1 History of Globalization

The Rise and Fall of Economic Integration

Learning Objectives

Upon competing this chapter and activities, learners should be able to

- Identify the origins of interrelation between international politics and economics.

- Explain the rise and fall of three major historical periods of globalization.

- Relate the historical roots of globalization to hegemonic stability theory.

- Examine the three eras of globalization against the IMF’s four dimensions.

The Rise and Fall of Economic Integration

Globalization has been a hot topic both culturally and politically for a number of years. It is a term that became popularized and more commonly used in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the conclusion of the Cold War. But globalization’s key feature, economic integration, existed in various forms over the past thousand years and has been an issue of tribal leaders, monarchs, and presidents (Vanham, 2019). The existence of globalization should not be taken for granted, as the period between World War I and World War II showed. With economic integration comes potential economic success, which is a big reason that East Asia went from being one of the poorest regions in the world to being a strong competitor against Western economies. They accomplished this through outward-oriented policies that continue to benefit them today (Globalization: Threat or opportunity? 2000).

Public opinion on globalization has fluctuated over the years. For example, in the U.K., some residents felt swept up in the wave of globalization and the ensuing economic pressure prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. Conversely, twin poll results focused on Americans “who voted against the seemingly inexorable tide of growing economic interdependence, cultural diversity and social connectivity that define a globalized world” (Silver et al., 2022). To better explain this fluctuation and difference in public opinion, we will examine the history and explain what led to the rise and fall of the periods of globalization in this chapter. The periods we will discuss in greater detail are referred to as Pax Mongolica, Pax Britannica, and Pax Americana. The Latin word, Pax, translates to peace and relates to categorizing the different eras of globalization in which a powerful empire or country supported a large increase in economic integration. In IPE the association of global peace and prosperity with hegemony, or the existence of an incredibly powerful political entity, is called hegemonic stability theory. Over the past thousand years, we argue the most impressive of these “hegemons” have been the Mongol Empire of the 13th century, the British Empire of the 19th century, and the modern-day United States. We examine each of these in turn.

Studying globalization as a historical phenomenon can show how current events shape international relations today. For example, the international organizations created to promote economic integration across countries such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the United Nations (UN), and the World Trade Organization (WTO) drew on the ideals of trade liberalization from the era of Pax Britannica (What is globalization? 2021). Besides trade, globalization has also impacted the movement of capital across borders through areas such as foreign direct investments, bonds, and stocks. Globalization may also refer to the diffusion of knowledge and ideas, such as the diffusion of Christianity from Great Britain to its colonies, such as India, but our focus in this book is on the economic dimensions of globalization. The IMF states that there are four dimensions of globalization: trade, movement of capital, movement of people, and movement of knowledge and technology (IMF). This chapter will discuss these four categories throughout Pax Mongolica, Pax Britannica, and Pax Americana.

Pax Mongolica (1206-1294)

Early in the 13th century, the world saw a new force appear in the Far East, as a Mongol leader named, Temüjin, began a twenty-year conquest that brought the majority of the world under his rule. In doing this, he had to unite nomadic tribes of the Eurasian Steppe, which spanned from present-day Hungary to northwestern China. His army was incredibly coordinated, fast, and devastating. Additionally, the labor roles within the empire were not always exclusively split between the sexes and often men and women would be found performing the same tasks and duties. Amidst the duration of his conquests, he gave himself the new, more commonly known, name of Genghis Khan. Despite its prosperous beginnings, the Mongol Empire would not last three generations. The reason for the fall of the empire occurred after the death of Genghis Khan, which resulted in a power struggle among his progeny and ultimately led to a division of land and resources that the empire was never able to recover from. Furthermore, his descendants abandoned traditional practices of shamanism and instead turned to Tibetan Buddhism and Islam, and (separately) their armies became less effective. This all proved to be symptomatic of the fateful end of an empire (Cartwright, 2019).

Trade

During its time as a leading world power, the Mongol Empire was forced to address issues that threatened the stability of its economy, and by extension, its relationships with other prominent actors. The Silk Road, through which goods flowed between the empire from East Asia to the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe, was plagued by bandits who would target travelling merchants.[1] Eliminating these bandits became vital to ensure resources got where they needed to go. Mongol hegemony also limited the number of powers involved in trade. Previously, goods moving from China to Eastern Europe had to pass through dozens of territories owned by kings and khans that posed a potential danger to the trade route. Traders could be subject to hefty taxes and unlawful inspections in these territories, but under the Mongols they instead only had to go through inspections and no extra taxes since the Khanate’s conquest merged Asia into a few powers. From this historical example, we can identify two requirements for increased global trade: a decrease in barriers between trading partners and few external security threats. In other words, the easier and safer it is to get to and trade with a foreign merchant, the more trade both parties are willing to do. This was the case when the merchants of Genoa and Venice were willing to frequently trade with the Mongols on the Western edge of the empire once the threat of conquest was gone. Mongol trade appeared with the reinvigoration of the Silk Road, a global hegemon that created a tighter-knit world where “a man could walk from one end of The Mongol Empire to the other with a gold plate on his head without ever fearing being robbed.” (Crash Course, 2012).

Movement of capital

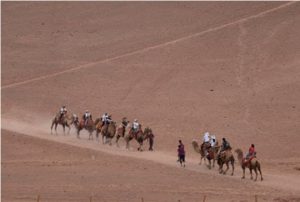

Khan’s method of acquiring capital was through repeated invasions of villages by his substantial army. After consolidating the empire, various streams of trade occurred. However, the Mongols were a nomadic tribe before their conquest, and their lifestyle formed a society that had no merchant class (Enkhbold, 2019). Once the empire emerged alongside the immense capacity for trade, a multitude of merchant classes needed to be created or hired. The ortoq were merchants that had previously engaged in some level of trade with the Mongols and other peoples in inner Asia, using caravans (Figure 1). Once the Khanate was established, the Mongol elite had money to spend and with this came more reasons to spend. Over the century of Mongol globalization, the partnership with the ortoq was a model of trade. Elites trusted merchants with capital to buy specific goods, or sometimes to spend freely, then return with the goods and all accrued interest (Enkhbold, 2019). Though this system and other systems like it, were already in existence before Pax Mongolica, the peace upheld by the Mongol Empire allowed the system to grow.

Movement of people

The actual Mongol people were relatively small in number prior to their conquest of Eurasia; the growth of the empire was due to tactics Genghis Khan implemented in his army, namely the integration of various individuals from an array of ethnic backgrounds into his forces. To continue the conquest, Genghis Khan had those he conquered join the army, not in segregated regiments, but assimilated directly into Mongol units. These foreigners were able to outrank ethnic Mongols with a merit-based system, meaning multiple different types of people were surrounding an officer at a time. The predominantly Mongol army was therefore a principal mover of people throughout the empire.

One of the late names to embrace globalization was the explorer Marco Polo, who went into Mongol China and worked for Kublai Khan as something resembling an ortoq for nearly twenty years. His story is not unusual; many people found themselves moving amongst the empire as Pax Mongolica enabled one of the first instances of widespread human migration in peacetime (Weatherford, 2004).

Movement of knowledge and technology

Pax Mongolica was an early form of globalization; many innovations and inventions were dispersed throughout the empire. The Khans saw the need to regulate and introduced the first taxes upon the empire in the 1230s. Genghis Khan also saw fit to standardize the size of silver throughout the empire to ease trade, something similar to the modern Euro. Later on in the history of the empire, Kublai Khan implemented paper money as a safer and easier way to facilitate banking. Paper money didn’t sink as easily and was easier to protect in transit. Additionally, the empire concocted a new gunpowder formula which yielded a quicker and higher explosive force (Weatherford, 2004). Guns and cannons were also created. An important thing to note, is the fact that Mongol craftsmen were able to engineer these innovations with local materials, omitting the need to travel long distances for resources. With the creation of gunpowder, came hand grenades and other forms of weapons which eventually inspired the modern warfare that we know today.

Summary

The Mongol Empire provided protection from harm, increased trade, and opportunity for wealth on the Silk Road. Over the course of its empire, religious tolerance was implemented, and ideas were traded, as were goods and money. As time went on, the Empire was inching closer to succumbing to its fateful ending. With every Khan’s death, a fight took place to be named the next Great Khan. The real empire was essentially a confederation composed of four Khanates: the Golden Horde, the Il-Khanate, the Yuan Dynasty, and the Chagatai Khanate. Eventually the differences between the Khanates grew too large, and the event that put the Mongol Empire over the edge had bled into its successors. The adaptation and diversity that the Mongols allowed in their empire, the reason it was able to exist, caused distance among the leaders. The trade that brought riches to all of them assisted in the spread of the bubonic plague. As a result, Pax Mongolica was ended after less than one hundred years of control, but the ideas had spread enough for history to know that once there was a world connected by a hegemon. Pax Mongolica was a medieval basis for what globalization could become, and parallels can be seen from Pax Mongolica to Pax Britannica and Pax Americana (Figure 2). Caught in the throes of the Black Death and hostility between Asian powers, the Mongol version of globalization ended.

Pax Britannica (1815-1914)

After defeating its European Rivals, Britain emerged as the financial commercial hegemon from 1815 to 1914, from Napoleon’s defeat by the British military to the beginning of World War I. Britain was motivated by competition with France during the 17th century, leading to the formation of colonies in North America, the West Indies, and later, in India and Africa (Ashworth et al., 2017). At its height, the empire contained 25% of the world’s land (British et al.). Most of these ventures came from companies and industry magnates instead of the English crown. Another key player during this time was the British Royal Army. The presence of the British Royal Army attributed to the spread of “Christianity, commerce, and civilization” to its colonies which in return defended its empire (Gough, 2014). Pax Britannica is thus a “systematic look at how Britain…molded Europe and the World between 1814-1914” (Gough, 2014).

Trade

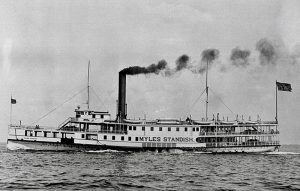

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the British government exercised control over the colonies in trade and shipping under the mercantilist philosophy that reigned dominant during that time (British Empire, 2022). During this period, the principal trade law was the Navigation Act of 1651, which mandated that all colonies exclusively import and export with England. Britain had most of the share of the world trade market. They exported primarily manufactured goods. In turn, they imported raw materials such as tobacco, sugar, tea, and spices from their colonies, bolstered by developments in transportation technology, such as steamships and railroads (Watson, 2014). This era began in 1820 with the movement toward free trade when London merchants opposed the Corn Laws. The aristocracy created these laws in Great Britain to pin tariffs on all grain imports coming into the country (Beard, 2017). After its repeal, American wheat farmers were able to export grain to Great Britain, increasing Britain’s dependence on imports while also forging trade relations with North America (Clark & Raper, 1936).

Another area where the British Empire developed intercontinental trade was with India, specifically the founding of the East India Company in 1600. The Company imported raw goods such as tea, cotton, jute, and rubber from India to the British Empire. As Britain’s manufacturing capabilities improved, it produced manufactured goods made with Indian raw materials sold at a higher price point to Indian consumers (Nasta et al., 2017). Tea was one of the most significant commodities imported into Britain from India, beginning in the 1820s. Over time, it became a “quintessentially English custom…,” and showed that cultural influence flowed both directions (Nasta et al., 2017).

Movement of capital

Britain is considered by many to be the world’s first foreign investor on a large scale. They laid the foundation of modern-day foreign investment. As a world hegemon, Britain had a crucial role in the international financial system, including “direct investment ventures; licensing; and coordination in transnational webs of enterprise” (Shehadi, 2021). Before 1914, British foreign investment stood at £4 billion or 44% of the world’s total foreign investment, with much of it going to British colonies in Africa, Latin America, and Asia (Clark, 2011).

The rise and success of joint-stock companies, such as the Russia Company and the more famous East India Company, meant that companies faced “international risks” (Shehadi, 2021). Multinational enterprises such as these laid the groundwork for modern foreign development practices in the British Empire in colonial holdings, such as “funding the construction of infrastructure (such as railways), or the extraction of natural resources” (Shehadi, 2021). With the laying of submarine cables in the 1860s, Britain was connected to the U.S. (New York), Europe, Asia, Australia (Melbourne), Latin America (Buenos Aires), and Russia. This advancement “changed the informational environment of British investors” (Goetzmann & Ukhov, 2005). By the 1870s, with the development of telegraphs, British investors could “receive news concerning political events worldwide, economic and trade news, and even news regarding the weather and the storms affecting the crops in the colonies” (Goetzmann & Ukhov, 2005). Therefore, it is demonstrated that advancements significantly impacted the flow of capital in the technology sector.

Furthermore, Britain’s economic hegemony manifested as the widespread adoption of the gold and sterling standard. According to Robert Gilpin, an American political scientist, Britain organized the gold standard and, as the hegemon in “…commodity, money, and capital markets, ‘enforced the rules of the system’ upon the world economies” (Clark, 2011). As Britain rose to become the commercial and financial hegemon, it became more common for countries to have a part of their reserves in British Treasury Bills or bank deposits in London, Russia, Japan, Austria-Hungary, Holland, Scandinavia, and British Dominions together “held two-thirds of all foreign exchange reserves” (Eichengreen, 2019). As confidence in London as a financial center increased, countries also began holding large sterling reserves, which became just as, if not more important than, the gold standard in later years (Clark, 2011).

Movement of people

The movement of people during Pax Britannica can be classified into two groups: voluntary and involuntary (slavery). Within the voluntary classification, Britons moved to settler colonies such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, primarily in the 18th century, and facilitated Anglicization by disseminating British values and customs (Free, 2018). Poorer Britons who wanted to move away from Britain’s “crowded and squalid cities” emigrated to Canada, and better-off Britons moved to other parts of the empire for employment opportunities to become governesses, builders, engineers, and farmers (Living in the British Empire: Migration). The Scots, Welsh, and Irish were another large demographic that voluntarily moved around the empire. These travelers moved around the world for the British Empire as military officials, engineers, and doctors (Living in the British Empire: Migration). Finally, in 1845, the Irish fled their country to the U.S., Canada, and Australia because of the Great Famine of 1845-1851, considered the first voluntary mass migration of people (O’Rourke & Williamson, 2001).

However, there was also a large flow of involuntary movement during this time. The British Empire was responsible for the most significant contributions to the slave trade market from 1640 to 1807, transporting 3.1 million Africans to British colonies in the Caribbean, North America, and South America during the transatlantic slave trade (Britain and the Slave Trade). Additionally, convicts were sent to Australia during the 1700s and 1800s. The British also shipped millions of Chinese all over the empire, such as in North America and South Africa, to build railways (Britain and the Slave Trade). Additionally, around 1.6 million Indians were shipped to North America and the Pacific Islands for “farming, mining, and other commercial enterprises” (Britain and the Slave Trade).

Movement of knowledge and technology

As mentioned previously, advancements in technology allowed for the integration and success of the British Empire into the world economy (see Figure 1). From 1760 to 1830, the British Empire underwent the first Industrial Revolution, giving it an edge in the global economy (Inikori, 2021). The development of steamships and railroads allowed goods to be transported over thousands of miles worldwide. The Industrial Revolution resulted in the creation of the factory system and the mechanization of manufacturing. Inventions such as the spinning jenny and power loom increased worker productivity. This was key to Britain’s export of its most important manufactured goods, cotton, to India at 20% of the price in 1700 (Inikori, 2021). In 1851, the English were the first to lay submarine telegraph cables under the English Channel successfully. These cables connected London to the European financial centers (O’Rourke & Williamson, 2001). Thus, these cables made it possible for those in New York, Paris, London, or Berlin to invest in international-scale joint stock companies and participate in more foreign direct investment (Vanham, 2019). Another innovation that was beneficial for investors was the electric telegraph. When a French company constructed the Suez Canal, transport time from Britain to India was further shortened, causing an increase in commercial activity (Vanham, 2019). Combined with the movement of people, religious ideas were created across borders. A prominent example was when British missionaries spread Protestant Christianity to areas in India and Africa. Due to all of these developments, “Britain was the country that benefited most from this globalization, as it had the most capital and technology” (Vanham, 2019).

Summary

The Pax Britannica era ended with the advent of World War I. The outbreak of European tensions signaled to the world that Britain was not strong enough to control up-and-coming powers such as Imperial Germany and the U.S. (Gough, 2014). By the end of the Pax Britannica in 1914, the groundwork for an interrelation globe had been well underway. It was rare to find a town or village whose prices were not influenced by a foreign market, whose infrastructure was not funded by foreign capital, and whose labor markets were not impacted by immigration (O’Rourke & Williamson, 2001). Export industries flourished, and poor regions began chipping away at the wedge that separated them from more affluent areas. Still, not everyone was happy about this. Some capitalists argued that the increased interrelation of financial markets made them vulnerable to economic shocks that originated in foreign countries. Some laborers argued against the import of cheap goods made by cheap labor abroad.

During the Interwar Period (1918-1928), there were several attempts to reinstate British hegemony, but they all failed. Britain experienced 715,000 military deaths, the destruction of 10% of its domestic assets and 24% of its overseas assets (Crafts, 2014). World War I cost Britain over 25% of its GDP, which exhausted the empire (Crafts, 2014). Britain ushered in an era of liberalized trade, but World War I brought it to an “abrupt halt” as countries favored protectionism (Crafts, 2014). Japan and particularly the U.S. could fill in the vacuum left by the British in international markets during the war, such as for cotton textiles. Another attempt was made to reinstate the gold standard at the pre-war parity. However, this was unsuccessful because of the economists’ uncertainty about deflation. After World War I, Britain experienced lower income levels, higher unemployment, lower trade, and an increased public debt-to-GDP ratio (Crafts, 2014). Against this backdrop, the U.S. impacted less than Europe during World War I and emerged as the new hegemon. After World War II, the U.S. cemented its role as a world leader.

Pax Americana

Pax Americana was the new era of globalization that followed World War II and was spurred by the devastation of Europe post-war. Relative to Europe, the U.S. was comparatively unharmed by World War II. Thus, production did not have to recover and the economy was in much better shape than the rest of the world. As such, the U.S. began not only providing for itself, but also for the means of European recovery. Due to the economic success the states were experiencing, public policy under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration benefitted not only war veterans, but most Americans. This post-war glory would be short lived, however, due to the impending Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Trade

Globalization crashed after WWI, and what followed was a period of post-war protectionism and the Great Depression. After WWII, during the 1940s, the U.S. led several efforts to resuscitate the global economy via international trade and investment through international organization, trade treaties, and reductions to trade barriers. Between 1956 and 1957, quotas on dollar trade and other trade barriers were cut dramatically (Horowitz, 2004). It is interesting to note that conversely from the fact that the United States was leading efforts to revive the global economy, the decisions were made unilaterally. The U.S. helped to establish the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, which “became the world’s most important multilateral trade arrangement” (Irwin, 2018). Through negotiating rounds, the GATT was successful at reducing tariff barriers on manufactured goods in industrial countries, helping to promote international trade after WWII. After 1995, the GATT became the World Trade Organization, which manages four international trade agreements: “the GATT, the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), agreements on trade-related intellectual property rights and trade-related investment (TRIPS and TRIMS, respectively)” (Irwin, 2018).

Countries had also signed onto more bilateral or regional trade agreements (RTAs), such as the North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This agreement eliminates tariffs on merchandise and reduces barriers to trade in services and foreign investment between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The U.S. also entered into bilateral trade agreements with Israel, Singapore, Jordan, and Australia, among others. The interconnectedness of the world economy results in increased competition, spurring practices of off-shoring or outsourcing that allowed companies to benefit from the cheapest labor and lowest taxes (Irwin, 2018).

While this era provided cooperation between the United States and other countries, the Cold War alliance structure brought on a new wave of bipolarity between the world’s main powers, the Soviet Union and the United States. The decade of 1945 to 1955 is known as the “era of tight bipolarity” (Agashe, 2021).

Movement of Capital

After World War II, there were significant attempts to globalize finance. One such attempt was the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944, which pegged other nations’ currencies to the U.S. dollar, creating an international monetary system. The vision that those at Bretton Woods had of this system was that it would be one that could provide exchange rate stability, prevent competitive devaluations, and promote economic growth. Eventually, under this new system, large domestic banks became internationalized, especially between 1964 and 1980 (Ghizoni, 2013).

Foreign assistance is another form of moving capital across borders given that it is the largest component of the international affairs budget, and makes up 1% of the entire federal budget. The U.S. has become the largest foreign aid donor in the world, “accounting for nearly 23% of total official development assistance from major donor governments in 2019”, which was the last time data was collected on this topic (Morgenstern & Nick, 2022). The major foreign aid categories include multilateral and bilateral development assistance, humanitarian assistance, strategic economic assistance, and security assistance (Morgenstern & Nick, 2022). One of the most famous examples of the movement of capital during this time was the Marshall Plan, provisioned by the Economic Cooperation Act in 1948. The Plan disbursed more than 15 billion dollars by some estimates to Great Britain, France, and West Germany to spur production and international trade, along with spreading ideals of democracy to contain the spread of communism (Marshall Plan, 2009).

Since 2001, capital has been heavily allocated towards development aid (such as global health programs) and heightened security assistance (such as anti-terrorism measures) directed towards U.S. allies. In 2019, the main countries the U.S. donated to were Afghanistan, Israel, Jordan, Egypt, and Iraq. Thus, reflecting the strategic significance of Israel and Afghanistan, the humanitarian crisis in Jordan, and “long-standing commitments” to Egypt.

Other ways that capital can cross borders is through remittances, or payments made by immigrants in their host countries to their home countries. Remittances can constitute nearly 5% of the home country’s GDP in some cases, indicating how economic globalization is directly linked to the movement of people (Berridge, 2016).

Movement of People

Migration stalled with World War I, but resumed in the 1980s and remained historically high despite the various methods used to control it. Unlike in the eras preceding Pax Americana, the personal and financial costs of immigrating have substantially decreased. Currently, and perhaps due to this fact, the U.S. is the “most popular destination for international immigrants” (Wayne, 2015).

Personal costs decreased as developments in transportation technology made it faster and safer to travel. Financially, new immigrants have been able to benefit from the consequences of economic globalization, typically in the form of remittances, by older immigrants (Berridge, 2016). These substantially lowered costs have allowed for heavy “corridors” of human traffic between less wealthy countries and wealthier countries, such as Mexico and the U.S., or between Turkey and Germany. Migration increased from 446 per million world inhabitants in the 1980s to 603 per million world inhabitants in the 1990s. In the first decade of the 21st century alone, the rate of international migration “exceeded that of the 19th century” (Wayne, 2015). Corresponding to this increase in immigration, there are more formal barriers to migration than permits, passports, and visas than ever. The movement of people has created benefits, yet these benefits are unequal between home and host countries (the latter benefit more — see Figure 2; Wayne, 2015).

Movement of Technology and Knowledge

In 1956, the creation of the shipping container by Malcolm McLean revolutionized trade by reducing shipping and loading costs by nearly 90%, shortening port turnaround times, and lessening merchandise theft. Further developments in container ship technology allow for over 18,000 containers to be shipped overseas for commercial and military purposes (Hoover, 2021). As a result of this creation, 90% of global trade occurs through the sea currently (Ryssdal & Palacios, 2021).

The need for sharing best practices and knowledge across borders, increased as world economies globalized. One such example of this is the Basel I Accords, when banking officials from the three major banking powers, the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan, congregated and tried to harmonize their banking policies. This was attempted by implementing a risk-weighting system for banks. This was done without any formal treaty or state obligation, but by 1994, 92% of the 129 countries had some sort of system in place (Alessi, 2012).

Culture, especially American customs, music, and television has also crossed international borders. America exports culturally salient material such as music, movies, and other forms of media. Furthermore, these exports are seen as new which attracts younger generations. In comparison, older generations may view them with a potential disdain and may worry about the resilience of their own culture. Additionally, deeply-rooted historical traits are painted over to advertise the next superficial fad from America. As a result of this, according to the Pew Research Center, 37 of 46 countries surveyed (excluding the U.S.) cited “Americanization” as having negative effects on their own culture and traditions (Kohut & Wike, 2020).

(Figure 1 here: Evolution of Methods of Trade Globalization)

| Figure 1: Evolution of Methods of Trade Globalization |

| Pax Mongolica

|

| Pax Britannica

|

| Pax Americana

|

Summary

Pax Americana, or Globalization 3.0, was driven by its technological advancements and has brought a lot of benefits and backlash. It has facilitated global economic opportunities, enabling businesses to access larger markets, foster innovation, and lift millions out of poverty. Additionally, it has a widespread cultural exchange, helping societies with diverse perspectives and empowering people to address global challenges. However, globalization has also widened economic inequality, led to environmental degradation, and raised concerns about loss of sovereignty and cultural identity. The backlash against globalization has fueled calls for greater regulation to mitigate its effects and ensure a more equitable and sustainable total global economy. Despite its drawbacks, globalization 3.0 remains a powerful force for economic growth and cultural exchange. Efforts to address its challenges while taking its benefits are crucial for creating a more inclusive and sustainable global society.

Conclusion

Critics from a variety of disciplines such as economy, sociology, and cultural studies recognize that globalization leads to three principles: “increased connectivity, improved technology, and perceived convergence” (Pooch, 2016). These further lead to global interdependence, multidirectional migrations across the world, and the slow decline of national politics. This chapter covered the winners and losers of globalization over the course of its history, as shown in Figure 2.

During Pax Mongolica, those who won were Mongol empire officials and those who traded on and from the Silk Road. However, those who lost during this wave of globalization were people who were forcibly absorbed into the empire. During Pax Britannica, the winners were British empire officials and the British Royal Government as it acquired more colonies and subsequent wealth. To an extent, British citizens benefited from free trade when restrictive trade laws such as the Corn Laws were repealed. However, it may be argued that they too, were losers; benefits reaped from globalization weren’t dispersed evenly, leading to many citizens remaining in poverty. Additionally, Indian, Chinese, and West African citizens who were exploited by the British, yet made up a significant component of globalization, were also harmed because of it. But is globalization popular in the most recent wave of globalization, Pax Americana?

First, it’s important to note that globalization can be visible and invisible. Yet, globalization is more than a cultural melting pot. It occurs on a scale invisible to us such as the mutual connectivity of major world banks, international trade treaties, and foreign aid, among others. The last era of globalization examined is Pax Americana, but how accurate is it to describe this modern age as one of Pax? Foreign policy advisor to former President Obama, Jake Sullivan believes that “the fact that the major powers have not returned to war with one another since 1945 is a remarkable achievement of American statecraft”, or proof of Pax Americana (Is the world getting more peaceful?, 2021). This is further evidenced by the fact that interstate conflict has decreased substantially in the 20th century and after World War II, and the number of interstate conflicts have also decreased from Cold War levels, but not as dramatically (Is the world getting more peaceful?, 2021). Factors that may explain this are characteristics of an era of Pax Americana: the globalization of economics and increased international trade, the globalization of capital, and the spread of democratic norms (Gartzke, 2007). Nevertheless, we are in an era where peace is not “continental” as it was under Pax Mongolica or Pax Britannica. Those eras laid the foundation for a globalized peace (Dizikes, 2017).

| Pax Mongolica | Pax Britannica | Pax Americana | |

| Winners | Mongols, Silk Road Traders, Western Europe | Europe, esp. UK; Colonialists | High skilled manufacturers in wealthy countries, low skilled manufacturers in poor countries |

| Losers | Rulers conquered by Mongols | Colonies, Slaves, Indian and Chinese laborers who worked in poor conditions | Low skilled workers in wealthy countries and high skilled workers in poor countires |

According to the Pew Research Center, most believe that globalization is good for their country, but in practice, many believe “it’s not good for them personally” (Stoker, 2020). This dualism presents a contradiction. Are more people not educated enough on globalization to develop a coherent opinion of it? Or does this nuanced response reflect the opposite, an increasing awareness of globalization and its relative benefits? This skepticism is prevalent among the advanced economies of the U.S., U.K., Japan, and some European nations. According to that survey, 81% of over 48,000 respondents from 44 countries believe that “international trade and global business ties are good for their country” (Stoker, 2020). However, the same survey indicates that only 56% of the respondents believe international trade creates job opportunities and only 26% of the respondents believe that trade lowers prices, despite that being the main arguments for why nations should globalize their economy. American citizens are especially skeptical, with only 17% of Americans believing that trade increases wages, and only 28% agreeing that foreign companies absorbing American companies is good for the country (Stokes, 2020). This suggests that as of late, Americans believe that globalization has turned the tide on them, and for the worse.

Ultimately, it would be fair to say that globalization is popular to everyone except those who directly lose from it, such as low skill manufacturers in highly developed countries and highly skilled manufacturers in less developed countries since their skills and goods are deemed too expensive. Thus, they get left out of the benefits of globalization; after all, what good is an out of season fruit when you can’t afford it? Globalization’s popularity is only as high as the people’s belief that they are winning from it.

The last era of globalization examined is Pax Americana, but how accurate is it to describe this modern age as one of Pax? Foreign policy advisor to former President Obama, Jake Sullivan believes that “the fact that the major powers have not returned to war with one another since 1945 is a remarkable achievement of American statecraft”, or proof of Pax Americana (Is the world getting more peaceful?, 2021). This is further evidenced by the fact that interstate conflict has decreased substantially in the 20th century and after World War II, and the number of interstate conflicts have also decreased from Cold War levels, but not as dramatically (Is the world getting more peaceful?, 2021). Factors that may explain this are characteristics of an era of Pax Americana: the globalization of economics and increased international trade, the globalization of capital, and the spread of democratic norms (Gartzke, 2007). On the other hand, since the end of WWII, the world has still experienced catastrophic conflicts such as

Afghanistan, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, amongst others. John Dower, Ford International Professor of History, Emeritus, and Pulitzer Prize winner, argues that “We’re in a perpetual cycle of violence in the name of preventing violence,” and that the dip in warfare is attributed to “hyperactive militarism”, such as increased involvement in proxy wars and risk of nuclear warfare (Dizikes, 2017). During the Cold War, between 1965 and 1973, the U.S. had deployed 40 times the tonnage of bombs it dropped on Japan onto Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. The War on Terror following the Sept. 1, 2001 terrorist attacks have led to protracted and costly conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other areas in the Middle East (Dizikes, 2017). In terms of recent events, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 is a symptom of the fact that the U.S. does not wield the same coercive power as it did during President John F. Kennedy’s administration. Still, many believe that the U.S. should play a leading role in addressing the conflict because of its unique economic, military, and geographic position in the world. Nevertheless, we are in an era where peace is not “continental” as it were under Pax Mongolica or Pax Britannica. Those eras laid the foundation for a globalized peace (Dizikes, 2017).

Questions for Reflection

- How did globalization differ across each era on each of the IMF’s four dimensions and why? (learning objectives 1,3,4)

- What factors contributed to the rise and fall of each era? (learning objective 2)

- Compare the strengths and weaknesses of the three eras on the IMF’s four dimensions. (learning objective 4)

- Discuss the progression of Pax Americana and its impact on the United States’ role in shaping international relations in the modern age. (learning objective 1)

Works Cited

Agahse, A. (2021, April). International Journal of Research Culture Society ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume 5, Issue 4, Apr 2021, from https://ijrcs.org/wp-content/uploads/IJRCS202104006.pdf.

Alessi, C. (2012, July 11). “The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/basel-committee-banking-supervision Accessed 18 Apr. 2024.

Ashworth, W., O’Brien, P., Inikori, J., Austin, G., & Lukasiewicz , (2017, November 2). British Imperialism and Globalization, 1650-1960. British Imperialism and Globalization, 1650-1960. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from http://wehc2018.org/british-imperialism-and-globalization-1650-1960/.

Beard, S. (2017, August 28). How the British Began a Free Trade

Bonanza. Trade Off: Stories of Globalization and Backlash. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.marketplace.org/2017/08/28/how-the-british-began-free-trad e-bonanza/.

Berridge, S. (2016, January). International Migration Patterns Amid Globalization : Monthly labor review. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2016/beyond-bls/international-migration-p atterns-amid-globalization.htm.

British Empire Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/empire/intro/overview2.htm.

Cartwright, Mark. “Mongol Empire.” World History Encyclopedia, https://www.worldhistory.org#organization, 7 Aug. 2023, www.worldhistory.org/Mongol_Empire/

Clark, G., & Raper, R. (1936). The Oxford History of England. Clarendon.

Clark, I. (2011). Hegemony in international society. Oxford University Press.

Crafts, N. (2014, August 27). Walking Wounded: The British Economy in the Aftermath of World War I. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://voxeu.org/article/walking-wounded-british-economy-aftermath-wo rld-war-i.

Crash Course. (2012, May 12). Wait For It…The Mongols!: Crash Course World History #17 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szxPar0BcMo.

Dizikes, P. (2017, June 27). Is the Pax Americana truly peaceful? Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://news.mit.edu/2017/john-dower-book-pax-americana-truly-peacef ul-0627.

Eichengreen, B. J. (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2022, March 13). British Empire. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/place/British-Empire.

Enkhbold, E. (2019). “The Role of the Ortoq in the Mongol Empire in Forming Business Partnerships.” Central Asian Survey. 38(4). 531–547.

Free, M. (2018). Settler colonialism. Victorian Literature and Culture, 46(3-4), 876–882. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1060150318001080.

Gartzke, E. (2007). The Capitalist Peace. American Journal of Political Science, 51(1), 166–191.

Ghizoni, Sandra Kollen (2013). “Creation of the Bretton Woods System.” Federal Reserve History, www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/bretton-woods-created

Goetzmann, W., & Ukhov, A. (2005, April). British Investment Overseas 1870-1913: A Modern Portfolio Theory Approach. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.nber.org/papers/w11266.

Gough, B. (2014). Pax Britannica Ruling the Waves and Keeping the Peace before Armageddon. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Hoover, G. (2021, January 21). Malcolm McLean: Unsung Innovator who changed the world. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://americanbusinesshistory.org/malcolm-mclean-unsung-innovatorwho-changed-the-world/.

Horowitz, S. (2004). Restarting Globalization after World War II. Comparative Political Studies, 37(2), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003260980.

Inikori, J. E. (2021). The Industrial Revolution and Globalization: A discussion of Patrick O’Brien’s contribution. Journal of Global History, 17(1), 165–171. https://doi.org/10.1017/s174002282100036x.

International Monetary Fund. (2000, April 12). Globalization: Threat or opportunity? An IMF Issues Brief. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/041200to.htm#II.

Irwin, D. (2018, August 29). International Trade Agreements. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/InternationalTradeAgreements.html.

Is the world getting more peaceful? (2021, April 7). Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://oneearthfuture.org/news/2021-04-07-world-getting-more-peacefu l.

Kohut, A., & Wike, R. (2020, July 28). Assessing Globalization: Benefits and Drawbacks of Trade and Integration. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2008/06/24/assessing-globalization/.

Marshall Plan. (2009, December 16). Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/marshall-plan-1.

Morgenstern, E., & Brown, N., R40213Foreign Assistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy (2022). Frisco, TX; Congressional Research Serive.

Nasta, S., Stadtler, F., & Visram, R. (2017). Global trade and Empire. South Asians in Britain. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.bl.uk/asians-in-britain/articles/global-trade-and-empire.

The National Archives. (n.d.). Britain and the Slave Trade. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/slavery/pdf/britain-and-the-trade.pdf.

The National Archives. (n.d.). Living in the British Empire: Migration. Case Study 6 Background. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/empire/g2/cs6/backgroun d.htm.

New World. “Mongol Empire.” New World Encyclopedia, 18 Oct. 2018, Silver, L., Schumacher, S., Mordecai, M., Greenwood, S., & Keegan, M. (2022, April 7).

O’Rourke, K. H., & Williamson, J. G. (2001). Globalization and history: The evolution of a nineteenth-century Atlantic economy. MIT Press.

Peterson Institute For International Economics. (2021, August 26). What is globalization? What is Globalization? Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.piie.com/microsites/globalization/what-is-globalization.

Pooch, M. U. (2016). Globalization and Its Effects (Ser. Toronto,

New York, and Los Angeles in a Globalizing Age, pp. 15–26). Transcript Verlag. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1wxt87.5.

Ryssdal, K., & Palacios, D. (2021, November 23). How the Shipping Container Revolutionized Freight and Trade. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.marketplace.org/2021/11/23/how-the-shipping-container-rev olutionized-freight-and-trade/.

Shehadi, S. (2021, October 12). How the British Empire Created Foreign Investment. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/analysis/british-empire-created-foreign -investment.

Silver, L., Schumacher, S., Mordecai, M., Greenwood, S., & Keegan, M. (2022, April 7). In U.S. and UK, globalization leaves some feeling ‘left behind’ or ‘swept up’. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/10/05/in-u-s-and-uk-globalizat ion-leaves-some -feeling-left-behind-or-swept-up/.

Stokes, B. (2020, July 28). Most of the world supports globalization in theory, but many question it in practice. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/09/16/most-of-the-world-su pports-globalization-in-theory-but-many-question-it-in-practice/.

Vanham, P. (2019, January 17). A brief history of globalization. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/how-globalization-4-0-fits-into -the-history-ofglobalization/.

Watson, A. (2014, April 8). A quick exploration of ten nineteenth century British imports. A Quick Exploration of Ten Nineteenth Century British Imports. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://tradingconsequences.blogs.edina.ac.uk/2014/04/08/a-quick-expl oration-of-ten-nineteenth-century-british-imports/.

Wayne, M. (2015). International Migration Remains the Last Frontier of Globalization. Federal Reserve of Dallas. Retrieved from https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/research/eclett/2015/el1502.pdf.

Weatherford, J. (2004) Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press.

- For a nice interactive map of the Silk Road, see https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/silkroad-interactive-map. ↵

![Alex ‘Florstein’ Fedorov [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0) or FAL], via Wikimedia Commons Container ship](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/3124/2022/09/pax-americana_1-1-300x199.jpg)