2

Robert Belmonte, Sol Giesso, Alana Lue Chee Lip, and Mikayla Raffin

Abstract

Panthera onca is the largest feline in the Americas. They are apex predators that feed opportunistically on a wide variety of prey and thus regulate their ecosystem from the top-down. Historically, they have been found in areas stretching from the southern United States to Argentina, but their range is now concentrated in Central and South America due to habitat loss. Humans are a major threat to jaguars being responsible for habitat loss, poaching, and retaliatory killings. Given the jaguar’s ecological, cultural, and economic significance, conservation efforts need to be implemented by many countries to help preserve jaguar populations.

Figure 1: The jaguar (Panthera onca) and its physical appearance. “Jaguar at Chester Zoo“ by Steve Wilson, CC BY 2.0.

Figure 1: The jaguar (Panthera onca) and its physical appearance. “Jaguar at Chester Zoo“ by Steve Wilson, CC BY 2.0.

The jaguar (Panthera onca) is the largest cat in the Americas, measuring five to six feet long (not including its tail) and weighing up to 250 pounds (about 113 kg). Males are usually slightly larger than females in both size and weight (Law et al. 2020). As such big creatures, jaguars are apex predators, meaning that they prey on many different species within their habitat without being preyed upon themselves. Their lifespan ranges between twelve and fifteen years in the wild, around the same as most large felines (Law et al. 2020). Their coats are pale yellow with rosettes, similar to the coat of a leopard, as shown in Figure 1.

Jaguars live mostly in Central and South America, with their habitats ranging as far north as Mexico and the southern United States, and as far south as Argentina (Quigley et al. 2017). They can live in various habitats including mountainous areas, jungles, and grasslands, but they primarily live in dense forests near water. Vegetation is particularly important for their hunting style, in which they rely on surprising the prey in proximity rather than chasing them. They tend to avoid arid and dry climates as they need water for temperature control and food (Crawshaw and Quigley 1991). By the turn of the 20th century, jaguars had a geographic range of approximately 19,000,000 km2, but this range is a reduction of over 50% from their estimated range in 1900 (Sanderson et al. 2002).

Given that the jaguar has inhabited the Americas since it evolved about two million years ago (Law et al. 2020), it has been the subject of many myths and indigenous beliefs. One old Mayan legend tells the story of the mighty jaguar’s origins, and it goes like this:

Many years ago, in the rainforest of the Mayan World, all animals were great friends; the deer, the curassow, the peccary, the crocodile, and the monkey treated each other with respect and did not prey on each other, instead feeding on herbs, fruits, and seeds.

The most admired animal was the jaguar, who had no spots at the time. His blonde skin glowed and he would often approach the water to see his reflection. “No one has skin as perfect as mine,” he would say, boastfully.

One day, some monkeys found an avocado tree and started eating the fruits that had fallen and throwing them at each other. The jaguar got close to the monkeys, and one of them jokingly threw an avocado at him, staining his back. They all started laughing, but the jaguar felt humiliated and enraged. He captured the monkey and took him to his cave to eat. The rest of the animals escaped, horrified.

Nearby lived Yum Kaax, the god of vegetation and guardian of the animals. The monkeys explained what had happened and asked for help. Yum Kaax responded, “We will give this arrogant animal a lesson,” and sent the piccaries to help.

The next morning, the strongest peccaries arrived at the jaguar’s cave and led him to the black sapote tree, where the monkeys awaited. They threw the tree’s fruits at the jaguar, staining his entire coat. The feline escaped to wash himself, but the spots would not come off – they were magic ones from Yum Kaax.

The jaguar roared and threatened the others: “From now on you are my enemies, and I will never leave you alone!” For some time, the monkeys and the peccaries were captured by the jaguar with ease. Yum Kaax realized they were at a disadvantage, so he gave the monkeys long tails so they could climb up high and the peccaries thicker skin and sharp fangs.

Now the monkeys do not come down from the trees often; they learned to live almost entirely on them. When the jaguar starts climbing a tree, the monkeys yell and flee. The peccaries remained on the land, but when the jaguars approach, they huddle up and defend themselves with courage.

The jaguar now needs to work harder to catch its prey. He learned not to be narcissistic and to live hidden within the vegetation. Only like this he can surprise his prey.

Regardless, the jaguar was still feared and admired, not only by the animals but also by the Mayans, to whom it symbolized power and fierceness.

As a top predator, the jaguar is an opportunistic, generalist carnivore, so its prey ranges from capybaras, deer, and armadillos to tortoises, livestock, and fish (WWF 2020). They typically kill by attacking with a deep bite (Figure 2) to the neck that suffocates the prey, although they have more specific techniques for certain animals. For instance, they use their paws to scoop out the meat from a turtle or a porcupine’s body, whereas to hunt crocodiles they paralyze them with a bite (Law et al. 2020). To some, it may sound strange that jaguars hunt aquatic prey, such as turtles and fish, since cats are commonly thought to be averse to water, but the jaguar is actually an avid swimmer and diver and likes to spend time near water.

Figure 2: Photograph of a jaguar’s deadly jaw and fangs. Photo by Arcaion, Pixabay license.

Figure 2: Photograph of a jaguar’s deadly jaw and fangs. Photo by Arcaion, Pixabay license.

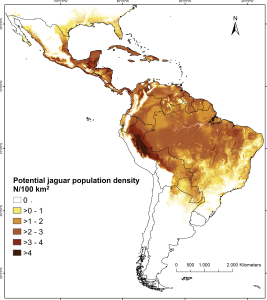

Jaguars tend to hunt alone since they are territorial (Garcia Fontes et al. 2021), but they have occasionally been observed hunting in pairs as young siblings (Law et al. 2020) or when they form temporary pairs during mating periods (SDZGL 2020). They are nocturnal and spend the majority of their time resting and hiding so they can ambush their prey, with little time in transit (Crawshaw and Quigley 1991). Their coat pattern aids this method of hunting as it allows them to blend in with the dappled shadows on the forest floor. Furthermore, food is not a limiting factor for jaguars since they are generalists, so they are not regulated from the bottom-up in their natural habitats. Instead, their low population density (shown in Figure 3) is mostly determined by their own territoriality (de Azevedo and Murray 2007). The fact that they are rarely regulated from the bottom-up is particularly important because it means that they are less threatened by the extinction of prey species that may be more susceptible to human impacts. Instead, jaguars regulate the ecosystem through top-down regulation.

Figure 3: Potential population density of jaguars in Central and South America. “Predicted spatial variation of jaguar potential densities across North and South America” from Jędrzejewski et al. (2018), CC BY 4.0.

Since they strongly influence the populations of other species (especially those in lower trophic levels) in the region through this top-down regulation (de Azevedo and Murray 2007), the jaguar is regarded as a keystone species. A study found that around 60% of the mortality of jaguars’ prey species is due to predation by jaguars, and 91% of the predation incidents in the area were carried out by jaguars (de Azevedo and Murray 2007). However, since the jaguar often prefers larger species, they sometimes consume them indiscriminately, which can lead to drastic decreases in the prey’s population size and ultimately result in destabilization of the ecosystem (de Azevedo and Murray 2007).

Although the jaguar may appear to be a fierce, cruel creature with regards to its prey, it is equally as terrorized by humans. The main threats facing Panthera onca are habitat loss and fragmentation, killing for trophies, illegal trade of body parts, retaliatory killings associated with livestock depredation, and competition with human hunters for wild meat.

High deforestation rates in South America related to soy, palm oil, and cattle ranching contribute to habitat loss and fragmentation. As the jaguar’s habitat is invaded by humans for agriculture, its native prey is displaced. As a result, jaguars resort to hunting cattle, but this often leads to them being killed in retaliation by angry farmers. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the demand for wild meat (much of which includes jaguars’ prey items) increases with the increasing population of Latin American countries (Quigley et al. 2017).

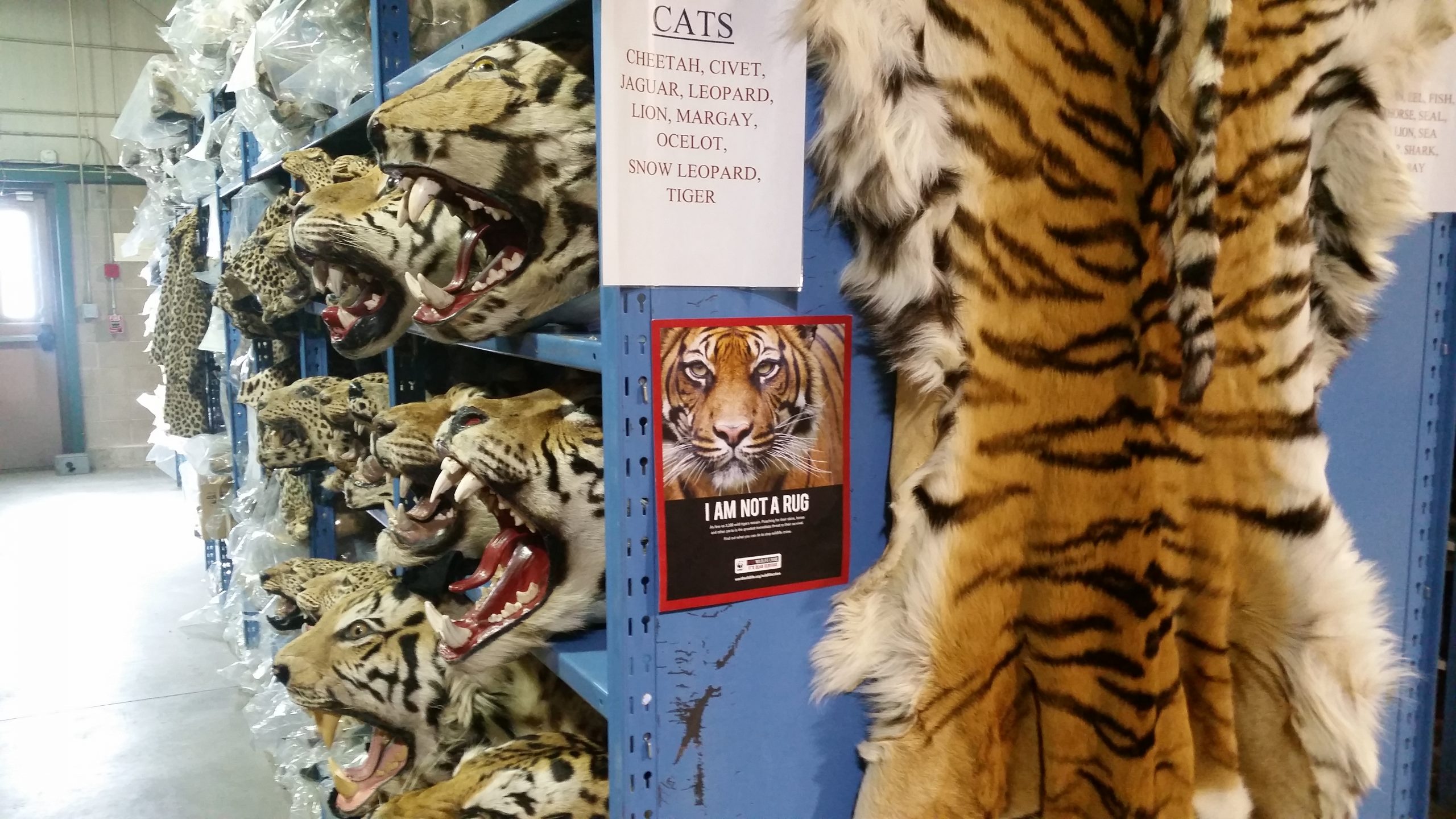

Another major threat to jaguars is illegal trafficking, where poachers sell their furs, teeth, skins, and claws as clothing or jewelry (Arias et al. 2020), as illustrated by Figures 4 and 5. Although commercial hunting for jaguar fur has drastically declined since the mid-1970s, the demand for their paws, teeth, and other parts remains (Quigley et al. 2017). Since most jaguar trafficking occurs locally and is not highly organized, it is difficult for governments to regulate it. This matter is made even more complicated by the fact that their range includes many different countries, each of which has its own unique laws against poaching.

Figure 4: Photograph depicting the illegal wildlife trade of large felines, including the jaguar. “Illegal Wildlife Property” by Ryan Moehring, USFWS, CC BY 2.0.

Figure 4: Photograph depicting the illegal wildlife trade of large felines, including the jaguar. “Illegal Wildlife Property” by Ryan Moehring, USFWS, CC BY 2.0.

Figure 5: Exhibit in the South American collection of the American Museum of Natural History, Manhattan, New York City, New York, USA of a necklace featuring jaguar teeth. “Necklace, jaguar teeth on palm fiber cord, Tucano people – South American objects in the American Museum of Natural History” by Daderot, CC0 1.0

.

The remaining jaguar population size is very difficult to determine because of their secretive nature and low-density distribution. Their population density varies (as previously shown in Figure 2), but the jaguar is found more commonly in areas with less human interaction (Quigley et al. 2017) farther away from cities and human development. Most estimates of population size range between 64,000 (Quigley et al. 2017) and 173,000 individuals (Jędrzejewski et al. 2018)—an unusually disparate range for such large mammals. Because of this, it is difficult to gauge how extensive and detrimental the human impact on jaguars truly is. There is typically about a 1:1 ratio of male and female jaguars both in the wild and in captivity (Baker et al. 2002), so chances of reproduction are not often a limiting factor in large subpopulations, although the number of cubs one mother can support at one time can be limiting.

It is during reproductive periods that jaguars break some of their normal behavioral patterns. Female jaguars roam widely throughout their habitat during estrus (a 6-17 day period) to advertise that they are receptive to mating (CSCOZ 2020) and increase their chances of finding a mate. Males and females form temporary pairs, traveling and feeding together until they separate after copulation (SDZGL 2020), as males sometimes kill and eat the cubs (Law et al. 2020). Since females go into estrus every 47 days, reproduction and births can occur year-round (SDZGL 2020), but births in temperate regions are often concentrated in the summer when food is most abundant (CSCOZ 2020) since mothers need to find enough large ungulate prey to feed their cubs. Gestation lasts 100 days and litters contain 2-4 cubs (shown in Figure 6), which are completely dependent on their mother for the first year of life (SDZGL 2020). By two years old, the juveniles are finally independent of their mother and go on to reach sexual maturity by the age of four (SDZGL 2020).

Figure 6: Photograph of a jaguar mother in captivity and her newborn cub. “Mother jaguar and cub” by Jim Bauer, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Figure 6: Photograph of a jaguar mother in captivity and her newborn cub. “Mother jaguar and cub” by Jim Bauer, CC BY-ND 2.0.

Given their small litter size and the cubs’ extended dependence on their mother, along with habitat loss and other human threats, the overall status of the Panthera onca is near threatened according to the IUCN Red List. However, this designation varies across different regions and subpopulations (Quigley et al. 2017). For instance, populations in 70% of its range have a high probability of survival, while those in 18% of its range have a medium probability of survival and those in 12% of its range have a low probability of survival (Quigley et al. 2017).

The jaguar has already become extirpated from El Salvador, Uruguay, and largely the United States. It is also suspected that the jaguar population has declined by 20-25% over the past three generations, and their range has decreased by 20% between 2002 and 2015 (Quigley et al. 2017). However, these numbers could be significantly underestimated due to their secretive and solitary nature. Connectivity between populations has also declined, leading to more frequent extirpations and loss of genetic diversity. Moreover, these increasingly isolated groups have smaller populations and fewer chances for reproduction. Out of the 34 different subpopulations of jaguars that live in Central and South America, 73% of them met the IUCN Red List‘s criteria for being critically endangered. The largest subpopulation, which lives in the Amazon rainforest and hosts 89% of all individuals, was considered to be Least Concern (Quigley et al. 2017), but this could change quickly as habitat loss continues.

The loss of jaguar populations has adverse effects on the environment, as well as on human society and the economy. In terms of the environment, the loss of large carnivore species such as the jaguar leads to trophic cascades, due to the previously discussed top-down regulation afforded by such species. This trophic cascade involves dramatic changes in the population numbers of species in lower trophic levels (Estes et al. 2011), as well as changes in the abiotic environment. For instance, if the jaguar were to go extinct, herbivore populations would increase. This would then lead to increased feeding upon the area’s vegetation, and would ultimately result in a decrease in plant abundance and possible changes in the distribution of plant species. Furthermore, a change in plant species distribution could change factors such as the ratio of carbon to nitrogen in the soil, which could then lead to further changes in the ecosystem (Ripple et al. 2014). On the other hand, if jaguars ate too many herbivores, producer density would largely increase and this increased competition between plant species may also lead to changes in their distribution.

In addition to this regulation of the environment, jaguars are also regarded as umbrella species, meaning that their conservation benefits that of other species. In a study that looked at mammals in the Americas, they found that the best habitats for jaguar conservation also hosted between 70% and 81% of the other mammalian species found in the region (Thornton et al. 2016). Since jaguars are charismatic species, they could also act as flagship species to encourage the conservation of whole ecosystems in their natural range, helping to achieve a greater goal of regional conservation.

With regards to human society, jaguars have historically held ritualistic, social, and cosmological importance in many different cultures (The jaguar: a… 2020) from the Mesoamerican time period to the current day (Morales Garcia and Morales Garcia 2018). They are both a symbol of balance between life and death and a symbol of strength and protection in addition to being viewed as the perfect animal that lives in a perfect state of balance with its environment (The jaguar: a… 2020). In many ancient cultures, the jaguar was venerated and admired, as shown by the legend at the beginning of this chapter as well as the statue in Figure 7. The extinction of the jaguar would therefore have a significant cultural impact on the native people of the Americas. Moreover, the cultural importance of jaguars could be very beneficial in planning conservation efforts. The bald eagle is a relevant example here as its journey towards recovery was largely aided by its symbolism and importance in American culture (Davis and Nagle 2015, p198-199), and the jaguar could utilize a similar strategy in its conservation efforts.

Figure 7: Ceramic representation of a man-jaguar from the Mayan classic recent era (600-900 CE). “Homme jaguar maya” by Jebulon, CC0 1.0.

Jaguars are also important to many local economies in the Americas. Ecotourism in Central and South America has increased dramatically in the last few decades as more people are visiting national parks to observe unique organisms in their natural habitats. The jaguar in particular has been a boon to the region with regards to this recent boost in ecotourism, helping to bolster local economies (Tortato and Izzo 2017). The Matogrossense National Park in Brazil has even established a management plan for jaguars, allowing ecotourists to observe them within conservation areas (Tortato and Izzo 2017). By learning more about jaguars, people are also more likely to spread awareness about their plight and help fight for their conservation.

Following this theme, one of the most common conservation efforts used in the effort to protect jaguars is educating local communities and collaborating with them to implement new conservation strategies. Agricultural and timber workers are often specifically targeted since their actions can greatly harm the jaguar population if they are not properly aware of the consequences they can cause.

Furthermore, studies have found that people tend to be scared of jaguars, and those who are afraid or have known a person/animal that was a victim of an attack more often favor jaguar persecution (Knox et al. 2019). This is an important factor to consider when planning community-based jaguar conservation strategies. Additionally, older people were more likely to have killed a jaguar, while younger people tended to view this action negatively (Knox et al. 2019), likely because of changing values and growing awareness about the importance of wildlife conservation. Attitudes about jaguar persecution also changed by region, as shown by Figure 8. Since this cultural background also plays a part in people’s perception of jaguars, addressing concerns with locals to lead united efforts for conservation is crucial, especially since a large part of the damage being caused to jaguar populations comes from direct human actions.

Figure 8: Proportion of attitudes towards jaguar killing by area in protected territories of the Bolivian Amazon. The figure shows that there are differing opinions between territories and that around 30% of all respondents favored jaguar persecution. “Proportion of residents who reported killing a jaguar in the past, by area” from Knox et al. (2019), CC BY 4.0

Another common conservation strategy involves monitoring the jaguar population in specific areas to see how they interact with the land and the status of the land (i.e., whether it is used by humans) in order to come up with targeted conservation efforts that will have maximum efficacy in that specific area.

Since habitat loss and fragmentation are two major dangers to jaguar populations, some conservation groups—such as Costa Rica’s National Program of Biological Corridors (Zeller 2021)—have bought land to form protected ecological corridors to connect isolated populations. Although this is not the most effective long-term strategy, it helps conservationists in the short-term by allowing them to devise more efficient long-term plans for maintaining these corridors and ultimately protecting the jaguar population (Root 2019). The importance of these ecological corridors cannot be overemphasized, as they allow for increased genetic diversity by facilitating the breeding of unrelated jaguar populations.

While these privately funded conservation efforts are undoubtedly beneficial, governments must also be engaged in the work of conservationists. To this end, there have been federal recovery goals recently set in place to guide jaguar conservation efforts, which vary by region. Once these have been achieved, the species’ status should be considered for downlisting. Its habitat has been classified into two distinct regions known as recovery units: the Pan-American Recovery Unit (PARU), which encompasses 18 countries from Argentina to Mexico, and the Northwestern Recovery Unit (NRU), which extends from southern Arizona to southwestern New Mexico (USFWS 2018).

In the PARU, the jaguar should be considered for downlisting when its status is changed to Least Concern according to the IUCN Red List criteria. This denotes that threats to the species have been reduced so that its population is no longer at risk of a greater than 30% decline in size (USFWS 2018).

In the NRU, the species should be considered for downlisting when, in key areas over a period of 20 years, it maintains a roughly 60% occupancy in each of the designated core areas, inbreeding coefficients do not increase, an average of at least 30% of the adult population is female, and a large network of high-quality habitat is maintained. This network of habitat must include at least two trans-border linkages that allow jaguar dispersal and there must be strategies in place to mitigate impediments to all such ecological corridors. Furthermore, effective laws must be put in place at all levels of government to ensure that the killing of jaguars is regulated/prohibited, as the threat of direct human killing of jaguars must be decreased in order for downlisting to be considered (USFWS 2018). These laws would ideally also protect other native species that the jaguar relies on (Jaguars… c2021).

The mighty jaguar is at a crossroads. Our actions have not yet damaged them beyond recovery, but unless changes are made the jaguar will suffer the unfortunate fate of so many other species on our planet. The loss of such a culturally, socially, economically, and ecologically significant species would have major repercussions in many communities in the Americas, so it must be fought against at all costs. This is why the previously mentioned conservation efforts are so important, but these are only just the beginning. More needs to be studied about this spectacular species to guide proper action. Further initiatives must be put forward in order to engage people in every level of society across the jaguar’s wide range so their plight will not continue to worsen. In doing so, we hope that one day the jaguar will return to its former glory at the top of its food chain, just as the Mayans observed.

Bibliography

Arias M, Hinsley A, Milner-Gulland EJ. 2020. Characteristics of, and uncertainties about, illegal jaguar trade in Belize and Guatemala. Biological Conservation 250: 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108765

Baker W, Deem S, Hunt A, Law C, Munson L, Johnson S, Spindler R, Ward A. 2002. Guidelines for captive management of jaguars. Jaguar Species Survival Plan 1: 3–13; [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from https://www.jaguarssp.net/Animal%20Mgmt/JAGUAR%20GUIDELINES.pdf

Crawshaw PG Jr, Quigley HB. 1991. Jaguar spacing, activity, and habitat use in a seasonally flooded environment in Brazil. Journal of Zoology 223(3): 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1991.tb04770.x

Davis A, Nagle G. 2015. Environmental Systems and Societies. London: Pearson Education Limited, p 198-199.

de Azevedo FC, Murray DL. 2007. Spatial organization and food habits of jaguars (Panthera onca) in a floodplain forest. Biological Conservation 137(3):391-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2007.02.022

de la Torre JA, Nuñez JM, Medellín RA. 2017. Habitat availability and connectivity for jaguars in the southern Mayan forest: Conservation priorities for a fragmented landscape. Biological Conservation 206: 270-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.034

Estes JA, Terborgh J, Brashares JS, Power ME, Berger J, Bond WJ, Carpenter SR, Essington TE, Holt RD, Jackson JBC, et al. 2011. Trophic downgrading of planet Earth. Science 333(6040): 301-306. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1205106

Garcia Fontes S, Gonçalves Morato R, Stanzani SL, Pizzigatti Corrêa PL. 2021. Jaguar movement behavior: Using trajectories and association rule mining algorithms to unveil behavioral states and social interactions. PLoS One. 16(2):e0246233. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246233

Jaguar (Panthera onca) fact sheet: reproduction & development. 2020. San Diego (CA): SDZGL (San Diego Zoo Global Library); [updated 2020 Dec 4; cited 2021 Feb 22]. Available from https://ielc.libguides.com/sdzg/factsheets/jaguar/reproduction

Jaguars. 2020. Oakland (CA): Conservation Society of California Oakland Zoo (CSCOZ); [cited 2021 Feb 22]. Available from https://www.oaklandzoo.org/animals/jaguar

Jaguars. 2021. Wildlife Conservation Society; [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from https://www.wcs.org/our-work/species/jaguars#:~:text=in%20accessible%20areas.-,Our%20strategies%20include%3A,the%20spectrum%20of%20land%20uses

Jędrzejewski W, Robinson HS, Abarca M, Zeller KA, Velasquez G, Paemelaere EAD, Goldberg JF, Payan E, Hoogesteijn R, Boede EO, et al. 2018. Estimating large carnivore populations at global scale based on spatial predictions of density and distribution – Application to the jaguar (Panthera onca). PLoS ONE. 13(3): e0194719. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194719

Knox J, Negrões N, Marchini S, Barboza K, Guanacoma G, Balhau P, Tobler MW, Glikman JA. 2019. Jaguar persecution without “cowflict”: Insights from protected territories in the Bolivian Amazon. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7: 494. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00494

Law C, Baker W, Deem S, Hunt A, Munson L, Johnson S, Spindler R, Ward A. 2020. Jaguar species survival plan: guidelines for captive management of jaguars [Internet]. Fort Worth, TX: Jaguar SSP Management Group, Fort Worth Zoo; [cited 2021 Feb 22]. Available from https://www.jaguarssp.net/Animal%20Mgmt/JAGUAR%20GUIDELINES.pdf

Morales Garcia AD, Morales Garcia JJ. 2018 Oct 17. Jaguars and culture: Public policies for integrated conservation in Mexico. IUCN [cited 2021 Mar 7]. Available from https://www.iucn.org/news/commission-environmental-economic-and-social-policy/201810/jaguars-and-culture-public-policies-integrated-conservation-mexico

Quigley H, Foster R, Petracca L, Payan E, Salom R, Harmsen B. 2017. Panthera onca (errata version published in 2018) [Internet]. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15953A50658693.en

Ripple WJ, Estes JA, Beschta RL, Wilmers CC, Ritchie EG, Hebblewhite M, Berger J, Elmhagen B, Letnic M, Nelson MP, Schmitz OJ, Smith DW et al. 2014. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science. 343(6167): 1241484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1241484

Root T. 2019. The struggle to protect a vital jaguar corridor. National Geographic; [cited 2021 Feb 28]. Available from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/protecting-jaguars-wildlife-corridor-belize.

Sanderson EW, Redford KH, Chetkiewicz C-LB, Medellin RA, Rabinowitz AR, Robinson JG, Taber AB. 2002. Planning to save a species: the jaguar as a model. Conservation Biology 16(1): 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1523-1739.2002.00352.X

The jaguar: a cultural icon of America. 2020 Feb 28. Wild For Life [cited 7 Mar 2021]. Available from https://wildfor.life/the-jaguar-a-cultural-icon-of-america#:~:text=The%20Jaguar%20has%20had%20a,balance%20between%20life%20and%20death.

Thornton D, Zeller K, Rondinini C, Boitani L, Crooks K, Burdett C, Rabinowitz A, Quigley H. 2016. Assessing the umbrella value of a range-wide conservation network for jaguars (Panthera onca). Ecological Applications 26(4): 1112-1124. https://doi.org/10.1890/15-0602

Tortato FR, Izzo TJ. 2017. Advances and barriers to the development of jaguar-tourism in the Brazilian Pantanal. Perpectives in Ecology and Conservation 15(1): 61–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2017.02.003

[USFWS] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Jaguar recovery plan (Panthera onca). Albuquerque, New Mexico: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. p. 56-92; [cited 2021 March 4]. Available from https://www.fws.gov/southwest/docs/JaguarRecoveryPlansignedJuly2018.pdf

WWF. 2020. Top 10 facts about jaguars. WWF-UK; [cited 2021 Feb 22]. Available from https://www.wwf.org.uk/learn/fascinating-facts/jaguars

Zeller K. 2021. The jaguar corridor initiative: A range-wide species conservation strategy. Connectivity Conservation Specialist Group (CCSG); [cited 2021 Feb 27]. Available from https://conservationcorridor.org/ccsg/what-we-do/projects-and-activities/guidelines/case-studies/jaguar/

A species that is at the highest trophic level in its ecosystem and therefore has no natural predators.

Describes a species can subsist on a wide variety of food sources.

In top-down regulation, a species at the highest trophic level has a significant impact on the population sizes of species that are in lower trophic levels.

A hoofed animal similar to a pig that is found in Central and South America, as well as in the southwestern area of North America.

Describes a species that can eat a wide range of foods and survive in a variety of different habitats.

An animal that feeds primarily or exclusively on animal matter.

Describes a species that defends a particular region and the resources inside of it

Refers to species that are active at night.

In populations that are regulated from the bottom-up, the limiting factors are resources that allow for growth (such as habitat and food source).

A group of organisms within an ecosystem which occupy the same level in a food chain

A species of plant or animal that has a major impact (as by predation) on its ecosystem and is considered essential to maintaining optimal ecosystem functionality or structure.

A process in which a large habitat is split into smaller habitats that are typically isolated from each other.

In this context, depredation refers to the killing of livestock by wild animals - in this case, jaguars.

The recurring period of fertility in female mammals in which they are receptive to mating.

Hoofed mammal.

The age at which juveniles are able to produce their own offspring.

This is regarded as the world's most comprehensive inventory of the conservation status of species. It is compiled and managed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The extinction of a species in a particular area. Species that are extirpated in one region may continue to live in other areas.

The variation of genetic information within a population/species.

According to the IUCN, critically endangered species are those that face an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.

A species for which species conservation efforts are currently unnecessary according to the IUCN.

A powerful effect that occurs when a certain level of a food chain is disrupted and the effects travel over the entire food chain.

The non-living part of the environment.

A species whose conservation efforts indirectly benefit many other species that make up an ecosystem.

A species that is intended to support conservation efforts in a particular region.

A type of tourism that allows for people to safely observe exotic wildlife and support conservation efforts.

A passage between natural habitats of a species that allow individuals to pass freely between these habitats that would be otherwise separated.

Downlisting in this case refers to reducing the jaguar's IUCN designation (e.g. from threatened to least concern). The jaguar is unique in that different populations can have different threat designations.

This is a measure of the probability that two alleles at any locus in an individual are identical. The higher this likelihood is, the more likely it is that harmful recessive alleles will be expressed in the individual. As such, lower inbreeding coefficients are preferable.