PUBLISHING PRACTICES

11 Managing Your Creative Works

Kathleen DeLaurenti

Understanding publishing systems and identifying stakeholders helps us improve our search strategies and understand the relationships among creators, copyright, and publishers. The next step is to use this information to successfully plan a research-creation project that accounts for these issues so that you can make sound legal and ethical decisions about distributing or performing your research-creation projects.

In the Part II: Copyright Essentials, we explored the legal considerations required to manage copyrights when performing, displaying, and teaching works created by others. This chapter shifts focus to your rights as a creator. We examine how your personal values and artistic mission shape the ways you can make your work accessible. We aim to deepen your understanding of your own rights and how they can align with your creative goals and dissemination strategies.

As we know, scholars in other disciplines who focus on sharing their work in text-based formats increasingly value open access to expand the reach of their work. As a musician-scholar, you may engage in that system of scholarly publishing at some point in your career, and your strategies for disseminating that work may align well with standard open access principles. You may use different approaches, though, when considering how to publish and share research-creation projects that are embodied in other media like live performance, installations, sound recordings, or film. Modern distribution of a musician-scholar’s work often includes strategies for freemium or premium streaming models that can be easy to use, such as SoundCloud, or seem impossible to distribute with, like Netflix.

Before you make decisions that can have long-term impact on your work, it’s important to understand the implications and options available to you.

Centering Your Artistic Mission

Musician-scholars sometimes feel like maximizing income is the only issue when making decisions about disseminating work. Conflating managing your copyrights with making money can lead to situations where copyrights are transferred for the promise of maximizing income. These transfers can sometimes have a negative impact on your decision-making power in the future. Just as the Copyright Act aims to create a system that balances the interest of copyright holders and users, when you create work, you should balance your economic interests with your artistic mission.[1]

To do this, you will need to define your artistic mission. It is common to define your mission as a series of questions:[2]

- How do artists you admire communicate consistency and authenticity?

- Who is your audience?

- Ask yourself what, why, and so what?

Answer to these questions can help you communicate your values to funders when developing your mission around a project or seeking a new direction for your work. Answering these questions for yourself also provides you with solid values to lean into when thinking about how to disseminate your work.

In a world before streaming and the internet, technology limited the avenues where multimedia work could be accessed. Now, significant amounts of media are available to anyone with access to the internet. This has had profound impact on the economies of sharing and accessing music and multimedia. This near-universal access also provides you with unprecedented control over building your plans for sustainability and determining what role disseminating your work plays in your career.

In the past, artists sought backing from record labels to invest significant financial resources into recording, duplicating, marketing, and distributing an album. Sales were needed to recoup those investments before artists were paid.[3] This system traditionally asks artists to transfer copyrights to record labels and publishers, providing them with management services in exchange for control over their exclusive rights.

Today, you can record, master, and distribute a professionally produced sound recording with minimal personal investments. While funding artistic ventures can be challenging, new technology provides more opportunities to directly engage with your audience. Artists are leveraging crowdfunding sites like Patreon, IndieGoGo, or Kickstarter to build relationships with their audiences and change existing economic models. Instead of streaming, sales, and licenses recouping the costs of recording and releasing an album, artists can raise funds for recording equipment, studio time, and labor before a record is even released.

Like new OER models where institutions and funders compensate scholars when their work is first made instead of waiting for royalties after publication, these tools allow musician-scholars to retain control over their artistic work and career sustainability. Once you have a defined mission, you can build your approach to rights management and dissemination as one part—but not the only part—of your sustainable career.

Breaking Down Your Research Topic

Hyo-Eun has suggested recording the songs they are arranging to share on their website and to post to streaming services.

Hyo-Eun has suggested recording the songs they are arranging to share on their website and to post to streaming services.

She knows that there aren’t any copyright permissions they need to use the music, but she also knows they need to make some decisions about who will make long term decisions about the recordings, what happens with any royalties they collect, and what terms they might want to apply to the use of the recordings.

Hyo-Eun starts researching the services they plan to use to make the recordings available. She wants to understand their requirements and how they align with the copyright issues for this research-creation project. They’d like to host the audio on SoundCloud to embed in their site and release it to major streaming platforms such as Spotify and Apple Music.

Know Which Rights You Are Working With

When you start any project, it is critical to identify which rights you will need to manage throughout the project. It is important to develop a structured way to understand which scenarios might apply to your research creation project. A rights inventory that helps you track and understand all the copyrights in your project can be an incredibly useful tool.

The authors often work with students who start with a project idea and then hope to figure out the rights later—when it could be too late. Early in your career, especially when collaborating with colleagues, it can be uncomfortable to make formal agreements about your artistic work. However, just like communication is the cornerstone of all relationships, explicitly understanding and communicating rights and responsibilities from day one will lead to a healthy collaboration in managing your copyrights.

Creating Original Works

When you are creating original work, below are some of the questions you want to ask.

Are you a joint copyright holder with another creator?

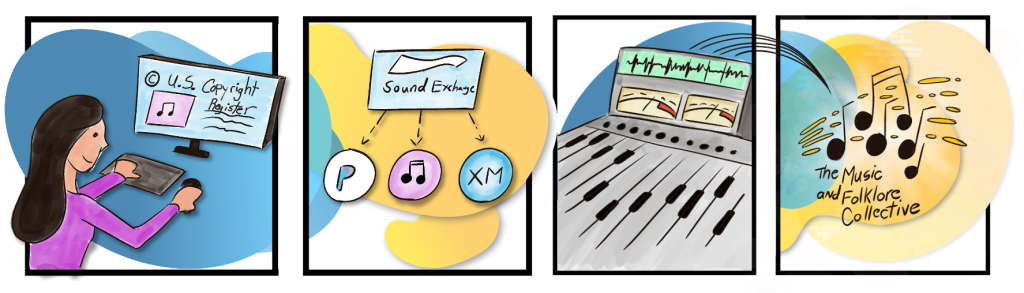

Filing to register your copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office is a good way to ensure you and your collaborated agree on their creative role while also ensuring you secure the exclusive rights you need to defend your copyright from infringement claims. You can register sound recordings or musical works with multiple copyright owners.

Which copyrights will you need to manage before publication?

This could include a score, a sound recording, or a live performance video. It is important to know who the copyright owner will be for each component of your live performance or recording project.

Does your project include any works where you are not the copyright holder?

Do you need to license text, music, images, or other copyrighted works as part of the performance or recording project?

Are those copyrights owned and managed by third parties?

This could include text you want to set or music you want to sample or interpolate. Sometimes, the creator of a text or musical work is not the copyright owner. It’s important to identify and contact the copyright owner when you need to license a copyrighted work.

Are any of these works in the public domain?

You can always freely incorporate public domain works into your live performance or recording project without securing any copyright permissions.

Copyright Resource

Using Copyrighted Works of Other Creators

When creating a performance project that includes the copyrighted works of other creators, you may ask slightly different questions.

Are you performing solo or alone?

When you perform with collaborators, decide if you will share copyright in any recorded versions of the performance.

Are the works you plan to perform copyrighted or in the public domain?

If they’re in the public domain, you don’t need any additional licenses for performing publicly, livestreaming, or making recordings in any format available.

Are you planning to perform live or are you also streaming, recording, or making a recording of the performance live after it occurs?

If you are performing live, investigate whether you need a public performance or if the venue has one already. Find out if you need additional licenses for streaming or making recordings available on demand.

Is any recording you want to make available going to be audio only or audio/visual?

Audio recordings of copyrighted work posted to many streaming platforms will be covered by the platform licenses.[4]

Who is making the recording?

Find out who is recording the performance. Determine who owns the copyright of any audio or audiovisual recordings of the performance. The copyright might be owned by the recording engineer or venue, or qualifies as work for hire because you hired someone to make a recording.

Rights Inventory

A rights inventory determines which copyrights are involved, who owns them, and what kind of permissions you will need to complete your research-creation project. Making this inventory will also help you understand what rights may need to be managed for the duration of your new work’s copyright. This is important to know, as any copyrighted work you produce will be copyrighted for 70 years after your death. Here is an example of what a rights inventory might look like for a research-creation project.

| Work Title | Creator | Copyright Owner | License Required | Additional Concerns |

| Arirang | Unknown (folksong) | Public Domain (estimated 600 years old) | None | Used as a resistance anthem during Japanese occupation; research the song to determine suitability |

| Arirang (recorded by our group) | Luis as recording engineer; All group members as performers | All group members | None | Include in rights management plan |

| Translation of text | Hyo Eun | Hyo Eun | None | Include in rights management plan |

11.1-Dig Deeper

Create a Rights Management Plan

Once you have inventoried the copyrights involved in your research-creation project, you will need a plan for managing any rights that you and your collaborators control. This may involve making some decisions about how any research-creation outputs that have new copyrights will be published or shared. A copyright management plan outlines which rights are involved, who will manage them, and how these rights align with your artistic mission.

When you plan what rights you might need to license, which new copyrights are being created, and who will own them, you can also identify what kinds of financial resources you will need to secure and manage permissions. Tying this to your artistic mission helps you make a case to funders that can help you develop sustainable alternatives for your career that do not rely primarily on complex royalty systems.

Breaking Down Your Research Topic

Sebastian and the other musician-scholars know that they want their research-creation project to be something that other musician-scholars can apply to additional cultural contexts.

They decide that they do want to collect royalties from their streaming sound recordings, so the group decides not to assign creative commons licenses to the musical arrangements or the sound recordings. The do decide to register the arrangements with the U.S. Copyright Office and with the composers’ PROs. They will post the arrangements for free online; they know that the public performance licensing system won’t collect much in royalties, but they do want to re-invest any royalties back into maintaining the website or other hosting costs.

However, they do want other musician-scholars to be able to adapt their translations and use the images that their friend Gil was hired to make. They hope other musician-scholars will be inspired to add additional content to this project representing cultures that they weren’t able to include in this project. To do this, they decided to ask their illustrator to apply a creative commons license to their illustrations so that they can be reused and adapted for other cultural contexts in appropriate ways.

This kind of mission-driven decision making can be compelling to funders and could help Sebastian and their colleagues make a case for in their grant budget for funding that not only compensates Gil’s initial contribution, but also feels appropriate to compensate them for future uses.

| Work Title | Creator | Copyright Owner | Publication Rights | License Terms | Artistic Mission | Royalty Distribution |

| Arirang English Translation | Hyo Eun | Hyo Eun | Release into Public Domain | CC.0 – public domain | Maximize access for use in educational materials; include in funding request | |

| Arirang illustration | Mary | Mary | Release with creative commons license | CC-BY-NC: noncommercial reuse allowed | Maximize ability for reuse and publication in additional educational formats | |

| Arirang recording | All group members | All group members | Release © through a sound recording aggregator/SoundCloud | © | Allows us to maximize the platforms where our work is shared; generates passive income | Create an agreement where one group member manages royalties, and they are reinvested in supporting our website and surplus revenue is distributed equally after thresholds are met |

11.2-Dig Deeper

Understanding Creative Commons

Introduced in Chapter 10: Publishing and Accessing Information, creative commons licenses allow a copyright holder to share their work with audiences and other creators without requiring a request for permission. You can apply creative commons licenses to any distinct copyrighted work. That means that when you create your copyright management plan, you can choose to release some components of your research-creation project under traditional publishing.

There are some significant aspects of creative commons that are important to consider when using these licenses. Creative commons licenses always require attribution to the creator of the original work. You can observe this in action in Chapter 4: Preparing to Search which was, in part, adapted from another OER. There are also images throughout this book that were used or adapted under creative commons licenses.

Creative commons licenses do not change the copyright status of the work. They simply allow copyright holders to grant some permissions related to exclusive rights. Any exclusive rights that are not detailed in the license are still controlled by the copyright holder. For example, the most restrictive creative commons license, the CC BY-NC-ND license simply allows anyone to share a copyrighted work. It does not allow commercial use or modifications of the licensed work.

Creative commons licenses cannot be changed once you’ve used them! The licenses rely on users resharing without permission from the copyright holder. If a license could be changed, there could be multiple versions of the same copyrighted work with different licenses resulting in a crazy-quilt of different permissions. To summarize, any creative commons license applied to a work lasts for the duration of any copyright protection.

There are some specific issues relating to music and creative commons licenses. These licenses generally require you to forfeit royalties for compulsory licenses generated from downstream uses. That means that if you release a musical work under a CC BY-4.0 license, you may not be able to collect royalties from recordings that others have made of—or derived from—your musical work.[5]

Generally, creative commons licenses may make the most sense in your distribution strategy for works where you are compensated in advance or in situations where you often aren’t compensated at all, such as traditional scholarly publications. In these instances, you may have less concerns about potential income from uses covered by a creative commons license and you can more easily choose license options that optimize sharing.

Our hope for this book is that learners and educators will translate, adapt, and reuse it broadly.

Music Publishing

Music publishing can seem even more opaque than publishing your written work with a scholarly publisher. Unlike scholarly publishers, music publishers often do not make the terms of publishing agreements publicly available. Even performing rights organizations do not have specific, transparent terms explaining how public performance royalties are determined and what rates you can expect to be paid. It can be confusing to know how to get started and what a good publishing agreement will look like for you.

Understanding copyright and publishing basics is important, whether you are accessing copyrighted materials or publishing your own work. In this section, we’ll focus on navigating publication of your musical work. As Sarah Osborn notes, publishing and copyright are linked.[6] Given that copyrights related to publishing can be a source of income, it is important to examine this relationship.

Understanding these income-related concerns also helps to determine what alternative funding you might pursue for projects where you want mission-driven alternatives to traditional publishing. When deciding how to release this textbook, the authors spoke with colleagues who had published traditional textbooks to better understand what their experience with royalties was. We found that the publishing contract for our open education book is on par with two to three years of royalties for some traditional textbooks. Because of changes in technology and the law, it’s reasonable to assume that this book will likely need revisions in two to three years to remain useful for readers. Given those facts and our desire to make this information more accessible to musician-scholars, publishing it as an open textbook made sense from both economic and mission-driven perspectives.

Publishing Musical Works

Congratulations! After completing your first research-creation masterpiece in the form of a new composition, you are eager to get it out into the world, but where do you start? How do you get your work published?

Of course, you hope the music publishing industry will hear your work and immediately offer you a contract. However, in a competitive music world, highly regarded publishers such as Boosey & Hawkes do not accept unsolicited submissions from composers.[7]

However, you will still need to understand how basic, traditional publishing agreements work. Generally, when you sign with a publisher, you assign the copyright in your music to the publisher. They will use their marketing, public relations, and legal teams to have your music performed and licensed to generate royalties. In addition to transferring your copyright to them, the publisher will generally claim 50% of all royalty income from licensing, sales, and rentals of your work. The main ways publishers work to generate those funds are:

- Rental of performance scores for orchestral or large dramatic works

- Licensing of public performances

- Licensing of grand rights for dramatic works

- Mechanical licensing from works recorded for CD or streaming distribution

- Licensing music in television, film, and other audiovisual works

- Sales of musical scores (in print and/or digital)

- Permissions for excerpts, arrangements, sampling, or other uses[8]

Plainly, publishers invest significant resources into generating revenue from the composers in their catalog. While this can be beneficial, it’s important to understand what this means for you as the composer. A publisher in control of your copyright can make all the decisions about how your music is used. You may want a podcast to feature your music or for your friend to livestream a performance, but the publisher is now the only entity that can grant those permissions. And in some situations, the publisher’s decision might not align with your artistic mission.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this became an issue for many composers and performers. We saw musicians trying to come together to find ways to create music and community online. But because permissions and contracts were still required from publishers in many circumstances–especially for posting streaming performances on platforms like YouTube or Vimeo–composers sometimes saw these performances silenced or removed from the platforms all together. Publishers were not always equipped to respond to performer needs and couldn’t come to an agreement in a timely manner. In other situations, composers wanted to give their friends permission to perform their works, but discovered that they had transferred that right to their publisher.

What are the options for a composer who wants to spend more time composing than managing a publishing business? Some traditional publishers will offer an agency deal, where they administer some of your publication rights and you continue to own your copyright. There are also companies like Bill Holab Music that offer a suite of services for composers invited to work with them.[9] Their model provides many of the services of a traditional publisher, but leaves composers in control of—and responsible for—managing their copyrights.

Self-publishing through a sheet music platform or through your own website is also an increasingly popular option. If you decide to use a platform like SheetMusicPlus, Theodore Presser, or ArtistShare it is important to be aware of their terms and conditions for selling your music.

The first thing to understand about digital scores is that they don’t function under first sale the same way that a print score does. That means that if someone buys a digital score, they can’t resell, lend, or share that score without additional permissions. For example, when you buy a print edition of a string quartet, the publisher generally sells the parts as a set. When the score arrives, the parts can be distributed to each member of the string quartet. If you purchased the same set of parts digitally, under the licensing terms for some online score distributors, you must buy a set for each member of the quartet. Understanding how the online platform works is important to meet the expectations of your consumers. Many musicians wouldn’t expect to buy four sets of digital parts just because they are digital and not print scores. Generally, you will license digital content, not sell it, which makes the details in those licenses important.

A few things to explore when deciding on using a self-publishing platform versus setting up your own store on your website:

- What terms does the platform allow you to customize for buyers?

- Can you provide specific terms around lending, reselling, etc.?

- What percentage of your sales prices are you comfortable sharing with a publishing platform?

- Does the platform use digital rights management software that limits who can access a digitally licensed score?

- Can your scores only be used on the device where they were downloaded? Through a specific app?

- Does the platform provide terms that allow libraries or other cultural heritage institutions that archive and lend musical scores to add it to their collection?

- What happens if you post scores online without any of these terms? Aren’t all kinds of information posted online to be used?

Some composers, like Pulitzer Prize-winner Raven Chacon, post their scores for free on websites of musicians who commissioned their work or on their own websites. Can’t you just use those scores?

The reality is that the use of those scores is still very limited. If they’re available with a prominent download option, then you can safely assume that the person hosting those files allows you to download them. However, you may still need additional licenses to do anything with them, including perform them. Because copyright is automatic in the United States, anything posted on a website is copyrighted, and the copyright holder fully controls the rights to use them unless they provide explicit license terms about how it can be used.

The Music Library Association(MLA) has endorsed a helpful model purchase and licensing agreement that you can use if you want to make your work available to libraries.[10]Models like this can help you understand how you work will be used in the library. It allows you to adapt the agreement so that when your compositions are added to a library collection, you won’t need to engage in negotiations with every library that wants to add it to their collection.

This model is a purchase and license agreement so that it is clear to both parties that you are selling a PDF file and also granting some permissions for its use. These permissions are clearly articulated so that you know what permissions you are providing. In the model, these permissions align with practices that users expect from library print collections. They want to download or print them for analysis and mark-up, place them in course reserves for study, share them through inter-library loan, and use technology to preserve them for the future. You will see that public performance is not included in the MLA model. Performers still need to secure any licenses required to record, perform, or distribute performances of compositions added to library collections under these terms (just like they would with print scores!), and you will receive appropriate royalties for any of those activities.

Without such models, libraries are finding that many composers are unsure about how to negotiate licensing terms to sell and license digital scores for library collections. At Peabody’s Arthur Friedheim Library, many of the composers who we approach about adding their digital scores to our library never respond at all. Independent composers who contribute their work to libraries may see advantages from making their work accessible. Scores sold to libraries can lead to public performances and recordings that can raise a composer’s profile and generate income from additional licensed uses.

Publishing Sound Recordings

Publishing sound recordings of your research-creation projects is easier today than ever before. It can seem daunting to understand how to move forward with making your recordings available while continuing to have a sustainable career. However, high-quality recordings are still an important way for potential clients to hear your performances, no matter how they access them. Understanding some basics about releasing sound recordings prepares you to take advantage of the do-it-yourself resources now available.

First, it’s important to understand who owns the copyright in sound recordings. When producers, engineers, and performers enter a recording studio, the law does not determine who owns the copyright.[11] This is determined through contractual agreements. It is also important to remember that the copyright for a sound recording resides in the creative capture of an audio performance and does not include the copyright to any of the musical works being recorded.

The most common traditional agreement between a performer and a record label is one where the label invests in all the costs associated with making, marketing, and managing a recording. In exchange, performers transfer any copyrights they might have in the recording to the record label. Sometimes, a contract will outline any performances of the recordings as works for hire; in this case performers do not have any copyright ownership in the recordings.

Generally, performers will receive sound recording royalties based on contracts. If the performers are also the composers of the works on the recording, they will receive separate royalties from a PRO for the musical works. This can be confusing, so let’s look at an example.

You compose a song cycle and record it with a singer. You agree that you will retain the copyright to the recording and the musical work. For the sound recording you receive the following:

- Digital performance royalties from digital audio transmissions

- Master royalties from streams on streaming platforms or use in sampling, television, film, or other audiovisual works

- Reproduction royalties from sales of physical recordings or digital downloads

For the composition fixed in the recording, you receive the following:

- Public performance royalties from all public performances (live and online)

- Mechanical royalties from streams, digital downloads, and physical sales (and from subsequent recordings made by other artists)

- Synchronization royalties from use of the musical work in television, film, or other audiovisual works

- Other licenses, like interpolations or arrangements

The singer you collaborate with would receive a contractually agreed on percentage of sound recording royalties and no royalties from the musical work. Performers also get a statutory royalty for digital audio transmissions of sound recordings—think SiriusXM or Pandora—but all other royalties generally come from the party managing the sound recording. In this example, it might be you. It could also be the record label or a rights management company that manages all of the copyrights for a fee.

Historically, record labels worked on a cost recovery basis: Artists were paid an advance to cover all aspects of recording, marketing, and distributing a recording but did not receive royalties until those costs had been recovered by the record label. Today however, most classical music labels require performers to pay for the recording, duplicating, and marketing costs of a new recording.[12]

If you decide to release your work independently, you may want to understand how royalties will be paid. With so much confusion about royalties and streaming, it can be hard to make sound decisions about how to release a recording. How royalties will be distributed on a project can also be complex, depending on how you structure your business and contractual relationships with your collaborators.

In 2016, a breakdown of streaming on Spotify showed that for every $1 earned, a major label artist earned $0.1814, an independent label artist earned $0.3999, and self-released artists earned $0.6418 on Spotify.[13] These figures reveal the cost of having a label release your music. But self-released music pays you back for the labor you invest.

If you’re recording a musical work copyrighted by someone else, you may need to factor in a mechanical licensing fee for distributing a recording of that work. As we learned, with the launch of the Mechanical Licensing Collective, you generally do not need to file a Notice of Intent with the U.S. Copyright Office or pay mechanical licensing fees for digital-only releases.[14] However, if you are releasing your recording through Bandcamp,[15] physical CDs, or vinyl you still need to follow the notice and licensing procedure and pay a mechanical license as outlined by the U.S. Copyright Office.[16]

There are pros and cons to self-publishing your music and sound recordings. It is important to think not only about the project you are working on today but also how you want to use it in the future and which copyrights you think will be important to retain. Your publishing choices impact the ways your audience can access your music. But they can also impact how you can use your own music in the future, so these decisions are a critical part of sharing your work.

Conclusion

In this chapter we uncover key publishing strategies and considerations essential for musician-scholars. We take a comprehensive look at how to balance the protection of your creative rights with the desire to share and publish work in an increasingly digital world. We also explore the legal frameworks and ethical dilemmas that shape the way creative content is controlled and disseminated. These insights are not just theoretical constructs but also vital tools for navigating the real-world challenges faced by musician-scholars. These lessons form a critical foundation for anyone seeking to make informed decisions about their creative output in a landscape that is as legally complex as it is artistically rich.

Key Takeaways

Define your artistic mission and values to guide decisions about disseminating your work. This alignment ensures that your economic interests and artistic goals complement each other.

At the start of any project, use a rights inventory to identify all copyrights that are implicated in the scope of your work. Knowing the copyright status of every copyright in your project helps you create an effective copyright management plan.

Create a copyright management plan to understand near and long-term copyright management for your research-creation projects. This includes logging decisions on publication and sharing of your work. This plan should align with your artistic mission and consider financial resources needed.

Learn about Creative Commons licenses to share your work broadly without requiring permission for each use. This knowledge allows for strategic decisions in your copyright management plan.

When you consider self-publishing on platforms or your website, understand any terms regarding digital rights management, first sale, and consumer expectations.

Make decisions not just for current projects, but also consider how you want to use your work in the future. Your publishing choices affect both audience access and your future usage rights.

Media Attributions

- Publishing concept © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Using Copyrighted Works © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow, Chokepoint Capitalism (Beacon Press, 2022) https://www.google.com/books/edition/Chokepoint_Capitalism/CzuAEAAAQBAJ?hl=en. ↵

- Adapted from Zane Forshee, Christina Manceor, and Robin McGinness, The Path to Funding: The Artist's Guide to Building Your Audience, Generating Income, and Realizing Career Sustainability (The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University, 2022), https://pressbooks.pub/pathtofunding/. Available under a CC-BY-4.0 license. ↵

- Albini, S. “The Problem with Music,” The Baffler, September 30, 2012, https://thebaffler.com/salvos/the-problem-with-music. ↵

- Notably, at the time of publication, Bandcamp does not have any public performance or mechanical licenses in place and if you want to release music on that platform, you will need the rights necessary to stream and sell your digital downloads or physical copies on Bandcamp. ↵

- “CC BY 4.0 Legal Code | Attribution 4.0 International | Creative Commons,” accessed February 20, 2024, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode.en. ↵

- Chris Dromey and Julia Haferkorn, The Classical Music Industry (Milton, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), https://worldcat.org/title/1031314250. ↵

- “Boosey & Hawkes: The Home of Contemporary Music,” accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.boosey.com/aboutus/help/. ↵

- Marc D Ostrow, “How Composers Earn Money from Their Compositions,” n.d. ↵

- “About Us - Bill Holab Music,” Bill Holab Music, accessed November 7, 2023, https://billholabmusic.com/about-us/. ↵

- “A Model for Purchase and Licensing of Digital Scores – MLA News,” accessed November 27, 2023, https://wp.musiclibraryassoc.org/a-model-for-purchase-and-licensing-of-digital-scores/. ↵

- “Author(s) of the Sound Recordings | U.S. Copyright Office,” accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.copyright.gov/eco/gram-sr/author.html. ↵

- Jeffrey Arlo Brown, “Big Breaks,” VAN Magazine, November 12, 2020, http://van-magazine.com/mag/orpheus-classical/. ↵

- “How Does Music Streaming Generate Money?,” Manatt, accessed November 27, 2023, https://manatt.com/insights/news/2016/how-does-music-streaming-generate-money. ↵

- “Section 115 - Notice of Intention to Obtain a Compulsory License | U.S. Copyright Office,” accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/sec_115.html. ↵

- As of this writing, Bandcamp is not a licensee with the Mechanical Licensing Collective. ↵

- “Section 115 - Notice of Intention to Obtain a Compulsory License | U.S. Copyright Office.” ↵

research that includes performative or non-text creative aspects as the result, motivation, or methodology for the research itself (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

a written expression of your current artistic goals and motivations

a term that describes scholarly publications that are freely available to the public

a musician who has integrated research into their artistic identity and practices

a term used to describe models where a user needs to create an account but can access information for free in exchange for ad placement

a subscription model that provides access to specific content to subscribers, sometimes with benefits such as ad-free experiences

the person, company, or organization that owns the exclusive rights to a copyrighted work

any textbook or learning material that is made available under an open license that allows instructors and learners to retain, reuse, remix, revise, and redistribute the material

the payment you receive for a licensed use of your copyrighted musical work or sound recording

a comprehensive list of the copyrights involved in a given research-creation project

an excerpt of a sound recording that is used in a new musical work

the process of taking a part of an existing musical work (not the sound recording) and incorporating it into a new work; classical musicians often refer to this as musical quotation

the public domain refers to information sources whose copyright has expired. any information sources that are in the public domain can be freely reused without permissions.

defined in copyright law as a performance that is "open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered" or by transmitting the work to be received remotely by the public

a plan where you manage the actual permissions process and document permissions granted for using copyrighted works in your research-creation project

one of six licenses managed by creative commons that copyright holders use to give permission in advance to share, reuse, and adapt their copyrighted works by following specified conditions on how the work must be cited, shared, or modified

a membership organization that collects royalties for public performances and distributes them to publishers and composer/songwriters

a website service that allows composers and songwriters to sell physical copies or license digital copies of their work to customers

when you create a copyrightable work as part of the scope of your employment, it is a work for hire and your employer is the legal copyright holder of that work

required by law; in the case of music royalties, these are royalties that are defined in copyright law