cool waters because it allows the fish’s muscles to function with greater performance and the brain to function more intelligently.

The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is truly magnificent. Unfortunately, it is best known as a food source. The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna fishing industry has a dock value of US $1.6 billion and an end value of US $5.4 billion each year, with the largest markets located in Japan where sushi and sashimi are consumed at high rates (The Pew Charitable Fund, 2020). The high value of the species makes it one of the most sought-after types of fish in the world (“Bluefin Tuna”, n.d.). Because of this, the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna population is constantly under threat by fishermen.

Though it is not considered an overfished species by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, or ICCAT, the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna’s population is far less than it once was (ICCAT, n.d.). Furthermore, the illegal and undocumented fishing of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna pushes the total biomass of tuna caught past international quotas (European Union News, 2018). A decline in the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna population can directly affect entire ecosystems through a process called top-down cascade. In a top-down cascade, a predator at the top trophic level, such as the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, controls the populations of the levels below it. A decrease in the population of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna would therefore cause an imbalance in the surrounding marine communities, causing fluctuations in the abundance and scarcity of all surrounding organisms (Gupta, 2017).

Methodology

To collect information with which to write this chapter, the team first did research on the topic using the online George C. Gordon library and other search engines to find articles. Resources used include species reports, articles, and scientific studies. To get information from a variety of perspectives, the team also conducted interviews with experts on the topic of research. Information about Atlantic Bluefin Tuna from its geographic range was collected so that status and policy could be compared in this research.

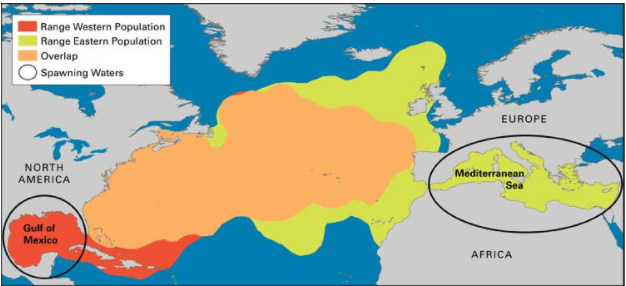

Distinct Populations

Early in the research process, it was found that Atlantic Bluefin Tuna could be divided into two populations: the eastern population and the western population (ICCAT, 2020). The distinction is made based on the location where the tuna breed. Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna generally breed in the Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Atlantic Bluefin Tuna generally breed in the Mediterranean Sea (“Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.). It is important to note that these populations are considered to be of the same species and that most of their geographic ranges overlap as shown in Figure 2 (“Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.). Nevertheless, these populations are impacted differently by different policies in their respective breeding grounds.

ICCAT separates these two populations for management by the 45° meridian (Taylor et al., 2011). Much of the geographic range of the Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, including much of that in which they breed, is along the United States’ coastline. The Eastern Atlantic Bluefin Tuna range throughout the Mediterranean Sea and as far north as the North Sea. This means that the eastern Atlantic range is under the jurisdiction of more countries than the western Atlantic range. Historically, the eastern population of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna has been of greater concern than the western population. However, because of the vast overlap of the ranges of each population, each population inhabits fishing areas regulated by both western and eastern Atlantic countries (ICCAT, 2020). If one set of policies is poor in effect, both populations are harmed.

International Regulation

The organization in charge of the international regulation of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Established in 1966, ICCAT is described as an “intergovernmental” organization, responsible for conserving tunas and similar fish species. The region that ICCAT covers is the Atlantic Ocean and the seas that it borders (ICCAT, n.d.). The ICCAT makes regulations and develops management advice for all fish species across the Atlantic Ocean by using statistics from different fisheries. These statistics include those from research on coordinate locations of fish and stock assessments. Using recommendations from ICCAT, member countries make specific regulations for the regions within their jurisdictions based on population status.

Western Atlantic Status and Regulations

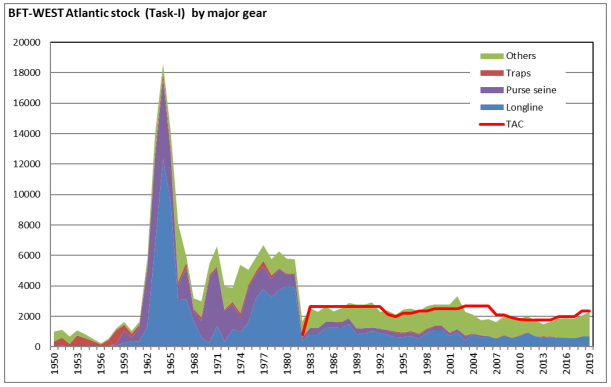

For a better understanding of the status of the Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, historical context is necessary. Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna fisheries began in the middle of the twentieth century (Taylor et al., 2011). The historical range of the western population extended from Canada to Brazil, but in the twentieth century, the species seemingly disappeared from the southern part of its range (Taylor et al., 2011). This disappearance may be explained by the large amount of fish caught by the Japanese longline fishery in the region in the 1960s (ICCAT, 2020). The total catch of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the Western Atlantic peaked in 1964 with a total weight of 18,608 metric tons, most of which was caught by the Japanese longline fishery (ICCAT, 2020). The catch total decreased sharply after this with declines in catches along the Brazilian coast. The number of catches increased to over 5,000 metric tons in the 1970s as the Japanese longline fleet expanded into the Gulf of Mexico and the northwest Atlantic (ICCAT, 2020). ICCAT imposed a catch limit in 1982 and this caused total catches to decline again. There was another decline in total catches in the mid-2000s to 1,638 tons in 2007. In recent years, the total catches have steadily increased, reaching 2,305 tons in 2019 (ICCAT, 2020). In the last 6 years, the total allowable catch (TAC) has not been exceeded in the West Atlantic, and this is likely due to the market and operation conditions and not species decline, according to ICCAT. Currently, the Western Atlantic population is not considered to be overfished; however, the biomass of the population has decreased by an estimated 11.7% from 2017-2020 (ICCAT, 2020).

To learn more about regulation and policy in the western Atlantic, the team contacted and interviewed Raymond Kane from the Cape Cod Fishermen’s Alliance. Kane has experience as a fisherman, a fisheries representative, and a lobbyist. He has been subject to regulations and has pushed for legislation regarding the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna fishery. It was found that he has extensive knowledge about the topic of this study. When asked about overfishing, Kane said that Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna are not being overfished. This claim is backed up by the Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS), which states in their advice to ICCAT that Atlantic Bluefin Tuna are not overfished as of 2020. One of the reasons for this, according to Kane, is the high regulations on the fishery by the United States. Currently, regulations in the Western Atlantic are based on recommendations from ICCAT (“Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.). In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) enforces these regulations.

There are several management measures and regulations in place. First, commercial and recreational fishermen must have a permit to harvest bluefin tuna (“Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.). Other measures include annual fishing quotas, gear restrictions, time and area closures, and minimum size limits (“Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.). Kane stated that current regulations mandate that tuna caught using rod and reel must measure at least 73 inches in length, while fish caught with harpoons must measure at least 81 inches. Another important regulation is that targeted fishing of bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Mexico, a spawning ground, is not allowed (“Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna,” n.d.).

A specific example of a successful management program is the Individual Bluefin Quota (IBQ) program. The program was designed to incentivize fishermen targeting other species, such as Atlantic Swordfish or Yellowfin Tuna, to avoid interactions with bluefin tuna (“New Requirements Protect Bluefin,” 2020). The program awards those who catch less bluefin tuna unintentionally with enhanced permissions to catch the fish that they desire. The program has had a substantial effect on the amount of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna bycatch. “Since it was implemented, the [IBQ] program has reduced the average annual bluefin bycatch by 65 percent compared to the three years before. That’s about 330,000 pounds—or around four fully loaded semi trucks—less bycatch each year” (“New Requirements Protect Bluefin,” 2020).

Recently, the Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna population count has stabilized as fewer tuna have been caught in recent years as shown in Figure 3 (ICCAT, 2020). It is likely that this is not only because of regulations. According to Raymond Kane, there was a collapse in the bluefin tuna market in 2003. He said that this had a substantial effect on the selling price of the fish. In the 1990s, Atlantic Bluefin Tuna were selling for around US $21 to $25 per pound, but now the same quality fish are selling for US $2 to $4 per pound. This, according to Kane, has made it impossible to make a living fishing for Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. The success of the fishery depends on the demand for the fish. Whether fishermen go fishing now depends on whether a person agrees to buy the fish, according to Kane. Low demand is bad for the fishermen and the economy but beneficial to Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna.

Eastern Atlantic Status and Regulations

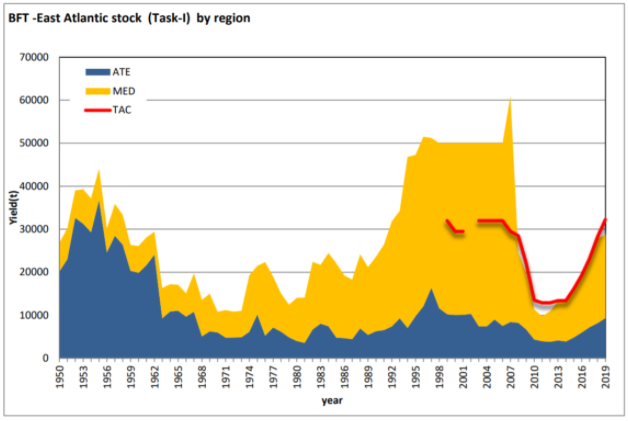

Eastern Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the past have been severely overfished. From 1996 through 2007, catches are said to have been vastly unreported; the predicted correct stock numbers were 50,000 to 61,000 metric tons per year over that 11-year span (ICCAT, 2020). Since then, regulations made by ICCAT have been put in place around the Mediterranean, reducing the average catches over the last five years to 23,093 tons per year (ICCAT, 2020). Figure 4 below visualizes the sharp decline in the tons of fish caught once normal regulations were adapted into stricter plans for recovery, which were first put in place in 2006 according to European fisheries expert, Neil Ansell. Once these recovery plans took action, the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna stock eventually reached a status where today it is no longer considered to be overfished.

Over the past few years, the stock has continued to improve; however, there is still more work to be done. In 2014, the implementation of stereo video cameras became part of regulation to help ensure that ICCAT was receiving true data that accurately represented how the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna was being fished. Unfortunately, there are still missing pieces for fully understanding how the population has changed since 2006 when recovery plans were put in place.

ICCAT’s 2006 recovery plan changed a multitude of aspects of the previous regulations to ensure recovery of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. The recovery plan enforced closed fishing seasons. This meant that fishing of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna was prohibited for different types of fishermen through different dates. Large long-line fishing vessels were prohibited from catching tuna from the start of June to the end of December. Purse seine fishing for Atlantic Bluefin Tuna was prohibited from the beginning of July to the end of December. The last type of fishing to be given a closed season was fishing by bait boat, which was prohibited for the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna from the 15th of November to the 15th of May (ICCAT, 2006). Having these specific closed fishing seasons helped the tuna reproduce and grow their population without being constantly fished.

Another change that helped the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna population increase was the increase of the minimum size of tuna that could be legally caught. This change prohibited the sale of tuna weighing less than thirty kilograms (ICCAT, 2006). Another part of the recovery plan was the implementation of a maximum percent bycatch for Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. Authorized fishing vessels were allowed a maximum of 8% bycatch of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna that weighed between ten and thirty kilograms (ICCAT, 2006). This allowed fishermen to make unavoidable mistakes without repercussions but worked to limit those mistakes.

The recovery plan also required all fishing vessels to keep a logbook to record the quantities of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna that were caught and kept on board the vessel. Information such as the date, time, and specific location of a catch was to be recorded in these logbooks. Communication and reporting of catches were also required by the recovery plan (ICCAT, 2006). This made sure that as few catches as possible would go unreported, which was important when it came to gathering data to adapt the plan for the future. There were numerous other rules that this recovery plan enforced, but those mentioned above were the most important and most relevant to our research.

To learn even more about regulation and policy in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Sea, the team contacted and interviewed Neil Ansell from the European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA). Ansell has been with the EFCA for seven years and holds a position as a fisheries consultant. In his time with the EFCA, Ansell has worked mostly with tuna fisheries control. He was able to share with the team information regarding how ICCAT enforces its regulations and policies in the Mediterranean Sea. Because each participating country has its own government, ICCAT provides regulation recommendations. The mode of enforcement is entirely up to each country’s own government, as long as regulations are in fact being enforced. In addition, the European Union, consisting of 27 countries, has to implement the rules and regulations as well. The most important information that we learned from Neil Ansell is that the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is no longer considered to be overfished in the Mediterranean Sea. As of 2019, ICCAT’s recovery plan has been changed to a management plan, which aims to maintain the now considered healthy Atlantic Bluefin Tuna population.

Black Market Trade

Because of the success of regulations across the Atlantic in recent years, overfishing is no longer a legal problem and has become an illegal problem, especially in the Mediterranean Sea. One example of a bluefin black market is the one that was suspended through Spanish Operation Tarantello in 2018 (European Union News, 2018). This illegal market was catching up to 2.5 million kg of tuna per year, which is double the estimated annual volume of the legal trade (European Union News, 2018). One of the reasons this market was so large is likely the amount of money it made. According to the article referenced previously, criminals earn at least €5 profit per kilogram of tuna. This means that the profit of this recently operating illegal market was approximately €12.5 million per year. With this information, it is evident that the potentially high value of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is a driver of illegal fishing.

Illegal markets are not only a danger to the bluefin tuna population but also to the health of consumers. In Operation Tarantello, for example, fish were stored and transported in unsanitary conditions, causing several cases of food poisoning (European Union News, 2018). Tuna were sometimes hidden underwater after being fished and were in cases transported in false bottoms under the decks of boats (European Union News, 2018). These unhygienic conditions caused the degradation of proteins in the tuna, making them harmful to consume (European Union News, 2018).

Another example of an illegal bluefin tuna black market is that run by Colonel Moammar Gadhafi in Libya until 2011 (Lewis, 2020). Prior to the fall of Col. Gadhafi, “…Libya operated a fleet of at least 48 purse seiners, which resulted in a hefty percentage of the entire Mediterranean bluefin tuna production being caught in Libyan waters” (Lewis, 2020). He was accountable to no one and this resulted in the massive exploitation of bluefin tuna. Eastern Bluefin Tuna were being caught in the Gulf of Sidra, which is a spawning ground and a marine sanctuary (Lewis, 2020). According to figures from ICCAT, 12,000 metric tons of bluefin tuna were being harvested annually, and that is only the amount declared to them (Lewis, 2020). For this reason, the fall of Col. Gadhafi is considered to be one of the reasons for the resurgence of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean in recent years (Lewis, 2020). Despite the fact that the population of Bluefin tuna is increasing, the task of management still remains for the future. Without proper management and cooperation, the black market could continue to be a problem and more people could start exploiting the Bluefin tuna in the future as their numbers increase.

Conclusion

The current global population of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna is in a state of recovery. Increasing populations in the east and west Atlantic indicate successful efforts made by ICCAT and the governments under its recommendation; however, in the western Atlantic, this could be a result of the changing Bluefin Tuna economy. Though the species is not fully recovered, current trends have brought the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna out of danger of extinction. While the species’ population has greatly recovered, there are still management regulations in place to maintain the population’s health. Unfortunately, the existence of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna black market trade still threatens the species as of this writing.

Methods similar to those protecting the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna can be used in other regions with other species in the future. The black market trade, however, demands heavier enforcement. It is recommended that governments impose greater punishments for vessels and operations found guilty of illegal fishing. More effective methods of monitoring water for illegal fishing should also be put into place. This may look like an increase in government patrol vessels or increased monitoring of ports for fish sales. At the consumer level, customers should look to identify where their tuna comes from to ensure that they avoid tuna from regions that may be at risk of overfishing. The Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna population is much more stable and healthy than the population of the Eastern Atlantic.

To expand on these findings, more research should be done on the behavior of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna in the west and the east. This research should focus on the interaction of individuals and possible cross-breeding of the two populations. More research should also be done on Atlantic Bluefin Tuna fishermen and their livelihoods to better understand policy regulation and overfishing as a whole from their perspective. Finally, more population data would assist officials in making decisions relating to the management of Atlantic Bluefin Tuna.

References

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://oceana.org/marine-life/ocean-fishes/atlantic-bluefin-tuna?utm_campaign=engage.

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Distribution Map. (n.d.). Smithsonian. Retrieved October 15, 2020, from https://ocean.si.edu/conservation/fishing/atlantic-bluefin-tuna-distribution-map

Bluefin Tuna. (n.d.).Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance. Retrieved October 16, 2020, from https://www.capecodfishermen.org/fisheries/bluefin-tuna

Bluefin Tuna. (n.d.). World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/bluefin-tuna

Gupta, A. (2017). There’s something fishy in the mediterranean: The harmful impact of overfishing on biodiversity. Duke Environmental Law & Policy Forum, 27(2), 317-344.

Hourston, J. (2019, Feb 19). Atlantic bluefin tuna: The forgotten superpredator. Retrieved from https://blueplanetsociety.org/2019/02/atlantic-bluefin-tuna-the-forgotten-superpredator/

How the illegal Bluefin tuna market made over EUR 12 million a year selling fish in Spain. (2018, October 17). European Union News. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A558624066/GPS?u=mlin_c_worpoly&sid=GPS&xid=d0f9baa7

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). (2006). Recommendation by ICCAT to Establish a Multi-annual Recovery Plan for Bluefin Tuna in the Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. Retrieved from https://www.iccat.int/Documents/Recs/compendiopdf-e/2006-05-e.pdf

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). (2020). SCRS Advice to the Commission. Madrid, Spain: Author. Retrieved from https://iccat.int/Documents/SCRS/SCRS_2020_Advice_ENG.pdf

International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). (n.d.). Recent Publications. Retrieved from https://www.iccat.int/en/

Lewis, D. (2020, November-December). BLUEFIN IN MOTION: Stocks show favorable rebound in Europe. Marlin, 39(7), 34+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A640620370/GPS?u=mlin_c_worpoly&sid=GPS&xid=8de5342d

National Geographic. (2018, September 21). Atlantic Bluefin Tuna: National Geographic. Animals. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/a/atlantic-bluefin-tuna/.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (n.d.). Western Atlantic Bluefin Tuna. Retrieved from https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/western-atlantic-bluefin-tuna

Taylor, N. G., McAllister, M. K., Lawson, G. L., Carruthers, T., & Block, B. A. (2011, December 9). Atlantic Bluefin Tuna: A Novel Multistock Spatial Model for Assessing Population Biomass. Retrieved December 05, 2020, from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0027693

The Pew Charitable Trusts. (2020, October 6). A Global Tuna Valuation: Netting Billions 2020. Netting Billions 2020 A Global Tuna Valuation. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/10/netting-billions-2020-a-global-tuna-valuation.

A class, kind, or group marked by common characteristics or by one common characteristic.

A protein inside red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to tissues and organs in the body and carries carbon dioxide back to the lungs.

The value of fish sold from fishermen at docks to market representatives (The Pew Charitable Fund)

The value of fish sold from markets to consumers (The Pew Charitable Fund)

An individual [fishing] quota (IQ or IFQ) is an allocation to an individual (a person or a legal entity (e.g., a company)) of a right [privilege] to harvest a certain amount of fish in a certain period of time. It is also often expressed as an individual share of an aggregate quota, or total allowable catch (TAC). (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)

A trophic cascade where the top consumer/predator controls the primary consumer population, so the primary producer population thrives.

type of fishing in which long line with several baited hooks is dragged behind a boat (Marine Stewardship Council)

A large wall of netting deployed around an entire area or school of fish.

A fishing operation in which bait is caught through purse seine and then used to attract targeted fish. The bait is thrown in the water, where it hides in the shadow of the boat. Water is sprayed onto the ocean’s surface to simulate small splashing fish. Numerous fishing rods are lined up on one side of a boat and lowered into the disturbed water for catching the targeted fish. (ICCAT)

body of water on the north coast of Libya (Wikipedia)