RESEARCH FOUNDATIONS

1 What Is Research?

Kathleen DeLaurenti

Why Research?

What is the foundation of music research in the 21st century? When we think of a foundation, we might immediately imagine buildings, maybe even libraries and universities where scholars conduct research surrounded by dusty volumes. But in this book, we provide the foundations to understand the unseeable systems that manage the organization, distribution, and access to knowledge that every musician-scholar needs to know. Together, we will also grapple with the difficulties of defining what research is so that musician-scholars will locate the ways that research and practice are intertwined in the arts.

While there are incredible artifacts and manuscripts waiting to be explored in countless archives and museums, many of us go about our daily lives with miniature computers in our pockets. Providing nearly instant access to terabytes of information, our cellphones connect us not only to our friends and family, but also to news, books, documentaries, music, films, and productivity tools. As our lives continue to intertwine with technology, the line between work and personal life only blurs even further. The ongoing avalanche of information has also blurred the lines between learning and research.

The COVID-19 pandemic made many of us even more aware of how blurring definitions of learning and research can impact our society during a global crisis. Researchers worked overtime to understand the pandemic and the disease itself while making advances in treatment. But many people outside the medical community found it difficult to sift through information and find trusted research to make informed personal public health decisions. Arguments about vaccine safety were common on social media. We found ourselves confronted with politically motivated disinformation campaigns injected into addition to an overload of user-generated content designed to generate advertising revenue. People who supported and disapproved of vaccines claimed that their positions were right because they had “done their research” by watching online videos or cherry-picking articles that supported their beliefs. Others argued that merely consuming research on a topic did not constitute conducting actual research. There was near constant confusion about who had expertise and some communities saw first-hand how acting on shared misinformation could have serious repercussions.

Many novice musician-scholars also struggle with understanding where learning stops and research begins. Some overestimate their research skills; others underestimate their research skills but aren’t sure how to gain more proficiency with research. Faced with an overload of information and unsure of who to trust, some musician-scholars are concerned that the work they do as creative researchers doesn’t qualify as research. Others may do too little research. As a musician-scholar, it is important to understand that you can do research without a tenure-track faculty position; but your research must be grounded and scoped to the context of your work. It should also be thorough enough that it demonstrates going beyond cherry-picking evidence to make a persuasive point. It should summarize and synthesize existing scholarship to take a multiplicity of perspectives into account.

It may be surprising that there is so much confusion over how to define research. Even researchers themselves have been grappling with this long-standing problem. We can start by examining how research is defined in The Belmont Report, the 1978 landmark work that provided researchers in the United States with guidelines for ethical practices and protocols for human subjects research. The report defined research as “an activity designed to test a hypothesis, permit conclusions to be drawn, and thereby to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge (expressed, for example, in theories, principles, and statements of relationships).”[1] This definition helps us locate the line between our learning practices and the actual work of research.

As you work through this book, you will learn how knowledge is produced, shared, and disseminated in order to embark upon research at any point in your creative process. We also introduce frameworks to help you assess your information needs and make your research process efficient and clearly defined. This prepares you for a research landscape where search engines, algorithms, and search interfaces are constantly changing. You will also have the opportunity to practice and apply skills in any research environment available to you. You do not need expensive database subscriptions or an academic library membership to try this book’s exercises. By understanding the broader perspectives and historical roots of publishing and knowledge-sharing systems, you can better evaluate and leverage any research tools available.

In the previous book in Peabody’s LAUNCHPad series, The Path to Funding: The Artist’s Guide to Building Your Audience, Generating Income, and Realizing Career Sustainability, the authors emphasize aligning your artistic mission with your audiences and funders to build a sustainable career.[2] While your artistic mission is inherently personal, research can demonstrate the value of your art to possible funders and can connect to your audience.

“I never asked why music exists. I think I should have asked that much, much sooner… Once I started asking those questions, I realized that I could approach music in a more holistic way.” Kyoko Kitamura

When you step back and ask questions to better articulate your artistic mission or fill in the gaps for a grant application, you will discover where research fits into the process of communicating the value of your work. Research in a creative context can happen before a performance, be expressed in performance, and even become the performance itself. When you strategically pair your mission with a research plan in performance, education, or community engagement work, you are also better equipped to assess the success of your creative projects and share those results with audiences and funders. Understanding first what kind of context might drive your research needs and then clearly identifying those research needs is as important as a clearly articulated mission.

Scientists have not often thought about sharing their research beyond a scientific publication but musician-scholars are always planning mission-driven approaches to sharing their research results. In the following chapters, we create a framework for research in a creative context. You will integrate research into your artistic practice to support achieving your artistic mission—from the start of your creative work to building longer-term career plans. But first, let’s expand on what we mean by research in a creative context.

What Is Research?

What is research? Historically, this simple question has proven difficult to answer.

- Is reading scholarly articles research?

- What about exploring a new topic on industry websites?

- Does research only happen when experiments are conducted in scientific labs?

Since 2018, we have asked hundreds of students to define research. The overwhelming response they share is rather simple: Research is the process of compiling facts and evidence to support a thesis.

When musician-scholars transition from an educational environment to a professional one, some believe they are leaving research behind. It’s tempting to think your research career ends when you submit your last term paper, but research involves many different methods and can be done using many different methodologies. Your artistic work can span a research spectrum that includes everything from gaining expertise in a performance practice to collaborating with teaching artists on research studies. Unlike laboratory scientists, you won’t emerge from the practice room with a scholarly paper ready for peer-review! As an artist whose research is almost inseparable from practice, you are much more likely to take the stage for a very different kind of evaluation from an audience.

Yet it is important not to oversimplify the role of research in your artistic life. Many young musicians have a narrow view of research. They may think it is limited to the work they do to understand a musical composition they are learning for the first time. However, that assumption ignores many kinds of creative research contexts that are often critical to developing and advancing your artistic process.

In Chapman and Sawchuk’s article “Research-Creation: Intervention, Analysis and ‘Family Resemblances,” the authors establish a framework for understanding the different ways researchers in creative fields approach their work. They introduce the term “research-creation” to help us define new kinds of research that encapsulates contemporary media experiences and modalities of knowing that have been emerging from social sciences and humanities disciplines.[3] Research-creation, which is becoming a standard term in Canadian scholarship, has been paralleled by similar terms in other regions.

In Britain and Australia, scholars refer to this kind of work as “practice as research,” while in the United States, the term “arts-based research” is commonly used. Highlighting the convergence of these two domains, these terms attempt to articulate how creative professionals integrate practice and research in their work. However, practice as research seemingly conveys that merely performing music is research. Similarly, arts-based research can often be confused with research about the arts. We use research-creation in this book to center the inseparable relationship between research and creation.

1-1. Dig Deeper

Reflect on how you feel about research today in your research journal.*

- How do you define research for yourself?

- What research skills do you feel confident about?

- What research skills do you want to develop?

*we recommend keeping a print or digital research journal to document the development of your research-creation projects

Modalities of Research-Creation

To better understand the ways in which research and creation intertwine, Chapman and Sawchuck articulate four modalities of research-creation.[4] Whether you are preparing new repertoire, realizing a new performance practice, or collaborating with a community, you are certainly performing or composing. Beyond your artistry, you are also engaging in research-creation practices as a musician-scholar.

When you expand your definition of research to include these four modalities, you can build strategies for your research-creation process. Knowing which modality you will employ can help you clarify your information needs and employ the right skills and techniques to meet your goals. In addition to thinking about how these modalities exist in your work, we invite you to add the concept of being a musician-scholar to your identity. Seeing yourself not simply as a musician, but a musician-scholar, prepares you to engage research-creation in any modality of your artistic work.

The four modalities Chapman and Sawchuk present are:

- Research-for-creation

- Research-from-creation

- Creative presentations of research

- Creation-as-research

Let’s dig a little deeper into understanding each of these modalities and how you might relate your own work to them.

Research-for-creation

“Students ask why it matters to study this. ‘Other people are studying that. I just want to play really well.’ We should all want to play well, but playing well can be significantly amplified by also doing research, and you can have this balance of both and they both inform each other.” Paula Maust

According to Chapman and Sawchuk, research-for-creation is the “gathering of materials, practices, technologies, collaborators, narratives, and theoretical frames that characterizes initial stages of creative work and occurs iteratively throughout a project.”[5]

This definition might seem obvious to many performing artists. We all do research on the sociohistoric context and theoretical analysis of music we are performing. In fact, there is a research discipline—dramaturgy—dedicated specifically to this work in live narrative art forms including musical theatre, nonmusical theatre, and opera.

Research-for-creation is generally the modality you will employ when you want to know more about an existing work that you are going to present. You are gathering sources to inform and enrich the creation of a performance. This modality often includes research skills and methodologies that feel very familiar to many musician-scholars: using scholarly resources to understand a relevant historical era or event; learning more about how a specific work fits into the overall catalog of a composer’s creative output; and reading and then applying existing scholarly analyses of works are all part of the research-for-creation mode.

“Research is studying anything that’s unknown to you and potentially finding something that is also unknown to others as well. So that you’re starting with this kind of question of wanting to know about something that you don’t know about. You’re starting to read and listen and explore various resources about that, and continuing to read and find out all that there is to know. Perhaps then stumbling onto a gap in the kind of general knowledge base and being able to uncover new information about a particular subject.” Paula Maust

Research-from-creation

“I had a huge misunderstanding about what music was. I never asked why music exists. Practice time took a lot, and I didn’t really question why I was doing it. I also didn’t question why I was playing European music when I’m obviously not European, right? Once I started asking those questions, I realized that I could approach music in a more holistic way. That it’s not about producing, it’s not about composing—it’s about communicating. Communicating through music, communicating with music, communicating with your peers, and making your ensemble members sound great, right? Because if we all sound great, and if we’re all working to make the other person sound great, we’ll all be great. So that’s an interesting parallel to society. But the main thing was that I did not understand the holistic nature of what music was, which today also encompasses the marketing and the commercialization of music.” Kyoko Kitamura

Chapman and Sawchuk define research-from-creation as “the extrapolation of theoretical, methodological, ethnographic, or other insights from creative processes, which are then looped back into the project that generated them.”[6]

If you ever wondered why a particular audience may have had a unique reaction to your work and decided to understand why, you have experienced the research-from-creation modality. Sawchuk and Chapman cite examples where creation of games or other art has created feedback data or produced other data sets that can then be used in other types of research. When user feedback from video game development informed new standards for engineers to deploy, that was an example of research-from-creation.

Research-from-creation can also be related to your practice in seemingly more practical ways. It can be important to be open to moments when you may want to think about opportunities to develop research-from-creation. For example, you might notice when you perform certain pieces of chamber music in nontraditional community settings, children from a certain age group all seem to have a shared response. This insight can help you place your observations in the context of existing research. Research-from-creation can also be purely musical: perhaps during a performance, you make a connection to other repertoire that you hadn’t made before. That may spur you to explore research about repertoire that leads to a deeper understanding of the music you’re performing.

Creative Presentations of Research

“Programming is a huge part of that thread in the relatability to programming. I have a fascination, at the moment, with the Schumann symphonies and his mental health. He utilized the symphonies through what I think is one of the most devastating stories of a man who dealt with such difficult mental health. I’m excited to talk to people at the World Health Organization, which is exploring this idea of loneliness and how music can actually be a sort of light out of the dark for people in society today. So being able to correlate Schumann symphonies to the idea of mental health is something that’s fascinating to me. That of course takes a lot of research—researching his letters, researching where he was when he wrote these things, what he was doing. The idea of programming and the relatability of a topic that might be pertinent to society today is another thread of why the research comes hand in hand with what I do on a daily basis.” Jonathon Heyward

Creative presentations of research might feel like a familiar modality to some performing artists, especially those who have done advanced study in college or university settings. These research-creation projects are defined as “alternative forms of research dissemination and knowledge mobilization linked to such projects.”[7] It can be tempting to say all creative presentations are the result of research. However, this modality differs from research-for-creation: Rather than informing a performance with research, the main goal in the creative presentation of research is for the performance to embody the results of your research in a non-traditional, perhaps unexpected way.

In fact, this is the modality that is most commonly used by nonprofessional or amateur musicians to communicate research findings that might have nothing to do with creative practices or performance at all. For example, Science, one of the most prestigious publishers in the physical and biological sciences, sponsors a contest called Dance Your Ph.D. every year.[8] The MAD Research Video Contest at Dartmouth College offers undergraduate students an opportunity to present their research in videos, allowing researchers to “be creative in a way that you can’t do in a written thesis, poster presentation, or formal talk.”[9] Harvard Law School made a musical entry in the Above the Law 7th Annual Law Revue contest that you can still view online.[10]

These expressions of research look to challenge the ways that scientific information is generally published and make it more accessible and interesting to new audiences. This modality is also being used by musician-scholars in powerful ways to present research-creation projects. One example is the dissertation work of A.D. Carson at Clemson University. Now a professor at the University of Virginia, Carson developed a 34-song album, Owning My Masters: The Rhetorics Of Rhymes & Revolutions, that presented his doctoral research.[11]

The emergence and acceptance of creative presentations of research at these and other forums has roots in all creative disciplines, including creative writing. Sawchuk and Chapman point out the limitations that traditional publication and dissemination systems have when making these kinds of works available.[12] However, scholars continue to assert space for these works through public performance and published artistic artifacts like albums, public art, and published music. You may need to look closely to identify these works because they are often not presented as research, despite containing research at the heart of their work. For example, Paul Rucker’s Proliferation does not call itself a research project, but the video installation is clearly a creative presentation of Rucker’s investigation of the U.S. prison system.[13]

The lack of acknowledgment of these works as research can present challenges for musician-scholars. Presenting these works as research may conflict with your artistic mission and your goals to communicate with your audience. Balancing your publishing, distribution, and communication around these projects can be critical in ensuring that your work can be understood by the audience you want to reach.

Creation-as-Research

“Sometimes the arts process looks messy, and you’re not quite sure where the end destination is. I have the knowledge to get children to the final destination determined by the test needs. Instead, I use research to find out what we don’t know. Let’s see where this journey is going to take us. What have we learned so far? What questions do we have? Let’s use research as a way to inform the kind of learning that’s born in the moment that comes from students’ genuine interest and curiosity, and that it’s still intentional. We’re still defining our goal, but we’re doing it collectively, and we’re doing it out of our own interest and based on what we discover together through our art making. I’m not always successful at doing that in the classroom, but I would love to see our educational norms and the way that classrooms are structured be challenged by investigating creative process types of teaching.” Christina Farrell

Creation-as-research draws from the other three modalities. It is a modality that brings to life the question “what is research” by exemplifying what happens when creative practitioners use teaching or performing opportunities as a laboratory, making research happen in real time.[14] As teaching artist Christina Farrell notes, it can also be an emergent collaborative process that happens between a musician-scholar and their audience or students.

Creation-as-research distinguishes itself from the other research methodologies by intertwining research and creative activities. This integration often results in a blend where the boundaries between research and creative processes are not always instantly clear or easy to distinguish.

These works can be most immediately recognized in instances of interdisciplinary exploration, particularly with technology. Oglala Lakȟóta artist and panel expert, Kite, demonstrates this modality in her work Pȟehíŋ kiŋ líla akhíšoke. (Her hair was heavy.).[15] With this work, Kite creates live performances with a 50-foot hair-braid computer interface. Kite describes the hair-braid interface as “something between an instrument and a sculpture.”[16] This system is comprised of “song, power, sound, processors, machine learning decisions, handmade circuitry, gold, silver, copper, aluminum, silicon, and fiberglass.”[17] In Pȟehíŋ Kiŋ Líla Akhíšoke, Kite uses the hair-braid interface to create an 8-minute work that embodies interaction between her physical performance and AI-generated texts. Kite situates this work in the ontology of her Lakȟóta heritage, stating “Lakȟóta ontology is an already established way of being, where seemingly ‘inanimate’ objects can be alive with spirit, and Pȟehíŋ kiŋ líla akhíšoke. (Her hair was heavy.) is an experiment in greeting that spirit.”[18]

For performing musicians, creation-as-research can happen in many ways that you haven’t even realized. Perhaps, as an early music practitioner, you want to explore what a composition would have sounded like in J. S. Bach’s time. You can research the kinds of spaces, acoustics, instruments, and tuning that players premiering his works would have used. The research results may seem to fit the research-for-creation mode. But in this example, the experiment doesn’t happen until you realize the performance in a space and recreate those specific aspects of performance. This is very different than researching the analysis of a piece to inform your performance choices. Creation-as-research is activated when you are making the performance itself a kind of research experiment.

For citizen artists engaged in educational programs, this can also be true. Perhaps, like the students in our story, you’re working with a public library to present music to a local community of children who immigrated with their families. You can do preparatory work ahead of time, but you won’t be able to assess and understand the impact of your work until the performance or educational interaction happens.

Every performance with Kite’s sculpture-instrument or each lesson Farrell presents in the classroom is an example of creation-as-research. Each creative researcher tests hypotheses about their instrument or teaching methodologies to inform future work.

Introducing Our Musician-Scholars

Meet our musician-scholars: Luis, Clara, Juliano, Hyo-Eun, and Sebastian.

Together, they are applying for a Peabody Career Development grant. Our musician-scholars are passionate about engaging children in diverse communities. They hope to create musical experiences that help children discover, appreciate, and understand different cultural backgrounds.

This project was inspired by their shared passion for music; performing together not only solidified their friendship but opened a path to learning about each other’s cultures.

Our group of musician-scholars wants to revisit the folk tales and folk songs of their respective cultures and re-imagine them for young audiences in the 1st through 3rd grades. They plan on sharing stories about characters, myths, and fables of their cultures, while updating them to reflect experiences that feel relevant to children today.

Their goal is three-fold:

- help children from multi-cultural backgrounds imagine themselves in the communities where they live,

- nourish children’s learning about the other cultures in their communities, and

- do so by using music as a story-telling vehicle.

This project involves composing five songs with narrated stories to be performed at public libraries in Baltimore City. They hope to share the performance materials online and create a blueprint for other musician-scholars to develop similar projects that are relevant to local communities.

They situate their research-creation situated in a research-for-creation modality.

1-2. Dig Deeper

Reflect on the four modalities of research-creation in your research journal.

- Which research-creation modality are you already incorporating into your artistic practice?

- Which research-creation modality do you want to explore to further your artistic mission?

The Research Spectrum

With over two decades of experience in the as librarians and educators, we have worked with many college students employing various research methods and methodologies. We have consistently observed that these students not only have shared assumptions of what constitutes research but also share a common expectation for a research process with distinct starting points, intermediate stages, and conclusions.

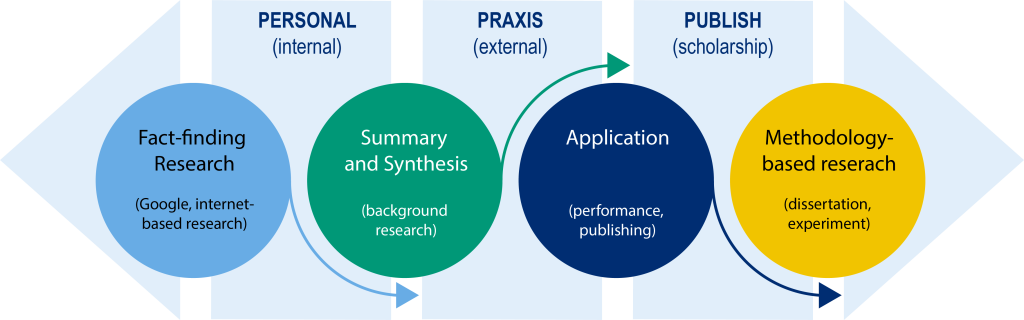

While that would help in defining a research plan, the research process is iterative. Research also encompasses both personal and private research, as well as praxis, where your research and learning are applied in practice. As a musician-scholar, you often navigate through this process subconsciously. Consider your studio lessons: When your instructor shares a technique, this is a form of citation, echoing what your instructor learned from their own teachers and the lineage of instructors preceding them. You then absorb, distill, and integrate this information and apply it to your performance praxis.

“As [a] classical violinist, just by learning from one person, I’m citing everybody that who taught them… People think they’re not doing research when they are—they’re already doing it.” Suzanne Kite

It’s important to realize that your research happens on a spectrum. At one end of this spectrum is the work that seems less formal: Googling a news article to verify a fact or ask an expert. At the other end is methodological research that may have formalized scholarly outputs. Much of your work as a creative researcher may happen in a space somewhere in the middle.

Leslie Ashbaugh, who was a cultural anthropologist at the University of Washington Bothell, often talked about how ordinary interactions can lead to research. In a class she co-taught with librarians on image analysis, Ashbaugh told an anecdote about how her research into beauty standards and advertising started while in line at the grocery store. There, looking at women’s magazines she observed how the cover and interior advertising affirmed a consistent set of beauty standards. This casual observation eventually led to a course that focused on visual communication in different cultures. You never know where seemingly minor research may lead you. It’s important to contextualize your research for yourself. Don’t underestimate the power and impact of the personal or less formal work you do; it can inform more formalized work later.

It’s also important to place the different parts of your research projects along this spectrum. If you are working on a research-for-creation project, the research will happen first. Your work will likely involve a mix of primary and secondary sources. You may never write a formal paper or give a lecture, but your discoveries may critically inform your performance and artistic choices.

The research-from-creation modality can be similar. Perhaps you will never formally share that research inspired by a creative experience, but it may provide launching points for new ideas, new projects, or even changes to your artistic mission. These first two modalities of research-creation may also form the basis of more formalized research projects. For music theory professor Paula Maust, one of our expert panelists, this process led her to develop Expanding the Music Theory Canon, a globally recognized website. An open-source collection of music theory examples by women and non-white composers, she has fully developed this research as a published book.[19]

By contrast, creative presentations of research can offer alternatives to more traditional modes of sharing your research. In this modality, you may be investigating the question you want to present and researching ways of engaging with this modality simultaneously. This can involve work at every point along the research spectrum. Strategically organizing those multiple lines of inquiry can help you develop an efficient but strategic research process.

The final modality, creation-as-research, happens in performance, but not without preparatory research. Your research process might entail developing a set of performance conditions or finding out how other researchers conducted and assessed similar projects. In this modality, preparing to document and assess the research that happens can be as important as the literature analysis you do before you conduct the research itself. It is also the modality where you need to be skilled in specific research methodologies that require training and disciplinary expertise.

Research can happen at any point in your creative process! It can also come from informal moments and interactions. It is critical to recognize when your work is research so that you can integrate that research into your performance plans.

1-3. Dig Deeper

Reflect on how your current research-creation work fits along the research spectrum in your research journal.

- What fact-based questions do you need to answer for yourself?

- What questions do you have that could be answered by summarizing and synthesizing reports or published scholarship?

- What research might inform you current repertoire, performances, or new compositions?

- List your current projects. Which modality of research-creation best describes these project? Which projects might you develop into formal, published, scholarship?

Conclusion

This chapter introduces musician-scholars to the value of research in their practice. To aid in developing research practices that integrate with artistic work, we present four modalities that can help you identify where research moments exist in your artistic work. These examples and insights gained from these four modalities of research-creation underscore the importance of integrating research into one’s artistic mission to amplify impact and engagement. As we prepare to delve into the information life cycle in the next chapter, we carry forward the understanding that research is not a static activity confined to scholarly publications, but a dynamic process that enriches our creative expressions and connects us more deeply with our communities and audiences.

Key Takeaways

Research is an important component to your artistic practice that furthers your artistic mission.

Embrace your identity as a musician-scholar and explore where research might be implicated in your research-creation projects.

Utilize the four modalities of research-creation to identify where research will be needed in your research-creation projects.

Position your research along the research spectrum, recognizing both informal and formal research activities and their relevance to your work.

Media Attributions

- Music Research concept © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Musician-scholars group © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Research Spectrum © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), “Read the Belmont Report,” Text, January 15, 2018, https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/read-the-belmont-report/index.html. ↵

- Zane Forshee, Christina Manceor, and Robin McGinness, The Path to Funding: The Artist's Guide to Building Your Audience, Generating Income, and Realizing Career Sustainability (The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University, 2022), https://pressbooks.pub/pathtofunding/. ↵

- Owen B. Chapman and Kim Sawchuk, “Research-Creation: Intervention, Analysis and ‘Family Resemblances,’” Canadian Journal of Communication 37, no. 1 (April 13, 2012), https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2012v37n1a2489. ↵

- Chapman and Sawchuk. ↵

- Chapman, Owen, and Kim Sawchuk. "Creation-as-Research: Critical Making in Complex Environments." RACAR: Revue d'art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 40, no. 1 (2015): 49-52. https://doi.org/10.7202/1032753ar. ↵

- Chapman, Owen, and Kim Sawchuk. "Creation-as-Research." https://doi.org/10.7202/1032753ar. ↵

- Chapman, Owen, and Kim Sawchuk. "Creation-as-Research." https://doi.org/10.7202/1032753ar. ↵

- “Official Rules for Dance Your Ph.D. Contest,” accessed January 29, 2024, https://www.science.org/content/page/official-rules-dance-your-ph-d-contest. ↵

- “MAD Research Video Contest,” accessed January 29, 2024, https://www.dartmouth.edu/library/mediactr/MADResearch.html. ↵

- Rather Read, 2015. https://vimeo.com/122237720. ↵

- Ashley Young and Michel Martin, “After Rapping His Dissertation, A.D. Carson Is UVa’s New Hip-Hop Professor,” NPR, July 15, 2017, sec. Music Interviews, https://www.npr.org/2017/07/15/537274235/after-rapping-his-dissertation-a-d-carson-is-uvas-new-hip-hop-professor. ↵

- Chapman, Owen, and Kim Sawchuk. "Creation-as-Research: Critical Making in Complex Environments." RACAR: Revue d'art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 40, no. 1 (2015): 49-52. https://doi.org/10.7202/1032753ar. ↵

- Proliferation - Paul Rucker - US Prisons, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySH-FgMljYo. ↵

- Chapman, Owen, and Kim Sawchuk. "Creation-as-Research." https://doi.org/10.7202/1032753ar ↵

- “Pȟehíŋ Kiŋ Líla Akhíšoke. (Her Hair Was Heavy.) (2019),” k i t e, accessed February 24, 2024, https://www.kitekitekitekite.com/portfolio/peh-ki-lla-akhoke-her-hair-was-heavy-2019. ↵

- Kite. ↵

- Kite ↵

- Kite ↵

- Maust, Paula. Expanding the Music Theory Canon: Inclusive Examples for Analysis from the Common Practice Period. Suny Press. 2023. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1410592666 ↵

a musician who has integrated research into their artistic identity and practices

a program that searches for and identifies items in a database that correspond to keywords or characters specified by the user, used especially for finding particular sites on the World Wide Web.

a process or order of computations that determines how search results or information is presented in an online search tool

a written expression of your current artistic goals and motivations

a research activity that can be associated with one or more methodologies

a systematic approach used by a discipline to conduct research

the process of having your scholarly article or book reviewed by academic peers that have expertise in the same field of research

research that includes performative or non-text creative aspects as the result, motivation, or methodology for the research itself (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

a lens or perspective that you are operating in when approaching your research project

a personal journal that you develop to document all stages of your research-creation project.

the gathering of materials, practices, technologies, collaborators, narratives, and theoretical frames that characterizes initial stages of creative work and occurs iteratively throughout a project (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

the study of elements and dramatic presentation of a work on the stage

the extrapolation of theoretical, methodological, ethnographic, or other insights from creative processes, which are then looped back into the project that generated them (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

an alternative form of research dissemination and knowledge mobilization linked to such projects (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

a process of challenging what constitutes research by making space for creative material and process-focused research-outcomes. (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

the philosophical practice of questioning what exists and what does not exist

an engagement with the ontological question of what constitutes research in order to make space for creative material and process-focused research-outcomes; draws from three other modalities of research

the act of putting theories or ideas into action or ready for external expressions