41

A cell within a multicellular organism may need to signal to other cells that are at various distances from the original cell (Figure 1). Not all cells are affected by the same signals. Different types of signaling are used for different purposes.

Internal receptors

Internal receptors, also known as intracellular or cytoplasmic receptors, are found in the cytoplasm of the cell and respond to hydrophobic ligand molecules that are able to travel across the plasma membrane. Once inside the cell, many of these molecules bind to proteins that act as regulators of mRNA synthesis. Recall that mRNA carries genetic information from the DNA in a cell’s nucleus out to the ribosome, where the protein is assembled. When the ligand binds to the internal receptor, a change in shape is triggered that exposes a DNA-binding site on the receptor protein. The ligand-receptor complex moves into the nucleus, then binds to specific regions of the DNA and promotes the production of mRNA from specific genes (Figure 2). Internal receptors can directly influence gene expression (how much of a specific protein is produced from a gene) without having to pass the signal on to other receptors or messengers.

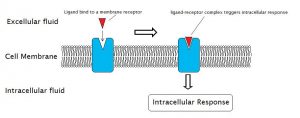

Cell-Surface Receptors

Cell-surface receptors, also known as transmembrane receptors, are proteins that are found attached to the cell membrane. These receptors bind to external ligand molecules (ligands that do not travel across the cell membrane). This type of receptor spans the plasma membrane and performs signal transduction, in which an extracellular signal is converted into an intercellular signal. Ligands that interact with cell-surface receptors do not have to enter the cell that they affect. Cell-surface receptors are also called cell-specific proteins or markers because they are specific to individual cell types.

Each cell-surface receptor has three main components: an external ligand-binding domain, a hydrophobic membrane-spanning region, and an intracellular domain inside the cell. The size and extent of each of these domains vary widely, depending on the type of receptor.

Ion channel-linked receptors

Ion channel-linked receptorsbind a ligand and open a channel through the membrane that allows specific ions to pass through. To form a channel, this type of cell-surface receptor has an extensive membrane-spanning region. When a ligand binds to the extracellular region of the channel, there is a conformational change in the proteins structure that allows ions such as sodium, calcium, magnesium, and hydrogen to pass through (Figure 4).

G-protein-coupled receptors

G-protein-coupled receptorsbind a ligand and activate a membrane protein called a G-protein. The activated G-protein then interacts with either an ion channel or an enzyme in the membrane (Figure 5). Before the ligand binds, the inactive G-protein can bind to a site on a specific receptor. Once the G-protein binds to the receptor, the G-protein changes shape, becomes active, and splits into two different subunits. One or both of these subunits may be able to activate other proteins as a result.

Enzyme-linked receptors

Enzyme-linked receptorsare cell-surface receptors with intracellular domains that are associated with an enzyme. In some cases, the intracellular domain of the receptor itself is an enzyme. Other enzyme-linked receptors have a small intracellular domain that interacts directly with an enzyme. When a ligand binds to the extracellular domain, a signal is transferred through the membrane, activating the enzyme. Activation of the enzyme sets off a chain of events within the cell that eventually leads to a response.

How Viruses Recognize a Host

Unlike living cells, many viruses do not have a plasma membrane or any of the structures necessary to sustain life. Some viruses are simply composed of an inert protein shell containing DNA or RNA. To reproduce, viruses must invade a living cell, which serves as a host, and then take over the hosts cellular apparatus. But how does a virus recognize its host?

Viruses often bind to cell-surface receptors on the host cell. For example, the virus that causes human influenza (flu) binds specifically to receptors on membranes of cells of the respiratory system. Chemical differences in the cell-surface receptors among hosts mean that a virus that infects a specific species (for example, humans) cannot infect another species (for example, chickens).

However, viruses have very small amounts of DNA or RNA compared to humans, and, as a result, viral reproduction can occur rapidly. Viral reproduction invariably produces errors that can lead to changes in newly produced viruses; these changes mean that the viral proteins that interact with cell-surface receptors may evolve in such a way that they can bind to receptors in a new host. Such changes happen randomly and quite often in the reproductive cycle of a virus, but the changes only matter if a virus with new binding properties comes into contact with a suitable host. In the case of influenza, this situation can occur in settings where animals and people are in close contact, such as poultry and swine farms (Sigalov, 2010). Once a virus jumps to a new host, it can spread quickly. Scientists watch newly appearing viruses (called emerging viruses) closely in the hope that such monitoring can reduce the likelihood of global viral epidemics.

References

Text adapted from: OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. October 13, 2017. https://cnx.org/contents/GFy_h8cu@10.118:H4oMpCSi@8/Signaling-Molecules-and-Cellul#footnote1

A. B. Sigalov, The School of Nature. IV. Learning from Viruses, Self/Nonself1, no. 4 (2010): 282-298. Y. Cao, X. Koh, L. Dong, X. Du, A. Wu, X. Ding, H. Deng, Y. Shu, J. Chen, T. Jiang, Rapid Estimation of Binding Activity of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin to Human and Avian Receptors, PLoS One6, no. 4 (2011): e18664.