4 Trade: Political Institutions

Previous chapters have addressed some of the major considerations of international trade policy: international institutions, interest groups, and the economic impacts of trade. However, none of these elements are responsible for directly creating trade policy. That responsibility falls on national governments, and the domestic politicians responsible for drafting and ratifying trade legislation. Understanding this political process of trade policymaking will help us answer some of the fundamental questions of IPE: what is the political function of trade policy? Why does trade policy vary so much between countries and time periods? And, if free trade is good for countries as a whole, why does every country still have barriers to trade?

In this chapter, we’ll go over the political motives and institutions that shape how policymakers create trade policy, as well as the reasons for why different sets of policymakers might seek different levels of trade. We’ll also look at some of the theories that scholars have made to explain the process of setting trade policy, and what might cause a country to turn either more liberal or more protectionist over time. Broadly, these theories fall into three main groups, depending on the primary factor that is assumed to control the direction of trade policy. These three factors are: interests, institutions, and international dependency.

Interest Groups and Trade Policy

The previous chapter covered how unequal gains from trade can create winners and losers from international trade on a subnational level. This creates an incentive for interest groups to form for the purpose of protecting their economic interests. Naturally, scholars have looked to these interest groups as a major factor in deciding the direction of trade policy. However, these interest groups don’t get to write the trade policy themselves. Rather, they need to get national politicians to write their preferred trade policy into law. This then raises the question: if free trade benefits are so great, why would national politicians listen to a protectionist minority?

The answer, according to some political economists, lies in a fundamental characteristic of democratic systems: campaigns that spend more tend to win more. Whether it’s through buying ad space, hiring campaign staff, or holding rallies, politicians with more funding to spend are typically able to outperform their rivals (OpenSecrets 2022). This creates an incentive for politicians to seek sources of campaign financing, a role that interest groups are willing to play.

Endogenous Tariff Theory

First outlined by Magee, Brock, and Young in their book “Black Hole Tariffs and Endogenous Trade Policy” (Magee, Brock, and Young 1989), and expanded upon by Grossman and Helpman in their paper “Protection for Sale” (Grossman and Helpman 1994), Endogenous Tariff Theory (ETT) models the trade policy space as an auction, with the government setting trade policy in response to the amount of contribution given by different (factor-ownership) lobbies. Lobbies contribute not only to protect their own industries but to protect themselves from the lobbying of other industries, while governments are only concerned with maximizing total contribution in relation to aggregate welfare (finance & popularity). This creates an equilibrium tariff rate, where the government sets tariffs at the level which will get them the highest level of political funding without harming the economy or angering consumers too much.

ETT and Variation over Time

If interest groups are the controlling factor in setting tariff levels, how do we explain shifts in trade policy, both towards more liberalization and more protectionism? ETT predicts an “equilibrium” tariff decided by market forces, yet as we’ve seen in previous chapters, tariff levels declined significantly over the latter half of the 20th century, before seeing a resurgence of protectionism in the 2010s. How can we explain this seeming discrepancy? One possibility is that policymakers have found new policies to satisfy demands for protection beyond high tariffs, and another is that the makeup and preferences of interest groups have simply changed over time.

Policy Substitution

While tariff rates have dropped precipitously since the mid-20th century, this doesn’t necessarily imply that countries are fully moving towards free trade. Instead, we’ve seen a rise in the use of non-tariff barriers to trade which skirt around agreements prohibiting the use of protectionist trade measures. While this term includes traditional elements like quotas and anti-dumping measures, an increasingly widespread form of non-tariff barriers has been excessively stringent regulations which implicitly discriminate against foreign products (Staiger & Sykes 11). These “Red Tape Barriers” as Maggi et al. (2022) puts it, have filled much of the same role as high tariffs did in the past, providing protection to interest groups that lobby for it. Therefore, despite the seeming move towards trade liberalization, the fundamental principles of ETT might still hold true, just with copious amounts of “red tape” as the outcome rather than high tariffs.

Another possibility is that policymakers found a way to compensate the losers of free trade while simultaneously lowering trade barriers. This is the explanation put forward by the embedded liberalism thesis, which posits that the rise in social welfare programs in developed countries during the mid-20th century was in part an effort to ameliorate the distributive effects of trade liberalization. Survey research has shown that these compensatory programs do in fact lead to higher support for free trade, and it could be that the shift towards trade liberalization was due to the substitution of compensation for protection by policymakers (Ehrlich & Hearn 2014, Kim & Pelc 2021).

On the other hand, the stalling or rollback of many of these redistributive programs even as tariffs continued to liberalize throughout the 1990s and 2000s, created a mismatch between the demands for protection or compensation, and the provision of it. Gawande et al. (2021) attributes this gap as the primary driver of the anti-free trade backlash and the “China Shock”. Evidence from the 2016 election seems to back up this view, as districts which received compensation for losses from trade supported Trump’s populist, protectionist stance significantly less than comparable districts that didn’t receive compensation (Ritchie & You 2021).

Preference Shift

Another explanation for shifts in trade policy over time could be that shifting preferences on trade can lead to either increasing liberalization or protectionism. While ETT follows the HOSS model in assuming that factor ownership is the primary determinant in deciding whether an interest group is in favor of protectionism or free trade, recent scholarship has shown that the reality of lobbying is often more nuanced.

In particular, the relative productivity of certain firms can affect their support for protectionism. Firms that are highly productive often support lowering trade barriers since they expect that their advantage in productivity will allow them to benefit from expanded access to the international market (Kim 2017). As will be covered in later chapters, it is often only the most productive companies in an industry which are able to successfully expand worldwide, and it’s these multinational-corporations-to-be which form a crucial pro-liberalization lobby (Plouffe 2017). This suggests that the shift towards liberalization can in part be explained by shifts in productivity, as firms which grew relatively more productive began to prefer trade liberalization enough to overcome the protectionist lobby and get their preferred tariff level.

Preferences can also shift the other way, however, and scholars have also looked at how the recent surge of protectionism can be explained by shifts in interest group preferences. In a recent paper, Grossman and Helpman revisit their earlier model, but this time includes the effects of populism on group identity. In this model, while normally group identification follows factor ownership as in the HOSS model, rising political populism can lead voters to identify with interest groups that they have no direct economic stake in. As an example, think of a suburban Trump voter who, despite having no economic interests in common with a Rust Belt auto worker, still votes in favor of protecting their industry. According to Grossman and Helpman, as populism increases, interest groups realign, with the overall effect of increasing the equilibrium tariff rate (Grossman and Helpman 2021)

Additionally, while the ETT model expects interest groups to act rationally in their own economic best interests, it’s fairly evident that this isn’t always the case. Aaken and Kurtz highlight three cognitive biases that affect how people think about trade: first, loss aversion leads people experience the losses from trade much more acutely than the gains. Second, even voters that are completely unaffected by trade liberalization can still perceive it as a loss, as they were led to expect an economic benefit by politicians and economists advocating for free trade and feel disappointed if it doesn’t materialize. Third, Aaken and Kurtz highlight a “double-loss frame” where voters in rich countries perceive the rise in inequality because of uneven gains from trade as being compounded by decreasing global inequality (Aaken & Kurtz 2019). In combination, these factors can lead to an increase in demand for protectionism, even as trade liberalization creates gains for the economy as a whole.

ETT and Variation across Countries

Assuming that special interests are the driving force behind trade policy, this would lead us to conclude that the main reason why trade policy differs between countries is due to how interests are aggregated in the national political system. While politicians might serve at the national level, they aren’t always elected by a national vote. Here in the US, the size and makeup of a politician’s constituency, or the group of people who actually vote for them, can vary dramatically depending on the office. Senators, for example, have constituencies which span entire states, while the constituency of a House Representative might not even cover a single city. This has led political economists to focus on two things to explain regional and national variations in trade policy: geographical concentration of industry, and differences between electoral systems. As we’ll see, the conclusions drawn from this research have been somewhat mixed.

Geographical concentration of industries

The first proposition to discuss is somewhat straightforward: industries which are concentrated geographically are more successful in getting protection, since they have an easier time organizing for collective action and can focus their lobbying efforts on a relatively small number of politicians. Pincus (1975) found as much in a study of US tariff policy in the 1820s, although he noted that highly dispersed industries also had an advantage by dint of being able to influence a few politicians in different states. Evidence for the effectiveness of concentrated industries has been borne out in more recent research. In a cross-national study, Ardeleans and Evans (2013) found that geographically concentrated industries were able to maintain higher tariff levels for their products. The picture is muddled somewhat by Saha (2019), whose research on trade lobbying in India found that while in general, geographical concentration increased lobbying effectiveness, for industries with highly substitutable products, the effect actually went the other way. Firms which were geographically concentrated but produced highly similar products ended up facing too much competitive pressure to effectively organize, inhibiting their ability to lobby effectively.

Electoral Systems

Unfortunately, this is where things begin to become a lot less clear. While a number of prominent scholars have focused their research on examining the relationship between electoral systems and trade policy, the wide variety of government structures around the world have led to a number of different electoral institutions being identified as having an effect on trade policy. Even worse, for many of these institutions political economists have come away with multiple and often contradictory views on their relationship with trade policy.

District Size

District size, or constituency size, simply refers to how large a politician’s home district is, in terms of population (and/or geographical area). Generally, political economists consider industries located in smaller districts to have an easier time lobbying for protection, and politicians elected from smaller districts as being more susceptible to protectionist lobbying. The logic is simple: the smaller the district, the more likely that a narrow interest group can represent a sizable portion of a politician’s constituency. Several empirical tests have borne this out, finding that larger districts are associated with lower levels of protectionism (Rickard 2014).

Presidential vs. Parliamentary Systems

Presidential systems refer to those with a directly elected executive (the President), as is found in countries like the United States and France. Parliamentary systems refer to those where the executive (the Prime Minister) is chosen by the legislature, as are found in countries like the United Kingdom and Japan. Political economists have generally ascribed higher levels of protectionism to Parliamentary systems, with the logic being that since Prime Ministers are ultimately answerable to a group of legislators elected from small, subnational districts, they are more susceptible to interest group lobbying than Presidents which are elected by a national constituency. Additionally, Presidents are viewed as more powerful in their own right than Prime Ministers, granting them further latitude to pursue their own policy goals, especially in the realm of foreign policy. This adds a further layer of separation between Presidents and the pressures of interest groups.

Electoral Rule

Perhaps the most complicated debate regarding the effect of electoral institutions on trade policy has to do with the issue of majoritarianism versus proportional representation. Majoritarianism refers to the practice of only assigning district seats to the party that wins the most votes in that district, as is the case in the US and UK. Proportional Representation (PR) involves the election of multiple members from each district, with seats assigned proportionally to the votes a party receives. For example, in a three-way split of votes in a 10-member district with Party A receiving 30%, Party B receiving 30%, and Party C receiving 40%, the parties would each receive 3, 3, and 4 seats respectively. Contrast this with the majoritarian system, where only Party C would receive a seat at all. This difference is why PR countries tend to feature multi-party governments, while majoritarian countries like the US tend towards having two-party systems, since only the two biggest parties have any chance of winning seats.

Scholars are divided on whether majoritarian or PR systems generate more protectionist policy, with the empirical findings being similarly split. On the one hand, majoritarianism results in smaller margins of victory, as the two parties need to fight over a narrow number of swing districts to get control of the government. This could lead politicians to favor the narrow protectionist interests of swing voters over the broader welfare of the population (Roelfsema 2003). Indeed, there have been several studies finding that majoritarian countries tend to have higher tariff levels than PR countries (Rickard 2014). By the same token, parties in PR systems don’t have to win certain districts to gain control, they just need to collect as many votes as possible overall. This could help immunize PR politicians from protectionist lobbying, as they are no longer reliant on the support of small but concentrated interest groups to win certain districts.

On the other hand, some scholars have argued that the close margin of victory in majoritarian systems actually decreases protectionism, since losing even a small number of votes can cost a politician their seat. This essentially negates the collective action problem faced by consumer interests when organizing against protectionist interest groups, since even a relatively small number of uncoordinated consumers voting against a protectionist politician can cost them their election. Yu (2009) provides some evidence for this, finding that when the Democratic Party advocated for higher tariffs and protectionism, it ended up worse-off despite the increase in interest group contributions, since this gain was more than offset by the defection of unaffiliated voters. Pinheiro (2013) finds similarly that due to the small number of votes needed to swing control of government, majoritarian systems are expected to generate more liberal trade policy.

Access Points

Access Points Theory represents an effort to resolve the seemingly contradictory relationship between electoral rule and trade policy. Instead, the important factor in deciding the level of protectionism or liberalization is the number of “access points” present in a political system, or the number of policymakers that have an impact on trade policy. Notably, this doesn’t refer to all policymakers in government, only those that have a hand in drafting and ratifying trade legislation. The larger the number of access points, the cheaper lobbying becomes, as interest groups face less competition for influence over certain policymakers, resulting in more protectionist trade policy. Ehrlich (2007) found that, when controlling for this factor, the difference between PR and majoritarian systems disappears, suggesting that electoral rule might not actually be a factor in determining the direction of trade policy.

Institutions and Trade Policy

While interest groups and electoral systems can play a role in deciding who gets elected to office, this is only the beginning of the policymaking process. One of the criticisms leveled at Endogenous Tariff Theory by neo-institutionalist scholars was that it assumed that government is simply a reflection of societal interests, with no interests of its own. However, the policymaking process is much more complex than a simple aggregation of political preferences, and legislation needs to pass through a multitude of rules and institutions before it becomes law. We’ll look at some of these institutional rules and features, how they can affect trade policy, and how changes in political institutions can change policy, even when political preferences remain constant.

Political Parties

Political parties are commonly understood to represent groupings of like-minded politicians with similar stances on certain issues. However, entrenched and long-standing political parties like those found in the US are institutions unto themselves, delegating resources and corralling legislative votes with the goal of maximizing their electoral success. Party discipline refers to the ability of a political party to keep all of its members voting in the same way on legislation, with stronger parties able to pass policy that benefits the electoral chances of the party on the national level. Grossman and Helpman (2005) and Hankla (2006) both argue that the stronger the political party, the more liberal the trade policy that results, as party leaders are able to keep individual members from voting based on their own districts’ economic interests and instead target trade policy that benefits the nation as a whole. McGillivray (1997) deviates slightly from this, finding instead that high party discipline in majoritarian systems instead results in protectionism being concentrated on industries located in marginal swing districts, while low party discipline instead results in higher protection for large industries dispersed across a wide number of electoral districts.

Political parties can also influence voter preference on trade, somewhat reversing the interest group model. Often voters lack information on particular pieces of trade policy, and they may look to political parties to provide cues on the benefits or harms of a particular piece of trade legislation. For example, Hicks et al. (2014) found that party signaling likely played the deciding role in the passage of the CAFTA-DR trade agreement in Costa Rica, inducing voters who would otherwise likely have opposed the trade agreement based on the interest group model to instead support the legislation.

Procedural Rules and Authorities

As anybody that’s competed in parliamentary debate or watched Schoolhouse Rock will tell you, drafting and passing legislation is not as simple as members voicing their preferences and writing them down. Legislation is passed through a highly structured system of rules and procedures before it becomes a law, and changes in these rules and procedures can dramatically impact the character of the policy that results. We’ll look at a few of these rules, and how they affect the direction of trade policy.

Agenda-setting power refers to the authority to decide which legislation can be put up for debate. While the holder of agenda-setting power can’t ultimately decide what kind of legislation gets passed, they are able to frame the debate around their preferred policy. When it comes to trade policy, agenda-setting power is relevant if the particular office that holds that power has a structural preference either for more protectionism or liberalization, as this will lead to either more protectionist or more liberal policy coming up for ratification.

Veto points refer to points in the legislative process where an actor can exercise their ability to either reverse a decision or completely shut down debate. Like agenda-setting power, veto power doesn’t help a policymaker pass their preferred policy, but it does allow them to block policies which deviate from their preferred policy too much, to an extent. The more veto points present in a system, the harder it is to significantly change the direction of policy, which on the one hand might make it harder to break out of a protectionist status quo but might also protect a liberal trade policy from demands for protectionism (O’Reilly 2003).

The last procedural rule has to do with delegation of authority to make trade policy between the legislative and executive branches. It is often assumed by political economists that legislatures demonstrate a structural tendency towards higher levels of protectionism than executives, for a number of reasons. First, individual legislators are elected by subnational districts, and as has been said before, larger districts are generally associated with preference for liberal trade policy. Second, executives (heads of government and heads of state), are typically charged with handling foreign relations, and it has been suggested that focusing on trade policy as foreign policy leads to a preference for liberalization, as lowering domestic tariffs can be used as an incentive for foreign countries to provide concessions in return. Here in the US, the power to make trade policy has been traditionally vested in Congress. The shift of this authority to make trade policy from the legislative to the executive branch has been characterized as a turning point in American trade policy by some scholars, and we’ll be looking at it as a case study.

Case Study: Smoot-Hawley & RTAA

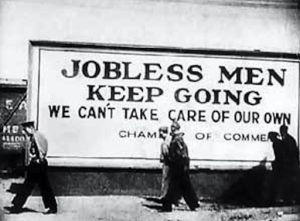

In 1930, Congress passed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, largely as a protectionist measure to provide a boost to the American economy in response to the Great Depression. The Act raised US tariffs to an incredible average of 60%, touching off a trade war as other countries raised tariffs on US products in retaliation. The Smoot-Hawley Act was the pinnacle of a trend in US tariff policy that had been going on for the past century. Throughout the 19th century and into the early 20th century, Congress retained full control over US tariff policy, which resulted in tariff levels depending largely on the preferences of the party in power.

Since the Democrats represented sectors like Southern agriculture which preferred low tariffs and more international trade, while the Republicans represented manufacturing interests which preferred high tariffs to undercut foreign competition, tariff levels would shift up or down whenever control of government changed hands. From 1846 to 1934, about a century, Democrats consistently reduced tariffs while in control of government, while Republicans consistently raised tariffs (Bailey et al. 1997).

In part due to the collapse in international trade as a result of the Smoot-Hawley Act, the US economy was well into the Great Depression by the time of the 1932 election. The governing Republicans were soundly beaten, and Democrats gained unified control of both the Presidency and Congress. This time, however, instead of the typical flat tariff cuts, the Democrats implemented a novel policy known as the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) in 1934. The RTAA did two new things: first, it authorized the President to make tariff cuts only in connection with reciprocal cuts in foreign governments, and second, it set the bar for ratification for these tariff treaties at a simple majority vote, rather than the two-thirds supermajority typically required for ratifying foreign treaties under the Constitution.

(Insert Figure 2 here)

Following the passage of the RTAA, the US would go on to steadily reduce its tariff rates in reciprocation with other countries, leading into the durable trend of post-WWII tariff reductions that has been covered in previous chapters. Some scholars have credited the RTAA with enabling this dramatic about-face in US tariff policy, pointing to its simple yet effective institutional changes as creating the environment necessary for durable trade liberalization. So, why do institutionalist scholars think that these changes were so effective?

What made RTAA durable?

The first major change was the replacement of logrolling in trade policymaking. Before the RTAA, tariff policy was created in a process known as logrolling, where support for the tariff law would be solicited from individual members, who would make their support conditional on the final law accommodating their own interests. As you might imagine, this led to a high level of overall protectionism, as each member would request a high tariff for their district’s primary industry (Nelson 1989). The RTAA put an end to this logrolling by delegating the creation of tariff policy to the executive branch. Post-RTAA, tariff treaties would be negotiated by the President with foreign countries, then would be presented to Congress for a simple up-or-down vote. This undercut the lobbying power of protectionist interest groups, as industries now had to secure the support of a majority of Congress for protectionism, a much harder task than lobbying individual legislators. This was made harder by the fact that the delegation of power to the President enabled them to pick and choose which products to pursue tariff cuts on. This agenda-setting power allowed the President to present Congress with tariff treaties that they knew would not trigger enough opposition for the protectionist lobbies to mobilize a majority (Goldstein & Gulotty 2014).

The second change that RTAA made was the introduction of reciprocal cuts. Bailey et al. (1997) argue that these cuts were much more effective than the previous unilateral tariff cuts that had been undertaken by the Democrats, since they widened the space of acceptable policy options. To model this, they start from two assumptions: Democrats want relatively low tariffs while Republicans want relatively high tariffs, and both want foreign tariffs to be as low as possible. The logic for this is fairly straightforward – each party has their own tariff preferences for the reasons listed previously, and lowering foreign tariffs provides a strict benefit to the US economy by boosting the appeal of US exports abroad. The key insight here is that because US policymakers of both parties wanted low foreign tariffs, they were willing to trade off some amount of deviation from their ideal domestic tariff rate in return for cuts to foreign tariffs on US goods. This creates a situation where, even if Republicans regained control of government, they would still prefer to keep the RTAA tariff levels, because unilaterally increasing US tariff levels would increase foreign tariff levels as well, and while Republicans would still prefer to raise US tariffs, they’re not willing to give up the low foreign tariffs to do so.

The third change was the reframing of trade policy into a foreign policy issue. While the responsibility for setting trade policy was held in Congress, tariff laws were generally treated as domestic economic policy, with the costs and benefits framed in terms of American industry. The passage of RTAA moved that responsibility into the executive office, right before the Second World War and the Cold War turned the orientation of American policy decisively outward. Trade policy was rolled into foreign policy and defense policy in the office of the President, and the RTAA became a tool for the US to secure its economic ties with its allies and partners around the world (Nelson 1989).

Of course, while the RTAA has been hailed as a successful example of institutional reform leading to durable trade liberalization, not all political economists agree with this assessment. Hiscox (1999) argues that the RTAA’s durability didn’t come from its institutional changes, but rather from fortunate timing. He argues that the RTAA only survived because while the Republicans fully intended to overturn it the next chance they had, they would only return to power in 1952, by which time the Cold War and the post-WWII US export boom made a return to protectionism a political non-starter. Furthermore, the RTAA came at the beginning of a long period of political coalition shifting around trade. While before the RTAA Democrats had been consistently pro-free trade and Republicans had been consistently protectionist, over the latter half of the 20th century, party coalitions shifted to such an extent that the parties basically flipped completely, with the Democrats becoming the party of protectionism while the Republicans advocated for free trade. In the interim, both parties ended up internally split on the issue of trade to such an extent that neither could muster up any serious protectionist opposition to the RTAA. Oatley (1999) adds onto this by pointing to the creation of the GATT as the key factor in creating the long-term trend of tariff cuts, arguing that the GATT, not the RTAA, was the real stabilizing factor in American trade politics.

So, was the success of the RTAA real, or was it simply the result of lucky timing? It’s hard to know for sure, but one view might be that while the RTAA did not directly cause the long-term trend of tariff liberalization, it laid the necessary groundwork for it through its institutional reforms (Nelson 1989). In other words, the RTAA was simply the right policy at the right time.

Political Regimes

Most of the chapter so far has centered around explaining the process of trade policy in democratic systems. Yet, of course, democratic governments are not the only type of political regime in the world. Free trade is often associated with democracies, with liberal democracy and trade liberalization sharing the same intellectual roots. Yet, how true is this, actually? Are there concrete reasons for democracies to engage in more or less trade liberalization?

The orthodox argument on political regimes and trade liberalization frames free trade as a public good, benefiting the whole of society over the interests of a narrow few. From that assumption, the conclusion is drawn that, since democracies are more responsive to the interests of their citizens, then they should engage in more trade liberalization. However, Betz & Pond (2019) find no evidence for an increased concern for consumer welfare in democracies than autocracies. They posit that autocrats might actually care more about the economic welfare of the nation, since they draw at least some part of their legitimacy from creating economic stability. Instead, Betz & Pond propose that democracies might engage in more free trade due to the presence of powerful multinational corporations and other pro-free trade lobbies.

Alternatively, the representative nature of democracies might actually make them more susceptible to protectionism. The argument goes that by making government beholden to coalitions of protectionist interests, democracies can entrench protectionist trade policy. Zissimos (2017) finds a complex relationship between democratization and trade liberalization in the context of factor ownership and finds that democratization can result in higher protectionism if the political elite owns the relatively abundant factor. On the other hand, when the elite own the scarce factor, democratization and trade liberalization are positively correlated, as the desire from the masses for a more liberal trade policy leads them to push for increased representation in government. Interestingly, Zissimos finds that when elites in autocracies are owners of the scarce factor, they can use trade liberalization as a method of appeasing the masses and staving off democratization.

Conclusion

On the face of it, the process of making trade policy seems relatively straightforward. A piece of legislation, or an international treaty, is drafted and negotiated, before being presented to a legislative body that chooses either to ratify or not to ratify. Much of the complexity arises in trying to explain why certain trade policies are written in certain ways, why some trade policies fail and others don’t, and what the commonalities between different trade policies are. Unfortunately, politics, and especially trade politics, does not lend itself to easy examination. The actors involved often don’t elaborate on their motives, and even those that do typically have an incentive to conceal their true position. Ultimately, political economists are left to try and infer these hidden causes from what they can see- the end product of either protectionism or liberalization. It should therefore be no surprise that scholars have landed on so many different theories and models to explain the process of making trade policy, and little surprise that so many of their conclusions contradict one another.

At the end of the day, however, political economists might disagree on which element is the most important when it comes to the politics of trade policy, the three main areas of causation that research has clustered around: interest groups, institutions, and interdependence, each highlight an important element in the process of making trade policy. Interest groups absorb the distributional impacts of free trade and communicate those economic impacts to policymakers through lobbying. Domestic political institutions shape how laws are passed, and whose preferences end up shaping trade policy. International interdependence reflects the fluid border between domestic politics and international politics, demonstrating how neither can be taken in isolation.

There is still much more research to be done, and even as the field progresses, real-world events continue to complicate the picture. During the 1980s and 1990s, when most of the initial theorizing was being done, the primary dilemma was over the unprecedented success of trade liberalization- how could political economists explain the sudden shift from decades of staunch protectionism to a steady, almost universal decline in tariffs and increase in international trade? Now, however, political economists are pressed to answer another question: why have developed Western countries, after so much success in liberalizing trade, begun to revert to protectionism? We saw some of the initial efforts from scholars like Grossman and Helpman, working to reconcile their previous groundbreaking work with the new reality of populist protectionism. More work still needs to be done, however, both to clarify the ongoing contradictions and uncertainties in the field, and to keep up with a continually evolving international trade environment.

Bibliography

A 501tax-exempt, The Center for Responsive Politics, charitable organization 1300 L. St NW, Suite 200 Washington, and DC 20005 telelphone857-0044 info. 2022. “Did Money Win?” OpenSecrets. 2022. https://www.opensecrets.org/elections-overview/winning-vs-spending.

Ardelean, Adina, and Carolyn L. Evans. “Electoral Systems and Protectionism: An Industry-Level Analysis.” The Canadian Journal of Economics 46, no. 2 (2013): 725–764.

Baccini, Leonardo, and Johannes Urpelainen. “International Institutions and Domestic Politics: Can Preferential Trading Agreements Help Leaders Promote Economic Reform?” The Journal of Politics 76, no. 1 (2014): 195–214.

Bailey, Michael A., Judith Goldstein, and Barry R. Weingast. “The Institutional Roots of American Trade Policy: Politics, Coalitions, and International Trade.” World Politics 49, no. 3 (1997): 309–338.

Betz, Timm, and Amy Pond. “The Absence of Consumer Interests in Trade Policy.” The Journal of Politics 81, no. 2 (2019): 585–600.

Bohara, Alok K., Alejandro Islas Camargo, Therese Grijalva, and Kishore Gawande. “Fundamental Dimensions of U.S. Trade Policy.” Journal of International Economics 65, no. 1 (2005): 93–125.

Cortez, Florian Kiesow. “Domestic Institutions and the Political Economy of International Agreements: A Survey and Hypotheses.” In The Political Economy of International Agreements, 9–35. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 2021.

Ehrlich, Sean D. “Access to Protection: Domestic Institutions and Trade Policy in Democracies.” International Organization 61, no. 3 (2007): 571–605.

Ehrlich, Sean D., and Eddie Hearn. “Does Compensating the Losers Increase Support for Trade? An Experimental Test of the Embedded Liberalism Thesis.” Foreign Policy Analysis 10, no. 2 (2014): 149–164.

Fajgelbaum, Pablo D, Pinelopi K Goldberg, Patrick J Kennedy, and Amit K Khandelwal. “The Return to Protectionism.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135, no. 1 (2020): 1–55.

Gawande, Kishore, Pablo Pinto, and Santiago Pinto. “Heterogeneous Districts, Interests, and Trade Policy.” Working paper (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond) 23, no. 12 (2023): 1–44.

Goldstein, Judith, and Robert Gulotty. “America and Trade Liberalization: The Limits of Institutional Reform.” International Organization 68, no. 2 (2014): 263–295.

Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. “Protection for Sale.” The American Economic Review 84, no. 4 (1994): 833–850.

Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. “A Protectionist Bias in Majoritarian Politics.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 4 (2005): 1239–1282.

Grossman, Gene M, and Elhanan Helpman. “Identity Politics and Trade Policy.” The Review of Economic Studies 88, no. 3 (2021): 1101–1126.

Hankla, Charles R. “Party Strength and International Trade: A Cross-National Analysis.” Comparative Political Studies 39, no. 9 (2006): 1133–1156.

Hicks, Raymond, Helen V. Milner, and Dustin Tingley. “Trade Policy, Economic Interests, and Party Politics in a Developing Country: The Political Economy of CAFTA-DR.” International Studies Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2014): 106–117.

Hiscox, Michael J. “The Magic Bullet? The RTAA, Institutional Reform, and Trade Liberalization.” International Organization 53, no. 4 (1999): 669–698.

Karacaovali, Baybars. “PRODUCTIVITY MATTERS FOR TRADE POLICY: THEORY AND EVIDENCE: Productivity Matters for Trade Policy.” International Economic Review (Philadelphia) 52, no. 1 (2011): 33–62.

Kim, In Song. “Political Cleavages within Industry: Firm-Level Lobbying for Trade Liberalization.” The American Political Science Review 111, no. 1 (2017): 1–20.

Kim, Sung Eun, and Krzysztof J. Pelc. “The Politics of Trade Adjustment Versus Trade Protection.” Comparative Political Studies 54, no. 13 (2021): 2354–2381.

Limão, Nuno, and Patricia Tovar. “Policy Choice: Theory and Evidence from Commitment via International Trade Agreements.” Journal of International Economics 85, no. 2 (2011): 186–205.

Magee, Stephen P., Leslie Young, and William A. Brock. Black Hole tariffs and endogenous policy theory: Political Economy in General Equilibrium. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1989.

Maggi, Giovanni, and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare. “A Political-Economy Theory of Trade Agreements.” The American Economic Review 97, no. 4 (2007): 1374–1406.

Maggi, Giovanni, Monika Mrázová, and J. Peter Neary. “Choked by Red Tape? The Political Economy of Wasteful Trade Barriers.” International Economic Review (Philadelphia) 63, no. 1 (2022): 161–188.

McGillivray, Fiona. “Party Discipline as a Determinant of the Endogenous Formation of Tariffs.” American Journal of Political Science 41, no. 2 (1997): 584–607.

Nelson, Douglas. “Domestic Political Preconditions of US Trade Policy: Liberal Structure and Protectionist Dynamics.” Journal of Public Policy 9, no. 1 (1989): 83–108.

Nielson, Daniel L. “Supplying Trade Reform: Political Institutions and Liberalization in Middle-Income Presidential Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 47, no. 3 (2003): 470–491.

Oatley, Thomas. “International Institutions and Domestic Legislatures: GATT, RTAA, and the Stability of Tariffs in Congress.” International Organization, September 1999, 1–41. https://doi.org/https://www.academia.edu/76374419/International_Institutions_and_Domestic_Legislatures_GATT_RTAA_and_the_Stability_of_Tariffs_in_Congress.

O’Reilly, Robert Francis. “Domestic Institutions and International Trade Policy.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2003.

Pincus, J. J. “Pressure Groups and the Pattern of Tariffs.” Journal of Political Economy 83, no. 4 (1975): 757–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1830398.

Pinheiro, Flavio. n.d. “Political Representation and Protectionism: Assessing How Electoral Institutions Affect Tariff Levels.” Dissertation, Department of International Relations University of São Paulo. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://sdpscp.fflch.usp.br/sites/sdpscp.fflch.usp.br/files/inline-files/2-84-1-PB.pdf.

Plouffe, Michael. “Firm Heterogeneity and Trade-Policy Stances Evidence from a Survey of Japanese Producers.” Business and Politics 19, no. 1 (2017): 1–40.

Putnam, Robert D. “Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization 42, no. 3 (1988): 427–460.

Rickard, Stephanie J. “Electoral Systems and Trade.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Political Economy of International Trade. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Ritchie, Melinda N., and Hye Young You. “Trump and Trade: Protectionist Politics and Redistributive Policy.” The Journal of Politics 83, no. 2 (2021): 800–805.

Roelfsema, Hein. 2003. “Political Institutions and Trade Protection.” Proposal, Utrecht School of Economics, Utrchet University. https://www.diw.de/documents/dokumentenarchiv/17/41572/Paper-135.pdf.

Saha, Amrita. “Trade Policy & Lobbying Effectiveness: Theory and Evidence for India.” European Journal of Political Economy 56 (2019): 165–192.

Soeng, Reth, and Ludo Cuyvers. “Domestic Institutions and Export Performance: Evidence for Cambodia.” The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 27, no. 4 (2018): 389–408.

Staiger, Robert W., and Alan O. Sykes. “International Trade, National Treatment, and Domestic Regulation.” The Journal of Legal Studies 40, no. 1 (2011): 149–203.

van Aaken, Anne, and Jürgen Kurtz. “Beyond Rational Choice: International Trade Law and the Behavioral Political Economy of Protectionism.” Journal of International Economic Law 22, no. 4 (2019): 601–628.

Yu, Miaojie. “Trade Protectionism and Electoral Outcome.” The Cato Journal 29, no. 3 (2009): 523–557.

Zissimos, Ben. “A Theory of Trade Policy under Dictatorship and Democratization.” Journal of International Economics 109 (2017): 85–101.