5 Trade: Development, Growth, and Inequality

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Identify and understand the leading trade theories of Import Substitution Industrialization and Export Led Industrialization and their effects on development.

- Understand the history of how countries used these trade theories to grow their economies, specifically through integration with Global Value Chains.

- Identify other modes of development outside of Import Substitution Industrialization and Export Led Industrialization and how states use these.

- Understand the scope of research still needed when it comes to trade policy and its effects on development and inequality.

Introduction

The leading theories among economists tend to show that most countries benefit from free trade. This movement towards free trade, meaning less barriers such as tariffs and other requirements on imports/exports, is called trade liberalization. Organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Trade Organization (WTO), and the World Bank are all organizations with a consistent goal of increasing trade liberalization around the world, as well as encouraging policies that lead to freer trade. Advocates of open trade policy argue that trade is essential as countries that engage in international trade experience rapid growth, innovation, and productivity. The theory of comparative advantage, which simply means that a nation should choose to produce goods which it can produce at a lower opportunity cost and more efficiently as compared to other nations. When nations start to specialize this can lead to rapid economic growth which in turn generates more income, a variety of goods and services for consumers, and more opportunities for workers. Essentially, efforts to integrate with the global economy through trade policy drives economic growth and reduces poverty locally as well as across the globe. While this widely supported argument for international trade presents it as an optimal policy especially for economic growth and development, the application of free trade policies is far more complex than it is suggested to be.

However, the understanding of economic theory has evolved over the centuries. Early on, the dominant theory was mercantilism from the 16th to the 18th century, that a country’s exports should exceed its imports with the trade surplus being used to expand reserves of gold or silver. Then British economist, David Ricardo proposed the theory of comparative advantage which emphasizes efficiency in production, and still holds today. Ricardo argued that even if a country can produce goods more cheaply than other nations, it can still benefit from trade. And lastly, contradicting earlier theory, the American economist Frank William Taussig coined the concept “terms of trade” which defines the ratio between the number of exports needed to acquire a certain number of imports. The theory of terms of trade indicates that the smaller the ratio, the better as the terms of trade can change in ways that either benefit or harm the country through a reduction in welfare. Second, the nature of trade has also drastically evolved as it no longer occurs between small producers but among global or multinational corporations who produce and sell goods and services globally. Although this was the result of trade liberalization and advanced technology, international trade has grown far more rapidly than global economic growth, impacting the types of strategies developing countries use to stimulate economic growth (Kirst, The Wilson Center).

This chapter will first discuss two prominent trade theories, Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) and Export Led Industrialization (ELI) exploring their emergence, importance, and limitations. The study of ISI and ELI will showcase whether developing countries may, in fact, be disadvantaged if they liberalize their trade regimes. Next, as a direct application of these trade theories, this chapter provides a case study of South Korea and its use of ELI to promote economic growth as well as Brazil and its use of ISI. Section 2 expands upon the ISI and ELI strategies to consider other ways countries can develop by examining total factor productivity, Global Value Chains (GVCs), and terms of trade. To conclude, the final section explores the future of research since it remains obscure as to how trade policy contributes to growth, namely its effect on inequality. Additionally, new research has suggested that much of the original thinking behind how trade policy affects development may in fact be misunderstood.

Trade Theories: Import Substitution and Export Led Industrialization

In the 1930s and 1940s, as a result of the Great Depression, countries began focusing on domestic manufacturing since the loss of traditional export markets required more domestically-oriented, protectionist economic policies. And following World War II, trade policies were influenced by the belief that the key to economic development was the creation of a strong manufacturing sector. To do that, developing countries needed to protect their domestic manufacturers from international competition. This trend was prevalent and reflected in trade policies as domestic groups chose to consciously limit foreign competition, seeking to become more self-sufficient through the industrialization of their domestic market.

Import Substitution Industrialization

ISI is a trade and economic policy that was established based on the idea that countries, specifically developing countries, should utilize the local production of industrialized products to reduce their dependence on developed states (Manger and Shadlen, 2015). At its core, ISI seeks to replace imports with domestic production. Policies are enacted by developing countries to create an internal market, seeking economic development by encouraging domestic investment. ISI policies include high barriers to trade, government subsidies and incentives to industry, and may include state ownership of much of the economy. Tariffs and nontariff measures worked to shield local producers from international competition. Investment in industry was encouraged by subsidies and tax incentives by the government. Countries that had high levels of state ownership in their key sectors were able to provide important inputs to local firms. Preferential treatment of domestic firms in government procurement was often used as a tool to promote local industry. By pursuing protectionist, domestically oriented trade policies, a country can shore up production channels for each stage of a product’s development (Manger and Shadlen, 2015). Imposing local content requirements on foreign investors ensures transnational firms locally source their inputs, increasing domestic demand. This targets newly formed domestic industries to fully develop sectors so that production can be competitive with imported goods. At the same time, strategic sectors are reserved outright for domestic firms. Therefore, it is important to understand that ISI is not just about protecting domestic firms, but also about creating incentives for investment in new sectors of production.

While ISI policies have been successful in some cases, there are limitations to the concept. The attempts of ISI policies to promote domestic production often required large commitments of capital goods as well as advanced technology that had not been available domestically (Manger and Shadlen, 2015). These products would have to be imported, leading to negative balance-of-payment issues. This required more foreign borrowing or massive government spending. Even for the infant industries that ISI often focused on, development policies were not necessarily successful in the long term. For industries where policies were successful, there were issues when the infant industries needed to become subject to market forces but did not want to lose the government assistance. Generally, these issues meant that government finances deteriorated, external debts grew, and ISI policies generated inflationary pressure. That all meant that there was a shift in economic development and trade policies. The debt crises in the 1980s meant that protectionist strategies became unsustainable. Therefore, developing countries shifted towards new strategies of economic development in the 1980s and 1990s that were based on more liberalized trade and export orientation (Manger and Shadlen, 2015).

ISI Case Study: Brazil

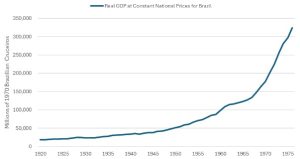

Brazil implemented an industrialization strategy of import substitution from 1930 to 1980. There were numerous industrial policy tools being used, and the central state had considerable control over a wide range of economic factors and prices. It actively invested in basic industry and infrastructure, making up more than 40% of all investments made in the economy. An increase in total factor productivity allowed for the development and creation of a compounded industrial structure. More specifically, sufficient institutions, and infrastructure within the terms of this accepted economic theory were the key to Brazil’s industrial rise.

ISI focuses on the preservation and fostering of newly developed local industries in order to completely develop new sectors and make domestically produced goods competitive with imports. With Brazil, the role of immigrants was fundamental for the expansion of the coffee industry, but perhaps even more so for the development of Brazilian industry overall. From the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, immigrants were brought in and ‘provided’ by the government for the manufacturing industry and for the establishment of free laborers. Understanding the growth of Brazilian industry depends on how coffee production has changed in terms of accumulating and the emergence of a wage-earning class as opposed to slaves or small-scale farmers. The influx of immigrants from Europe, particularly Italy, had a considerable impact on the growth of production, as well as on Brazilians who started earning a living. Wages would have been greater if the growth of the coffee business had been entirely dependent on European immigrants. Exports were the main engine of economic growth in Brazil, increasing by 214% between 1840 and 1890. The five-fold growth in coffee production suggested that the coffee industry was the main economic driver despite sugar expanding by 33% and cotton by 43%.

Between 1928 and 1955, the manufacturing industry expanded at an average annual rate of 6.3%, increasing from 12.5% to 20% of GDP. The establishment of new financial institutions created during the ISI era was a significant development in Brazil. The increase of American investment during the 1920s marked a significant change, which persisted throughout the 1930s with the manufacturing plants and factories in Brazil. Brazil did not have many export costs because the US was the country to which most of its products, including coffee, were sent. This was simply the period of transition from Brazilian proprietors of coffee plantations to more industrialized economies.

Export Led Industrialization

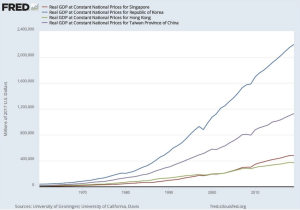

ELI focuses on the growth of manufacturing production aimed at the international market. By exporting goods that a nation has a comparative advantage in, developing countries can speed up their industrialization process. By reducing tariff barriers, establishing a fixed exchange rate, and increasing government support for exporting sectors, markets become open to foreign competition and gain market access to other countries (Karunaratne, 1980). Around 1970-1980, many nations began to adopt this model which gave them huge benefits and helped to accelerate their economy. This type of economic policy is an excellent method to increase the exports of the country which improves the country’s foreign currency, and a higher export growth can generate higher productivity, thus creating even more exports in a positive upward-spiraling cycle. A big example is the well-known East Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong). They utilized ELI policies and thus experienced rapid economic growth. While they never had free trade, they implemented many trade policies that were less mercantilist and were meant to promote exports (Manger and Shadlen, 2015).

The East Asian Tigers faced much less competition from other developing countries and therefore were able to achieve rapid growth for their export-oriented industries. Further, there were aspects common between all four countries that allowed for their development to be more successful while it may differ in other countries. For example, the success of a particular development strategy may depend on external conditions, such as the different forms of foreign aid and financing available to a country. Figure 2 shows the increase in GDP of the East Asian Tigers from 1960-2018. This explains very clear the rapid growth in the economy of those countries because of the changes in their economic policies. The four East Asian Tigers being the first developing countries to pursue an export demand growth process at an early stage in the postwar era: this is especially significant as these countries were among the few that would eventually achieve a high level of manufacturing exports as a percentage of total exports, 134.5 percent for Hong Kong in 2010 and 37.9 percent for South Korea.

The main difference between export-led industrialization and import substitution industrialization is the extent to which industrial production is targeted for export rather than domestic competition. ISI is about reducing trade and emphasize protectionist policies while ELI is about stimulating trade with policies that promote international trade. Countries that used infant industry protection initially, but then turned those industries into global competitors, were more successful in the long haul (Manger and Shadlen, 2015).

ELI Case Study: South Korea

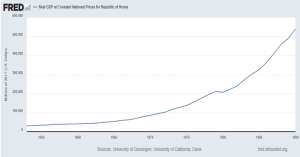

South Korea, one of the Asian Tigers, using ELI policies was able to promote rapid economic growth and therefore, serves as a comprehensive case study to examine the success of ELI discussed in the previous section. After experiencing a military coup in 1961, South Korea was one of several East Asian countries which began experimenting with the export-led industrialization (ELI) model of trade policies. This primarily included the restriction on imports into the country but combined with the focus on selling manufactured goods to its trade partners, including the United States and Japan. The exploitation of cheap industrial labor, due to a lack of regulation on labor, allowed South Korea to boisterously expand their economy until the early 1980s. They are, however, quite a special case due to the amount of foreign loans received from its major trading partners, a benefit not shared with most other countries which utilized ELI.

To prioritize the exporting of goods in the national economy, South Korea was required to change the focus of its manufacturing industries, from their initial import-substitution position to the more outwardly focused ELI system (Haggard et al, 1991). This largely involved the direct regulation of these industries, including hefty tax credits and institutional support for exporting industries. While investment in the domestic market was still common during this period, protections for companies which chose to focus on exports were prioritized by the regime, to signal their attempt to change to an export-oriented market (Haggard et al, 1991). South Korea also began limiting its imports, chiefly focusing on the importation of raw materials and capital goods (Krishnan, 1985). This was a major shift from the import-intensive economy of South Korea during the mid-to-late-1950s. Limiting imports to only the necessary materials for industrialization allowed South Korea to optimize their industrialization, often exporting consumer goods to the same countries the raw materials were acquired from.

South Korea’s success using export-led industrialization policies stemmed largely from its relationship with much larger economies, most notably the United States and Japan (Krishnan, 1985). After establishing a permanent military presence in South Korea, to protect its own interests, the United States and Japan quickly became the largest purchasers of South Korean exports, with an average of over 35% of all exports from South Korea being purchased by the United States between 1961-1982 (Krishnan, 1985). This was also reciprocated by South Korea, with Japan and the United States respectively accounting for the first and second-highest share of South Korea’s limited imports (Krishnan, 1985). These relationships between the United States, Japan and South Korea catalyzed the steady growth of South Korea’s economy during the industrialization period. Both the U.S. and Japan are also responsible for providing direct aid to South Korea, with over $5 billion in both public and private loans over this time period provided by the United States alone (Krishnan, 1985). Japan, which did not provide any major assistance until 1965, was able to account for almost 20% of South Korea’s private loans, providing $3 billion of the $13.79 billion in commercial loans between 1959-1978 (Krishnan, 1985). Without the trade and loans generated by South Korea’s largest trading partners, it likely would not have been able to see the rapid rate of growth it enjoyed until the 1980s. Investments from large corporations helped the growth of the economy. Those corporations took advantage of the commercial opening to diversify exports to have more manufacturing exports or natural resources, with greater incorporation of technologies and knowledge.

Arguably the most important factor in the success of the export-led industrialization system in South Korea was the abundance of cheap labor. Following the Korean War, workers’ rights legislation such as the Labor Standards Act, Labor Union Act, and Labor Disputes Adjustment Act were ratified (Minns, 2001). These legislations gave laborers the guarantee of an eight-hour workday and the ability to form workers’ unions. Under the military regime established with the coup in 1961, these labor unions were antagonized, which included banning said unions from political action and collaboration with other unions (Minns, 2001). No further developments were made in the realm of workers’ rights legislation until the passage of the Minimum Wage Act in 1986. Due to these conditions, South Korean manufacturers were able to take advantage of the low-cost labor, rapidly increasing their rate of industrialization (Krishnan, 1985). This abundance of labor was optimal for the manufacturing of consumer goods, such as electronics and footwear, as well as textiles, metals, and goods which are further manufactured by the importing country to create finished products (Krishnan, 1985). Countries with higher labor costs, such as the United States, were keen to take advantage of trade with South Korea for their cheap labor. This allowed South Korea to rapidly expand their exports after adopting the ELI model, contributing to the steady economic growth seen by the country using this model.

While South Korea’s economy was able to flourish by using the ELI model, it was assisted heavily by both foreign loans and trade with its major partners, the United States and Japan. Despite this, South Korea was able to develop a large economy due to its primary focus on international trade. Use of the ELI model allowed South Korea to expand from a small, postcolonial economy with a focus on industrialization for the domestic market, into one more export-oriented, able to fare well on the stage of global trade.

Supplemental Development Strategies

Numerous countries such as South Korea, analyzed in the previous section, have utilized ELI and ISI strategies to successfully engage in international trade. However, there are other strategies that countries employ to stimulate economic development including but not limited to total factor productivity, global value chain integration, national savings, terms of trade, and immiserizing growth.

Global Value Chains

Global Value Chains (GVCs) and the integration of more and more countries into them started to dominate global trade in the 1990s. Global Value Chains simply refers to the idea that one product may be produced with products that come from all around the world. For example, an American made car might also have parts from Japan, Taiwan, and the Netherlands despite being made in the United States. Dunhaupt and Herr define GVCs as “a product crosses borders several times until it is finished, or a finished product is assembled in one country using many intermediate products produced in different countries” (Dunhaupt et. al 2021). Intermediate goods are any goods that are used to produce other goods, including knowledge, training and more, which are an especially important component of GVCs. Many developing countries took advantage of specializing in these intermediate goods and gearing trade policy towards greater integration into GVCs and the global economy.

The theory of comparative advantage is essential to understanding how and why countries are striving for greater GVC integration. Comparative advantage means that a country will specialize in what it “is best at”. For example, if a Chinese factory worker can produce a greater number of goods in a more efficient way, than say their counterpart in South Korea, China would gear its policy towards exporting that product rather than wasting resources on a product that can be made more efficiently elsewhere. Many Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) started to take advantage of low labor costs in developing countries and split their production process to ensure efficient production across multiple countries. By doing this, companies increase their profit margin and developing countries begin to industrialize.

According to Dunhaupt, “market mechanisms in vertical GVCs support industrialization and also product and process upgrading under certain conditions.” (Dunhaupt and Herr 2021) Countries such as the Asian tigers have been especially successful in using ISI/ELI strategies to integrate into GVCs. While the literature has suggested that GVC integration leads to better pay-levels and labor conditions, recently these ideas have been called into question. Research has shown that a country must have a strong labor union movement coupled with strong political institutions to enforce labor law. Just because a country is producing what its best at producing does not necessarily mean that the conditions of employment improve.

Countries that have been successful in using GVCs to promote economic growth all used “comprehensive horizontal and vertical industrial policy” (Dunhaupt and Herr 2021). Horizontal integration simply means domestic firms acquiring other firms or merging with each other. Vertical integration occurs when a domestic firm acquires a firm for it to gain an advantage in the production process, hence giving it more say in the full GVC. These two strategies must be used at the same time for GVCs to really have an impact on development. This is usually coupled with massive investment of the government in certain firms or industries to gain more control within the GVC. If a state uses these strategies to fuel economic growth, rapid industrialization usually ensues (Dunhaupt and Herr 2021).

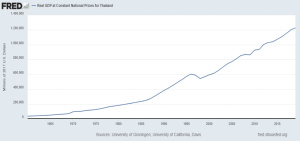

GVC Case Study: Thailand

Thailand at the end of World War II was a primarily agrarian economy heavily dependent on rice with a minuscule manufacturing sector and scant basic infrastructure. (Robinson et al., 1991). Beginning in the 1950s, however, the Thai government adopted a comprehensive industrialization strategy to promote import-substituting industries by attracting private investments in the manufacturing sector and by building up basic infrastructure. Owing to the enormous success of these policies up until the late 1960s, the real GDP per capita of Thailand doubled and the industrial output over this period in agro-industries, textiles, and heavy manufacturing significantly expanded (Robinson et al., 1991). Due to Thailand’s small domestic market and the negative balance of payments that emerged in 1969 and 1970 were driven by the imports of raw materials and capital goods by import-substituting industries, however, the Thai government was forced to shift its policies away from import substitution and towards export promotion.

A few years later, in 1973, the first oil shock resulted in a sharp increase in inflation, a substantial current account deficit, and a marked increase in Thailand’s external debts (Robinson et al., 1991). The Thai government, seeking to restore past levels of economic growth, responded with increased government spending in infrastructure, defense, and energy subsidies, all financed by foreign borrowing. The second oil shock in 1979, however, exposed to Thai policymakers the unsustainable and potentially harmful nature of running a vast fiscal account deficit in the long run. Therefore, the Thai authorities, helped by three arrangements with the IMF and two structural adjustment loans from the World Bank, embarked on a comprehensive adjustment program in 1980 to reduce the fiscal and current account deficits, reverse the protectionist policies of the 1970s, and eliminate the distortion in relative prices by devaluing the Baht (Robinson et al., 1991). While some of the macroeconomic imbalances in the Thai economy persisted, these policies were successful in reducing inflation, raising interest rates, and rendering the Thai economy competitive in the international markets again.

With the advent of 1986, Thailand’s economic woes finally came to an end when Thailand experienced the single, greatest economic boom in its postwar history: a real GDP growth rate of over 10 percent a year between 1986 and 1996 (Warr and Kohpaiboon, 2017). This economic expansion was fueled by an increase in manufacturing exports, which included computer parts, consumer electronics, and travel goods. Additionally, by an increase in foreign direct investment, especially by Japanese multinationals which relocated their plants from Japan to Thailand following the relative appreciation of the Japanese Yen in the Plaza Accords of 1985. As the manufacturing output increased and became more diversified, the construction and services, particularly financial and tourism, sectors also underwent rapid growth (Robinson et al., 1991).

The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, sparked by the Thai government’s elimination of the Baht’s peg to the US Dollar, impelled the Thai government to further reduce restrictions on capital outflows and foreign ownership requirements of domestic automotive production to attract massive foreign investments, which were severely needed to restore the health of the Thai economy (Warr and Kohpaiboon, 2017). Moreover, the establishment of the Eastern Economic Seaboard corridor in the early 1990s included substantial developments in port facilities and related infrastructure, and the further depreciation of the Baht. These policies transformed the Thai automotive industry from a small, domestically focused sector to the ninth largest automotive producer in 2015, nicknamed “the Detroit of the East,” with about 80 percent of the industry’s output exported to other countries (Warr and Kohpaiboon, 2017).

At the turn of the millennium, the Thai automotive industry became further embedded in global value chains. Moreover, in 2014, finished vehicles only made up about half of Thai automotive exports and the rest was made up of intermediate goods in the form of automobile parts and components (Warr and Kohpaiboon, 2017). Today, automobile parts and components made in Thailand can be found in vehicles in Japan, the US, and particularly other Southeast Asian nations. As such, the continued success of the Thai economy, despite significant setbacks, can be traced to conservative economic policies and a growth-oriented outlook, which adeptly adapts to the changing patterns of the world economic order. And, as more and more multinational corporations have shifted towards outsourcing production and conducting different steps of the manufacturing process in different countries, Thailand has been successful in deepening its reach in global value chains by attracting significant investments from foreign multinational corporations.

Effects of Trade: Global Inequality

Evidently, the effects and success of trade policy are not as obvious as economists would suggest. Nonetheless, economists argue that in the aggregate, international trade is beneficial as it results in more output, a variety of goods and services, and increased efficiency, and generally leads to industrialization. There is evidence to suggest however that some of these strategies have disproportionate negative effects on certain industries.

As countries increase production and investment, and depending on the development trade strategy expose themselves to the volatility of international markets they face challenges with the distribution of resources. One of the most widely agreed upon observations from trade theory and policy is that a country’s exposure to international markets influences the allocation of resources within that country and potentially results in “distributional conflict” (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 39). Although research has yet to find a general trend in inequality, current trends in developing countries show an increase. Furthermore, scholars have determined that the increase in exposure due to international trade impacts countries through three mechanisms: changes to labor income, relative prices (consumption), and household production decisions. A common theme that has emerged in literature suggests that globalization influences inequality by altering the demand for skilled workers. The rise in skill premium or the wage gap between high and low skilled workers is the primary contributing factor to rising inequality, particularly wage inequality.

Trade and development have had a variety of effects on countries and communities worldwide as it has contributed to the increase in the mobility of labor, capital, services, and goods across borders. It has fundamentally altered economies and societies by making them progressively interconnected. While it appears that based on the few measures of inequality and globalization that as the global economy has become more interconnected it has also become increasingly unequal, establishing a causal link between globalization and inequality remains challenging as the “mechanisms through which globalization [affects] inequality are country, time, and case specific” (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 78). Existing conclusions on the impacts of trade policy are based on models that are more focused on the costs and benefits to specific sectors rather than how trade policy affects the gap between low and high skilled workers. The relationship between trade policy and inequality, specifically how trade policy may contribute to inequality is an area that needs further research.

Transitional Unemployment

Among the most widely expressed concerns about globalization, the notion that trade liberalization is accompanied by an increase in transitional unemployment as the economy adapts to the volatility of the international markets, is the most common. Unemployment does have important implications for income inequality as it largely affects low-skilled and poor workers. However, yearly total unemployment statistics show that macroeconomic recessions have a larger impact on unemployment than tariff reductions (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 69). Although it is crucial to note that these predictions do not specify which workers or sectors are impacted, hence they can be misleading (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 69). More broadly, there is a limited amount of empirical research that aims to identify the relationship between transitional unemployment, trade, and inequality, largely due to a lack of data sources; a trend that will be observed in the following sections and more generally applies to research about inequality and its causes.

Industry Wages

Industry wage premiums can be defined as the aspects of workers’ wages that are attributable to the workers’ industry affiliation rather than characteristics such as age, experience, and education (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p.70). Trade policies affect industry wage premiums in various ways but due to trade liberalization, wages in sectors composed of mostly unskilled workers decreased relative to the corresponding average wage, contributing to the rise in wage inequality. Nevertheless, there is evidence that the effect of trade liberalization on industry wage premiums was small, thus, it is not clear whether the decrease in these wages is a driving force of wage inequality (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 70).

Economic Uncertainty and Employment

Unlike other areas of research examining the effects of globalization on inequality, there is an existing body of research that has investigated how workers are exposed to greater economic uncertainty via “less secure employment” and “volatile income” due to globalization (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 71). More specifically, trade liberalization exposes both domestic consumers and producers to the unpredictable nature of international markets which results in more price volatility and productivity shocks, subsequently making wages and employment more volatile as well (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 71).

Labor Market Standards

Opponents of globalization insist that it affects inequality because it increases the number of workers employed in the informal labor market which is characterized by low wages and poor working conditions. They argue that trade liberalization increases the level of informality within the labor market because it heightens competition, leading firms to minimize costs by employing more informal workers and ultimately complying less to the labor market standards (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 73) Again, there is little data and research about the relationship between informality and trade reform, and the few studies that have examined it yield mixed results, making these claims controversial. It becomes increasingly clear that the difficulties in acquiring data sources and developing a framework to measure inequality have posed many problems for researchers as demonstrated in the examination of the various impacts of international trade on transitional unemployment, industry wages, economic uncertainty, and labor market standards. Existing research draws many conclusions and can be contradictory, primarily because measuring globalization and inequality is difficult and ambiguous.

Despite these difficulties, research has attempted to document the evolution of inequality by utilizing new and more thorough sources of data from which two trends emerge: developing countries have been more exposed to international markets, especially in recent years and while measuring inequality remains complex, existing measures of inequality in the developing world show an increase in inequality with some countries experiencing severe increases (Goldberg & Pavcnik, 2007, p. 39).

Conclusion

It is quite clear that trade policy and what type of strategy a state decides to employ to grow its economy has a massive effect on development or lack thereof. While some countries such as South Korea, were able to transform their economies using ELI policies and emerge as competitive powers on the international stage, others using ISI policies, such as Brazil were not as successful in the long run. As mentioned much of the research dealing with trade policy and its effect on development can be contradictory. In practice, many countries have moved towards ELI and employ massive state intervention/investment, but they face a more competitive export environment. Research in this area needs to be expanded upon to truly measure the full scope of how trade policy affects domestic industries, namely income inequality and unemployment. Ultimately, this line of research will continue to grow as more and more states are engaging in trade wars and joining the integrated global economy. As more countries develop, inequality will become important to understand and how it can be managed through government trade policy if at all. If there is research to indicate a direct relationship between a certain type of trade policy and rising income inequality, this will become important to the future of trade development. As more countries become competitive in the global trade market, we will see different techniques regarding trade policy and tariffs to stimulate economic growth; and future research would be needed to confirm which strategies would work well and which ones would not work as well.

Works Cited

Cooney, Paul (2022). Paths of Development in the Southern Cone: Deindustrialization and Reprimarization and… Their Social and Environmental Consequences. SPRINGER NATURE.

Cooney, Paul. (2021) “Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) in Argentina and Brazil.” Springer International Publishing AG, Switzerland,

Dünhaupt, & Herr, H. (2021). Global value chains – a ladder for development? International Review of Applied Economics, 35(3-4), 456–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2020.1815665

Goldberg, P.K. and Pavcnik, N., (2007). Distributional effects of globalization in developing countries. Journal of economic Literature, 45(1), pp. 39-82.

Guimaraes, A. Q. “State Capacity and Economic Development: The Advances and Limits of Import Substitution Industrialization in Brazil.” Luso-Brazilian review 47.2 (2010): 49–73. Web.

Haggard, S., Kim, B., & Moon, C. (1991). The Transition to Export-led Growth in South Korea: 1954-1966. The Journal of Asian Studies, 50(4), 850–873. https://doi.org/10.2307/2058544

Karunaratne, N.D. (1980): Export oriented industrialization strategies. Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Verlag Weltarchiv, Hamburg, 15(5), pp. 217-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02924575

Krishnan, R. R. (1985). South Korean Export Oriented Regime: Context and Characteristics. Social Scientist, 13(7/8), 90–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/3520299

Krist, W. Chapter 3: Trade Agreements and Economic Theory. The Wilson Center. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/chapter-3-trade-agreements-and-economic-theory

Manger, M.S. and Shadlen, K.C. (2015). Trade and Development. The oxford handbook of the political economy of international trade, pp. 444-451.

Minns, J. (2001). The Labour Movement in South Korea. Labour History, 81, 175–195. https://doi.org/10.2307/27516810

Robinson, D., Teja, R. S., Byeon, Y., & Tseng, W. S. (1991a). Overview of Economic Developments Since 1950. In Thailand: Adjusting to Success: Current Policy Issues (pp. 4–13). essay, International Monetary Fund.

Stronger open trade policies enable economic growth for all. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2018/04/03/stronger-open-trade-policies-enables-e conomic- growth-for-all

Warr, P., & Kohpaiboon, A. (2017, December 1). Thailand’s Automotive Manufacturing Corridor. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/publications/automotive-manufacturing-corridor-thailand

Images

Historical National Accounts. University of Groningen. (2021, December 13). https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/na/

Real GDP at constant national prices for Thailand. FRED. (2021b, November 8). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RGDPNATHA666NRUG#

Real GDP at Constant National Prices for the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, Province of China. FRED. (2021a, November 8). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RGDPNAKRA666NRUG

Real GDP at constant national prices for the Republic of Korea. FRED. (2021a, November 8). https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RGDPNAKRA666NRUG