2 Trade: International Institutions

Learning Objectives

Upon competing this chapter and activities, learners should be able to

- Comprehend the functions of trade as a building block for International Political Economy.

- Gain greater insight into the functions of GATT and WTO in reference to the International Political Economy.

- Recognize the importance of institutional design facilitating policy goals, especially internationally.

- Utilize critical thinking to determine the significance of WTO and its efforts today on the international stage.

Introduction

As Chapter One mentioned, countries turned inward and increased trade barriers after World War I, especially in the late 1920s as financial crisis heightened the fears of spiraling domestic markets. Countries also tried but were unable to return to the classical gold standard that stabilized the international monetary system during Pax Britannica. Why did countries rethink their relationships with the global economy? One reason was the absence of international commitments to maintain openness, and by the end of World War II, efforts were underway to create international institutions that would help countries reduce trade barriers and keep their economies open to foreign products.

The U.S. would assume the leadership role of this endeavor working alongside with much of the Western World. In part this was due to its economy, which was undamaged from the war. American leaders were determined to create a foundation for postwar economic growth that would restore international trade and increase commercial incentives to maintain peace. Overall, they hoped that international institutions would further the goal of furthering the global economy by helping countries to commit to opening their economies to imports in exchange for reciprocal liberalization in other countries.

But first, it’s important for us to revisit World War 2 and reckon with its destruction, which left states’ economies utterly shattered. As countries began to scramble to rebuild their societies, they sought a new avenue in restoring their prominence. This led to the Bretton Woods Conference (1944), an attempt to create an international institution looking to revitalize Europe’s economies and set the standards for international trade. Although the original plans of the Bretton Woods Conference regarding trade did not come to fruition, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) would become the foundation for restoring international trade. Arising as a set of temporary guidelines with only 23 members, GATT would expand, adding more member countries and finding new challenges as time passed on. Numerous rounds of negotiations occurred to clarify rules and to make GATT adaptable to an ever-changing global economic environment. The Uruguay Round (1986-93) resulted in the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the primary international organization for international trade. The WTO has tried to further set the rules of global trade, while it also implemented new rules to ensure smooth processes of trade in the world. Notably, the Doha Round (2002-2015) was another attempt to revitalize the rules and international trading system, but was not met with resounding success, and in general, the WTO’s ability to increase international trade is now widely questioned.

The rest of the chapter examines all three of these experimental institutions in search of a trade liberalization model. We dive into the questionable aspects of each that led to their stagnation as well as the more admiral aspects that originally gave them legitimacy. It culminates to the WTO’s current tenuous position in advancing global trade and what will need to happen to see a tipping of the scales once again toward trade liberalization.

The International Trade Organization (ITO)

At the close of 1944, as the war was coming to an end both the allied and axis nations were faced with incalculable damage. The obvious portion of this was done to the infrastructure of the respective nations, but even the health side took a substantial blow. Estimates proclaim that the standard of living was cut by 25 years for the winning side, with even lower numbers being shared by their opponents, reducing the standard of living. To restore international economic stability 44 of those allied states would meet at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. There all parties would share ideas on how to supplant the ill-effects endowed to their countries leading to the notorious name of the Bretton Woods Conference.

Three institutions would stem from delegations at the conference: the International Banks for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the International Trade Organization (ITO) each with their own purpose. The IBRD aimed to provide credit to countries that needed to rebuild their economies. The IMF focused instead on the international monetary system with the goal of stabilizing currencies. Finally, the ITO would be responsible for reducing trade tariffs and incentivizing economic cooperation among the world’s states.

Although the IMF and the IBRD were established in 1945 and 1946 respectively, the ITO was delayed mainly due to domestic concerns in the United States, which received disproportionate voting power in the other two Bretton Woods institutions. The US Congress was displeased with the idea of having just one vote in the ITO, and so, consequently, the organization was never brought to a vote. Even more, protectionist ideals of American businesses proved hard to please, further striking the bid for the ITO charter. Without American support, the ITO never came into existence. However, all was not lost as GATT partially filled the ITO void.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

Despite its failures, the ITO was an unprecedented venture to broaden the accessibility of goods to the global market. Its demise was preceded by the formation of the General Agreement Trade and Tariffs which took on the basic framework of the ITO charter. As countries were vying on how to reduce tariffs, a group of 15 members that stemmed from the original ITO charter met to tackle first the issue of custom tariffs. Long-held protectionist measures were specifically targeted so that goods could have broader access. In the end of deliberations, that number would grow to be 23 countries all poised to lead the charge for trade liberalization. GATT’s main messaging was of course to limit trade tariffs to supply goods at a more affordable price, but the institution was similarly concerned in dismantling the unilateral influence that trade discussions were bound by. Two key features of the institution would allow that idea to stand: reciprocity and Most Favored Nation (MFN).

Reciprocity meant that countries simultaneously reduced trade barriers and was used as a tool in limiting the influence of externalities imposed on trade talks. Previously, countries could impose whatever restrictions they deemed beneficial to themselves in terms of trade. The introduction of reciprocal trade liberalization tied together the trade policies of member countries. Countries might hesitate to open their borders to foreign trade unilaterally, but would be more willing to do so when they knew that their exporters would gain from openness gained in other countries. By invoking reciprocity, GATT encouraged concessions from both parties to edge closer to moderations in negotiations (Bagwell and Staiger 1999). It is worth noting that this provision was not exactly exalted by the poorer nations of the institution. They lacked adequate bargaining power to convene with any country in providing goods that could be leveraged as a concession, leaving them with less room to advocate for trade measures.

The provision of nondiscrimination, or more formally known as MFN, would further reverse any tipping of the scale action during trade discussions by granting those poorer states with more insurance. By its definition, countries are not allowed to give preferential treatment to another member that is not applied to the organization. So, if a country were to enact a lowering of trade barriers to one of its trading partners, it would be expected to carry those same concessions with all trading partners.

Through reciprocity and MFN, GATT helped to increase trade substantially among GATT members in its first years. Such economic successes eventually led to more growth for member states’ economies, and over time, other countries began to join GATT, as they became convinced of the benefits of international trade. As negotiations succeeded on tariffs, members eventually turned towards other, more complex trade barriers, such as antidumping duties, that became primary methods of trade protection as the use of tariffs waned. By 1993, 128 countries grew to be a part of GATT. Once again economic issues, global trends, and GATT’s increasing size would lead to another round of trade negotiations.

Multilateral Trade Bargaining

Much of the progression throughout GATT’s history took place during rounds of bargaining among member states. For instance, The Kennedy Round would focus on anti-dumping laws as well as development, while the Tokyo Round would home in on decreasing industrial tariffs. But perhaps the most successful round held under GATT was the Uruguay Round. Lasting from 1986 to 1993, the Uruguay Round of negotiations had two specific objectives; to bring overlooked areas of commerce to the GATT system and incorporate areas like agricultural sectors that had previously been ignored by the trade liberalization agenda. The Uruguay Round incorporated many aspects of the trade policy, including services and intellectual property, which were not previously part of the regime (Barton, et al., 2008 p.93). It was one of the most successful rounds by making agreements more applicable to all parties by implementing all elements of the state.

On the agricultural side the intended goal was to both lower trade tariffs for all member states as well as target other liberalization measures. Starting first with the tariff reductions we would see a concentrated effort on the part of both developed and developing nations in reducing the tax imposed on goods. The bulk of this action would be taken over by the bigger economies, but the move saw large reductions in tariffs relating to agriculture products and even spices. Subsidies were also a topic of concern during these discussions. The idea behind the position assumed that limiting the number of subsidies in both domestic and international markets would free up space for imports. It was previously held that countries who engaged in dishing out subsidies would only embolden their own economies. This runs counter with the intent of liberalization so it would only make sense to see a reduction in subsidies so that countries should specialize in their most effective industries while importing from the least efficient sectors. We also saw a shift in international trade in terms of services. As the sector began to boom members felt a need to include it within the trade talks, so it too could be properly moderated in relation to other spheres. Its components included service dealing with hotels, consulting services, and financial services such as Citicorp (Fieleke 1995).

Another pre-GATT trade agreement was the intellectual property front. Much like the service sector, this industry would gain more prominence over the years, making its inclusion in this round an obligation. As expressed by some members” Governments have long endeavored to protect the ownership rights of inventors, writers, and other producers of intellectual property, but no multilateral system of principles and rules has existed to discipline international trade in counterfeit items.” From this conclusion, we would see a stress in offering proper protection for intellectual property through copyright claims, trademarks, and patents. These moves provided much needed affirmations on the safety of intellectual assets through mechanisms such as the MFN principle (treatment must be applied equally) and the transparency principle.

Yet, as always, there remained criticism of how the round played out. Some postulate that the deliberations were too one sided in favor of bigger nation states. It is implied that the smaller states had little purchasing power in some of the measures pertaining to agriculture tariff reductions as well as how sophisticated new entries such as intellectual property worked, which hindered their ability to defend some of its provisions. Many smaller organizations felt sore about the absence of human needs and the overhaul between the more powerful states in dealing with industrial tariffs as well.

Despite this, the Uruguay Round was still clearly the most crucial step taken to further trade liberalization since the 1940s. As a result, more tariffs were lowered in the world, and more nations became official members of the GATT organization. The Uruguay Development Round (or The Uruguay Round) was perhaps one of the largest sets of trade negotiations introduced in modern history and took “seven and a half years,” lasting from 1986 to 1993. (WTO n.d.). It was not only the most encompassing in terms of the issues it targeted (the round focused on issues like “services liberalization…intellectual property rights, and sanitary and phytosanitary standards…”), but was directly responsible for the creation of the WTO in 1995.It showed how effective trade deliberations could be when all sides are willing to make concessions to bolster the market in totality.

The World Trade Organization (WTO)

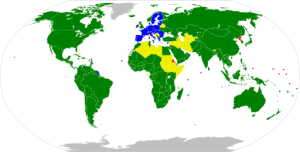

The World Trade Organization only came into existence after succeeding GATT in 1995 during the Uruguay Rounds. The goal of the WTO is to ensure that global trade happens smoothly, freely, and predictably. The WTO currently has 166 members, all of which have ratified the rules of the organization in their individual countries (WTO website, 1 September 2024). The WTO tends to support the removal of trade barriers, which allows international trade to follow its natural course without hindrances such as tariffs, quotas, or other restrictions.

Environmentalists have long had concerns that the WTO privileged trade would be prioritized over health and environmental concerns, and it is important to understand that this organization has systems in place in order “for the protection of human, animal or plant life and health, and natural resources” (WTO 2024), which was enforced in the case brought by India, Malaysia, Pakistan and Thailand against the US, like adopting trade-related measures that ensure the flow of it to be smooth and predictably to raise people’s living standards. The appellate and panel reports were adopted in 1998. The WTO has six objectives: (1) to create and enforce rules for international trade, (2) to provide a forum for negotiating and monitoring trade liberalization,(3) to create a space to resolve trade disputes, (4) to increase the transparency of countries decision-making process, (5) to cooperate with other major international economics management globally, and (6) to aid developing countries so they may benefit fully from the global trade system (Anderson 2021). By encompassing all goods, services, intellectual property, and investment property, the WTO pursues its objectives more comprehensively than GATT – which focuses exclusively on goods. Through these objectives, the WTO attempts to ensure stability in global trade.

The WTO prevents countries from discriminating between their trading partners through principles such as MFN and National Treatment. The MFN treatment helps ensure that there is no discrimination as well that each country treats the 140 fellow-members equally, then the national treatment coincides with this treatment by allowing that all the locally and imported goods are treated with the same treatment as one’s own nationals — which ensures that no matter who or what is being taking into consideration when putting a tax on it there is an equilibrium all throughout the process.

The Most Favored Nation treatment requires countries to provide identical treatment to all other members of the WTO. For Example, if the United States were to apply a 2.6 percent tariff on an import from the European Union, then the United States must apply a roughly 2.5 percent tariff on imports from every other WTO member country. One reason that the WTO may not have allowed their members to have free trade agreements would be due to it showing unfair treatment to the other members of the WTO. However, free trade agreements can be if it is within its region like the USMCA for North America and the EEA for Europe are necessary because it would aid economic integration within their regional areas. Additionally, developing countries can gain special access to markets, and countries can choose to raise barriers against products, and in some instances services, which are unfairly traded from specific countries (WTO 2022). This means that nations may have their Most Favored Nations Status removed that ensures a country’s promise to fairly treat another country no matter if it is local or foreign. Currently, the United States has suspended 30 total countries from their Most Favored Nation Status (Kenton 2021). For example, as of April 7, 2022, the United States Congress voted to strip Russia of its Most Favored Nation Status following the invasion of Ukraine, which signified that they were going to be held “accountable for this unjustified and unprovoked war that has already isolated Russia in the world” (Partington 2022).

The WTO uses national treatment as another nondiscrimination policy. The national treatment requires WTO members to treat foreign products no differently than the domestic product after it has cleared customs. Under national treatment, countries may still apply tariffs to foreign products that would otherwise not be applied to the domestic product with the caveat that the foreign product must be treated equally after it passes through customs.

Dispute Settlement Mechanism

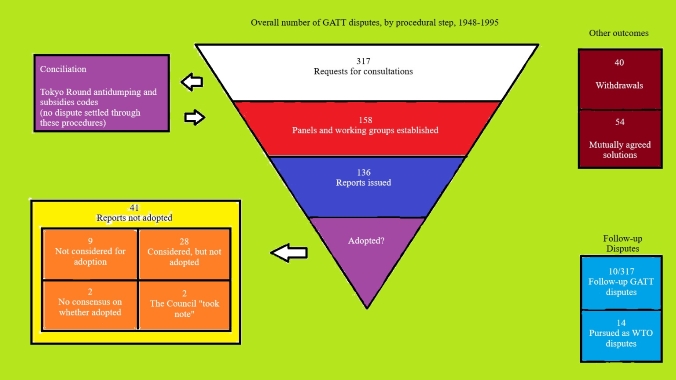

Disputes may arise in the WTO if a member country adopts a trade policy or takes an action that a fellow-WTO member believes to be breaking a WTO rule or obligation. The Dispute Settlement Mechanism was introduced during the Uruguay Round agreement after GATT dispute settlement measures lacked fixed timetables which created a court backlog. The Uruguay Round introduced a structured process with clearly defined stages, and greater consideration for the length of time the case should take (WTO 2022). For example, should a case run its full course with an appeal, the case should take up to 15 months, which is important to note that these cases do frequently go on longer than is statutorily allowed.

The WTO dispute settlement process begins with a request for informal consultation between parties. If the consultation failed to resolve the dispute, the party may request the appointment of an investigating panel, which comprises three members. After receiving oral and written submissions from both parties, the panel issues a report along with the panel’s recommendation. Should a party wish, they may seek an appellate review of the panel’s report and recommendation. The appellate body may uphold, modify, or reverse the panel’s report and recommendation. However, most cases do not reach the panel phase of the dispute settlement, meaning that disputes are often settled without legal proceedings. Even then, the WTO rules can influence states to abide by their commitments by removing illegal trade barriers.

The Doha Round

Despite Uruguay’s Round’s successes, it left several problems unresolved. Despite all that was achieved by Uruguay’s Round, these trade negotiations ultimately failed to do one thing: provide a fair distribution of real and tangible benefits for developing countries. Uruguay’s Round failed to provide developing countries with better access to rich countries’ markets for the products they tended to produce, and it was the failure of the Uruguay Round that served as the impetus for the WTO to establish the new Doha Development Round during its fourth Ministerial Conference in Doha, Qatar, in November 2001. Additionally, it was meant to include the needs of developing as well as less-developed WTO member countries. The many issues that centered around the Doha Round: (1) Reduced tariffs on export of developing countries, (2) facilitating freer trade for agriculture and agricultural goods, and (3) revising rules surrounding trade in services. Unfortunately, the failure of Doha Round bargaining is a lost opportunity for the WTO. Though it was meant to boost the economic growth of developing countries, its continuous disagreements between China, India, Brazil, and other large economies with the rest of the developing world eventually led to downfall of the Doha Round.

Unlike the Uruguay Round, the Doha Round was never able to achieve the same number of successes. The Doha Round ultimately failed to achieve many of the issues on its initial agenda during its odd fourteen-year period. The subject of agricultural tariff reduction and more free access for developing countries in the realm of agricultural trade was an incredibly touchy subject regarding international trade. The importance of agriculture has been a big concern since no matter if you’re the consumer or producer of these products the impact of the trade market affects everyone around them; additionally, the WTO concluded in 1995 that the agreement in agriculture that “initiated reductions in subsidies and trade barriers to make markets fairer and more competitive” (WTO 2024). Historically, agriculture is one area of international trade that the most developed countries came to be stricter on as agriculture is the foundation that helps cities and civilizations grow as well that without farming the world that is present would not have been possible. Producers in developed countries are protected by high tariffs and domestic government subsidies which, among other measures, have effectively barred developing countries from achieving any meaningful trade gains on this front.

So, the Doha Round’s objectives became apparent: to fully get rid of “all forms of export subsidies, and substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic support,” (Verbiest et al. 2002, pg.4). Though the Doha Round did make some headway in this area, as we will soon discuss, there is some disagreement over the purported effectiveness of some of the solutions proposed in this round. Firstly, the participating member countries of the Doha Round all officially agreed to eventually abolish export subsidizing the year 2013, a decision that was fastened in the year 2005 by the Hong Kong Ministerial. Despite this consensus however, this agreement’s “effectiveness might be somewhat less than suggested,” given that export subsidies can essentially be “replaced by the same subsidy provided as a domestic subsidy,” (Lester 2016, pg.1). What is more would be that in the more recent Nairobi Ministerial conference, domestic agricultural subsidies were not dealt with and “remain high and are proliferating,” (Lester 2016, pg.1). While some progressions penning agricultural trade for the benefit of developing countries has been made, the issue remains largely unresolved due to the developed countries’ refusal to budge on the issue of domestic subsidies and trade-distorting protections as well that some of the less developed countries are holding off in their support due to the system overwhelmingly distorting against them and having no agreement or treaty that will grant them growth as a country.

Another major area of concern for the Doha Round was the issue of increased Trade Liberalization and Trade Facilitation across the board, specifically for developing countries. Though the Doha Round, as mentioned above, failed to properly address some of the significant issues on its agenda, the development round did manage to produce some noteworthy, albeit modest, progress in the realm of Trade Facilitation with the ratification of the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA). The TFA was ratified in December 2013 at the Bali Ministerial Conference and is the “first new WTO multilateral agreement” since the actual creation of the WTO at the end of the Uruguay Round (Eliason 2015, pg. 643). The purpose of the TFA, and the Trade Facilitation in general, is to ensure the smooth, frictionless entry of goods into a country with as menial cost and barriers to entry as possible. The TFA itself could reduce the cost of cross-border trading by $1 trillion through its capacity to “improve transparency …[reduce] institutional limitations, and [improve] access to information,” (Eliason 2015, pg. 644-645). About efforts in promoting the removal of trade restrictions to facilitate the free exchange of goods between nations, the Doha Round produced the second iteration of the Information Technology Agreement. The (second) Information Technology Agreement is a trade agreement amongst 53 WTO member countries at the 2015 Nairobi Ministerial Conference aimed at significantly lowering tariffs on information technology products (Lester 2016, pg. 2).

The WTO Today

The Doha Round of negotiations encountered numerous obstacles in attempting to achieve many of the issues on its agenda, either due to external factors or internal, structural faults latent within the WTO. Developing nations did not receive any substantial benefits from these negotiations in the way of increased market access for agricultural products or increased support for implementation of the objectives outlined in the TRIPS agreement. More importantly, the outcomes (or lack thereof) of the Doha Round may have broader implications for the WTO, questioning it as an efficacious institution in its attempts to promote frictionless international trade.

Even more detrimental to the WTO’s mission has been the paralysis of the dispute settlement’s Appellate Body, which is no longer functioning. Problems began in 2011 when the Obama administration prevented the reappointment of American Jennifer Hillman, who was already serving as a member, and then other members. The Trump administration continued to block all appointments and reappointments to the AB, and in 2019, it lost the ability to make quorum of three members. As a result, the WTO appeals process has now completely lost any ability to hear WTO disputes (see Schneider-Petsinger 2020).

Conclusion

In discussions about international trade, both the General Agreements on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) have played important roles. The postwar economic and political environmental set the stage for the need for a rules-based system for international trade and the need for an institution to facilitate the flow of trade. Taken together, both GATT and the WTO have produced some of the most all-encompassing, internationally recognized, and politically important trade agreements in modern history whose outcomes have wide-reaching economic and political implications. From its inception in 1947 to 1995, GATT has undergone eight complete rounds of trade negotiations among increasing numbers of members with each round ultimately serving the goal of reducing international trade barriers and promoting a more open and more transparent system for global trade among countries. Among GATT’s many achievements in promoting international trade, the eighth and final round of trade negotiations – known as the Uruguay Round – is perhaps the institution’s crowning achievement. As discussed previously, the Uruguay Round was one of the most exhaustive sets of negotiations and trade agreements (ranging from agriculture to sanitary standards to intellectual property) ever constructed in modern history and, ultimately, epitomized the GATT’s mission statement; in which this was the round of negotiations that created GATT’s successor: The WTO.

The WTO’s purpose was, like GATT, to reduce global trade barriers and facilitate freer trade between nations. The WTO now includes three times as many members as GATT and takes into consideration the interest of many more nations. But while the WTO might be GATT’s successor, has it truly succeeded where GATT has otherwise stumbled? The outcomes, or lack thereof, of the latest round of trade negotiations under the WTO (the Doha Round) point to a more pessimistic answer. While the Doha Round was set to address issues that were important to developing nations, issues that were not properly addressed in the Uruguay Round, the negotiations met various internal and external roadblock and failed to achieve anything meaningful. As mentioned before, issues on market access for agricultural goods from developing nations, reductions in trade-distorting domestic, support for agricultural goods in developed nations, and other such problems persisted to some extent, so even after many negotiations over an extended period. So where does this leave the WTO? Is the Doha Round a unique case? Can the WTO move on and continue to push towards its primary objective in the way its predecessor had done? Or are the difficulties encountered in the Doha Round reflective of a larger, internal problem of the WTO? Should developing nations, whose interest have either been neglected, denied, or pushed back, seek out alternative means (i.e. regional trade agreements) of reducing trade barriers and realizing their economic pursuits? Or is the WTO simply no longer relevant in today’s international stage? While these questions may not have an immediate answer, it is important to consider as the WTO pushes into a future of economic uncertainty and international instability. For the goals of the WTO to be realized, the institution itself, as well as its successes and failures, must constantly be reevaluated.

Worked Cited

Bagwell, Kyle, and Robert W. Staiger. 1999. “An Economic Theory of GATT.” American Economic Review 89 (1): 215–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.1.215.

Barton, J., Goldstein, J., Josling, T. and Steinberg, R. 1998. The Evolution of the Trade Regime: Politics, Law, and Economics of the GATT and the WTO. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Eliason, A. (2015). The Trade Facilitation Agreement: A New Hope for The World Trade Organization. World Trade Review, 14 (4): 643-670.

Fieleke, Norman S. 1995. “The Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations: An Overview.” New England Economic Review. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. May–June, 3–14.

Keating, W. 2015. The Doha Round and Globalization: A Failure of World Economic Development? Thesis, The City University of New York, New York. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=hc_sas_etds

Lester, S. 2016. “Is the Doha Round Over? The WTO’s Negotiating Agenda for 2016 and Beyond.” CATO Institute Free Trade Bulletin No. 64. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2784917

Partington, R. 2022, March 11. “G7 nations strip Russia of ‘most favoured nation’ status.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/11/g7-nations-drawing-up-plans-impose-heavy-tariffs-russia-ukraine

Schneider-Petsinger, M. 2020. “Reforming the World Trade Organization.” Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/09/reforming-world-trade-organization/04-dispute-settlement-crisis

Solovy, E. M. 2022, December 14. “Policy brief: The TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines, and its potential expansion: Assessing the impact on Global IP protection and Public Health.” Center for Intellectual Property x Innovation Policy. https://cip2.gmu.edu/2022/12/14/policy-brief-the-trips-waiver-for-covid-19-vaccines-and-its-potential-expansion-assessing-the-impact-on-global-ip-protection-and-public-health/

Verbiest, J-P., Liang, J., and Sumulong, L. (2002). “The Doha Round: A Development Perspective.” ERD Policy Brief Series. Asian Development Bank.

World Trade Organization. 2000. “WTO | Understanding the WTO – the Uruguay Round.” Wto.org. 2000. Retrieved from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact5_e.htm.

World Trade Organization. n.d. “Understanding the WTO – Trade and Environment.” Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/envt_rules_intro_e.htm

World Trade Organization. n.d. “Understanding the WTO – Uruguay’s Ground Agreement: Agreement on Agriculture.” Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/14-ag_01_e.htm

World Trade Organization. n.d. “Understanding the WTO – The Agreements: Intellectual Property – protection and enforcement.” Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/agrm7_e.htm