PUBLISHING PRACTICES

10 Publishing and Accessing Information

Kathleen DeLaurenti

One of the great promises of the internet was that information could be widely accessible to everyone at low or no cost. Anyone seeking knowledge could learn from low-cost but high-quality online resources. And while it may seem that everything is and has always been online, much of the 1,000-year publishing history of printed musical scores, scholarly journals, and scholarly books remains available only in libraries and archives.

In addition to making the vast history of human knowledge available online, the competing interests of publishers, authors, and consumers seem to be more at odds now than ever. Unlike the print environment, the digital environment works on technologies that make sharing easy. This change has been welcomed by consumers, but is a concern for publishers and some creators who worry that digital piracy will undermine their business model.

One ongoing development is the move to stop selling born-digital media to consumers and libraries. Concerned that digital content cannot be easily controlled, large publishers of books, music scores, and sound recordings continue to move to a leasing model. While this eases publisher concerns around piracy, it means that increasingly no one (including libraries) can collect and lend books or sound recordings.[1] At the same time, individual musicians and authors are embracing new technology; they are leveraging our connected information world to develop collaborative models for publishing that favor artistic control and building relationships with their audiences.[2]

Libraries, researchers, and creators are asking challenging questions as the future landscape for knowledge production and dissemination evolves:

- Who should own digital books, scores, or sound recordings?

- How do we maintain a record of our cultural history when libraries cannot collect books, articles, or sound recordings?

- What role should creators have in deciding how their work is published and shared with their audience?

- What is the value of collecting when digital media is platform dependent and publishers can modify or delete the content on those platforms at any time?

- What will the future of memory institutions or private collections be if publishers and copyright holders prevent individuals and institutions from preserving these resources for future generations of scholars?

Scholarly Publishing

Much like learning copyright basics, understanding some basics about publishing can help you understand the intersections between published works, copyright, and access to resources. Knowing how works are published can even help you understand how they’re organized online or in catalogs. As we discussed in Chapter 4: Preparing to Search, the kinds of search tools we have are a reflection of the way historical publishing practices have been adapted to online environments over time. For many, an ideal world wouldn’t even have online indexes: we would simply have digitized access to all knowledge created through human history.

In many ways, today’s online information environment specifically reflects Western European publishing practices. The first scholarly journals in Western Europe date back to the 17th Century.[3] However, in China, a burgeoning publishing industry was active as early as 1030, when the government adopted block printing technology to distribute Confucian teachings widely.[4] While publishing industries across the globe evolved differently, today, a scholarly publishing system that centers European traditions has become dominant. This includes a peer-review process that has not changed much since 1731, when the Royal Society of Edinburgh published the first peer-reviewed scholarly journal Medical Essays and Observations.[5]

In 1880, Elsevier became the first for-profit publisher of scholarly journals.[6] Throughout the 20th century, the dominance of Western European scholarly publishing grew as publishers like Elsevier expanded in tandem with investments in research universities.

At this time, publishing involved significant labor and time. We can clearly see the time and labor investments in the traditional information life cycle: Newspapers with short articles that only required editorial review appeared first. Then came scholarly articles that required additional time in the publishing process for peer-review. Eventually, scholarly books that represent larger intellectual undertakings with longer review processes emerged. Before Wikipedia, you couldn’t see a topic in an encyclopedia until enough scholarly articles and books had been published to deem it worthy of inclusion. Even today, Wikipedia’s own editorial guidelines require content to be cited by published secondary sources, to be included on the website.

Before the advent of online publishing, publishers managed every aspect of the publication process except writing the actual scholarship and providing peer-reviews. Publishers had editorial boards that managed the process of selecting scholars who would peer-review the scholarly articles submitted by other scholars in their field. These peer-reviewers pointed out limitations to experiments; suggested other research that scholars should incorporate into their work; and made recommendations to the editors about whether the scholarship was good enough to publish. Publishers also hired designers, printers, and copy editors who made sure that these publications were error-free and ready for distribution. Scholarly articles were published together in issues that were sent to individual scholarly society members or subscribing libraries where they were available to researchers on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis.

There was immense financial, labor, and time costs to this process. Scholarly articles were sent by mail to editors for consideration who then mailed them to peer-reviewers. The editors had to wait for those reviews to come back through the mail and return them to authors for revision. This process kept pace with technology, moving from handwriting to typewriters to computers. But in the early history of publishing, publishers had to make significant investments to cover the costs of postage, typesetting, and printing of these issues.

By the early 2000s, most publishers began moving their publications online and distributing articles in the portable document format, or PDF. In 2004, Google tried to index these publications hosted on scholarly publisher websites with a new tool called Google Scholar. With the launch of Google Scholar and publisher supported research databases and indexes, researchers no longer had to engage with an issue of a scholarly journal to access a single article. This is so common today that most novice researchers equate scholarly articles with PDFs because they have never interacted with them in any other format.

Understanding that scholarship was not always created as PDFs or posted on websites can be an important part of your research strategy. Accessing scholarly articles as single PDFs doesn’t change the fact that each article is part of an issue that comprises a volume of a scholarly journal. In Chapter 4: Preparing to Search, we examine many different search tools. Understanding the relationship between a scholarly article, an issue, a volume, and a scholarly journal will also help you understand what you should expect to find when using these search tools. For example, Music Index, which indexes articles across hundreds of publications from different publishers, is generally a digital representation of a print index and may not have PDFs of the articles you want to read. On the other end of the spectrum, Oxford University Press’ online database does include full-text content, but only from journals published by Oxford University Press. Knowing that you can find full text of Oxford scholarly journals on their platform can make finding an article you want to read easy. But Music Index is a better tool when you want to survey published scholarly articles across a topic that may have been published over time by a number of different publishers.

When you find yourself confused about which format a source might be available in or why you’re not finding it online in an index or database where you expected it to be, here’s what to do: Simplify your search process by stepping back to think through how it was originally made available and where a copyright holder or archive might continue to provide access.

Open Access

Traditionally, publishers charged subscription fees to cover the labor and materials necessary to publish print books and scholarly articles. Throughout history, scholars have provided peer-review services as well as their books and journal articles to publishers for free. Scholars are motivated to do this because it advances research in their field and demonstrates the value of their scholarship, an important part of securing tenure at a college or university. Profits have never been an important motivator for scholarly publishing. Historically, the fees for subscriptions have been paid by libraries motivated to ensure that researchers, students, and staff can read what other scholars are publishing.

Because scholars provide their work to publishers for free, you might think that a move to digital-only publishing and distribution platforms would become less expensive for scholars and libraries. In fact, many novice musician-scholars assume that publishers take advantage of the internet to make all of their published research available online for free.

However, as the University of California at San Francisco notes, costs of access to health sciences scholarly journals have increased by 87.5% since 2013.[7] These costs have profound impacts to you as a musician-scholar and what you might access online. Wealthier institutions can provide more research access to their students and researchers.

This can mean longer wait times for students and researchers at smaller institutions. It can sometimes mean no access at all for independent musician-scholars. The University of Colorado-Boulder reports that an annual subscription to journals from the publisher Wiley costs more than buying a 92-foot luxury yacht.[8] This means that few public libraries are able to provide these resources to their communities.

In 2001, a group of scholars who wanted to take advantage of the internet to share scholarship more quickly and freely met in Budapest to discuss how to make this a reality through open access publishing practices. This resulted in the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI).[9] This declaration was an important step that scholars took toward asserting that the research they freely contributed to the world should also be freely accessible to everyone. It was also the first time that open access was defined, declaring it was “economically feasible, that it gives readers extraordinary power to find and make use of relevant literature, and that it gives authors and their works vast and measurable new visibility, readership, and impact.”[10]

Since the BOAI, scholars, libraries, and some publishers have been working together to identify ways to make more research open access. Many libraries now have institutional repositories where scholars can post fully edited versions of their work for students and their peers to access for free. Some libraries and publishers, including Project MUSE, are working together on new subscription models to make work openly accessible.[11] There are also open access initiatives driven by the European Union and the United States. Most recently, the President of the United States instructed the Office of Science, Technology, and Policy (OSTP) to work with all federal agencies that fund research to formulate policies that would require all federally funded data and research to be made open access the first day of publication.[12] This is critical in making more research accessible: in 2021, 55% of research in colleges and universities in the U.S. was funded by taxpayers in the form of federal grants.[13]

Expanding Your Research-Creation

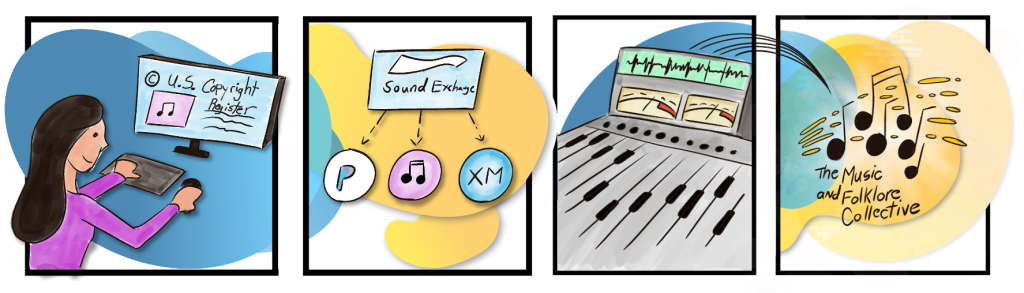

Research-creation projects often extend beyond a single performance or information need. Luis has been passionate about finding opportunities for their project to have an impact beyond Baltimore City audiences. Clara agrees and suggests that she and Juliano can continue to explore the copyright issues related to sharing the group’s work online.

Research-creation projects often extend beyond a single performance or information need. Luis has been passionate about finding opportunities for their project to have an impact beyond Baltimore City audiences. Clara agrees and suggests that she and Juliano can continue to explore the copyright issues related to sharing the group’s work online.

Inspired by the idea of open education resources (OER), they decide to use this opportunity to create a new OER. Sharing is at the heart of their project, so OER seems like a good vehicle to share their work while allowing others to build on it and contribute additional cultural perspectives.

Our musician-scholars hope to make their folk song arrangements, translations of the text into multiple languages, and images that they commissioned as part of the project website.

Open Education

Open access is a model that generally focuses on publishing and sharing scholarly articles. But the textbooks that many musician-scholars rely on for their learning have also seen price increases that have made it hard for some students to afford required course materials. In fact, 66% of students skip buying at least one textbook every semester while in college.[14] However, faculty are increasingly identifying ways to help learn that doesn’t require spending hundreds of dollars on textbooks.

This book is an example of an open educational resource (OER), and more specifically, an open textbook. When faculty assign open textbooks, students have access to them on the first day of class, and faculty can customize material to support their curriculum. Instead of assigning a textbook that costs $200 and only using 30–50% of the contents, professors can ensure that the assigned materials support their preferred teaching strategies so that students have the best learning experience.

Other open education practices extend beyond just textbooks and can also include open pedagogy, where students take part in creating learning materials for an external audience. In courses where faculty and students create new resources together, students may be asked to participate in making decisions about everything from the platform used to distribute resources to the licensing terms applied to them.

Many musician-scholars include some kind of teaching in their career plans. Knowing about OERs can help you make decisions about what to use in your own curriculum and guide how you might develop resources to share. Many colleges and universities will even incentivize the development of OERs by providing faculty with stipends or grants to fund their creation.

The complex licensing scheme that allows Spotify or YouTube to legally share large catalogs of music for free can seem like a kind of open access. But in OER publishing models, the goal is to compensate an author or creator at the beginning of a project so that no licenses or royalties need to be collected after the work is published. These works are also generally released with an open license such as Creative Commons, that promotes resharing, remixing, and reusing without needing permission from the copyright holder.

While freemium streaming models provide free access, they are not true open publishing platforms. Open publishing is starting to take shape in some musician-scholar communities for noncommercial research-creation projects. Projects like Handel for All and All of Bach aim to make video performances of the composers’ full catalogs available in high-quality versions online. The Public Domain Song Anthology presents over 300 standards from the Great American Songbook in Real Book style with traditional and modern harmonization. More research-focused resources developed for scholars, such as the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe: Digitized Version, are also becoming more commonly available online for researchers.

These open projects are attracting musician-scholars who want to change the systems of compensation for their work while making it easier for audiences to experience and use their work in other research-creation projects.

Research After Graduation

After graduation, many students are stunned at the number of paywalls they run into when trying to do basic research. Everything from a new analysis of a Chopin nocturne to new medical breakthroughs may be more difficult to read without paying a fee. Some people find themselves relying on pirate sites like Sci Hub[15] and LibraryGenesis.[16] However, there are resources you can use as an independent musician-scholar to unlock scholarly publications legally to continue to incorporate scholarly research in your research-creation projects.

Your Library

You may think of your local library as the place you went to borrow picture books as a child. Aside from children’s books you can often find research databases, language learning systems, and wealth of research material for reference. These resources can be especially useful for locally focused research-creation projects to better understand your community. Your local library will also offer interlibrary loan services that will borrow materials from other libraries on your behalf so that you can access important research that you need.

You may also have access to some research databases as an alumnus from your college or university. Make sure to check with your alumni office to find out.

Browser Extensions

Here are two important resources you can add to your browser to find the version of an article stuck behind a paywall. First, you can try the Open Access Button, which will try to find an open access version of a paywalled article. If it can’t find it, the Open Access Button will contact the authors and ask them to make it openly available for researchers like you. Next, you might try Unpaywall, a database of nearly 50 million open-access versions of scholarly articles. The browser extension shows you a green unlock button when there is an open-access version of an article you want.

As we mentioned in Chapter 5: Practical Search Strategies, Zotero is a useful tool for managing your own collection of research resources. You can use the Zotero browser extension to add resources to your Zotero library where you can organize, annotate, and generate bibliographies.

In addition to these two tools, musician-scholars often find themselves looking for information from websites. Sometimes those websites might be taken down, moved, or changed over time. If you ever find yourself needing to uncover what a website looked like on a specific date or period of time, the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine opens a window into the internet’s past.

Open Education Repositories

Many open educational resources are housed in repositories at colleges and universities or on publishing platforms like Pressbooks (where this book is hosted!). You might also find OERs on Worldcat.org, the library catalog. However, sometimes you want to search specifically for OERs and aren’t sure which resources you can trust.

George Mason’s OER Metafinder searches across popular OER collections including OER Commons, OASIS, MERLOT, and OpenStax. These collections offer resources at the K-12 and college level materials. OASIS includes not just OER, but other open access books from scholarly publishers in 115 different collections.

Books

Sometimes you just need an old-fashioned book to help you with your research. If the book you want isn’t published as open access, there are still some options to get what you need.

Google Books searches the full text of millions of books and provides access to short snippets. Sometimes when you only need to verify a fact or cite some very specific evidence, Google Books is enough. And don’t forget to scroll down on the “Get the Book” section—if you need the full text, it can tell you the nearest library that has the book.

Collections of open access books are also growing. The Directory of Open Access Books (DOAB) provides access to more than 78,000 open access books in every discipline. Books hosted on their OAPEN platform include useful annotation tools that can help your analysis and summary work. University Presses are also making more information openly accessible. Project MUSE, an initiative of the Johns Hopkins University, hosts open access books and scholarly journals. MIT Press and the University of Michigan Press also support robust open access book programs. However, finding individual open access books can be challenging; projects like the DOAB attempt make that easier by creating a catalog where you can search these offerings in one place.

The Internet Archive’s Open Library can provide access to electronic versions of physical books that were never published as e-books. It also can help you find books it doesn’t have in full text through Worldcat.org so that you can get them at the library closest to you. Additionally, the Internet Archive and the HathiTrust Digital Library provide access for those with visual impairments who may need adaptive technology to access books that are not available online from the publishers. The Internet Archive also host a number of music collections including the Great 78 project, Live Music Archive, the Free Music Archive of musician contributed audio, and the DATPIFF Hip-Hop mixtape archives.

While it might seem hard to believe there could be an information desert in 2023, for musician-scholars who are struggling to find materials without access to a large research library, it can be a frustrating experience. The tools mentioned above provide free and legal access to important research and teaching collections that you can use long after your university library card expires. And remember, if you live near a college or university, you may also be able to go there in person to use the collections, even if you can’t access them from your couch.

Breaking Down Your Research Topic

While Luis and Hyo-Eun were researching history and finding primary sources, they ran into some challenges. Some of the books they wanted to consult were at other libraries and they weren’t sure if it would be worthwhile to request them through interlibrary loan. What if the books came and weren’t useful?

While Luis and Hyo-Eun were researching history and finding primary sources, they ran into some challenges. Some of the books they wanted to consult were at other libraries and they weren’t sure if it would be worthwhile to request them through interlibrary loan. What if the books came and weren’t useful?

Luis and Hyo-Eun soon learned that previews in Google Books and the Open Library let them examine these books to decide whether to request them for further research. This step saved them time in their research process.

In addition, they found recordings they wanted to study, but were at inaccessible archives outside of Baltimore. Juliano suggested looking at the Great 78 project. They were excited to find early recordings of some of the project’s folk songs. The Great 78 Project’s online collection of early 78 rpm disks offered ideas and insight into how these folk songs were performed and shared in the early 20th century.

Conclusion

This chapter covers the dynamic and ever-changing publishing landscape of the digital age. From traditional print media to today’s digital landscape, musician-scholars face a myriad of challenges and opportunities in their research process. The transition to digital knowledge production has not only reshaped how knowledge is disseminated but also how it is accessed.

Our next focus will be on the critical task of successfully publishing your creative work. This requires a keen understanding of legal issues, ethical considerations, and publishing practices. This requires a keen understanding of the legal issues, ethical considerations, and publishing practices. In the next chapter, we begin to understand how the foundational knowledge we’ve explored can be applied in producing and sharing your research-creation projects.

Key Takeaways

The long history of publishing scholarship in music and other disciplines extends back 1,000 years and covers formats from oral traditions to print materials to digital environments. Understanding this history aids in navigating online and and physical research environments.

Support open access initiatives to promote free and widespread availability of scholarly work. This can involve contributing to institutional repositories or supporting initiatives that make scholarly work freely accessible.

Utilize and contribute to open educational resources(OER) to enhance learning and teaching experiences. This includes adopting open textbooks and participating in open pedagogy projects.

Anticipate the challenges of accessing scholarly materials as an independent researcher. Familiarize yourself with tools such as browser extensions, open education repositories, and alternative sources including Google Books and the Internet Archive for continued access to research materials.

Media Attributions

- Publishing concept © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Using Copyrighted Works © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Breaking Down Your Research Topic © Peabody Institute is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- “The Anti-Ownership Ebook Economy,” accessed November 7, 2023, https://nyuengelberg.org/outputs/the-anti-ownership-ebook-economy/. ↵

- “About the Brick House Cooperative,” The Brick House Cooperative, accessed November 7, 2023, https://thebrick.house/who-we-are/. ↵

- “Scholarly Publishing: A Brief History | AJE,” accessed November 7, 2023, https://www.aje.com/arc/scholarly-publishing-brief-history/. ↵

- “出版史_百度百科,” accessed November 27, 2023, https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%87%BA%E7%89%88%E5%8F%B2/12771008. ↵

- “Scholarly Publishing.” ↵

- “Elsevier,” in Wikipedia, October 24, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Elsevier&oldid=1181714029. ↵

- “Journals Cost How Much?,” UCSF Library (blog), accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.library.ucsf.edu/about/subscriptions/journals-costs/. ↵

- “Quiz: How Much Do CU Boulder Libraries Subscription Resources Cost?,” University Libraries, September 30, 2020, https://www.colorado.edu/libraries/2020/09/30/quiz-how-much-do-cu-boulder-libraries-subscription-resources-cost. ↵

- “Budapest Open Access Initiative,” accessed November 27, 2023, https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/. ↵

- “Budapest Open Access Initiative.” ↵

- “Project MUSE,” accessed December 12, 2023, https://about.muse.jhu.edu/muse/s2o/. ↵

- The White House, “Memorandum on Restoring Trust in Government Through Scientific Integrity and Evidence-Based Policymaking,” The White House, January 27, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/memorandum-on-restoring-trust-in-government-through-scientific-integrity-and-evidence-based-policymaking/. ↵

- “Universities Report Largest Growth in Federally Funded R&D Expenditures since FY 2011 | NSF - National Science Foundation,” accessed February 19, 2024, https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf23303. ↵

- Cailyn Nagle and Kaitlyn Vitez, “Fixing-the-Broken-Textbook-Market,” June 2020. https://pirg.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Fixing-the-Broken-Textbook-Market_June-2020_v2-5.pdf. ↵

- Press Release, “Electronic Frontier Foundation to Present Annual EFF Awards to Alexandra Asanovna Elbakyan, Library Freedom Project, and Signal Foundation,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, July 26, 2023, https://www.eff.org/press/releases/electronic-frontier-foundation-present-annual-eff-awards-alexandra-asanovna-elbakyan. ↵

- Blake Brittain and Blake Brittain, “Textbook Publishers Sue ‘shadow Library’ Library Genesis over Pirated Books,” Reuters, September 14, 2023, sec. Litigation, https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/textbook-publishers-sue-shadow-library-library-genesis-over-pirated-books-2023-09-14/. ↵

a published or unpublished source of information in any media or format that helps to address your information need

a journal published regularly that includes scholarly articles in a specific field of research; they are also referred to as peer-reviewed or academic journals

a book that is peer-reviewed and published by a scholarly press primarily for an academic audience

an organized list of materials that has been curated by an organization, often libraries, for access by their community; catalogs point to information sources that might be available in a physical space or online

a list of articles or other publications within a discipline or topic; provides bibliographic information such as author(s), title, where it was published, and sometimes abstracts

the process of having your scholarly article or book reviewed by academic peers that have expertise in the same field of research

a map that demonstrates how publishing influences the way information is shared over time.

an article published in a scholarly journal that has been peer-reviewed; also often called a peer-reviewed or academic article

an information source, typically a scholarly book or scholarly article, that analyzes primary sources or empirical data

a group of experts that manage review and publication of scholarly books or articles for a scholarly journal or publisher

a collection of research resources and their associated metadata that is organized for search and access

the person, company, or organization that owns the exclusive rights to a copyrighted work

archive as a verb is the practice of collecting, arranging, and preserving materials in libraries, archives, and museums. an archive can also describe a place where this activity happens that provides access to material in person and online

a musician who has integrated research into their artistic identity and practices

a term that describes scholarly publications that are freely available to the public

any textbook or learning material that is made available under an open license that allows instructors and learners to retain, reuse, remix, revise, and redistribute the material

a textbook that is freely available for instructors and students to retain, reuse, remix, revise, and redistribute

the teaching and learning practices that leverage open, participatory tools to enable collaborative, open learning experiences that often produce open educational resources

an approach to teaching that allows students learn by creating teaching or other educational materials that are designed to be freely available to a public audience

the payment you receive for a licensed use of your copyrighted musical work or sound recording

any type of license that allows for different kinds of reuse, remixing, or redistributing.

an organization that manages an international set of licenses that allow a copyright holder to determine what users can do with a copyrighted work without seeking permission

the phenomenon of trying to access an information source that can only be viewed, listened to, or interacted with after paying a fee

a website that hosts information sources without permission from the copyright holder

a system used by libraries to allow users at one library to request items that are in the collection of another library

a small application that is designed to be added to a specific browser; popular information-focused extensions include tools to find open access versions of articles, privacy extensions to protect your privacy, and ad blocking extensions

a publisher that specializes in publishing scholarly journals or books

software or hardware that is designed to help persons with disabilities access digital content