RESEARCH FOUNDATIONS

4 Preparing to Search

Kathleen DeLaurenti and Andrea I. Copland

Getting Ready to Search

It is important to understand the information life cycle and the kinds of resources available to you as a musician-scholar before you get started with your research-creation project. It is often tempting to open your favorite search engine and ask it questions the moment you have a research idea. While that works well when you want to know movie times, which musical performances are happening this weekend, or find a recipe, it can be frustrating when you take that same approach for your research-creation projects. In this chapter, we will focus on the search process and how to successfully plan a search strategy for a formal research-creation project.

The increasingly inclusive and interdisciplinary nature of music research means that in addition to collections of music sources such as scores, letters, and concert reviews, we must navigate multiple information systems across disciplines. It can seem intimidating and you might feel like you need to be an expert in disciplines outside of music. But you can develop flexible workflows and searching methods that allow you to bring expertise from multiple academic disciplines into your work.

To streamline your search process, begin by clearly identifying your information need. While a Google search might seem straightforward, fully understanding the questions you aim to explore often requires deeper reflection. Articulating your information need requires more than just posing a question to a search engine. You must thoroughly examine the need you identified; discern any underlying aspects; clearly define it in comprehensible terms; and then effectively translate this need for an information system.[1]

To gain a better understanding of your information need, ask yourself: What kind of information answers your questions? How will it serve as evidence in your argument or offer examples of what you want to understand? Then revisit the information life cycle to find where the resources that contain this information exists.

The development of your central research question is itself a significant information need. Yet, segmenting this central question into smaller, more manageable inquiries can enhance the efficiency of the research process. Consider the analogy of constructing a house: Trying to build without knowing how to frame a wall would be daunting. Similarly, tackling a complex research question without breaking it down into manageable tasks and questions can feel overwhelming. By addressing each component of your research question step by step, the process becomes more approachable and systematic, akin to building a house from the ground up with a clear blueprint.

In this process, it’s crucial to remain vigilant about potential biases in scholarship. Reflect on whose voices and narratives have been included and whose have been marginalized or excluded. Segmenting your approach to your research prevents you from being overwhelmed and prompts a critical evaluation of existing information sources, encouraging you to consider which perspectives are prioritized and which may be absent from existing scholarly discourse and information sources. By acknowledging and seeking out underrepresented perspectives, you contribute to a more equitable and comprehensive understanding of your subject matter.

As we move through this chapter, we’ll examine the history of search engines to better know how to utilize them in our search strategies. Once you know search engine basics, you can begin to look at your research question and practice developing a search strategy.

Why Is Searching Hard?

Before the year 2000, easy online access to research was something people dreamed about. Libraries have held card catalogs since the French Revolution.[2] For hundreds of years, these drawers of cards helped library users find information about every book in a library without having to aimlessly sort through the shelves, hoping to stumble upon the right book or musical score.

Libraries were early adopters of computer technology too. The first online library catalog was launched in the United States at the Ohio State University in 1976, long before many Americans had access to home computers.[3] As early as 1996, while Google was still a research project at Stanford University, Christina Borgman was critiquing the inadequacies of these early online search portals.[4] The first online catalogs required expert searchers who employed specialized terms and syntax to design a search to produce good results. While you could use online catalogs while sitting at a computer terminal, these catalogs generally reproduced the limitations of card catalogs. You could only search the same limited set of information about a book or article that you found on a card. Compared to Google’s ability to search every term on a website, this must seem like a profound limitation. Why didn’t library catalogs search every word in a book?

Today, it can be even more confusing to understand why library catalogs, research databases, and indexes as well as search engines such as Google, work differently. Musician-scholars who are still developing their research practice often want to rely on Google as their main search tool. And why not? Google doesn’t require a login, seems easy to use, and returns millions of results. Google was designed to make users feel comfortable with the tool so it could generate clicks and increase ad revenues, so it’s no surprise that many people use it as their go-to search tool. Although Google can be very useful for some kinds of research, it can make your research process take longer. One thing it does not do well is understand the purpose of your search. Google treats all searches the same, whether you’re trying to look up the weather or analyze a piece of music.

Unlike Google, specialized research tools, such as Music Index, the Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale, or Oxford Music Online, are built specifically to help researchers efficiently find the kind of music research-related evidence they need. These tools are not limited to music: Every academic discipline has developed tools to make searches easier that rely on terminology and methodologies in these fields. Understanding how to evaluate and choose a search tool and to use that knowledge to search effectively can help you expand your list of databases beyond Google and develop a more efficient process by going to the best search tool first.

Challenges with Searching

Hyo-Eun is working with Luis on the background research for their research-creation project. Getting started, she is feeling a little overwhelmed. With so many ideas to consider, she’s unsure how and where to begin. Hyo-Eun decides that thinking through the kinds of available search tools might be one way to organize her thoughts. She tried Googling her topic, but most of the results were just Wikipedia entries of information she already knows. Maybe there is another search tool that can help her find richer resources more quickly.

Understanding Search Tools

The homepage of your favorite search engine, whether it’s Google, Baidu, or Naver, is compelling. It promises to answer any question you ask! And in our daily lives, these tools can be incredibly powerful. With a few clicks, we can get directions to almost anywhere in the world, check movie times at local theaters, and serve up playlists and performances. However, search engines are not always the best place to start. Knowing which search tool to use with can help you find better resources more quickly and build a strategic, efficient search process.

Think about choosing a search tool the same way you think about shopping. If you need to stock up on necessities, a large chain grocery store will probably have what you need. You will find an impressive array of different kinds of food, staples, and cleaning supplies. However, if you need an ingredient to make a dish that is not available at your local grocery store, you may have to make a separate trip to a store that specializes in that kind of ingredient or cuisine. Specialty items may be harder to get where you live. Sometimes you might need to special order them online from another state or country.

Gathering information sources should prompt the same kind of choices. Google serves as a convenient general store. It tries to fulfill a wide range of needs, but it probably lacks the depth or nuance required to pinpoint results that precisely match your research needs. On the other hand, libraries provide access to a selection of search tools that, while potentially more challenging to locate and use, reward your efforts with richer and more relevant materials, just like high-quality ingredients enhance a gourmet dish.

Let’s examine four kinds of search tools to understand their differences and benefits: search engines, research databases, indexes, and the library catalog.

Search Engines

A search engine is an online search tool that crawls the open internet for information gleaned from websites. Search engines were probably the first search tool you ever learned how to use. Today, Google is one of the most popular, but it’s not the only one. Others, like Bing, Naver, and Baidu, are also commonly used. While it’s tempting to think that all information on the internet is available through a search engine, that’s unfortunately not true. Information provided by subscriber-only online services may be missed by a search engine or blocked altogether. Websites can even include computer code that prevents search engines from gleaning their content.

Search engines in the United States are commercial enterprises. They generate profits from advertisements embedded in their search results and on user-generated content platforms that they may own. This profit motive incentivizes these companies to make design decisions about how the search engine works that maximize profits.

For example, Google owns YouTube. As a content creator, you may generate revenue from ads placed on your original content that you post to YouTube. Recent data shows that as of 2016, Google keeps $45 for every $100 generated from content that you post on YouTube.[5] Google has an economic incentive to ensure you’re happy with your search results, so you may not have realized that there are other factors that influence the development of the tool. However, Google also has an incentive to display search results in a way that maximizes ad revenue for companies that buy ads. That doesn’t mean that Google allows companies to pay for higher results, but this profit motive can lead to things like prioritizing e-commerce results where advertisers are relying on a return on the investment from their advertising dollars. In music, that means that search results such as links to streaming, merchandise, or tickets will likely appear at the top of the list.

Search engines also search the full text of any website that will allow them to crawl the site, including the metadata. This means a search engine can use all the information about that website and all the information published there to determine whether it ranks high or low in search results. Collecting this information also impacts the way Google processes your search terms.

Google’s search algorithms are designed to perform fuzzy searches, which means they go beyond the exact words or phrases entered in the search bar. These algorithms compare your search terms with a range of common and related terms to broaden the scope of the search. A fuzzy search can be advantageous when you are unsure of the correct terminology or if you’re using colloquial or outdated language. However, fuzzy searches can become a hindrance when your search is for something specific.

For instance, if you’re looking for a baker who sells quality dessert pies, Google will likely return results for any dessert-related establishment, which is only helpful if the best pies can be found at a local bakery rather than a dedicated pie shop. If Google’s search algorithm assumes you will be happy with any dessert, you will receive more results. The algorithm also assumes those additional options are helpful.

Conversely, searching for the term cookies in Google with the intent of finding information about digital tracking cookies may lead you to a long list of local bakery listings instead of the technical insights you need about cookies that track web activity. Because Google is generally going to prefer e-commerce activities, even though it has both kinds of cookies indexed in its search engine, the algorithm will assume you want to order some chocolate chip cookies and not research web technology. Sometimes a search engine’s assumptions about your needs can complicate rather than simplify your quest for information.

Comparing Google and Google Scholar Results

Even within different Google tools, search can behave differently. As an example, we can search for the K-pop group BTS (Bangtan Sonyeondan/방탄소년단) on Google’s homepage to see what kind of results it presents. The search results offer background information from the band’s website, Wikipedia articles, and links to other K-pop fan sites. Google also provides links to band members’ social media and points to official services, like Spotify and YouTube. As we scroll down the page, we will start to see profiles and articles from magazines like Teen Vogue and news sites like CNN. Further down the list of results, websites focused on K-pop gossip sites and tabloids proliferate.

Therefore, the question arises: What’s missing? The current search results don’t offer insights into BTS’ popularity or analytical perspectives on their music. They also don’t provide research related to BTS’ fan engagement strategies, merchandising, or role as diplomatic envoys to the United Nations. Most search engines can easily furnish information about the band members, their most popular songs, and ways to purchase merchandise—which, incidentally, generates ad revenue for Google—but simple a Google search fails as tools for in-depth research.

However, a search with Google Scholar results in pages of scholars in different disciplines who have explored some of the in-depth research topics posed above. You might wonder why these results are separated. While we don’t know for sure, it’s likely because academic publishers are not buying Google ads. Adding Google Scholar results to the main search engine would lead to fewer people clicking on profitable ads—Google’s primary source of revenue. While it does aspire to be the best general search engine, every change to your first page of results is designed to make more revenue for Google and its ad partners.

Google excels at providing foundational knowledge and background information on a topic, yet its effectiveness diminishes when delving into more specialized research. It can be disappointing when a tool you use every day falls short in meeting your research needs. However, later in this chapter, we explore strategies to maximize Google’s utility for research purposes, ensuring you get the most out of its capabilities.

4-1. Dig Deeper

Try searching your favorite artist or musician on Google.

- Do the top results provide background information, retail or ad-supported media, or scholarly information?

- What differences do you notice when searching for the same artist in Google Scholar?

Research Databases

A research database is a resource that organizes a set of materials that you can query through a search. Research databases generally collect a set of scholarly articles or books by academic discipline or publisher. These tools can be expensive and may only offer subscriptions to libraries and academic institutions. Sometimes they’ll allow Google Scholar to index their metadata so that you have the option of purchasing a single scholarly article, but that can be expensive. Prices generally range from $29.99 to $49.99 per article. For those lucky enough to have subscriber access, these databases do search the full text as well as the metadata. This explains why your search terms can appear in the body of the article, the title, or the abstract.

Unlike Google’s search engine, Google Scholar works much less like a search engine and more like an academic database. It has a narrowly defined scope limited to scholarly articles, federal court decisions, and patents. Rather than trying to answer any question by looking at information on every web page, Google Scholar is focused on results from academic publishers and open-access repositories.

When we search for BTS in JSTOR, we find around 10,000 scholarly articles, book chapters, and research reports. By default, JSTOR presents the sources it deems most useful first, like Google. Searching by date reveals the oldest resources are from 1923, which are not relevant to our search, since BTS has only been active since 2013—a gap of nearly a century. We also get results in more than 40 languages, including English. But because the authors have access to many JSTOR collections, we find results in many subjects beyond music. Unlike Google’s results—which include dynamic websites, static online articles, and multimedia—the kinds of resources you find in JSTOR mirror the resources researchers used in print before the advent of the internet.

4-2. Dig Deeper

Practice evaluating different search tools. Search JSTOR for your favorite artist.

- How do search results on JSTOR differ from search results on Google?

- How does it compare to a Google Scholar search?

- Does JSTOR let you fully sort and view search results without a subscription log in? What kind of information about JSTOR results can you learn without paid access?

- Check your local library to see if they provide subscription access to JSTOR. What are the different ways that JSTOR and Google Scholar allow you to filter or sort your search results?

Indexes

Indexes can be the most difficult resource to understand, but they remain an incredibly important resource to access research that is not available in a digital format. While historical research may not be important for particle physicists or medical researchers who need cutting-edge information to do their work, performing artists and musicians can benefit from reading research from the 20th century still under copyright. (Copyright is covered in more detail in Part II: Copyright Essentials.) Even when copyright is not an issue, many resources are only available in print. For example, at the Peabody Institute, the Filby Rare Book Room has 2,320 rare books. Nearly all of them are in the public domain and could be freely available online. However, to date, only 244 items in that collection have been found to be digitally available online—only 10.5% of the collection!

Indexes can help fill the gap when we want to find published research that may not be available in a database. The Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale (RILM) is an index for musicians and performing artists. It covers music research from all disciplinary perspectives from more than 2,400 scholarly journals. But even RILM can only provide full-text access to a small number of titles: 260 scholarly journals are available for full-text searching.

How did this happen? Who would digitize titles and abstracts from scholarly articles without digitizing the articles? For indexes, this is generally because they also existed in print; migrating that print index to digital was easy when research tools began to be published online. Digitizing, correcting, and hosting full-text of older scholarly articles was a time intensive and expensive venture. You can still view older print indexes of RILM online at the Internet Archive with a free account. When they were only available in print, these indexes were updated and distributed to academic libraries two to four times each year. Indexers were hired to scour scholarly journals and compile any information about any new music research to include in the index. Library users would then work with librarians to find the scholarly articles they needed or borrow them from another library.

Today, nearly all scholarly journals are published and accessed online. However, moving an entire industry online didn’t happen overnight and many older publications have not been made fully available online for researchers. In the early days of online research, it was easier to move the indexes online than it was for some publications to fully publish online. Because of this limitation, indexes are still prevalent in many libraries and remain useful for finding older research that may not be online yet. It can be frustrating to find a source that looks relevant to your research, only to realize that you now have to figure out how to access the full text. Keep in mind that distributing a copyrighted work is something that only the copyright holder can do. This means that indexes can be easier to maintain and add to because it doesn’t require permission from the copyright holder to list a title in index. By contrast, putting a full text online does require permission from the copyright holder.

But, don’t let that discourage you! Indexes are curated by experts in specific academic disciplines who compile high-quality source lists. If you are having trouble locating a book, full-text article, or other source listed in an index, remember that librarians are always available to help you access it. They can work with you to borrow materials from other libraries or publishers to ensure you have the information needed for your research.

Unlike JSTOR and Google Scholar, these indexes rarely allow the public to search them without a subscription. However, nearly all college or university libraries in the United States welcome members of the public to use these resources when they visit the library in person. Publishers may not make subscriptions available that allow these libraries to share access remotely for researchers who are not students, faculty, or staff. In Chapter 10: Publishing and Accessing Information, we share strategies for researching that outline some of the ways you can do this work without an institutional affiliation.

4-3. Dig Deeper

Practice evaluating online indexes. Navigate to your local library website. In the research database section, check for access to Music Index or the Music Periodicals Database.

Search this index for your favorite artist.

- What kinds of resources do you see in the search results?

- Are you able to access the full-text of these resources?

- How does the index compare to your Google Scholar search?

Note: Indexes are generally available by subscription access only. However, some print versions of indexes, like RILM, have been digitized for access online.

The Library Catalog

Do not to ignore the library as a search tool. Library search continues to improve and make it more seamless to search specialty resources such as research databases and discipline-specific indexes at the same time you search the library collection. But the core function of a library catalog is to provide access to the library’s curated collection of resources designed to best suit the library community’s needs. That means that a local municipally-funded public library holds different resources than a university such as the Johns Hopkins University.

The library catalog attempts to do a lot of things that Google or indexes cannot. A library catalog tries to provide the most relevant resources based on metadata available for physical and digital collections, like CDs, DVDs, books, and scholarly journals. In addition to searching metadata about all the physical items on the shelves, the library also has some full-text scholarly articles and books available electronically that it can search word for word. This distinction is important because it means you might need multiple search strategies to find all the best resources in the library catalog. If you want to find all the books about K-pop in a library, and some of them were only about BTS and did not mention K-pop in the description about the book, those books about BTS might not appear in that library catalog search about K-pop.

Physical items in the library are also coded with a specific kind of metadata called the Library of Congress Subject Headings, a very large but limited list of official terms that all libraries in the U.S. use to make it easier to find books on similar topics. However, because LCSH is an official list, it can be slow to change and reflect the kind of resources in library collections. There are terms for popular music, rap, and hip hop, but there is no official term for K-pop!

The library catalog strives to provide good access to many kinds of information resources—sometimes too many. Even though it includes search results from specialized indexes and research databases, you may notice that it isn’t always the best place to find these resources. Research databases or indexes that only provide access to one kind of scholarly article can use specific kinds of metadata to take advantage of the resources’ similarities. These search tools create powerful, specialized search terminology that doesn’t have to adhere to the LCSH rules. For example, even though there isn’t an LCSH term for K-pop that helps you find all the K-pop books, recordings, and scholarly articles in the library catalog, Music Index has a term for “K-pop” that easily helps you find all the articles, book reviews, and books that it indexes on the topic. Because the Music Index terms aren’t linked to LCSH in the library catalog, limiting your targeted strategic searching to the library catalog risks providing you with incomplete results. So even if your library includes everything from Music Index in the catalog search results, it might still be faster to take the time to log in directly to Music Index, identify the subjects that they use related to your research question, and then add them to your search to get to better results more quickly.

One of the most powerful library catalogs available for universal use is WorldCat. It contains information on the physical and, in some cases, digital collections of member libraries around the world. In Baltimore, you can locate resources ranging from nearby Washington, D.C., or as far away as Australia. If something is only available in Australia, your local libraries will make every effort to assist you in obtaining access to that resource, typically at no cost.

4-4. Dig Deeper

Practice evaluating different library catalogs. Remember, your local library is building a collection primarily for researchers and library users in your community. WorldCat is trying to provide a catalog that includes collections of libraries from around the world.

Search for your favorite musician in your local library and WorldCat.

- What kinds resources do you see in your search results?

- How do those results reflect the different catalogs?

- What ways do these catalogs allow you to filter or sort your searches?

- How does searching the library catalog differ from searching JSTOR or Google Scholar?

Artificial Intelligence

At the time of writing this book, artificial intelligence (AI) has only begun to be implemented in search. Early attempts to create good AI search have resulted in hallucinations with services like ChatGPT returning citations to sources that don’t exist. Google has attempted to incorporate AI into its search algorithm, too. However, part of Google’s algorithm relies on personalizing things for you based on previous searches or other information it may collect about you. Search engines incorporating AI that rely on personalization have been observed returning poor search results. Google has been observed providing results that list websites that provide weak evidence to answer a question or providing different evidence for different users who asked Google the same question. Always evaluate a new search tool: each of the characteristics we describe for the other search tools and the exercises presented here are designed to help you build skills to evaluate these sources, understand their benefits and limitations, and make good choices.

As AI continues to be integrated in each of these search tools, it’s important to continue to evaluate a tool’s benefits and limitations. You may also want to do a Google audit of your privacy settings to ensure that Google isn’t over-personalizing results. Personalization of algorithms can lead to algorithms noticing and responding to your implicit and explicit biases and preferences, which can make it hard to hear a diverse set of voices in your research. This can be especially harmful when you have research questions where information only exists on the very early parts of the information life cycle, like social media, news sources, and other primary sources. Personalization can sometimes prevent you from finding information sources from the past week, month, or year on topics where you might be trying to get outside your information bubble.

Preparing Your Search Shopping List

Now that we have explored what is behind different online search engines, you may feel overwhelmed about where to start your search. But spending a few minutes to connect your information need to what you know about different search tools can make your search process more efficient.

| Type of Source | Available As | Search Tool |

| Primary sources | Diaries, letters, and autobiographies | Library catalog |

| Primary sources | News reports | Newspaper-specific database, like ProQuest Newspapers |

| Primary sources | Personal papers, photos, and ephemera | Archival collections |

| Secondary sources | Scholarly articles | Interdisciplinary databases, like Google Scholar or JSTOR, and specialized databases, like RILM or Music Index |

| Secondary sources | Scholarly books | Library catalog, Google Books |

| Tertiary sources | Subject encyclopedias | Library catalog |

Use this search strategy planner to organize your search process.

One reason efficiency matters is that research is iterative. You might start your information gathering and have trouble finding appropriate resources and start again. Or you might find some really great resources that introduce you to a new idea or concept that inspires you to shift your inquiry in a different direction. You should expect this to be a part of your research process when you get started—plan accordingly!

This can happen at any time during your research process. You might start a research project about BTS and realize while you are collecting background information that New Jeans would be a more interesting K-pop group to study. Or, you may have gathered many resources about BTS and their fandom, but finding a source about how the fandom organizes philanthropic projects related to the group inspires you to narrow your search and investigate if this is true with other K-pop groups as well. Remaining open to your curiosity during this process allows you the intellectual freedom to make changes that ensure the research aspects of your research-creation work evolve in line with your artistic mission.

Compiling Research Ideas on Your Shopping List

Material in this section adapted from Forshee, Zane, Christina Manceor, and Robin McGinness. “Project Ideas” in The Path to Funding: The Artist’s Guide to Building Your Audience, Generating Income, and Realizing Career Sustainability. The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University, 2022. https://pressbooks.pub/pathtofunding/. Adapted under a CC-BY 4.0 license.

At this point in your research process, you’ve already done a lot of work before even doing one search for information. You now know how to map different kinds of information sources on the information life cycle; how they can be used as primary, secondary, or tertiary sources; and which search tools will be the most useful for you based on the specific kinds of evidence you need.

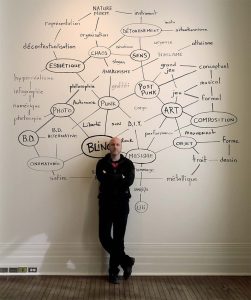

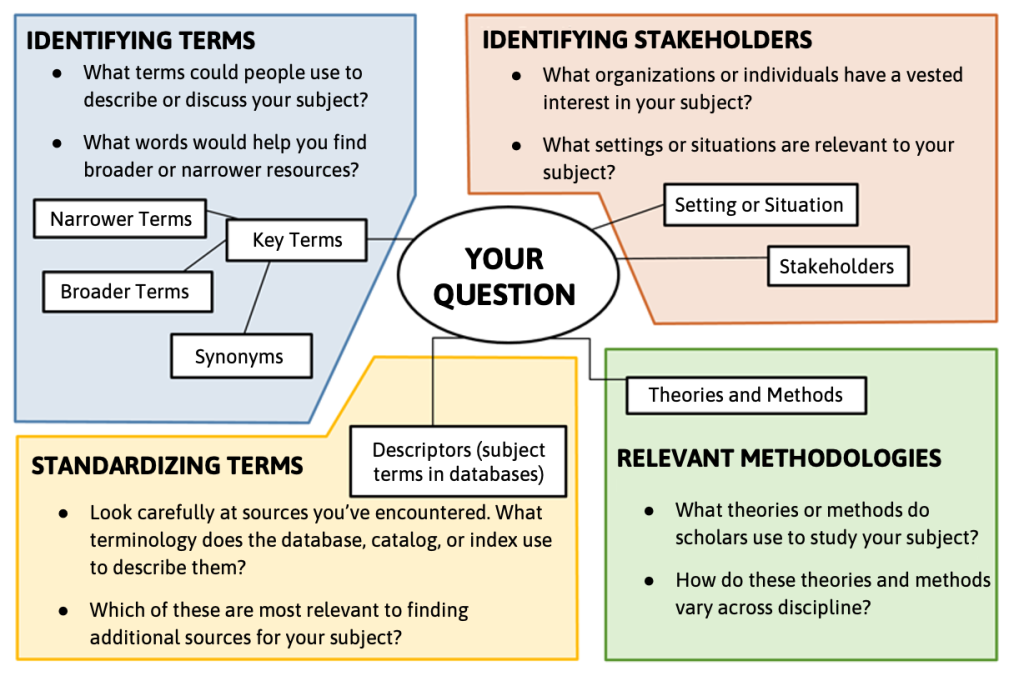

But you may have already run into challenges trying to share your ideas with search tools. Computers don’t speak English, Spanish, Mandarin, or Korean—they store information digitally, in sequences of ones and zeros. While new technology is constantly trying to bridge this translation gap, using a mind map will help you translate your research questions into language that search tools understand. A mind map captures ideas visually, organizes them in a hierarchical manner, and discovers relationships among disparate ideas in your information needs.

Mind maps typically emerge from a single concept placed at the center of a page that is then used as a vehicle to generate material for potential solutions to a problem or a challenge.[6] In The Path to Funding, the authors present mind maps as tools to help you generate project ideas. But project ideas can also be thought of as the beginning of your research-creation. You can break down any part of your research-creation project to create a specific mind map to help plan your search strategy.

The following example shows how to map terminology around an area of inquiry for your creative research:

Breaking Down Your Research Topic

Hyo-Eun and Luis have inventoried their resources and know which research databases and indexes they can access in addition to Google. But because they are collecting resources about the cultural background of every member in their group, they need this process to be strategic and efficient. Hyo-Eun and Luis decide to make some mind maps to discover any shared concepts and ideas and then use the results to plan their search process.

Hyo-Eun and Luis have inventoried their resources and know which research databases and indexes they can access in addition to Google. But because they are collecting resources about the cultural background of every member in their group, they need this process to be strategic and efficient. Hyo-Eun and Luis decide to make some mind maps to discover any shared concepts and ideas and then use the results to plan their search process.

They know they are interested in folk tales and folk songs from a number of different cultures. But Hyo-Eun and Luis also want to better understand what makes music meaningful to audiences, especially their target audience of 7- to 10-year olds. They know the mind map process will help crystalize their ideas and approaches

Why Should You Use Mind Mapping?

This process of idea generation, or ideation, allows you to rapidly develop possibilities. The more ideas that you might want to explore, the greater the chances of creating a better idea, project, or design. This is true with creative research too. Earlier in the chapter we examined how research is iterative. When mind mapping for research, you will start to map out the different questions related to your research idea. Sometimes, the first iteration of your mind map can end up looking like a connected map of different research questions. Once you have those questions, you can organize those ideas to apply in a research context.

Making a Research Mind Map

Mind mapping relies on the free association of words, allowing all possible ideas to come to the surface. As a visual and tactile process, a mind map can stimulate a wider range of connections. You can also use the process to map onto search tools and build a strategy to make your time searching as impactful and efficient as possible.

The process of mind mapping works to overcome your inner critic and ensures you capture a lot of ideas about how you view your research. Considering the terminology that appears in your initial brainstorming can also help you identify implicit biases that you hold that you can then interrogate in your research-creation project. Once you have these terms and have challenged yourself to think of different ways researchers may have articulated these same ideas, interrogate how your experiences may have shaped the default choices you made. How might someone with a different voice or set of experiences name the same ideas?

Mapping and Mining Ideas

Effective mind mapping for research-creation requires you to map your ideas and then mine them to build effective search strategies. When you start your mind map, you are just trying to see what ideas feel most relevant to your research-creation. Use software or go analog with a pen and paper to create your mind map. Butcher paper, a flattened-out paper bag, or a chalkboard are all great options. Use what’s available and allows you to make the largest, wildest map of your ideas.

Follow these steps for creating a mind map.[7]

- Choose a central research question (exploring the potential).

- Generate possibilities (creating layers).

- Identifying key concepts (mining the ideas).

Step 1: Choose an Idea (Exploring the Potential)

Start with a question or challenge that’s related to your project and place it at the center of what will become your mind map.

Step 2: Generate Possibilities (Creating Layers)

- Draw three to five lines that extend off the central point you’re interested in exploring. If you’ve circled your main idea at the center of your page, the image might begin to look like a drawing of the sun.

- Set a timer for 2 to 3 minutes. Giving yourself a time constraint keeps you from censoring your ideas. Go for quantity, not quality.

- Write down single words, short phrases, and ideas. They can be wild, far-fetched, or beyond what might be feasible.

- Now repeat this process by building on the first round of ideas you generated. Continue to repeat the process until you have two to three layers of word associations.

Giving yourself too much time can draw the process out, resulting in self-censoring and fussy editing. By contrast, a time constraint forces you to generate options in just a few minutes.

Step 3: Identify Key Concepts (Mining the Ideas)

This is where it gets interesting! Review your mind map for keywords, phrases, and ideas that excite you. These are going to help you create a search strategy for your research mind map that you can use with any of the search tools we’ve discussed.

Once you’ve mapped your initial terms in your research mind map, it’s OK to take a little more time interrogating which kinds of bias might be unintentionally appearing in your map.

- In your keywords quadrant, are your identifying terms inclusive? Do they include terms that might be used both within and outside of the communities or music that you want to know more about?

- When you look at who’s represented in the Identifying Stakeholders quadrant, are there any voices missing that should be represented in your inquiries?

- Thinking back to common methodologies in music, what are the possible benefits or pitfalls of the methodologies you identified? Are there any kinds of new methodologies, like action heritage that might be missing? How might new and old methodologies work together?

You might be uncertain about database terms. Start with words or specific concepts that are familiar to you. You can collect additional terms as you search by looking at results in each search tool and identifying any subject terms, subject headings, or keywords associated with your top results. While every corner of this map can grow and change throughout your search process, the search tools terms will always be responsive to your findings.

Conclusion

Preparing for a research-creation project demands a thoughtful approach to gathering information. It begins with understanding the information life cycle and identifying the kinds of sources that will best support your inquiry. By articulating your information needs clearly and considering the array of search tools available, you position yourself for a more effective and efficient search process. This approach not only streamlines your search but also enriches the quality of your research by encouraging you to explore diverse perspectives and methodologies.

Remember, the aim is not just to accumulate information but to engage deeply with your topic, recognizing biases, and striving for a comprehensive understanding. As you move forward, let the principles discussed guide your exploration, knowing that each step is part of a larger journey in your research-creation project. In the next chapter, we focus on how put everything together, from identifying the perfect search tool to creating dynamic search queries.

Key Takeaways

Clearly articulate your research questions and information needs before starting any search. Spending time preparing to search helps you develop strategic and efficient search processes.

Break down complex research questions into smaller, more manageable inquiries to find the most relevant sources and avoid collecting resources that aren’t relevant.

Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different search tools, such as Google, specialized databases, and library catalogs. Assessing search tool strategically is important in developing efficient research processes.

Create mind maps to translate research-creation questions into search-friendly keywords and concepts. Mapping your ideas visually can help you see relationships between ideas and translate those ideas into language that search tools will understand.

Interrogate your research mind map for potential biases and identify places on your map where you can add inclusive terminology and methodologies to your search.

Stay informed about developments in search engines such as AI-powered search tools. Regularly evaluate AI-generated results for relevance and accuracy.

Remember that research is an iterative process. Be prepared to adjust your search strategy as you discover new insights.

Media Attributions

- Music Research concept © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Breaking Down Your Research Project © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Mind maps © Stella Purdue is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Research Mind map adapted by Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Robert S. Taylor, “The Process of Asking Questions,” American Documentation 13, no. 4 (1962): 391–96, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.5090130405. ↵

- The Library of Congress, The Card Catalog: Books, Cards, and Literary Treasures (Chronicle Books, 2017). ↵

- Christine L. Borgman, “Why Are Online Catalogs Still Hard to Use?,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 47, no. 7 (1996): 493–503, https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199607)47:7<493::AID-ASI3>3.0.CO;2-P. ↵

- Borgman. ↵

- Werner Geyser, “How Much Do YouTubers Make? - A YouTuber’s Pocket Guide [Calculator],” Influencer Marketing Hub, November 27, 2016, https://influencermarketinghub.com/how-much-do-youtubers-make/. ↵

- “Idea Generation - Techniques, Tools, Examples, Sources And Activities,” Alcor Fund (blog), accessed December 5, 2023, https://alcorfund.com/insight/idea-generation-2/. ↵

- Kent State Office of Online and Continuing Education, “Assignment Type: Mind Maps,” September 2011, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10734-010-9387-6. ↵

a map that demonstrates how publishing influences the way information is shared over time.

a published or unpublished source of information in any media or format that helps to address your information need

a musician who has integrated research into their artistic identity and practices

research that includes performative or non-text creative aspects as the result, motivation, or methodology for the research itself (see Chapman and Sawchuck)

a program that searches for and identifies items in a database that correspond to keywords or characters specified by the user, used especially for finding particular sites on the World Wide Web.

a recognition that you need information to answer a question. information needs occur in daily life and research practices

the set of cards arranged by title, author, or subject that helped users find books on the shelf in a library before online catalogs were developed

an organized list of materials that has been curated by an organization, often libraries, for access by their community; catalogs point to information sources that might be available in a physical space or online

a collection of research resources and their associated metadata that is organized for search and access

a list of articles or other publications within a discipline or topic; provides bibliographic information such as author(s), title, where it was published, and sometimes abstracts

the act of collecting information about websites for the purpose of creating a searchable set of data

a set of data that describes and gives information about other data; for example the title of a book is a piece of metadata

a process or order of computations that determines how search results or information is presented in an online search tool

the use of an algorithm to search which is not literal and may return results based on likely relevance even though search terms and spellings may not be an exact match

a piece of data from that a website stores on your computer that the website can retrieve at a later time

a list of specific subject terms managed by the Library of Congress that are applied to books, movies, and music in library catalogs in the United States and allow you to find all materials on a subject in a library

a term currently used to describe tools based on large language models that respond to natural language questions with text, image, or media-based responses

a term used to describe the phenomenon of large language models like ChatGPT returning incorrect information

a written expression of your current artistic goals and motivations

a diagram used to visually organize information into a hierarchy, showing relationships among pieces of the whole; It is often created around a single concept, drawn as an image in the center of a blank page, to which associated representations of ideas such as images, words and parts of words are added.