8 Production: International Institutions

What happens when a government or state actor commits a treaty violation toward a foreign investor? Do the states handle it on their own? Are foreign investors responsible for fixing the problem themselves? When disputes arise, parties agree to go to arbitration. This is used as a way to solve legal disputes impartially. In the United States, this is why they have a judicial system and due process in the courtroom. However, on an international level there are a lot more factors that come into play regarding legal disputes, not to mention there isn’t a common constitution or shared legal document that can be applied on an international level. Everyone from individual community members to powerful nations can be affected by a dispute between a foreign investor and a state. Leveling the playing field is important for the smaller participants who need legal protections to ensure their voices are heard. It’s also important for countries that are going up against successful billion-dollar companies with vast amounts of resources. International investment treaties were made so countries could set a standard for treatment of foreign investors from other states (Colombia, 2022). If there is a breach of an international investment treaty, the involved parties can bring their grievances to a courtroom. This is the process of investor-state dispute settlement, hereafter referred to as ISDS, which allows private investors and states to settle their disputes on legal matters through arbitration (Colombia, 2022). Courts that handle ISDS claims are responsible for awarding the correct party their remedy usually a financial award – by the violating party (USTR, 2014). Most ISDS claims are brought up by the investors involved and out of those claims filed, a majority were brought in by private investors from developed countries (Colombia, 2022).

Bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) are both parts of the process of investment treaties. BITs ensure that foreign investors in a different country receive fair treatment in regard to private investments that they make in a host country (Cornell, 1992). The ICSID is designed specifically for international disputes (Colombia, 2022). Overall, ISDS including BITs and ICSID are useful systems that create a fair and legal method of settling disputes. They give states the option of what kinds of protection they want to offer to investors. It allows them the opportunity to oversee foreign investors’ grievances in a fair light and builds on the legal system created domestically, encouraging continuity when settling disputes.

The ISDS process is extremely important to international relations. Before, foreign investors would have to risk solving legal disputes with the host country they were in, which meant facing their courts and their laws. These disputes could become disputes between states making them much more politicized. There arose a need for disputes to be handled that would offer protections to investors in host states.

In this chapter, we’ll be discussing how ISDS addresses the problem of legal disputes between state actors and foreign investors. We’ll be looking at the historical background, examples and how we can compare ISDS claims to how the World Trade Organization settles disputes. We’ll also be observing what ISDS accomplishes, notable criticisms of the process, and its relation to multinational companies.

Key Design Features

ICSID

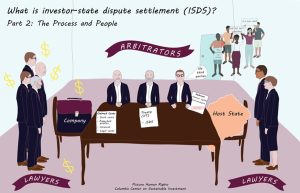

Like most governmental processes, ISDS requires a bureaucratic process of accomplishing its purpose. The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is where countries can resolve investor-state disputes (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). It was created in 1965 in Washington, D.C. where it currently hosts its headquarters. As a member of the World Bank Group, it exists to solve arbitration problems between investors and states (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). So far, more than 150 states have signed and ratified their membership in the agreement. There are four stages to the process of settling these disputes in the ICSID. The first step is the registration and tribunal appointment. Then there is the hearing on the jurisdiction. After that, there is the hearing on merit which can lead to an awarded amount, and lastly, there can be an annulment processed if it is requested. (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010) State consent to arbitration is a key design feature in the functions of the ICSID. In international law, there are legal frameworks that are bypassed through states’ consent. (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010) That way it won’t be necessary to exhaust local remedies and other functions done through international law. Consent can be given through several different methods. It can be given in a government contract, an interstate treaty, or through domestic arbitration law. (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010) Another key design feature of the ICSID is the process of enforcement. Members need to consent or agree to awarding the correct amount within their domestic courts. This means the court can decide in favor of the state, the investor, the suit can be discontinued, or there can be no damages awarded. (UNCTAD, 2021) Whichever direction the case goes, the appropriate party must enforce the court’s decision.

BITs

Bilateral investment treaties are agreements that are signed to establish terms and conditions on an international level for private investments between nations and companies of one state in a different state. (Cornell, 2022) BITs are related to ISDS claims because ISDS suits are filed when BITs have been violated. Countries sign BITs for many reasons. They can sign them to get around weak domestic institutions, or because countries they’re in economic competition with sign BITs. They can also sign them to be perceived as open to foreign investors or to raise the costs of expropriation, inevitably making private investor protections more necessary. (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010) In most cases, countries that sign BITs will get more foreign direct investment (FDI). It can seem like FDIs increase when more BITs are signed, which is generally the case. However, the behavior of states can play a bigger role in that they show BITs follow FDIs. (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010) There is a demand by foreign investors to get into markets and proximity to markets in nearby regions. (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010) Over 2,000 BITs have been signed and there are certain circumstances in which BIT organizers decide to delegate disputes over to the ICSID. This is seen when the private investor’s home country is much more powerful than the host country they were in, or if the home country has a large number of multinational corporations. Also if the host country participated in expropriation within the last decade or if they receive world bank assistance. Disputes can also be delegated if the host country has been independent in the last decade. That is all to say that, BITs are different and unique to the countries they are being applied to. This uniqueness means the effects of the treaties will be different depending on the circumstances. The effects of BITs can also be dependent on the behaviors of those signing. States that end up in international arbitration end up getting fewer FDIs, and if they lose their arbitration dispute they receive even less FDIs.

Background, Example Scenario, and Comparisons

Historical Background

Before ICSID, various governments made attempts to create a system to encourage and protect foreign direct investments. This was difficult given the variety of views governments had when it came to how to handle legal issues that would arise, including who would be best or arbitrate such issues and who would be financially responsible when conflict such as this arose. As mentioned, ICSID was created in 1965 via what is colloquially known as the Washington Convention. Available online, the historical record describes the purpose of the organization as one “to promote the resolution of disputes” through “facilitating recourse to international conciliation and arbitration” (ICSID, n.d.). As a member of the World Bank Group, ICSID was created as part of an international financial institution, becoming a part of a global infrastructure for developing prosperity, especially in developing nations, and reaching a shared understanding with member states. It is currently ratified by 156 states.

Example Scenario

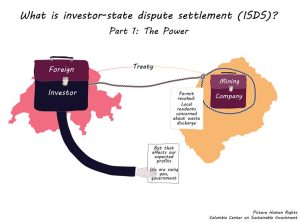

To understand ISDS, let’s take a hypothetical foreign investor – Example Inc. Example Inc. is located in Country A, but is interested in business in Country B, specifically mining, using the ample resources available in Country B that have yet to be developed. When Country A and Country B develop and agree to an investment treaty, they agree to ISDS provisions that provide corporations like Example Inc. standing to sue Country B in the event that Country B takes actions that affect their business and foreign investment. Country A would be Example Inc.’s home state and Country B would be their host state. In theory, this agreement provides Example Inc. opportunities to develop their mining industry and financially prosper, while simultaneously bringing economic development and job opportunities to the people of Country B.

In this scenario, we can understand the FDI into the mining company in Country B to be an investment in the primary sector; that is to say, industries involved in the extraction of raw resources. If it helps your understanding, we could easily imagine the company to be something in the agricultural industry, for instance. However, FDI can be in a variety of industries, such as manufacturing, the service industry, or even banking (Columbia, 2022).

When disputes arise, Example Inc. is allowed to directly arbitrate with Country B instead of needing to rely on their home state, Country A, to act on their behalf. Country B’s citizens may be concerned with environmental conditions worsening because of the development Example Inc. has done in their country. Country B might even have passed environmental legislation at the behest of domestic popular support. However, those environmental protections negatively affect Example Inc. investment in Country B and their business; because Country A and Country B have an investment treaty that includes ISDS provisions, Example Inc. is able to bring a case against Country B, their host state. Although an agreed-upon tribunal to arbitrate the case is involved, this dispute settlement process does not include third parties: Example Inc. and Country B are both directly involved with the arbitration. Unlike other common legal proceedings, third parties have little ability to directly participate or intervene in ISDS (Columbia, 2022). This may be of frustration to citizens and environmental protection groups in Country B, who because of the agreed-upon ISDS provisions in the investment treaty between Country A and Country B, do not have a seat at the table, even if the end result directly impacts their health and livelihoods.

These concerns about environmental protection and human rights violations can be seen in the real world. Ethiopia, a country that receives foreign direct investments in the agricultural sector, has had rising concerns about foreign investors’ use of the country’s water resources. There are also concerns over foreign investors’ efforts (or lack thereof) on environmental protection as well as enforcement of these protections by the government of Ethiopia (Bossio et al., 2012). Blanton and Blanton (2006) found that greater respect for human rights is linked to countries being better hosts for FDIs. However, there are a variety of potential conflicts between economic development and respect for human rights, even if there are reasons to respect human rights as human capital develops (Blanton & Blanton, 2006). For these reasons, more recent investment treaties may specifically include provisions related to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, like Goal 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation (United Nations, n.d.). Beyond that, cases brought forth for arbitration can include topics such as tax evasion and money laundering, addressing climate change, government regulation of health care, and more (Columbia, 2022).

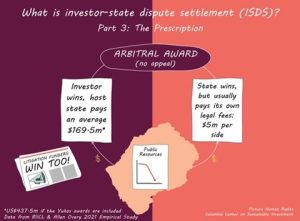

After the arbitrators reach their decision, awards are given out to the winner with no right of appeal. In our scenario, let’s imagine that Example Inc. wins its dispute. Country B would then directly pay Example Inc. in damages as part of their award. Country B could then continue its business as usual in the host state. Notably, this process did not involve Country A having to act on behalf of Example Inc. It is also important to consider that the damages awarded to Example Inc. by Country B would come out of taxpayer dollars; as noted above, these same taxpayers are unlikely to have had a seat at the table when the case was arbitrated. These are also resources that could have been used by the host state in areas such as health and education (Columbia, 2022). How might the citizens of County B react to this arbitration process if they knew their money was being paid out to foreign investors?

In this scenario, we can see that there are concerns about the role in which the people affected by the decisions reached through arbitration often do not have a seat at the table. Additionally, as mentioned previously, home states and to an extent the foreign investors involved can be more powerful than the host countries; this imbalance of power can make it difficult for developing countries to adequately arbitrate against such disputes with large corporations while simultaneously protecting the interests of their citizens. What recourse do developing countries have? Think about the implications that may arise because of this – criticisms of ISDS are explored later in the chapter.

ISDS vs. WTO Dispute Settlement

To better understand the investor-state dispute settlement procedure, it would help to understand it as compared to the dispute settlement procedure of the World Trade Organization, shortened as the WTO, which is another important institution in the study of international political economy. These differences extend beyond the surface level understanding that trade and investment differ. One fundamental difference is that while WTO disputes occur between states, ISDS involves dispute settlements between foreign corporations and states; foreign corporations cannot sue the country they have business with through the WTO, but they can if the investment treaty between their home state and the host state includes ISDS provisions. When disputes arise because of WTO violations, it becomes an international legal process through the WTO, arbitrated between states. Through that, we can understand that elements of power politics, both on an international scale and domestic interests, come into play when these types of disputes are arbitrated; examples of this can be seen with India and Brazil as emerging powers (see Mahrenbach, 2016). By comparison, ISDS involves arbitration between states and corporations. While ICSID provides a legal framework for agreed-upon rules and arbitration processes, a variety of international tribunals may come into play throughout the dispute settlement process. Importantly, this means that the home state does not have to get involved on the corporation’s behalf, which could raise a variety of international political implications and politicization. The politicization of investment treaty disputes is an area of research that warrants further study (see Gertz and Poulsen, 2018).

Further comparing ISDS with the WTO dispute settlement process, we can explore how often each method is used. Since its inception in 1995, the WTO generally has seen a decline in requests for the establishment of a panel to arbitrate disputes (Mavroidis & Johannesson, 2017). The number of treaty-based ISDS cases has continued to rise over the same time period (UNCTAD, 2021). ISDS cases have also accumulated rapidly over the past 10 years (Columbia, 2022). It is important to remind readers that WTO’s dispute settlement process and the ISDS process must be carefully compared given the differences in scope and jurisdiction. There are also simply more corporations able to bring forth cases for arbitration than there are countries bringing forth WTO violations. However, noticing trends for both helps us to better understand the ever-changing international financial institutions and political climate. Investment and trade go hand in hand when it comes to the global economy.

ISDS Implications

Purpose and Critics

The purpose of ISDS is to peacefully resolve trade conflicts between host states and multinational corporations. ISDS permits international investors to resolve differences with the government of a host state in which their investment was made in a neutral venue through a binding international tribunal. Without ISDS foreign investors would have to rely on local or state courts of the host country to resolve conflicts. Investors would face obstacles such as a lack of legal safeguards and of judicial independence because courts would make biased decisions in favor of the host country. On the other hand, ISDS has had to face criticism in regards to how it’s being applied. Though the goal of ISDS is to stay neutral, many critics have expressed their concerns that private investors have exploited the ISDS clause. Critics believe that successful investors with over 1 billion in annual revenue or high-income countries tend to file for claims (Columbia, 2022). Hence countries that have lower incomes aren’t financially able to file claims or even defend themselves because the loss of a case can have a significant impact on their economy. With that being said, developing countries tend to be victims of ISDS because they are an easy target for exploitation from multinational companies. Another criticism that ISDS faces is that most of the case hearings happen behind closed doors and third parties are not taken into consideration (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010). ISDS cases are decided by three-judge panels nominated and compensated by the investor and responding state, things such as human rights, workers’ rights, and community rights are not considered while deciding these cases. Treaties mostly impose binding obligations only on states, not investors; states generally cannot initiate or bring counterclaims in ISDS. So an investor may win a case even if it has violated domestic law, international human rights, or environmental norms in connection with the operation of the investment. With that being said, the most important thing that is considered while deciding an ISDS case is if principles of the appropriate investment treaty are used.

Who is Affected by ISDS?

ISDS has a lot of leverage and can have negative implications because environmental and human rights aren’t considered when passing judgments. All things considered, the general public tends to be collateral damage. An example of this is the case that occurred in 2009 between Chevron v. Ecuador. Chevron filed a case against Ecuador under a BIT in order to avoid the payment of a multi-billion dollar court decision against the firm for the massive degradation of the Amazon rainforest. The Ecuadorian government discovered that their investor Chevron had been dumping toxic waste in the water, as well as digging hundreds of open-air oil sludge pits in Ecuador’s Amazon, leading to contaminating the communities of approximately 30,000 residents. Rather than complying with the orders of the Ecuadorian government, Chevron requested that the investor-state court review the decision that was made. Chevron also requested the court to force Ecuador’s taxpayers to pay billions of dollars in damages it may be required to pay to clean up the still-devastated Amazon, as well as all legal bills paid by the corporation in its investor-state dispute settlement. Chevron’s investor-state action seeks to re-litigate crucial points of the protracted domestic court case, including whether the affected communities had the right to challenge the firm in the first place (Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, 2015). Considering the environmental damage that Chevron had caused in the Ecuadorian community, Chevron is still able to file a case under the ISDS because the trade treaties have been “violated”, disregarding the fact that the company has caused a lot of environmental damage. Furthermore, because of the company’s actions, indigenous communities living in that region of the Amazon virtually went extinct (Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, 2015). This case shows that even though the treaty was made with good intentions, multinational companies have used ISDS to assist themselves resulting in the victimization of common people.

COVID-19 has heavily impacted ISDS as most states may not be able to comply with investment treaties that were made before COVID-19. Investors can easily sue host states as they are bound by their investment treaty. New rules and regulations would have to be placed in order to preserve public health and ensure economic recovery. There have been multiple attempts to suspend treaty-based investor-state litigation for all COVID-19-related measures or establish the use of international law defenses in these rare circumstances because the primary goal should be to focus on the global crisis we are facing as a world rather than focus on investment treaties. There have also been many instances in the past where ISDS has had a negative impact because it puts countries in a difficult position where they have to decide whether they use their resources to defend themselves against a lawsuit or to help their civilians in a time of crisis. With this in consideration, and also understanding the severity of the situation around COVID-19, some measures have been taken in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) drafted the proposed agreement for the coordinated suspension of ISDS in April 2020 with respect to COVID-19-related actions and disputes. The agreement is a provision of any investment treaty in effect between two or more signatories to this agreement providing for the resolution of disputes between an investor and a state is thus suspended with regard to claims that the responding signatory state believes to be concerning COVID-19-related measures (Bernasconi-Osterwalder & Maina, 2020). The treaty also mentions that “any indicator preventing or detection of virus transmission; ensuring the availability of tangible and intangible goods, services, materials, or technology; or national economic recovery, stability, or development during or following the spread of the virus and the international response; as well as any other objective relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences” (Bernasconi-Osterwalder & Maina, 2020). Though certain measures have been taken to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and to help states during hard times, there are still many states that are struggling with ISDS cases from the past that are yet to be resolved.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ISDS is a system of protection for private investors and states. Its primary goal is to provide a legal system for settling disputes between foreign investors and states. Bilateral investment treaties are the primary way in which investors and states agree to terms on foreign investment. ICSID, as a part of the World Bank Group, helps facilitate these investment treaties and provides a framework for arbitration and enforcement. Overall, this system has the intention to develop prosperity, especially for developing nations which often act as host states for foreign investment.

Though ISDS was made with good intentions and provides protection for both parties, throughout the years there have been concerns raised about the balance of power between large corporations and the developing countries they’re investing in. With developing countries being limited in legal resources and recourse to uplift the interests of their citizens on issues like environmental protection and human rights even if it risks arbitration with the foreign investors in the country who claim to be negatively impacted by such interests. Because of these considerations, ISDS has received criticism as a system that benefits private investors at the expense of developing countries and their citizens. Additionally, damages being paid out from the host state to the foreign investors in the event the host state loses the arbitration process is one aspect of ISDS that has the potential to be politicized.

Countries that host foreign investment and agree to ISDS provisions must carefully balance domestic interests and foreign investors’ interests. COVID-19 especially has shown how investment agreements are complicated as situations in the host countries evolve and the state balances domestic concerns with foreign interests; states navigating domestic concerns of public health may be doing so at the risk of challenging agreed-upon terms for foreign investments. States agree to the enforcement of ISDS provisions when signing investment treaties while understanding that the domestic situation may change outside of their control but will nonetheless impact foreign investment and the agreed-upon terms. There are questions raised as to the role of global institutions in intervening in situations like this, even if the agreement is between a corporation and a state and not a state-to-state agreement.

Future research might explore how ISDS provisions between states continue to evolve. Although this chapter focused primarily on FDI between a developed home state and a developing host state, investment treaties also exist between developed states. As the global economy develops and developing countries continue to industrialize and move past primary sectors, there are additional considerations for the kinds of foreign investments received and how that may impact the host state’s citizens. This chapter has mentioned concerns about environmental impact and human rights as a part of foreign investment; future research into the treaties themselves and the effectiveness of including specific provisions around the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals might yield interesting insights into this area. Generally speaking, the effectiveness of BITs and the arbitration methods provided by ISDS is an area of research that could use more study, exploring the effectiveness of ISDS and how it affects relationships between states when provisions are broken.

ISDS is a novelty amongst international institutions that generally involves disputes between states. As such, as international financial institutions evolve with shifting international politics, so too will the scope and specific provisions of ISDS evolve as countries become more experienced with this type of dispute settlement process and citizens continue to raise concerns about the ways in which countries agree to foreign investments.

Works Cited

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2010). Delegating differences: Bilateral investment treaties and bargaining over dispute resolution provisions. OUP Academic. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://academic.oup.com/isq/article/54/1/1/1789480?login=true

Bernasconi-Osterwalder, N., Brewin, S., & Maina, N. (2020). Protecting Against Investor–State Claims Amidst COVID-19: A call to action for governments. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/investor-state-claims-covid-19.pdf

Beunder, A., & Mast, J. (2019). As the world meets to discuss ISDS, many fear meaningless reforms. Longreads. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://longreads.tni.org/isdsmany-fear-meaningless-reforms

Blanton, & Blanton, R. G. (2006). Human Rights and Foreign Direct Investment: A Two-Stage Analysis. Business & Society, 45(4), 464–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650306293392

Bossio, D., Erkossa, T., Dile, Y., McCartney, M., Killiches, F., & Hoff, H. (2012). Water Implications of Foreign Direct Investment in Ethiopia’s Agricultural Sector. Water Alternatives, 5(2), 223–242.

FitzGerald, A. G., & Valasek, M. J., (2017). Frequently asked questions about investor-state dispute settlement. Norton Rose Fulbright. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/8014c6b7/frequently-asked-questions-about-investor-state-dispute-settlement

Gertz, G., Jandhyala, S., & Poulsen, L. N. S. (2018). Legalization, diplomacy, and development: Do investment treaties de-politicize investment disputes? World Development, 107, 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.023

Investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). (n.d.) Picture Human Rights. Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.picturehumanrights.org/isds

ISDS: Important questions and answers. United States Trade Representative. (n.d.). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/blog/2014/March/Facts-Investor-State%20Dispute-Settlement-Safeguarding-Public-Interest-Protecting-Investors

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Bilateral Investment Treaty. Cornell Law School. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/bilateral_investment_treaty

Mahrenbach, L., C. (2016). Emerging Powers, Domestic Politics, and WTO Dispute Settlement Reform. International Negotiation, 21(2), 233–266. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718069-12341332

Mavroidis, P. C., & Johannesson, L. (2017). The WTO Dispute Settlement System 1995-2016: A Data Set and its Descriptive Statistics. Journal of World Trade, 51 (Issue 3), 357–408. https://doi.org/10.54648/trad2017015

Primer on International Investment Treaties and Investor-State Dispute Settlement. (2022). Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://ccsi.columbia.edu/content/primer-international-investment-treaties-and-investor-state-dispute-settlement

Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. (2015) Case studies: Investor-state attacks on … – public citizen. Case Studies: Investor-State Attacks on Public Interest Policies. Public Citizen. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/egregious-investor-state-attacks-casestudies_4.pdf

The facts on Investor-State Dispute Settlement. (2014) United States Trade Representative. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/blog/2014/March/Facts-Investor-State%20Dispute-Settlement-Safeguarding-Public-Interest-Protecting-Investors

The History of the ICSID Convention. (n.d.). International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://icsid.worldbank.org/resources/publications/the-history-of-the-icsid-convention

UNCTAD. (2021) Investment flows to developed economies slumped by 58% in 2020. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://unctad.org/press-material/investment-flows-developed-economiesslumped-58-2020

UNCTAD. (2021) Investor-State Dispute Settlement Cases: Facts and Figures 2020. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaepcbinf2021d7_en.pdf

United Nations. (n.d.). The 17 goals | sustainable development. United Nations. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals