10 Finance: After Bretton Woods

Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, students should be able to:

- Identify economists’ predictions on how the post-Bretton Wood economy would change worldwide.

- Describe how the role of the G5 and G7 affected the International Political Economy.

- Examine the dilemmas of small and big countries as their competitors went off the Bretton Wood system.

- Relate the changes after the Bretton Wood era to today’s world.

The collapse of the Bretton Woods System marked the beginning of the Post-Bretton Woods monetary system. The period encompasses the end of the Bretton Woods System to today. Following the Nixon Shock in 1971, the international community entered the Post Bretton Woods System. By 1971, the U.S. economy was experiencing stagflation – this is when an economy is suffering from both inflation and recession, where unemployment is high, and there is little economic growth – and President Nixon sought to devalue the dollar in gold (Amadeo 2022). The devaluation plan did not work and eventually caused the price of gold to increase sharply within the free market, marking the end of the Bretton Woods monetary system. The main factors of the eventual collapse of the system can be attributed to institutional changes and, of course, the ability to convert gold to the dollar. Many events contributed to the issues that led to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system.

The Post Bretton Woods Monetary System is significant because it ushered in a new era of economic policies used by countries today. Following the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, most countries allowed their currencies to float, but this policy changed relatively quickly. Some smaller countries in the Caribbean fixed their exchange rate to the U.S. dollar, while countries such as Japan and the United States continued to float their currencies (Annual Report on Exchange 2019). The post-Bretton Woods Era marked an era in which countries worldwide had varying international monetary policies. It also marks an era in which no currency anchors the international monetary system in place, as was the case during the Gold Standard and the Bretton Wood System.

Arising from the Post Bretton Woods System were global crises like the Asian Debt Crisis of 1997 and the Great Recession, which demonstrate the problems with the fall of the Bretton Woods System, including economic imbalances and a lack of a clear orthodox foreign policy. The issues arising from the post-Bretton Woods System led to the creation of groups such as the G5, a group of powerful countries including the U.S., Germany, and Japan established in the mid-1970s to coordinate their economic policies (A Guide to Committees 2019). The G5 was formed due to the lack of an international monetary policy plan vacuum that followed the fall of the Bretton Woods System. The creation of the G5 is an example of the many attempts made by countries to create an economic plan that is unified across countries, whether it includes a few or all countries.

The Post Bretton Woods System is relevant in studying the international economy as it is both the successor of the Bretton Woods System and the current system the global economy is in. Studying the Post Bretton Woods System can provide an overview of the various impacts of the Bretton Woods System and an outlook into what the future of the international economy will look like without a unified economic system in place. This chapter will discuss the historical background that led to the Post Bretton Woods System, the current system (or a lack of a system), case studies on countries using fixed and floating exchange rates, and more.

Historical Background

The origins of the post-Bretton Woods system can be traced back to the era when the

Bretton Woods system was still around, during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The Bretton Woods system had its pros and cons in the eyes of its critics, though some wanted to end Bretton Woods more than others, especially in America, as the system was causing issues for the U.S. Dollar. The most notable figure in American politics who wanted to end the Bretton Woods system was Richard Nixon, the eventual 37th President of the United States.

Nixon believed the Bretton Woods system was holding the dollar hostage, so he sought to end it. In the book Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the Twentieth Century by Jeffrey A. Frieden, he notes that “Nixon regarded his close loss to John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election as the result of the Fed’s willingness to raise unemployment to defend the dollar” (Frieden 2006, 314). Kennedy, who was Nixon’s opponent, opposed taking the dollar off the gold standard, as he believed there was no possible use in the United States devaluing its currency.

But despite President Kennedy’s wishes, the U.S. government was already finding it difficult to maintain the value of the U.S. dollar (Frieden 2006, 344). Trouble first emerged in 1959 and 1960, when the American payments deficit led to less confidence in the dollar (Frieden 2006, 344). The Federal Reserve had raised interest rates to increase demand for the dollar in foreign markets, driving the American economy into a recession. As the 1960s continued, Frieden notes that “the problem was made more pressing by the two wars the country was fighting: the Vietnam War and the large increase in spending known as the War on Poverty” (Frieden 2006, 344). Due to the unpopularity of the Vietnam War and the War on Poverty, both the Johnson and Nixon administrations resorted to deficit spending. As a result, inflation sharply rose (Frieden 2006, 344).

What happened next was a “real appreciation” of the dollar, as its exchange rate was held constant while American prices rose, meaning that foreigners had less buying power with their dollars (Frieden 2006, 344). Frieden states that the Bretton Woods rules at the time “required people around the world to accept dollars as if they were worth one thirty-fifth of an ounce of gold, or four Deutsche marks, or five franks, but in fact, they were worth less than this, by some calculations 10 or 15 percent less” (Frieden 2006, 344). The strong dollar spelled good news for Americans, as they could buy more foreign goods and make foreign investments for less; they could travel to foreign countries for less, and in 1971.

However, the strong dollar spelled doom for the Bretton Woods system, as it drove foreigners away from using it as they had lower purchasing power than Americans. In response, the United States resorted to imposing capital controls and taxing American foreign investments to try and stem the outflow of dollars. Still, foreigners wanted to dump the dollar, and it became too expensive to defend the gold-dollar price, as there was not enough gold in either the world or American reserves to buy up all the world’s dollars (Frieden 2006, 345). Another factor that increased pressure on America to devalue the dollar and move away from the Bretton Woods system was the country’s trade position – prices in America became more expensive than in other countries, resulting in foreigners buying less from America. In contrast, Americans bought more from foreign countries (Frieden 2006, 340). In 1971, the United States experienced its first-ever trade deficit, as the strong dollar led to American products becoming more expensive, increasing competitive pressure on American manufacturers (Frieden 2006, 340).

To try and stop the bleeding, the Nixon administration was presented with two possible solutions. The first one, according to Frieden, “was to impose austerity on the U.S. economy to restore the purchasing power of the dollar” (Frieden 2006, 345). He notes that doing this would have lowered American prices and returned the dollar to its official value (Frieden 2006, 345). The other solution was that “the American authorities could raise American interest rates high enough to attract foreigners back to dollars; if the Federal Reserve raised interest rates two or three percentage points, investors might buy more American bonds, increasing the demand for dollars and shoring up their price” (Frieden 2006, 345). Nixon was dissatisfied with both potential solutions and ultimately decided to take the dollar off gold on August 15, 1971, causing the value of the dollar to drop 10 percent, which was then reinforced by imposing a 10 percent import tax, as well as wage and price controls (Frieden 2006, 341-42). The dollar was once again devalued by 10 percent in 1973, and as a result, the U.S. experienced a trade surplus, the economy began to recover, and the unemployment rate declined (Frieden 2006, 342). This marked the beginning of what we know today as the post-Bretton Woods monetary system.

The Bretton Woods system enforced a fixed exchange rate. Since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, International Monetary Fund members have been free to choose any form of exchange they want and allow their currency to float freely, to peg to another currency, or to adopt the currency of another country. After the Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1973, most countries allowed their currencies to float, but that quickly changed. Small countries with large trade sectors disliked floating their currency. Many smaller Asian economies and countries in Central America and the Caribbean fixed their exchange rate to the dollar. Countries like the Netherlands and Austria traded with Western Germany and fixed their exchange rates to the German mark (Friedman, Meltzer. n.d).

A country with a fixed exchange rate can sacrifice its independent monetary policy. A small country open to external trade has little scope for independent monetary policy. Still, a large country cannot maintain an independent monetary policy if its exchange rate is fixed and its capital market remains open to inflows and outflows. Given the reduced reliance on capital controls, many countries abandoned fixed exchange rates in the 1980s to try to preserve some power over domestic monetary policy (Friedman, Meltzer. n.d).

Large economies such as the United States, Japan, and Great Britain continued to float their currencies, as well as Switzerland and Canada; some small economies have preferred to retain some influence over domestic monetary conditions. One of the countries that made the opposite choice is Hong Kong which chose to fix its exchange rate to the U.S. dollar even though it used to be a British colony and is now part of China. Some countries stepped further from independent policy by adopting the U.S. dollar as their domestic currency. The most notable change of this general type was the decision by most of the continental European countries to surrender their local currencies in exchange for a new common currency, the Euro (Friedman, Meltzer. n.d).

In the late 1970s, and as part of the Keynesian theory, some countries were in favor of a free market economy, such as the United States, Canada, Germany, and Switzerland, and moved from a social-liberalism political philosophy to a neoliberalism one by abolishing their capital controls; they were following the example set by the United Kingdom in 1979 and most other advanced and emerging economies followed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Some countries believed capital control was bad and not beneficial, but things changed, especially in 1997 with the Asian Financial Crisis. Asian nations that kept their capital controls, such as India and China, could credit allowing them to escape the crisis unscathed. Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad imposed capital controls as an emergency measure in September 1998, effectively reducing the damage of the crisis.

When the Bretton Woods System collapsed, many economists predicted a bleak future for the world economy, especially for the future of fixed exchange rates. Economists believed that the chances of returning to a fixed exchange rate would likely not be the case or the solution for countries (Thunder in the Air 1973). Some economists believed that returning a fixed exchange rate would cause countries’ monetary policies to collapse and leave behind more adjustment problems (Thunder in the Air 1973). Interestingly, this has not been the case for many countries pursuing a fixed exchange rate. Depending on the goals and policies of a country, a fixed exchange rate can allow it to thrive in a world where capital mobility is increasing. To understand where economists were coming from when making their decisions, it is essential to understand the Mundell-Fleming Model and fixed vs. floating exchange rates.

Mundell-Fleming Model Applied to the Post-Bretton Woods System

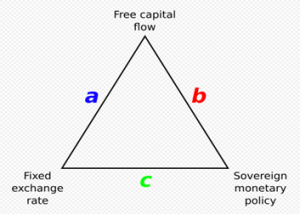

The Mundell-Fleming Model presents a “dilemma” for countries in which they must choose an economic policy that contains two of the following three components: free capital mobility, fixed exchange rate, and monetary autonomy. The model aimed to determine how to analyze the differences between an economy with flexible and fixed exchange rates (Mundell 2001). The concept behind the model demonstrates that a country must choose two of the three options in its international monetary and fiscal policy. A country cannot incorporate all three options into its international monetary policy.

For example, “A country that wants to fix the value of its currency and has an interest-rate policy free from outside influence… cannot allow capital to flow freely across its borders” (Two out of Three 2016). The dilemma presented explains the Mundell-Fleming Model trilemma in which countries must choose two of the options available to them. Today, most countries favor the free flow of capital and autonomous monetary policy. Most economists assume that capital has become so mobile that countries face the choice between autonomy in their monetary policy and stability through fixed exchange rates (Majaski 2020).

Following the fall of the Bretton Woods System, countries had to choose between tying the value of their currency to another currency (fixed exchange rate) or determining their country’s currency by the foreign exchange market (floating exchange rate). Smaller countries like the Bahamas are likely to fix their currency rate to a superpower like the United States and the European Union (Annual Report on Exchange 2019). Doing so protects them from paying more when importing products from developed countries. It also helps smaller countries attract foreign investment and stabilize inflation (Fixed Exchange Rate 2022). However, a fixed exchange rate’s downside is that it limits the central bank’s ability to adjust interest rates to boost the economy.

A floating exchange rate is when the foreign exchange market determines a country’s currency price. Currencies that have floating exchange rates can be traded without any restrictions. It also allows governments to intervene to keep the currency at a fair value (Fixed Exchange Rate 2022). Typically larger countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom are more likely to have a floating exchange rate. The downside of the floating exchange rate is that the currency is more likely to be volatile because its value is based on the foreign market.

Case Studies

Once the critical terminology is precise, we can focus on analyzing case studies. We will focus on four cases to further understand the Post-Bretton Woods era. The first two case studies show how countries can unite to address international economic issues: G5 and G7. The second two will focus on the dilemmas of small and big countries as their competitors went off the Bretton Wood system. We will focus on Hong Kong and the Euro to explore why countries choose fixed or floating exchange rates.

The Group of 5 and the Plaza Accord

Many international groups have been formed to deal with International Political Economy issues. The Group of 5 (G5) is an example of these groups. The group comprised France, Germany, Japan, the U.K., and the United States. The alliance between these significant industrial countries was established in the mid-1970s, shortly after the fall of the Bretton Woods system (A Guide to Committees 2019). The alliance’s purpose was to coordinate the economic policies of the countries in the group since there needed to be more international cooperation once the Bretton Woods system failed. The Plaza Accord of 1985 was the most relevant Accord between these countries. The purpose of the Accord was to weaken the U.S. dollar to reduce the increasing U.S. trade deficit. They did this by manipulating exchange rates through the depreciation of the U.S. dollar in comparison to the Japanese yen and the German Deutsche mark. The imbalances caused by the failure of the Bretton Wood system that they attempted to correct were explicitly between the U.S. and Germany and the U.S. and Japan. However, their policy changes were only half successful since they failed to fix Japan and U.S. imbalances. Unfortunately, this failure was linked to Japan’s “Lost Decade” of low growth and deflation (Friedman et al. 2023).

The Accord stated that the U.S. would reduce the federal deficit while Japan and Germany would boost domestic demand through policies such as tax cuts. Leading up to this agreement, the U.S. dollar appreciated over 47.9%. The appreciation pressured the U.S. manufacturing industry because it made imported goods relatively cheaper. The pressure led influential companies to lobby Congress to step in, which resulted in the Plaza Accord. The yen and Deutsch mark increased significantly through the policies implemented by Germany and Japan, allowing the dollar to depreciate. The goals of the Accord were, therefore, accomplished. However, it did not entirely eliminate the trade deficit between the U.S. and Japan (Friedman et al. 2023).

The Plaza Accord allowed Japan to solidify itself as a powerful player in the international market; however, only some results were positive for the country. The Plaza Accord pushed Japan to increase trade and investment with East Asia, which allowed the country to gain some independence from the United States economy. The rising yen led to a substantial short-term shock to Japanese export-based industries. The government conducted a massive expansionary monetary and fiscal policy campaign to counter this shock and boost the domestic economy. These new policies created enormous credit and asset price bubbles in Japan’s markets. Finally, once the bubbles burst, a period known as the “Lost Decade” happened in Japan. This decade was distinguished by low growth and deflation. This was an unintentional effect that the Plaza Accord had on one of its member countries (Friedman et al., 2023). Once the G5 accomplished its goals, two more countries joined, creating the G7.

The G7 Group is an intergovernmental group comprising the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, and France. All these countries have shared political, social, and economic values, such as representative governments, liberal democracies, and free markets; in fact, the G7 countries made up more than half of the global net worth in 2020 (Zachary, McBride. 2014). Russia was part of this group until 2014, and when Russia decided to annex Crimea in March of 2014, the other group members suspended Russia’s membership in the “G8.”Many scholars argue that Russia was an essential member of the group, even though Russia does not share the same political and economic values as the rest of the member countries. In fact, the G7 group became more influential once Russia joined (Zachary, McBride. 2014).

Case: Hong Kong and the United States Dollar

A case study we will explore in this chapter is Hong Kong pegging itself to the U.S. dollar as a fixed currency. Hong Kong’s economy is externally oriented, meaning it is led by exports (Chiu 2001). Hong Kong was an affected country as its competitors went off the Bretton Woods system. Hong Kong is prone to challenges in its financial system due to “the structure of the economy, characterized by a high degree of openness, complete absence of exchange controls and sizable financial flows” (Chiu 2001). Hong Kong has a long history of having a fixed exchange rate because it needs a currency to anchor itself to bring economic stability. After the Bretton Woods era ended, the Hong Kong dollar floated for nine years between 1974 and 1983. In the beginning, it was a prosperous era for Hong Kong, with a growth of over 10%, and inflation wavered from 4-6% from 1974 to 1976. By 1979, it all began to slow down, and prosperity was ending due to the growth of a broad money supply and domestic loans escalating to average annual rates of 35% and 43% (Chiu 2001).

Consumer inflation surged to over 15% from 1980 to 1981, and the exchange rate of the Hong Kong dollar depreciated by over 20% from 1979 to 1982 (Chiu 2001). These economic problems were caused by Hong Kong’s lack of an effective monetary anchor to peg its currency. There was a lack of governmental control over the supply of interbank liquidity or interest rates; the government had no control or oversight over it. In the early 1980s, Hong Kong attempted to mend the problem by introducing piecemeal measures in the early 1980s to slow down the excessive credit and monetary creation (Chiu 2001). This would allow the Exchange Fund to borrow from the interbank, leading to a stricter liquidity requirement for interbank deposits (Chiu 2001). It was not the most effective strategy, so the government turned to persuasion to influence retail deposit rates set by the Hong Kong Association of Banks (Chiu 2001). At the same time, there was uncertainty regarding Hong Kong’s political transition, and nervousness about how adequate the banks were functioning led to uncertainty in its currency. The Hong Kong Dollar fell 15% in two days, and it caused the public to go into panic (Chiu 2001). Hong Kong linked itself to the U.S. dollar at a fixed rate of HK $7.80 to restore economic confidence (Chiu 2001). Reforms were added to oversee banks to avoid another crisis focused on interbank liquidity and stricter guidelines. The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis also affected Hong Kong by having a high unemployment rate and bringing volatility to its economy. Hong Kong quickly recuperated by buying stock and implementing more reforms in 1998. With an unpredictable move, the government bought HK$118 billion (US$15 billion) worth of stock purchases to lower the interest rate (Chiu 2001). The reforms the government implemented were to provide transparency in the currency board arrangements and have even more explicit expectations for liquidity rules (Chiu 2001).

“Having experienced five consecutive quarters of negative year-on-year growth, the Hong Kong economy started to recover in the second quarter of 1999 and staged a distinct rebound in 2000, with real GDP growth of around 10%.” (Chiu 2001). The Post Bretton Woods Era showed how resilient Hong Kong’s economy is and how successful it has been since pegging itself to the U.S. dollar.

Case: The Euro

A case study we will explore in this chapter is the Euro and how it is a floating currency whose value changes based on supply and demand. In January 1999, eleven of the fifteen countries in the European Union merged their national currencies into a single European currency and made the Euro. The motivation behind the currency merger was to bring economic stability to the European Union. The creation of the Euro would bring currency stability because there would be no exchange rate risk since the Euro would be used in the European Union. The Euro would also lower transaction rates because it would only handle one currency rather than each country in the European Union having its own.

Moreover, it would reduce inflation because of the independent European Central Bank.

Lower inflation would stabilize countries with poor inflation records, such as Spain and Italy.

During the creation of the Euro, members agreed to limit budget deficits under a Stability and Growth Pact. The Stability and Growth Pact is a set of rules designed to ensure that countries in the European Union pursue sound public finances and coordinate their fiscal policies (Europa Commission). It began with the Maastricht Treaty signed in 1992 by European member states, which paved the way for the creation of the Euro as the common currency of the European Union (Europa Commission). The Maastricht Treaty evolved into the Stability and Growth Pact, where European Union member states agreed to strengthen the monitoring and coordination of national fiscal and economic policies to enforce the deficit and debt limits (Europa Commission). Throughout the years, there have been amendments made.

Although preventative measures have been put in place for the Euro to succeed, the economic crisis in Greece due to the 2010 revelation that they had been misstating their public spending demonstrated some flaws in the system. Overall the Euro has brought economic stability and prosperity to the European economy by having an international presence. States with dominance in the global economy meet in international groupings such as the IMF and the G8 to promote stability in the global market. The Euro is the second most important world currency (European Union 2022). It also increases financial integration, making investment capital easier and more efficient since only one currency exists (European Union 2022). The cost of transferring100€ has been reduced from 24€ to 2.40€ since rules on cross-border euro payments were introduced in 2001. Member states also benefit from resistance to external shocks due to the size and strength of the European Union. The member states are more resilient if there is any volatility or turbulence in the global economy (Europa Union). As of 2019, the Eurozone has 19 member states and is used in non-European states such as Monaco, Vatican City, Kosovo, San Marino, and Montenegro. Inflation is low in the member states, wavering at under 3%. The Euro has fluctuated over the years, reaching a low of $0.82 in 2000 and a high of $1.58 in 2008.

The Current International Monetary System

After the Bretton Woods system ended, the international finance world entered a “non-system” era. However, the Bretton Woods system created essential institutions we currently have as remnants of the Bretton Woods system, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank (Kugler, Straumann. 2020, 666 – 667).

The International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was established in 1944. It was the first attempt to create an international institution that could maintain fixed exchange rates based on the international cooperation of the central banks among the participant countries. The

IMF was established on twenty articles agreed upon to create the Bretton Woods system. The IMF’s duty is to provide liquidity to member countries struggling with financial deficits. Even though the Bretton Woods system collapsed in 1971, the IMF remains in function, and it has developed over time, especially with the consecutive financial crisis (Kugler, Straumann. 2020, 668 – 676). Before the 2008 financial crisis, there was a need to change the IMF’s

policy to prevent future crises. First, the boom in the markets, the enormous inflows of capital, and emerging economies reduce the despondency of IMF lending. Second, the critical opinions from within and outside of the IMF. One of the major criticisms was that the institutional rhetoric had not been matched by policy action to address poverty or income distribution. Instead, the IMF kept its policy to maintain macroeconomic stability. Third is financial programming. The central banks worldwide lost their core policies and shifted to an inflation-targeting system. Then the IMF, the World Bank, and the U.S. Department of Treasury agreed to reform the IMF’s policy. Many critics’ analyses questioned the function of the IMF. Marxist analysis sees the IMF as an institution to maintain the hegemony of the United States and Wall Street (Reinhart, Trebesch. 2016, 3-6).

After the 2008 global financial crisis, the world hoped for a new Bretton Woods system to save the global economy after the financial crisis became too severe. The French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, and the British Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, hoped for a “new Bretton Woods” during the G20 meeting in November 2008 (Helleiner 2010, 619 – 620). The financial crisis was the worst the world had ever seen since the Great Depression, and then the Bretton Woods System came along in 1944 as a constitution for the financial system. However, the post-Bretton Woods era is known as the globalization and deregulation of the financial market. The non-system model in the 1980s and 1990s encouraged countries to adopt more financial liberalization policies and to deregulate current policies; neo-liberal values limited the states’ abilities and supported free financial markets. Importantly, it should be noted that Margaret Thatcher, a former prime minister of the United Kingdom, and Ronald Reagan, a former president of the United States, were advocates for neo-liberal values. They both came to office when the global financial system needed a new model to adopt, and one of Thatcher’s first decisions was to end Britain’s 40-year-old exchange control system (Gabor

2010). An international debt crisis in the early 1980s pushed the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to try to protect global markets from countries that defaulted or might default. Nonetheless, the 2008 financial crisis was one of the consequences of the non-system model and deregulation; it made the countries rethink their policies and implement more regulations on the global financial system (Gabor 2010).

Conclusion

Overall, the Bretton Woods system had many advantages and disadvantages. Bretton Woods provided a stable exchange rate that allowed international trade growth. On the other hand, it was a complex structure to maintain long term since it required the coordination of policies among member countries, and people lacked confidence in the system.

After the system failed, many economists theorized that, after Bretton Woods, fixed exchange rates would vanish (Thunder in the Air 1973). However, countries have shown that using fixed exchange rates can allow economies to thrive. Using Mundell-Fleming and understanding fixed and floating exchange rates are essential to analyze the impact of Bretton Woods and the post-Bretton Woods era.

Some examples analyzed in this chapter to further understand this era are the G5 and G7 and case studies of Hong Kong and the Euro. The G5 and G7 prove that countries will work together to rebuild the international economy after Bretton Woods (A Guide to Committees 2019). The Hong Kong case study is fascinating because the government decided to link its currency to the U.S., even if the Bretton Woods System failed because countries were linked to the U.S. dollar. When done correctly, Hong Kong proves that fixed exchange rates benefit certain economies (Chiu 2001). On the other hand, the Euro is an excellent example of how floating exchange rates are also beneficial depending on the situation. The Euro’s value changes based on supply and demand. This approach of currency allows twenty European countries to thrive under the umbrella of the European Union (Europa Commission).

Furthermore, the post-Bretton Wood era allowed the creation of new international economic structures still present today. Some examples of these structures are the IMF and the World Bank. The Bretton Woods system created a new wave of globalization still alive today. Understanding the creation, the destruction, and the repercussions of the Bretton Wood system allows us to understand patterns in International Political Economy. After this chapter, we will explore multiple examples of events that have been impacted by the Post Bretton Woods System in place.

The Bretton Woods system will never be replicated again due to the complexities of attempting to manage the entire world. Furthermore, this attempt will set the tone for new crises, such as the Asian financial crisis and the 08 crisis, that will be covered in future chapters.

Bibliography

“A Guide to Committees, Groups, and Clubs.” 2019. IMF. 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/A-Guide-to-Committees-Groups-and-Clubs.

Amadeo, Kimberly. “How a 1944 Agreement Created a New International Monetary System.” The Balance. The Balance, May 26, 2022. https://www.thebalance.com/bretton-woods-system-and- 1944-agreement-3306133.

“Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions 2018.” International

Monetary Fund. International Monetary Fund, April 16, 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Annual-Report-on-Exchange-Arrangements-and-

Exchange-Restrictions/Issues/2019/04/24/Annual-Report-on-Exchange-Arrangements -and-Exchange-Restrictions-2018-46162.

“Benefits of the Euro.” European Union. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/euro/benefits_en.

Chiu, Priscilla. “Hong Kong’s Experience in Operating the Currency Board System.” International Monetary Fund, 2001. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/seminar/2001/err/eng/chiu.pdf.

“Fixed Exchange Rate.” Corporate Finance Institute. Corporate Finance Institute, December 16, 2022. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/fixed-exchange-rate/.

Frieden, J. A. (2006). Chapter 15: The End of Bretton Woods. In Global Capitalism: Its Fall and Rise in the Twentieth Century (pp. 341–346). essay, W.W. Norton & Company.

Friedman, Milton, and Allan Meltzer. “After Bretton Woods.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. Accessed April 29, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/money/After-Bretton-Woods.

Gabor, Daniela. 2010. “The International Monetary Fund and its New Economics.” Wiley Online Library, (September). https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01664.x.

Helleiner, Eric. 2010. “A Bretton Woods Moment? The 2007-2008 Crisis and the Future of Global Finance.” In International affairs (London), 619-636. 2010th ed. Vol. 86.

Kugler, Peter, and Tobias Straumann. 2020. “International Monetary Regimes: The Bretton Woods System.” In In Handbook of the History of Money and Currency, 665-685.

Laub, Zachary, and James McBride. 2014. “The group of seven (G7).” Council on Foreign Relations, (May). https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/179927/group%20of%20seven.pdf.

Majaski, Christina. “What Is a Trilemma and How Is It Used in Economics? with Example.” Investopedia. Investopedia, October 10, 2022. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/trilemma.asp.

Mundell, Robert. “On the History of the Mundell-Fleming Model – International Monetary Fund.” International Monetary Fund. International Monetary Fund. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.imf.org/External/Pubs/FT/staffp/2000/00-00/mundell.pdf.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Christoph Trebesch. 2016. “The International Monetary Fund: 70 Years of Reinvention.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no. 1 (Winter): 3-28. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257%2Fjep.30.1.3.

“Stability and Growth Pact.” Economy and Finance Europa. Accessed May 1, 2023. https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-and-fiscal-governance/stability-and-g rowth-pact_en.

“The Euro.” European Central Bank, December 22, 2022. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/euro/html/index.en.html.

“Thunder in the air.” Economist, July 21, 1973, 63+. The Economist Historical Archive (accessed April 26, 2023). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/GP4100083117/ECON?u=txshracd2602&sid=bookmar k-ECON&xid=f60eb4b0.

“Two out of Three Ain’t Bad.” The Economist. The Economist Newspaper, August 27, 2016. https://www.economist.com/schools-brief/2016/08/27/two-out-of-three-aint-bad.