14 Finance: The Great Recession of 2007-08

The Great Recession (2006-2009), often referred to as “the subprime mortgage crisis” and “the 2008 financial crisis” is historically the second-worst economic recession to have plagued the American economy. The aftermath of the recession was extensive, Bems et al. (2013) note “From 2008 to 2009, real-world trade fell by about 15 percent, exceeding the fall in real GDP by roughly a factor of 4”. The consequences of the Great Recession were wide-ranging, but the dismantling of the housing market would have the most significant effect for years to come. Homeownership had been a central component of the American dream; as real estate and property value steadily increased, many Americans began to rush toward the thriving market, until it popped. This chapter will analyze how the combination of various factors would result in the great financial crisis and how the impacts of the resulting policies have shaped our world today. By the end of this chapter students should be able to identify the four causal theories behind the Great Recession, be knowledgeable about the origins and development of the Great Recession, understand the political impacts of the Great Recession, and be able to differentiate between the policy responses of the U.S. and Europe and understand the effects each had.

Background

Mortgaged Backed Securities

A mortgage involves a bank lending a buyer money to buy an asset such as a home. This mortgage can be bought and sold by other parties while the buyer slowly pays back the loan plus interest to whoever holds the mortgage. Lenders began to bundle thousands of these mortgages and then to sell them to investors as mortgage backed securities (MBS) (Duca 2013). MBS were originally fairly low risk, high reward, as the interest accrued from these securities was high, and strict and responsible lending practices decreased the chance of people defaulting on their mortgages. Even if there were some who defaulted, the investor would still receive compensation in the form of the assets of the defaulters, which they could sell off to recover their losses. Ratings agencies acknowledged the safety of these investments by labeling them as AAA bonds.

Seeing the safety and profitability of MBS, investors both domestically and abroad became increasingly interested in buying up MBS shares. Unfortunately, the subsequent rise in demand could not be met by the number of mortgages made available by responsible lending practices. In response, lenders loosened the restrictions on qualifying factors for loans, granting loans to people with insufficient qualifications, poor credit, and low income. The housing bubble continued to grow as the increased demand for housing, loans, and MBS was met by banks’ irresponsible and predatory lending practices. Predatory lending practices can be conceptualized as the fraudulent and deceptive tactics lenders utilized to dupe borrowers into mortgage loans beyond their means. Despite the risk associated with these new loans, referred to as subprime mortgages, they were not rated as risky. Instead, they were packaged alongside AAA rated bonds and sold as low risk to investors. This allowed investors to receive high returns on the ‘junk’ mortgages. The industry that was at one time considerably stable had become much more fragile.

Collateralized Debt Obligations

Another important financial instrument at play was the Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO). CDOs pay investors from its grouping of financial revenue-delivering resources. In this case, the CDOS were made up of mortgages. As mortgages were paid, investors received returns through betting that mortgages would continue to be paid. These CDOs were separated into tranches based on risk, like the MBS arrangement.

Timeline

2000: 2000 is a significant starting point as there is little evidence of any subprime lending prior to the turn of the century. After 2000, however, there was a dramatic increase of subprime lending rising in correlation to the price of housing (Bailey 2008). This correlation is attributed to previously unqualified individuals becoming qualified for loans, resulting in an increase in demand for homes. This led to housing becoming increasingly expensive and bigger loans being given to more people with previously insufficient qualifications.

January-March 2006: The first quarter of 2006 was when the housing market began to turn. The bubble popped when people began to default on loans. Once mortgage payments began to balloon, because of irresponsible and predatory lending, the occurrence of defaults soared. The economy witnessed a very rapid decline in the housing market, although supply was up, demand was considerably low.

October-December 2006: As large financial institutions became aware of the conditions of the housing market, they halted any more purchases of subprime mortgages, and the banking lenders of these mortgages were left with a substantial amount of loans. As a result, Ownit Mortgage Solutions, a subprime lender, would end up having to declare bankruptcy in December of 2006(Bailey, 2008).

April 2007: The bankruptcy of New Century Financial on April 03, 2007 is often seen as a key landmark of the financial crisis. New Century Financial had once dominated the United States as its largest mortgage lender, so its bankruptcy forecasted an emergency in the housing market amid a spike in homeowner defaults.

June 2007: On June 12, 2007, it was announced that two Bearn Stearns-managed hedge funds, both of which had invested in subprime asset backed securities, were on the brink of bankruptcy due to the decline in value of highly rated MBSs. The following week Bearn Stearns attempted to bailout out its hedge funds but by July both had filed for bankruptcy (Bailey 2008). Although financial institutions and banks were able to recoup their losses in the form of assets, the demand for housing was so low at this point that they would’ve had to sell at a loss. Similarly, those who were still paying towards their mortgage found that they were paying for homes that had plummeted in value. This led to even more people defaulting on their mortgages because it wasn’t worth it to keep up the payments on such low valued homes.

July 2007: As an increasing number of borrowers defaulted, the CDOs also failed to deliver returns, causing investors to lose billions of dollars. In the span of seven years, 2000 to early 2007, Bear Stearns had quadrupled its stock price. But in just a few months their stock had plummeted, losing 90% of its value in July of 2007 (Bebchuk). Bearn Stearns also began looking for alternate avenues as they approached bankruptcy.

August 2007: Countrywide Financial was a major provider of home loans in the early 2000s, owing much of its revenue to the profitability of subprime loans. In late August, Bank of America bought Countrywide in response to their $20 billion depreciation in value and the emergence of ethical investigations regarding their lending practices (Fraedrich 2014).

January 2008: In the first part of January, The World Bank predicts that global economic growth will slow in 2008, as the credit crunch hits the richest nations. In the latter half, Global stock markets, including London’s FTSE 100 index, suffered their biggest falls since 11 September 2001.

March 2008: In March of 2008, there was a run-on Bear Stearns leading the government to assist JP Morgan in their acquisition of Bear Stearns by promising $30 billion of subprime-backed securities (Bailey, 2008).

September 2008: The biggest shocks came in September. On September 15, 2008, financial giant Lehman Brothers filed a bankruptcy petition in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York (Ball, 2018). The next day the U.S. government announced that they would bail out American International Group (AIG) due to their status as a “too big to fail” company. AIG had been a crucial player in the market and is credited for the insurance policy known as credit default swaps (CDS). CDS were insurance contracts sold against mortgage-backed securities. Imitating the function of home insurance, they provided protection against the risk of defaults. When the capabilities of AIG’s CDS insurance policy proved deficient, the credit rating of AIG depreciated, and they were required to pay the money promised. The result was a near-failure of the institution with a loss of $99.3 billion in 2008. (McDonald and Paulson 2015, 81). On September 25-26, 2008, the bankruptcy of Washington Mutual became the biggest bank failure in U.S. history having “. . . $307 billion assets, $188 billion deposits, and over 2,300 branches in fifteen states when it failed” (FDIC).

Late 2008 – 2009: Over the next few months, the financial crisis worsened. Merrill Lynch, a large financial institution, was sold to Bank of America with the support of the U.S. Government. The Federal government also reassumed control of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-sponsored enterprises, both centered in the U.S housing finance system (Frame, 2015). The effects of the Great Recession did not stay within the bounds of the United States. Soon concern centered on the growing sovereign debt of several European Union members, resulting in the start of the 2009 Eurozone crisis (Lane, 2012).

Causal Theories

Throughout the Great Recession, there was consistent debate as to its causes. Over the years, explanations have generally fallen into four categories: (1) bad monetary policy, (2) financial innovations, (3) moral hazards generated by the government, and (4) global economic imbalances. Although the debate over this topic continues, it is widely accepted that the convergence of these four aspects is what triggered the Great Recession.

Bad Monetary Policy

The bad monetary policy referred to here is the decision of the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates low in an effort to pull the economy from a state of recession. The 2001 recession was the result of the lack of foresight on the developing asset price bubbles, Bailey et al., expounds “There had been an overinvestment in technology capital stock in the 1990s, and the subsequent slump in technology investment after the tech bubble burst was instrumental in the causing of the 2001 recession”.

It should be noted that failure to reduce interest rates would likely have made climbing out of the 2001 recession much more difficult. The biggest failure of monetary policy during this time is not necessarily the failure to raise interest rates but that the government failed to pay attention to the red flags associated with the growth of the housing bubble and react accordingly. Following the Dot-Com bubble, they should have been more aware of the dangers associated with bubbles and realized that there was a need to raise interest rates again when the price and demand for housing began to increase so rapidly.

Financial Innovations

When it was realized how much profit could be made from the use MBS and CDO, banks were eager to come up with ways to generate progressively large returns on investments. Without the oversight and risk assessment of ratings agencies and the SEC, the profitability capable of being made by using these instruments incentivized increasingly risky and irresponsible business practices. Economist Xavier Vives (2010) provides insight, “Prior to the 2007 crisis, banking had evolved from the traditional business of accepting deposits and granting and supervising loans, to providing services to investors (asset/investment fund management, advice and insurance) and companies (consultancy services, insurance, mergers and acquisitions, underwriting share offerings and debt securities, securitization, risk management), while also engaging in proprietary trading”. This shift in the roles of banking institutions facilitated the implementation and misuse of MBS and CDO which in turn led to an increase in deceptive and predatory lending practices in order to meet the demands of investors.

It is also believed that risky ventures were promoted within financial firms, such as Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns, by compensation structures that produced large cash bonuses to the highest earners. Although it is not believed that either institution made risks knowing the market would collapse, Bebchuk argues that these compensation structures incentivized executives to make decisions that they knew would likely result in massive losses sometime down the road (Bebchuk 2010). In this way, MBS, CDO, and the compensation structures within financial institutions played a large role in facilitating behavior that would ultimately lead to the market crashing.

Moral Hazards

The third explanation offered is that U.S. government policies created a moral hazard in the market. The argument made is that the leaders of the largest financial institutions acted under the assumption that they were safe from systematic risks, knowing that regulators were not acting to rein them in, and that the government would bail them out if a crisis occurred because of their behavior.

“Too big to fail” refers to the government’s tendency to bailout and otherwise assist large banks, financial institutions, and companies when they are in trouble. The companies and institutions that fall into this category are deemed to be so important to the economy that government will inject millions of dollars into them, to keep them afloat. It can be argued that these practices have greatly aided in cushioning the blows of bursting economic bubbles. It could also be said that an institution’s “too big to fail” status, is a reason why they are a safe investment (Shull 2012). But others feel that large institutions and companies willingly take on more risk knowing that if the market does take a turn for the worse, they can rely on the government to bail them out. During and following the 2008 financial crisis, many pointed to this as the reason why so many big firms failed to adequately assess the riskiness of their investments.

Arguably the largest role the government played in the cause of the 2008 financial crisis was the failure of the SEC to scrutinize the practices of the ratings agencies. While these agencies are private firms, they are overseen by the Securities and Exchange Commission who is responsible for ensuring transparency and legitimacy in firm dealings. The fact that the SEC was clearly not living up to its duties in this sense created a moral hazard. As a result, it is argued that these firms abdicated their responsibility to rate the mortgages and financial instruments accurately and instead delivered the ratings that allowed banks to get higher returns on their investments.

Global Economic Imbalances

Lastly, while the Great Recession originated in the U.S, it is necessary to analyze how global imbalances ignited the crisis. The Asian Financial Crisis (1997), commonly referred to as the “global saving glut”, is often noted to have had major implications on economies across the globe, including on the U.S. economy. The fall of U.S interest rates has direct ties to the situation that emerged from the Asian Financial Crisis, understood as the decision of emerging markets to send capital to developed countries. Once the U.S began to receive capital it subsequently resulted in the decline of returns received from long-term investment, specifically Treasury bonds (Yu, 2015).

None of these explanations stand alone. Each one of them represents an important part of the financial crisis and in combination, they resulted in an economic failure that would not only affect every corner of the United States but would also permeate the borders of countries abroad.

Policy Response to the Crisis

Governments have two economic levers at their disposal: fiscal policy and monetary policy. Both mechanisms of action were key in responding to the 2008 economic crisis. Even though the crisis began in the United States and originated due to US financial machinations, the entire global financial apparatus was intertwined through a network of mortgage-backed securities and highly leveraged debt. The interconnection of the financial system meant that every country was affected; governments across the globe were forced to react. Key policy differences emerged in the wake of the crisis. The contrast between Europe and the United States is especially instructive here to help understand two contrasting positions on the role of government in response to the economic crisis. Emerging from the crisis, the big policy debate was between intervention and austerity. The United States generally took a more interventionist response at both the monetary and fiscal levels through quantitative easing, lowering interest rates, and fiscal stimulus. However, Europe took a more conservative approach and injected capital in a more targeted manner, focusing on stimulus to specific adversely affected industries, debt guarantees, and asset purchases.

The United States’ response to the crisis spanned three presidential administrations and was the focus of 5-8 years of national debate. The response can generally be viewed in two phases: Bush-era and Obama-era responses, the repercussions of both would be felt throughout the oncoming decade. Between these two eras it is also important to focus on how the 2008 financial crisis directly affected the 2008 presidential election, specifically John McCain’s bid for presidency.

While the Presidency of George W. Bush was not characterized by fiscal restraint, the administration was reluctant to intervene excessively in the economy through fiscal stimulus due to fears of government bloating (Hennessy & Lazear, 2013). However, the Bush response was characterized by two significant stimulus bills. First was the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. Enacted on February 13, 2008, this bill focused on providing tax rebates to single Americans making less than $75,000 a year and families making up to $150,000 a year to the tune of $600 per individual taxpayer and $300 per child (Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, 2008). The bill also contained provisions for disabled and senior citizens and significant tax breaks offered for housing-related investments. The administration expected that this expansionary measure would boost household spending and wave off recession.

When the Economic Stimulus Payments (ESPs) arrived, households did raise their spending “…by ten percent in the week the payment arrived and by 4 percent over the 7 weeks including and following arrival,” (Broda & Parker, 2014). This had a small, but noticeable effect on consumer demand “…we estimate that the receipt of the ESPs directly raised the demand for consumption by between 0.5 and 1.0 percent in the second quarter of 2008 and by 0.16 to 1.81 percent in the third quarter of 2008,” (Broda & Parker, 2014).

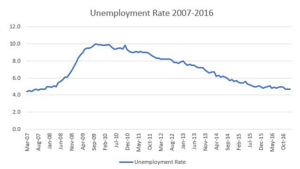

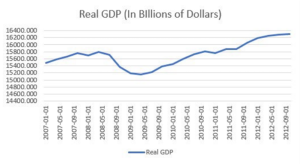

Yet, the view of most mainstream economists is that this was too little, too late; the crisis persisted. Real GDP growth shrunk from 2.2% in Q4 2007 to 1.4% in Q1 and Q2 of 2008 (Figure 2). With GDP forecasted to plummet further and the unemployment rate skyrocketing to 6% and climbing, (Figure 1) the administration decided to pass another bill authorizing the Treasury Department to attempt to stabilize the market through a variety of different interventions.

This bill, The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, provided the Treasury with the leeway to purchase up to $700 billion in troubled assets to remove these assets from companies balance sheets. However, only $475 billion of these funds were authorized (Zestos, 2016). The thought process behind the bill was that since financial firms carried significant debt in the form of worthless bonds made up of subprime mortgages, the government could purchase these toxic assets and allow the firms to proceed with decreased liability. While 934 institutions received funds through TARP, much of the funding was concentrated in the hands of a few firms (Zestos, 2016). Nearly 70% of total TARP dispersions were distributed to only twelve firms since these firms were dubbed ‘too big to fail’ and cumulatively carried trillions of dollars in assets. The top two, AIG and General Motors, are clearly not the typical financial institutions bailed out during crisis.

The political conversation around TARP became especially fraught, with critics focusing on companies using federal funds to increase executive pay as an example of how forcing the government to take on the risk that these companies incurred simply encouraged negligence. However, the program is widely credited with helping stave off an intensification of the economic crisis.

The 2008 financial crisis also had major effects on that year’s presidential race. During the 2008 presidential race, Senator John McCain failed to gain public confidence due to his apparent lack of economic experience, which gave voters little confidence he would be able to handle the financial crisis taking place. Initially, he indicated that the US economy was doing well; however, the banking sector in the United States was reeling from one of the most severe shocks in decades. In a later statement, Senator McCain explained that he was referring to the productive and resilient character of work in the United States, but that did little to restore confidence in his competence. McCain continues to attempt to deflect criticism of his lack of economic experience by saying that his words about the underlying soundness of the economy were addressed to American workers.

McCain had a hard time connecting with the American people while adhering to the president’s economic policies and delivering a message of optimism and compassion to them. Before revising his position and recommending that the government assist families in keeping their homes, John McCain stated that the United States of America is in a better place now than it was eight years ago.

The comment McCain made about the robustness of the fundamentals had been made on other occasions for more than a year, and had been causing some concern among voters, failing to restore confidence among voters that he could handle the 2008 crisis. The fact that he made the same comment in September 2008, when the fall of Lehman Brothers led to the stock market downturn, became detrimental to his campaign and would be cited as one of the reasons for his electoral loss later that year.

In January 2009, President Barack Obama took office, leading a country that was weathering an 8%+ unemployment rate and had seen 3 consecutive quarters of declining GDP (Figures 2 & 3). The President’s first major piece of legislation was the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. This bill sponsored a planned $787 billion (total outlays would amount to $840 billion) in fiscal stimulus. This stimulus was more focused on providing relief to low and middle-income taxpayers and in providing boosts to economic activity through increased funding on mandatory spending (Medicare/Medicaid, unemployment insurance, etc). Taking place over the course of 10 years, the goal of this bill was to sustain economic growth. This package included nearly every sector of the economy, aiming for a holistic revitalization effort for consumers and businesses.

The Obama administration also introduced several regulatory reforms under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2011. These reforms focused on providing consumers protection against financial sector risks by minimizing the scope of risky activities that financial institutions could undertake. For example, the Volcker Rule was designed to ban proprietary trading by commercial banks to minimize the number of speculative investments that put consumers’ funds at risk.

Monetary Policy

The role of U.S. monetary policy in managing the Great Recession can be analyzed through three efforts. First, the Fed lowered the target federal funds rate from 5.25% in August 2007 to 0% by December 2008 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), 2022). This was intended to spur economic activity by decreasing barriers to borrowing money that would be used for starting businesses, building homes, or personal spending. Secondly, the Fed operated as a ‘lender of last resort’, offering a variety of different programs to help inject liquidity into troubled markets. These liquidity programs peaked at $1.6 trillion in value by December 2008 (Wessel, 2011). These programs allowed credit markets to stabilize, increasing financial trust and confidence. By 2008, the Fed turned to Quantitative Easing, the purchasing of financial assets held by banks in exchange for currency reserves. This had the effect of increasing the domestic money supply, feeding the market with capital, leading to increased investment and economic activity.

European Response

Europe represents a distinct counter-factual to the United States’ approach. While the United States immediately responded with different stimulus packages and expansionary monetary policies, the EU, after one large stimulus package, eventually turned to austerity, cutting spending and raising taxes, in order to deal with the long-run effects of the crisis. The so-called ‘Troika’, the European Central Bank, the European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund, guided the response for the Eurozone countries. These three institutions heavily pushed budget cuts and shrinking the welfare state in response to what they saw as a fiscally unsustainable European budget.

These responses are often compared to each other because the US recovery and the European recovery resulted in different outcomes. The United States recovery was slow but consistent. Europe recovered in 2009, around the same time as the United States, but then fell into another recession in 2011 that lasted for two years. By 2014, unemployment in Europe was twice that as the U.S. (12.1% compared to 6.7%) and in Spain and Greece, two nations who cut their government spending the heaviest, their unemployment was at 26.7 and 27.8% in 2014. (Weisbrot, 2014) These results are typically linked back to the austerity response. “After some stimulus in both areas, the eurozone governments also engaged in more and earlier budget tightening than the United States did; and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has shown a clear relationship between this fiscal tightening and reduced GDP growth.” (Weisbrot, 2014).

As we can see in Figure 4, the Keynesian approach fared better in restoring GDP to pre-crisis levels in comparison to the austerity approach adopted by the European countries. These effects are clear in the data. “Some countries, such as Germany, are also experiencing sustained growth, but those that adopted stringent austerity policies, such as Ireland, Greece, Spain, and Portugal, have yet to recover. Iceland, one of the worst affected countries, held a referendum on austerity; 93% of the population rejected it and, so far, austerity has been delayed and limited. As a result, Iceland has had much better economic performance than the latter group of austerity cases…” (McKee et al., 2012)

The comparison is not perfect because the EU economic system is different from the United States, however, one can analyze the effects of the United States’ and EU’s measures. In a paper analyzing the austerity response, economists from the University of Michigan and Switzerland found that “…austerity in government purchases – defined as a reduction in government purchases that is larger than that implied by reduced-form forecasting regressions is statistically associated with below-forecast GDP in the cross-section.” (House et al., 2017)

However, the United States’ approach is also imperfect, with many researchers citing the slow recovery rate experienced by the economy as a reason why the approach was lacking. Nonetheless, it is seen that the European approach failed to instigate long-term recovery, while the United States approach mostly succeeded. This had significant repercussions for how policymakers responded to future crises.

Long-Term Effects

By the end of 2008, twelve out of thirteen of America’s most important financial institutions were on the edge of failure. According to the IMF, eighteen of the twenty largest financial institutions accounted for over half of the losses reported during the recession. Countries with rapid credit growth and larger current account deficits while leading up to the crisis felt the policies made during the crisis were constraining or too restrictive. However, stricter rules on bank activity limited the possibility of such a crisis occurring again. Countries with stronger fiscal positions experienced smaller losses during and after the crisis. The significant fiscal stimulus packages offered by most countries helped mitigate the current crisis from spreading and prevent other crises from occurring.

Globalization offers many benefits, but the globalization of finance creates an environment of interdependence that can cause crises in one country to spread throughout the globe. The 1982 Debt Crisis was driven by dollar-denominated bank loans to developing countries, the Asian Financial Crisis was driven by financial outflows and international speculation against fixed exchange rates, and the US housing market crash was driven by excessive lending made possible by financial inflows from other countries. In each case, international finance caused domestic issues to spread beyond their borders. Weinberg (2013) states that among the economies that experienced a banking crisis in 2007–08, about 85 percent are still operating at output levels below pre-crisis trends. The long-term effects of the crisis can be seen in countries’ economies and in their responses to crises.

Economic legacy

The OECD performed research looking into how economies recovered from the Great Recession, comparing pre-crisis trends and projects with the actual outcomes in output and jobs that occurred after the recession. They found that “Among the 19 OECD countries which experienced a banking crisis over the period 2007-11, the median loss in potential output in 2014 is estimated to be about 5½ per cent, compared with a loss in aggregate potential output across all OECD countries of about 3½ per cent.” (Ollivaud & Turner, 2014).

This loss in output is not the only detrimental consequence of the crisis. Its legacy is also seen in the rate of long-term unemployment. Economists found that “Both short-term and long-term unemployment increased sharply in 2008-9 during the Great Recession. But while short-term unemployment returned to normal levels by 2013, long-term unemployment remains at historically high levels in the aftermath of the Great Recession.” (Kroft et al., 2014).

The lasting effects on output and unemployment translated into real effects on citizens in these countries. In the years following the recession, the trail of damage that was left in its wake has been clearly identified. “We estimate the impact of the Great Recession of 2007–2009 on health outcomes in the United States. We show that a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate resulted in a 7.8–8.8 percent increase in reports of poor health. Mental health was also adversely impacted, and reports of chronic drinking increased.” (Wang et al., 2017).

Policy Legacy

One can see lessons learned from the Great Recession in counties’ responses to the economic decline caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Policymakers responded rapidly, passing large fiscal stimulus, and eventually spending trillions in order to avert another crisis. Moody’s analytics studied the effect of this significant fiscal stimulus on the recovery from COVID-19 and found “The massive global fiscal policy response to the pandemic deserves significant credit for limiting the severity and length of the recession that occurred when the pandemic struck, and for the subsequently strong global economic recovery” (Yaros et al., 2022) Wary of repeating their mistakes in the Great Recession, most governments responded with significant stimulus, causing a V-shaped recovery, allowing their economies to bounce back with strength.

This recovery was not perfect. As the U.S.’s strong fiscal response caused a rise in inflation and interest rates, there was a depreciation in the value of securities that banks had invested in. This led to the recent collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, the second largest banking failure in U.S. history. In response, the government bailed Silicon Valley out and has promised to stand behind the deposits of all banks to decrease the likelihood of runs (Turner, 2023). While the U.S. has surely learned some lessons on economic damage control, the same cannot be said for the part they play in creating moral hazards in banking systems and financial markets.

Conclusion

The Great Recession showed the effects of a globalized and financialized economy. It is also illustrative of some of the greatest debates in the worlds of fiscal and monetary policy: intervention vs. austerity in the fiscal arena and contractionary vs. expansionary monetary policy. As the world grows more and more interconnected, the lessons from the Great Recession will only become more salient.

References

Baily, M. N., Johnson, M. S., & Litan, R. E. (2008,). The origins of the financial crisis .Brookings. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-origins-of-thefinancial-crisis/

Ball, L. M. (2018). The Fed and Lehman Brothers: Setting the Record Straight on a Financial Disaster. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/9781108355742

Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, Alma Cohen, and Holger Spamann. “The Wages of Failure: Executive Compensation at Bear Stearns and Lehman 2000-2008.” Yale Journal on Regulation 27, no. 2 (December 31, 2010): 3. http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/1/12025608/1/SSRN-id1513522.pdf.

Bems, R., & Johnson C. J., & Yi, K. (2013). The Great Trade Collapse (NBER Working Paper No.18632). National Bureau of Economic Research.Annual Review of Economics. https://www.nber.org/papers/w18632

Ben Bernanke, (2010), Monetary policy and the housing bubble: a speech at the Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, Atlanta, Georgia, January 3, 2010, No 499, Speech, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.)

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US). (2022, April 20). Federal Funds Target Range. Retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DFEDTARL

Broda, C., & Parker, J. A. (2014). The Economic Stimulus Payments of 2008 and the Aggregate Demand for Consumption. Journal of Monetary Economics, S20-S36.

Cooper, Michael.(2008), McCain on U.S. Economy: From ‘Strong’ to ‘Total Crisis’ in 36 Hours. The New York Times. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/17/world/americas/17iht-mccain.4.16251777.html.

Duca V. J., (2013). Subprime Mortgage Crisis. Federal Reserve History, 23. Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. (2008). H.R. 5140. 117th Cong. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/5140

FDIC. “Status of Washington Mutual Bank Receivership.” FDIC: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.fdic.gov/resources/resolutions/bank-failures/failed-bank-list/wamu-settlement.html.

Fraedrich, John, Ferrell, Jennifer Sawayda, and Jennifer Jackson. “Countrywide Financial: The Subprime Meltdown.” Center for Ethical Organizational Cultures- Auburn University, 2014. https://harbert.auburn.edu/binaries/documents/center-for-ethical-organizational-cultures/cases/countrywide.pdf.

Frame, Fuster, A., Tracy, J., & Vickery, J. (2015). The Rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(2), 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.2.25

Guillen, Mauro F. “The Global Economic & Financial Crisis: A Timeline.” The Lauder Institute. University of Pennsylvania – The Lauder Institute. Accessed April 23, 2023. https://lauder.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Chronology_Economic_Financial_Crisis.pdf.

Hennessy, K., & Lazear, E. (2013, September 16). Who really fixed the financial crisis? Retrieved from Politico: https://www.politico.com/story/2013/09/who-really-fixed-the-financial-crisis096794

Houde, J.-F., Newberry, P., & Seim, K. (2017). Economies of density in e-commerce: A study of amazon’s fulfillment center network. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23361

House, C., Proebsting, C., & Tesar, L. (2017). Austerity in the aftermath of the Great Recession. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23147

Kroft, K., Lange, F., Notowidigdo, M., & Katz, L. (2014). Long-term unemployment and the Great Recession: The role of composition, duration dependence, and non-participation. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20273

Lane. (2012). The European Sovereign Debt Crisis. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26(3), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.3.49

McDonald, Robert, and Anna L. Paulson. “AIG in Hindsight.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 29, no. 2 (April 17, 2015): 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.2.81.

McKee, M., Stuckler, D., Belcher, P., & Karanikolos, M. (2012). Austerity: A failed experiment on the people of Europe. Clinical Medicine, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.12-6-603a

Shull, Bernard. “Too Big to Fail: Motives Countermeasures, and the Dodd-Frank Response.” Levy Economics Institute, February 2012. Accessed April 13, 2023. https://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/too-big-to-fail.

Turner, John. “Why Did Silicon Valley Bank Fail?” Economics Observatory, March 17, 2023. Accessed April 20, 2023. https://www.economicsobservatory.com/why-did-silicon-valley-bank-fail#:~:text=The%20collapse%20of%20Silicon%20Valley,hold%2Dto%2Dmaturity%20securities.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2022, April 20). Real Gross Domestic Product [GDPC1]. Retrieved from Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPC1

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2022, April 20). Unemployment Rate. Retrieved from St. Louis Federal Reserve: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE

Wang, C., Wang, H., & Halliday, T. (2017, May). Health and health inequality during the Great Recession: Evidence from the PSID. Economics and human biology. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29413585/

Weisbrot, M. (2014, January 16). Why has Europe’s economy done worse than the US? The Guardian. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/jan/16/why-the-european-economy-is-worse

Wessel, D. (2011, December 7). Separating Fact from FIction on the Fed’s Loans. Retrieved from Wall Street Journal: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204083204577082331689233426 World Bank. (2021, October 1). Africa Overview. World Bank. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview#1 World Bank. (2022, April 12). Overview.

World Bank. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview#1

Written by Mico Mrkaic, Senior Economist. “The Most Surprising Long-Term Impacts of the 2008 Financial Crisis.” World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/10/lastingeffects-the-global-economic-recovery-10-year s-after-the-crisis.

Weinberg, John. “The Great Recession and Its Aftermath.” Federal Reserve History, https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-recession-and-its-aftermath#:~:text=From%2 0peak%20to%20trough%2C%20US,5%20percent%20to%2010%20percent.

Vives, X. (2010). The Financial Industry and the Crisis. In Smits, R. (2002). Innovation studies in the 21st century;: Questions from a user’s perspective. Technological forecasting and social change. (321-329). BBVA.

Yaros, B., Rogers, J., Cioffi, R., & Zandi, M. (2022, February 24). Global Fiscal Policy in the Pandemic. moodysanalytics.com. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/article/2022/global-fiscal-policy-in-the-pandemic.pdf

Yu, Q., Fan, H., & Wu, X. (2015). Global Saving Glut, Monetary Policy, and Housing Bubble: Further Evidence.

Zestos, G. K. (2016). The Global Financial Crisis: From US Subprime Mortgages to European Sovereign Debt. New York: Routledge.