105

It is easy to see how biotechnology can be used for medicinal purposes. Knowledge of the genetic makeup of our species, the genetic basis of heritable diseases, and the invention of technology to manipulate and fix mutant genes provides methods to treat diseases. Biotechnology in agriculture can enhance resistance to disease, pests, and environmental stress to improve both crop yield and quality.

Genetic Diagnosis and Gene Therapy

The process of testing for suspected genetic defects before administering treatment is called genetic diagnosis by genetic testing. In some cases in which a genetic disease is present in an individual’s family, family members may be advised to undergo genetic testing. For example, mutations in the BRCA genes may increase the likelihood of developing breast and ovarian cancers in women and some other cancers in women and men. A woman with breast cancer can be screened for these mutations. If one of the highrisk mutations is found, her female relatives may also wish to be screened for that particular mutation, or simply be more vigilant for the occurrence of cancers. Genetic testing is also offered for fetuses (or embryos with in vitro fertilization) to determine the presence or absence of disease-causing genes in families with specific debilitating diseases.

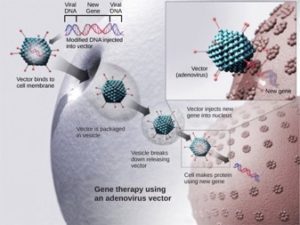

Gene therapy is a genetic engineering technique that may one day be used to cure certain genetic diseases. In its simplest form, it involves the introduction of a non-mutated gene at a random location in the genome to cure a disease by replacing a protein that may be absent in these individuals because of a genetic mutation. The non-mutated gene is usually introduced into diseased cells as part of a vector transmitted by a virus, such as an adenovirus, that can infect the host cell and deliver the foreign DNA into the genome of the targeted cell (Figure 10.8). To date, gene therapies have been primarily experimental procedures in humans. A few of these experimental treatments have been successful, but the methods may be important in the future as the factors limiting its success are resolved.

Traditional vaccination strategies use weakened or inactive forms of microorganisms or viruses to stimulate the immune system. Modern techniques use specific genes of microorganisms cloned into vectors and mass-produced in bacteria to make large quantities of specific substances to stimulate the immune system. The substance is then used as a vaccine. In some cases, such as the H1N1 flu vaccine, genes cloned from the virus have been used to combat the constantly changing strains of this virus.

Antibiotics kill bacteria and are naturally produced by microorganisms such as fungi; penicillin is perhaps the most well-known example. Antibiotics are produced on a large scale by cultivating and manipulating fungal cells. The fungal cells have typically been genetically modified to improve the yields of the antibiotic compound.

Recombinant DNA technology was used to produce large-scale quantities of the human hormone insulin in E. coli as early as 1978. Previously, it was only possible to treat diabetes with pig insulin, which caused allergic reactions in many humans because of differences in the insulin molecule. In addition, human growth hormone (HGH) is used to treat growth disorders in children. The HGH gene was cloned from a cDNA (complementary DNA) library and inserted into E. coli cells by cloning it into a bacterial vector.

Transgenic Animals

Although several recombinant proteins used in medicine are successfully produced in bacteria, some proteins need a eukaryotic animal host for proper processing. For this reason, genes have been cloned and expressed in animals such as sheep, goats, chickens, and mice. Animals that have been modified to express recombinant DNA are called transgenic animals (Figure 10.9).

Several human proteins are expressed in the milk of transgenic sheep and goats. In one commercial example, the FDA has approved a blood anticoagulant protein that is produced in the milk of transgenic goats for use in humans. Mice have been used extensively for expressing and studying the effects of recombinant genes and mutations.

Transgenic Plants

Manipulating the DNA of plants (creating genetically modified organisms, or GMOs) has helped to create desirable traits such as disease resistance, herbicide, and pest resistance, better nutritional value, and better shelf life (Figure 10.10). Plants are the most important source of food for the human population. Farmers developed ways to select for plant varieties with desirable traits long before modernday biotechnology practices were established.

Transgenic plants have received DNA from other species. Because they contain unique combinations of genes and are not restricted to the laboratory, transgenic plants and other GMOs are closely monitored by government agencies to ensure that they are fit for human consumption and do not endanger other plant and animal life. Because foreign genes can spread to other species in the environment, particularly in the pollen and seeds of plants, extensive testing is required to ensure ecological stability. Staples like corn, potatoes, and tomatoes were the first crop plants to be genetically engineered.

Transformation of Plants Using Agrobacterium tumefaciens

In plants, tumors caused by the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens occur by transfer of DNA from the bacterium to the plant. The artificial introduction of DNA into plant cells is more challenging than in animal cells because of the thick plant cell wall. Researchers used the natural transfer of DNA from Agrobacterium to a plant host to introduce DNA fragments of their choice into plant hosts. In nature, the disease-causing A. tumefaciens have a set of plasmids that contain genes that integrate into the infected plant cell’s genome. Researchers manipulate the plasmids to carry the desired DNA fragment and insert it into the plant genome.

The Organic Insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is a bacterium that produces protein crystals that are toxic to many insect species that feed on plants. Insects that have eaten Bt toxin stop feeding on the plants within a few hours. After the toxin is activated in the intestines of the insects, death occurs within a couple of days. The crystal toxin genes have been cloned from the bacterium and introduced into plants, therefore allowing plants to produce their own crystal Bt toxin that acts against insects. Bt toxin is safe for the environment and non-toxic to mammals (including humans). As a result, it has been approved for use by organic farmers as a natural insecticide. There is some concern, however, that insects may evolve resistance to the Bt toxin in the same way that bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics.

FlavrSavr Tomato

The first GM crop to be introduced into the market was the FlavrSavr Tomato produced in 1994. Molecular genetic technology was used to slow down the process of softening and rotting caused by fungal infections, which led to increased shelf life of the GM tomatoes. Additional genetic modification improved the flavor of this tomato. The FlavrSavr tomato did not successfully stay in the market because of problems maintaining and shipping the crop.

References

Unless otherwise noted, images on this page are licensed under CC-BY 4.0 by OpenStax.

OpenStax, Biology. OpenStax CNX. May 27, 2016 http://cnx.org/contents/s8Hh0oOc@9.10:rytx-nDe@3/Biotechnology-in-Medicine-and-