18

Ryan Polansky, Kathryn Rodriguez, Neilie Fromhein, and Jeffrey Compere

Introduction

The goliath grouper, Epinephelus itajara, is a long-lived large-bodied fish found within warmer Atlantic waters (Koenig et al. 2019). Like much of the grouper species, goliath groupers are protogynous hermaphrodites, meaning they initially mature as females and later as males (Koenig et al. 2019). This, combined with their lifespan and predictable mating routines left the grouper vulnerable to overfishing, leading to their near extinction in the 1990’s. While currently protected by a fishing moratorium, there has been recent pushback from fisheries hoping to yet again fish the still-vulnerable species. We hope to address misconceptions and establish the benefits of continued conservation.

Species Introduction

The goliath grouper is the Atlantic’s largest grouper, and when mature, can grow up to 800 pounds in weight and 8 feet in length (Fisheries NOAA n.d.). They are relatively long-lived, given that the maximum recorded age of a goliath grouper is 37 years old; however, scientists have predicted that they have the ability to live to the range of 50-100 years (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission n.d.). Adults typically are a mottled brown-yellow or green-grey color with spots or faint vertical bars. Younger groupers exhibit similar coloration but are often more muted. Characteristic features that allow them to be distinguished from other large-bodied grouper species are their broad head, rounded tail, short dorsal spine, and small eyes (Robins 2021). Additionally, the grouper has between three and five rows of teeth, including short underdeveloped canine teeth, allowing it to be distinguished from other Atlantic grouper species. While this can make the grouper appear more dangerous to undereducated fishers and divers, the grouper is an ambush predator that primarily feeds on crabs and other slow-moving fish species, which humans are not. It captures prey by expanding its mouth and sucking in the prey whole, meaning that its actual bite is weak, and wouldn’t pose a danger to humans (Robins 2021). Some of its natural predators include barracudas, king mackerel and moray eels, and Sandbar sharks; however, its populations are mainly threatened by fishing and habitat destruction.

The goliath grouper has been found in the Gulf of Mexico, off the coast of Florida, in the South Atlantic, off the coast of Africa, and as far north as New England (Fisheries NOAA n.d.; Figure 1). Its primary habitat, as one of the only groupers to inhabit brackish water, is shallow, only as deep as 46 meters, and consists mainly of coral, rock, and mud bottoms (Robins 2021). Young goliath groupers live in mangrove habitats, most commonly off southwest Florida, and move to shallow reefs as they grow. The destruction of mangrove habitats is another contributing factor to species vulnerability, which will be explored later. Adults are usually solitary when they’re not forming aggregates during mating season and remaining in the same area for large periods of time (Robins 2021). During mating season, aggregates form primarily around shipwrecks, isolated reefs, and rock ledges as these are spawning sites. In order to form these aggregates, they use a specialized bladder to create rumbling sounds with which to locate other members of their species. Groupers are known to be nocturnal spawners, preferring to spawn under the new moon, meaning that aggregates normally form at night or during the early morning hours (Koenig et al. 2019). Aggregates have been recorded to involve around 10 groupers in the past, however, due to successful conservation efforts over the last 30 years, aggregates of the species often see groups of 20-40. Once the eggs are fertilized, they are distributed by ocean currents, resulting in spawning during the late summer months, July-September (Fisheries NOAA n.d.).

Figure 1. Range map of the goliath grouper. “World distribution map for the goliath grouper” by RH Robins, Florida Museum, with permission

Goliath groupers generally do not exhibit sexual dimorphism as they are protogynous hermaphrodites; they spend the first 1-6 years of their lives begin females and eventually mature into males. The males often have a much slower growth rate. Groupers in the transitional state are hard to find, however, the notion of protogynous hermaphrodism is supported by similarities to other species of groupers. In a study executed by SEDAR (SouthEast Data, Assessment, and Review) the sex ratio was seen as 1:1; however, later in the article, they concluded that more long term monitoring was needed to draw conclusions as to life traits such as reproductive habits, gender ration, and sexual maturity, as well as more studies are needed to understand genetic variation (SEDAR 2011, SEDAR 2016). This lack of data and general knowledge of the species is largely due to the fishing moratorium on goliath groupers, as there is little to no data being brought in by fishers in the Atlantic.

Current Species Management

Due to its long lifespan, late sexual development, slow maturity, protogyny, and spatially predictable mating routine, the goliath grouper is exceptionally vulnerable to overfishing. As the fish is incredibly large it was often sought after by anglers looking to fish for sport and trophies or by fishing companies for a perceived value in its large amounts of flesh. From the 1970’s to the 1980’s the goliath grouper was fished to near extinction in US waters, as a culmination of half a century of overfishing (Koenig et al. 2019) (McClenachan 2009). In 1990 goliath groupers were placed under federal and state fishing bans closing them to harvesting and possession within the United States. Many of these bans are still in place today (SAFMC 2021). Later in 1991 the species was listed as part of the Endangered Species Act and labeled as a species of concern; this label has since been removed in 2006, but the fishing bans still remain in place by fishery management councils (Fisheries NOAA n.d.). It was expected for the species to have high enough populations to be fished again by the mid 2000’s, however, in 2004 it was concluded by SEDAR that populations would not reach their targets until 2020 or later. A secondary petition to get the grouper listed as endangered or threatened was filed in 2011; however, it was concluded that there was not enough scientific or commercial data to once again put the species under review (Barnett et al. 2011).

The current Policy within US waters is if the goliath grouper is caught it must be returned to open waters unharmed and alive. Smaller goliath grouper can be removed from the water to remove the hook properly however large goliath grouper should not be removed from the water due to the fact that their skeletal structure can not adequately support their weight without causing internal damages. As such fishers that fish within the areas populated by goliath groupers should be prepared to release larger fish by cutting the lines rather than pulling them out of the water and should be prepared adequately to do so (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission n.d.). These conservation efforts have been successful with the current population increasing year by year. The increased abundance of goliath grouper is noticed in Tampa Bay, Charlotte Harbor, and the Ten Thousand Islands. Increasing perceived abundance in these areas and among fishermen is encouraging, however, the species remains incredibly at risk.

Other countries within the goliath grouper’s range have not instituted enough measures to fully protect the species. In Mexico, there is little to no policy on the fishing of goliath groupers, especially in the southeast where US and Gulf of Mexico protections are no longer in effect. This general lack of regulation has put the grouper species even more at risk (Aguilar-Perera et al. 2009). Additionally, there have been instances of poaching off the coast of Brazil, even though a fishing moratorium has been instituted there since 2002, nine years after the ban was placed over US and Caribbean waters. This increased poaching has been due to limited enforcement of the moratorium which was granted the ability to stay in place until 2023. A small subsection of the grouper also lives to the west coast of Africa where there is no legislation passed to currently protect the species. These populations are generally less in danger, as they are mostly caught by local spearfishers rather than members of the fishing industry or for sport (Bertoncini et al. 2018).

The main targets for conservation in these areas are the spawning aggregates as they are easy targets for poachers, and any tampering with the sites can cause drastic effects on resulting grouper populations. A recent study concluded that even though these management systems are imperfect they are incredibly necessary as the loss of these systems would cause an estimated population decline of 85% in just under 2 generations (Bueno et al. 2016).

Threats to the Species

As mentioned previously, the threat of overfishing is obviously very real and imminent to the species, however, there are some other threats that also bear being addressed. These threats include loss of mangrove coverage, red tides, cold temperature events, and increasing mercury levels (Bertoncini et al. 2018). These elements of different threats to the populations also do not act alone as humans, ever a part of the ecosphere, continue to present increasing negative pressures on the species.

Mangroves provide an important location for the development of juvenile goliath groupers. This is especially important as the grouper has such a long development time. Their time spent within the mangroves is determined by the amount of dissolved oxygen and salinity of the waters and normally last around 6 years. The mangroves are necessary for maintaining very specific conditions necessary to the development of the juvenile groupers (Bertoncini et al. 2018). This developmental phase is crucial to the accumulation of goliath grouper biomass and as such the destruction of these habitats presents an imminent threat to the long-lived slow-developing species. Mangrove habitats have seen a reduction by at least a third since the 1990’s, relatively similar to the population decline of the grouper themselves. Humans have also created some anthropogenic factors that make this habitat largely unsuitable for the juvenile groupers as well as additional challenges caused by eutrophication.

Algal blooms are often preceded by the eutrophication of an ecosystem. A particularly devastating example of a large-scale algal bloom is the red tide (Bertoncini et al. 2018). This bloom is comprised of Karenia Brevis, a dinoflagellate that produces toxins that are harmful to developing juvenile goliath groupers especially as it continues to be a problem in the southeast of Florida. 2018 presented another red tide year to challenge south Florida’s ecosystems, and the extent of the damage caused by that bloom has not yet fully been interpreted in regards to goliath grouper populations (Koenig et al. 2019).

Juvenile goliath groupers also saw a very large population in 2008 within Florida waters as there was an extreme cold time event. Groupers being a tropical species, especially as juveniles are highly susceptible to be impacted by cold weather patterns. The cold event that occurred in 2008 caused a juvenile goliath grouper population reduction of around 90% (SEDAR 2016) and recovery efforts still have not been able to confirm if the species has yet recovered from that one event. These cold time events, much like the red tide events are rare, but due to human interference in different forms have become more prominent in recent years, causing extreme setbacks in the recovery of the grouper species (Koenig et al. 2019).

While the high mercury content found within goliath grouper species may at first seem beneficial as it may have the effect of dissuading potential fishers, the mercury has also had potential negative effects on the fish themselves. As mercury is a toxin that occurs with bioaccumulation, while the effects of eating the grouper may be lethal to humans, there are several sub-lethal effects that may cause groupers to be less fit for their environment. These effects are lesions, decreased immune response, reduced liver capabilities, and problems maintaining osmolarity (Koenig et al. 2019). While these effects will not directly cause a population decline they have several implications to reproductive viability where they could negatively affect groupers longevity as a species the most, as female egg viability may be compromised (Bertoncini et al. 2018). All of the aforementioned factors do largely impact the grouper’s recovery, however potentially the most threatening upcoming challenge for the grouper is once again people’s ignorance.

There has been a recent push for the re-legalization of goliath grouper fishing, for reasons including documentation of their biology, reducing their “strain” on more lucrative fish populations, and making humans safer — beliefs that are not supported by facts. People are, in many cases, undereducated about goliath groupers, which leads to them forming incorrect opinions. Despite having been overfished to near extinction starting in the 1800’s, the species has been placed into a role as a scapegoat. Fishers have blamed groupers for recent setbacks in the fishing industry and goliath groupers have been characterized as nuisances and harmful creatures to both humans and the environment (Koenig et al. 2019). The Goliath grouper is also known culturally as a “bottom-fish” because of its wide variety of prey it feeds on. However, this mischaracterization has been harmful to the species because fisheries use it as justification to continue hunting it. In reality, there are almost no benefits to the fishing of groupers due to their high mercury content, positive impacts on biodiversity, and large body size. Their large body size has, in the past, contributed to both them being overfished and the perceived danger that they may cause. However, they have almost no fear towards humans, making them rather benign, but also makes them ideal targets for spearfishers. Due to their lack of fear, they are often regarded as “gentle-giants” by knowledgeable divers and fish enthusiasts. (US Department of Commerce NOAA 2011). Even so, this pushback still exists and it’s been estimated that due to their slow growth rates, hunting a hundred of them annually for four years would have drastic negative consequences on their breeding population.

Species Value

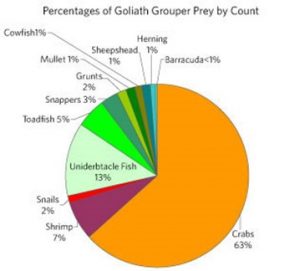

Goliath groupers are a large and important predator in the reef ecosystem, as well as the other ecosystems that they inhabit. There have been noted positive correlations between grouper biomass and biodiversity exhibited within coral reef ecosystems overall, however, the mechanism and the actual cause of this correlation remain unknown. They feed on a diversity of fishes and invertebrates and also provide a good food source for barracudas and reef sharks (JohnC 2018; Figure 2). Furthermore, as a result of their size and hunting habits, they actively increase the complexity and habitability of their native ecosystems by clearing mud and silt, allowing other species to flourish to a greater extent than before. Figure 2. Prey items eaten by goliath grouper. “Pie diagram showing main prey items of goliath grouper diet, adult and juveniles combined” by Koenig and Colemna, NOAA MARFIN Project Final Report, Public Domain

Figure 2. Prey items eaten by goliath grouper. “Pie diagram showing main prey items of goliath grouper diet, adult and juveniles combined” by Koenig and Colemna, NOAA MARFIN Project Final Report, Public Domain

The goliath grouper also represents a potential biocontrol for the invasive lionfish. The majority of disrupted and invaded coral reef ecosystems targeted by lionfish are in the Caribbean, an overlapping range with goliath groupers. While natural biocontrols for lionfish are generally poorly studied, they have previously been found in the stomachs of large-bodied groupers, the goliath grouper is the most common representative. These observations were the basis for a revolutionary study in 2011, that investigated two protected areas for groupers. In looking at these two locations, researchers found that there was a statistically significant negative correlation between grouper biomass and lionfish biomass. This correlation indicates that some form of biocontrol was occurring and can continue to occur between these species. The mechanism for this biocontrol is most likely predatory due to lionfish having been found present in groupers’ stomachs and the lack of competitive overlap in the two species’ resources like food (Mumby et al. 2011).

Similar to the positive correlation between goliath grouper biomass and reef biodiversity, there is also a positive correlation between goliath grouper populations and an increase in the capture of other fish (Koenig et al. 2019). While the complete nature of this relationship is not yet known, it is likely that any negative impacts to goliath grouper populations would also affect this trend and by extension the seafood industry. While there is a lot of pressure from anglers and fishermen to open up goliath grouper fishing at least recreationally, the price of goliath groupers would only be around $34-79 USD, an amount that is almost negligible (Shideler and Pierce 2016). Goliath groupers, unlike these other reef fish, are quite difficult to commercialize due to their large body size and lack of consumable meat products. Based on these factors many knowledgeable fishermen have decided that it is not worth the risk of breaking the fishing moratorium (Gerhardinger et al. 2006).

The vast majority of economic benefits that can be developed from the grouper species do not lie in fishing but rather in the protection of the species. Ecotourism presents a great opportunity for economic profit from the goliath grouper, oftentimes in the form of paid diving trips. This boost to the tourist industry can also help to advocate for the grouper’s continued conservations, as demand to go to their spawning aggregates has increased since populations returning to the sites have increased, experienced divers, being willing to pay upwards of 200 USD for a single experience (Shideler and Pierce 2016). This data shows that the Goliath grouper has very high economic value with regard to the tourism industry. The money generated from this could be funneled into education and more conservation projects, as an economic incentive to keep the spawning sites as healthy as possible has been created.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the goliath grouper provides many benefits to its biosphere. In order to maintain those benefits, more conservation efforts must be enacted by countries and organizations set on protecting the goliath grouper. Ways this can be done is by educating fisheries on the positive aspects of conserving goliath grouper. This would benefit conservation efforts because many fisheries have called for the calling of goliath groupers in the past several years. Which would drastically harm their numbers and recovery. A policy that needs to be enforced is the ban on net fishing in goliath grouper waters. The benefit of this would be promoting ecotourism that could spread awareness of the species and generate money for continued conservation efforts. If the goliath grouper is caught accidentally the policy is to release it back into the water unharmed and in the location it was caught to ensure its safety (Fisheries NOAA. n.d.). To learn more about the goliath grouper or to donate to conservation efforts go to https://oceana.org/marine-life/ocean-fishes/atlantic-goliath-grouper.

References

Aguilar-Perera A, González-Salas C, Tuz-Sulub A, Villegas-Hernández H. 2009. Fishery of the Goliath grouper, Epinephelus itajara (Teleostei: Epinephelidae) based on local ecological knowledge and fishery records in Yucatan, Mexico. Revista de Biologica Tropical 57(3): 557–566. https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v57i3.5475

Barnette M, Manning L. 2011 1 June. Endangered and threatened wildlife; Notice of 90-day finding on a petition to list goliath grouper as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Federal Register 76(105). [accessed 2021 Mar 4]. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2011-06-01/pdf/2011-13549.pdf

Bertoncini AA, Aguilar-Perera A, Barreiros J, Craig MT, Ferreira B, Koenig C. 2018. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T195409A145206345. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T195409A145206345.en.

Bueno LS, Bertoncini AA, Koenig CC, Coleman FC, Freitas MO, Leite JR, De Souza TF, Hostim-Silva M. 2016. Evidence for spawning aggregations of the endangered Atlantic goliath grouper Epinephelus itajara in southern Brazil. Journal of Fish Biology 89(1):876–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.13028

Coleman FC. n.d. Goliath grouper back from the edge. Coleman Lab, Marine Ecology and Conservation FSUCML. [accessed 2021 Mar 8]. https://marinelab.fsu.edu/labs/coleman/research/grouper-ecology/goliath-grouper-lead-page/goliath-back-from-the-brink/

Coleman FC. n.d. Vulnerability of the goliath grouper population in Florida. Coleman Lab, Marine Ecology and Conservation FSUCML. [accessed 2021 Mar 1]. https://marinelab.fsu.edu/labs/coleman/research/grouper-ecology /goliath-grouper-lead-page/vulnerability/

Fisheries NOAA. n.d. Atlantic Goliath Grouper. NOAA. [accessed 2021 Feb 25]. https://www .fisheries.noaa.gov/species/atlantic-goliath-grouper

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. n.d. Goliath Grouper. Myfwc.com. [accessed 2021 Mar 4] https://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/goliath/

Gerhardinger LC, Marenzi RC, Bertoncini ÁA, Medeiros RP, Hostim-Silva M. 2006. Local ecological knowledge on the goliath grouper epinephelus itajara (teleostei: serranidae) in southern Brazil. Neotropical Ichthyology, 4(4), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252006000400008

JohnC. 2018 March 6. Goliath grouper. Petworlds.net. [accessed 2021 Mar 8]. https://www.petworlds.net/goliath-grouper/\

Johnson A. 2017 September 15. Marine Conservation Institute takes a stand to support the Atlantic Goliath Grouper. Marine Conservation Institute. [accessed 2021 Mar 4]. https://marine-conservation.org/on-the-tide/atlantic-goliath-grouper/

Koenig CC, Coleman FC, Malinowski CR. 2019. Atlantic goliath grouper of Florida: To fish or not to fish. Fisheries 45(1): 20-32. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsh.10349

Koenig CC, Coleman FC, Kingon K. 2011. Pattern of recovery of the goliath grouper Epinephelus itajara population in the sSoutheastern US. Bulletin of Marine Science, 87(4), 891–911. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2010.1056

McClenachan L. 2009. Historical declines of goliath grouper populations in South Florida, USA. Endangered Species Research 7: 175-181. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00167

Mumby P, Harborne AR, Brumbaugh DR, Gratwicke B. 2011. Grouper as a natural biocontrol of invasive lionfish. PloS One, 6(6), e21510–e21510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021510

Oceana. n.d. Atlantic Goliath Grouper. Oceana.org [accessed 2021 Mar 8]. https://oceana.org/marine-life/ocean-fishes/atlantic-goliath-grouper

Robins RH. 2021. Goliath grouper Epinephelus itajara. Florida Museum [accessed 2021 Mar 8]. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/epinephelus-itajara/

SAFMC (South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council). 2021. Goliath Grouper Regulations. [accessed 2021 Mar 1]. https://safmc.net/regulations/regulations-by-species/goliath-grouper/SEDAR 47

SEDAR (SouthEast Data, Assessment, and Review). 2016. SEDAR 47 Stock Assessment Report. [accessed 2021 Mar 4]. http://sedarweb.org/docs/sar/S47_Final_SAR.pdf

SEDAR (SouthEast Data, Assessment, and Review). 2011. SEDAR 23 Stock Assessment Report. [accessed 2021 Mar 11]. http://sedarweb.org/docs/sar/S23_SAR_complete_and_final.pdf

Shideler GS, Pierce B. 2016. Recreational diver willingness to pay for goliath grouper encounters during the months of their spawning aggregation off eastern Florida, USA. Ocean & Coastal Management 129: 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.05.002

US Department of Commerce NOAA. Gentle giants: Goliath grouper. Ocean Today. 2011 Jul 5 [accessed 2021 Mar 11]. https://oceantoday.noaa.gov/gentlegiants_goliathgrouper/

Animals that are born as female and eventually develop as males.

Water that has a salinity higher than that of freshwater, but lower than salt water

difference in appearance between males and females of the same species

mass of an organism in a given space or volume

When a body of water becomes over enriched with minerals and nutrients, causing an increase in algae. This can result in and increase in animal death due to oxygen depletion

The variety of life in the world or in a particular habitat or ecosystem.

method of controlling the population of a species that is regarded as a "pest"

A type of tourism that allows for people to safely observe exotic wildlife and support conservation efforts.