4 Trade: Domestic Institutions and Policymaking

Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter and the activities involved, learners should be able to:

- Identify how different regime types affect international policies and how it also affects domestic political institutions.

- Understand how the Access Point Theory of Trade influences trade policy decision-making.

- Understand how the electoral frameworks and interest groups contribute to trade policymaking decision.

- Be able to explain the dynamics between domestics and international institutions in trade policymaking decision.

Introduction

A country’s trade policy can be seen as a result of aggregated trade preferences of its domestic institutions. Domestic institutions typically refer to the officially established channels through which policy is formed. Most countries have economic institutions, political institutions, and interest groups. By analyzing the frameworks and priorities of each of these categories we can gain an understanding of how trade policy is proposed and implemented.

This chapter will discuss how economic and political regime type can impact the ability of the domestic institutions to contribute to trade policy. Regime type also influences the way a country negotiates trade policies with other countries. Though the world is filled with various economic and political regime types, an offer of trade relations can bring almost any country to the negotiating table. Historically, trade policy has also been used as a tool of foreign policy. Domestic economic and political institutions have rallied around trade policies that serve as deterrent or punishment for political regimes that have offended global norms.

This chapter will also discuss the role of interest groups in the formation of trade policy. An interest group is a group of people that form around a common policy goal and seek to advocate for this policy. The term interest groups often conjures an image of wealthy business representatives pressuring elected representatives to vote in their favor. While this is one version, interest groups range from nonprofit advocacy groups seeking civil rights improvements to political action committees (PACS) funding the campaign for candidates that align with their values.

This chapter will look at how domestic institutions interact with international institutions. When it comes to trade, domestic institutions focus on the control of importing and exporting. A domestic political institution may wish to appeal to constituents by promising a restriction on imports, thus protecting the constituents livelihoods. A domestic economic institution may wish to reduce volatile and complex supply chains. Accomplishing these goals would be easier said than done as domestic institutions must content with the norms of international institutions that oversee international trade. Finally, this chapter will examine three historical cases that illustrate how regime type can influence domestic institutions, and how those domestic institutions influence trade policy. These cases will specifically analyze the effect of interest groups being able to advocate for protectionist policies in a time of global economic downturn.

The Access Point Theory of Trade

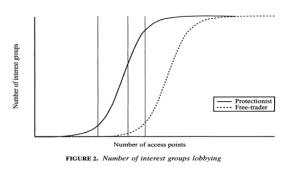

One of the most influential dynamics in the making of trade policy is the relationship between interest groups and policymakers. A major factor in determining outcomes in trade policy is the domestic institutional framework in which these groups operate. The number of access points refers to the opportunities interest groups have to engage with the policymaking process. Access points are one of the most important institutional characteristics in determining trade policy, with greater access leading to the implementation of a more protectionist trade policy (Ehrlich, 2007). In addition, the collective action capabilities of groups are an important determinant of whether institutional opportunities can be leveraged to their advantage. Well funded interest groups are able to use these funds to organize and donate, creating more access points with each donation. For example, an interest group may fund a candidate with common trade policy preferences knowing that the election of that candidate will advance their policy goals. In other cases, the interest group may donate to a candidate in exchange for the politician answering the phone when the interest group calls.

Many interest groups working with and creating access points with many politicians compounds the impact that interest groups have on policymaking. This access point theory argues that aggregate protectionist lobbying power outweighs that of the free trade lobby. Combined with the ability to impact policymaking through numerous avenues, more protectionism on the whole (Ehrlich, 2007). Researchers also tested this theory by investigating the impacts of political parties and system type on these trade policy dynamics. When there are a greater number of political parties involved in the system, researchers observed a positive relationship with the tariff amounts that were instituted—both in the short and long term of the policy horizon (Ehrlich, 2007). In addition, presidential systems tend to be associated with much lower tariffs, exhibiting a nearly ten percent decrease compared to countries governed by other types of domestic political institutions (Ehrlich, 2007). This is likely due to the fact that presidents typically deal with macro, state-wide economic concerns, and are also typically less beholden to individual interest groups than other policymaking actors such as individual legislators.

How Regime Types Affect Trade

Since the era of mercantilism, political economists and researchers have engaged in debates relative to the state’s role in development and its international trade. In the post-World War era, but most especially after the Cold War, market economies proliferation was no longer limited to liberal democratic states. Therefore, this phenomenon draws the researchers’ attention to the link between regime type and a nation-state’s international trade policies.

The diversity of political systems (heterogeneity of regime type) in different countries, can have a significant impact on international trade. It is noteworthy to point out that the relationship between regime type and trade is complex and it has been explored by many scholars in the field of political economy (Simmons and Elkins, 2004). It is not accurate to say that autocracy encourages trade liberalization, or that democracy is against trade liberalization. In fact, the relationship between regime type and trade policy is more complex than a simple binary of autocracy versus democracy. While some scholars have argued that autocratic regimes may be more likely to pursue trade liberalization because they do not face the same pressures from domestic interest groups as democratic regimes, others have suggested that authoritarian regimes may also be more likely to engage in protectionism and limit trade.

Similarly, while democracies are often associated with free trade, this is not always the case. Democracies may face pressures from domestic interest groups or political opposition that can lead to protectionist policies or limits on trade. For example, in the United States, a democratic country, protectionist policies such as tariffs on steel and aluminum were implemented by the Trump administration in 2018, were seen as contrary to the principles of free trade. On the other hand, China, an authoritarian country, has pursued a policy of economic liberalization and trade openness since the 1990s, despite its autocratic regime.

One key argument relative to regime type is that democracies are more likely to engage in free trade because democratic regimes are more accountable to their citizens which makes it more responsive to public demands for economic growth and access to international markets. On the other hand, authoritarian regimes may prioritize political stability over economic liberalization, leading to protectionist policies and barriers to trade. Other scholars have challenged this view, arguing that regime type alone does not necessarily determine a country’s trade policies. Rather, factors such as domestic interest groups, the distribution of economic power, and historical legacies may also play a role in shaping a country’s trade policy (Simmons and Elkins, 2004).

For example, in their study of trade openness in China and India, Lee and Swenson (2018) found that although China is an authoritarian regime and India is a democracy, both countries pursued similar policies of economic liberalization and trade openness in the 1990s and 2000s. The authors suggest that this was due to a convergence of economic interests and ideas among elites in both countries, rather than a reflection of their regime types. Another study by Simmons and Elkins (2004) examined the impact of regime type on the adoption of international legal agreements. They found that democracies were more likely to ratify and implement international trade agreements, but the effect of regime type was mediated by other factors such as economic openness and the presence of international organizations.

Relative to regime types and their effects on trade, it is noteworthy to mention that states (governments) began to reduce barriers to trade in the mid-nineteenth century, whereby Britain was the first to repeal its “Corn Laws” in the 1840s, and opened its market to imported grains (Oatley, 2019 p.16). Additionally, in 1860, Britain and France eliminated significant trade barriers between them by executing the Cobden-Chevalier Treaty. This treaty subsequently triggered a wave of trade negotiations and immediately established a network of bilateral treaties which substantially reduced trade barriers in Europe. On the other hand, The United States refused to embrace the nineteenth-century trade liberalization, it remained staunchly protectionist up until the 1930s (Oatley, 2019).

Overall, the relationship between regime type and trade is complex and may be influenced by a range of factors beyond just the type of political system. The specific factors that shape a country’s trade policy are likely to be shaped by a variety of factors, including domestic political pressures, economic interests, and global geopolitical trends (Frieden, 1991). Further research in this area could continue to explore these nuances and identify the specific mechanism through which regime type may impact a country’s trade policies.

Electoral Frameworks and Trade

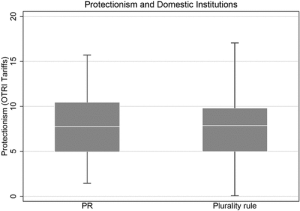

Additional research has touched on the relationship between electoral system type and interest group access to trade policymaking as well as the importance of the interplay between international trade negotiations and domestic political institutions. The differences between plurality rule and proportional representation systems have been a particular focus when determining the causes of where the trade policy lies on the continuum between free trade and protectionism. The plurality rule is more conducive to allowing very particular interest groups to exert substantial influence on trade policy, whereas the characteristics of proportional representation systems tend to make policymakers more responsive to a much broader set of less-organized interested parties (Betz, 2017). The smaller, single-member districts which typically occur in plurality electoral systems make individual legislators more beholden to local interests which tend to favor protectionist policies which work in their self-interests (Betz, 2017). In addition, the plurality rule tends to exhibit a wider overall range in the degree of protectionist trade policies that are instituted in a particular state. Figure 1 shows applied tariffs, Overall Trade Restrictiveness Index (Kee, Nicita, and Olarreaga 2009), for proportional representation and plurality rule. The figure displays the mean (as the bright horizontal line within boxes), upper and lower quartile (as the limits of the box), and upper and lower adjacent values (as the whiskers) for each group (Betz, 2017).

The Dynamics Between Domestic and International Institutions in Policymaking

The relationship between states and the coordination of international trade policy is a complex one that highlights the importance of domestic political institutions. Because international negotiations on trade are dependent upon reciprocal actions between states, exporters constitute an important interest group whose influence depends largely on the opportunity for involvement within the system of domestic political institutions in which they operate (Betz, 2017). These sorts of factors are important aspects of the strategies that are employed by international organizations. International trade institutions are likely to have more success at instituting their policy aims when member states have domestic political institutions that allow for more interest group influence in the policymaking system (Betz, 2017).

Lobbying and Policymaking

Political parties and interest groups occupy important, albeit awkward, places in the American political system. Neither parties nor interest groups are mentioned anywhere in the Constitution, and many of the founders distrusted “factions” of all kinds. Nonetheless, political parties and interest groups have emerged as the most important intermediaries between individuals and decision-makers in the federal and state governments (Lowry 2021). At the intersection between the political and the economic spheres lies the lobbying industry. Trillions of dollars of public policy intervention, government procurement, and budgetary items are constantly, thoroughly, scrutinized, advocated, or opposed by representatives of special interests (Bertrand et al., 2011).

Lobbyists’ connections to politicians are a significant determinant of what legislative issues they work on. Specifically, a lobby that works on trade policies and international relations, is systematically more likely to be connected (through campaign contributions) to legislators whose committee assignments include trade and relations. A large part of the theoretical literature on interest groups has painted the lobbying process as one of information transmission. Informed interest groups send cheap or costly signals to uninformed politicians. However, these stylized models of lobbying do not account for the presence of the lobbying industry as an intermediary. The role that the lobbyists themselves play in the lobbying process and how they use their specific skills and assets are some, if not all particularly valuable to the interest groups which hire them. According to one view, lobbyists are the experts who provide information to legislators and help guide their decision-making process. Their expertise might be particularly valuable when one considers that neither legislators nor the interest groups which hire lobbyists may have the technical background or the time to delve into the detailed implications of all the pieces of legislation that are under consideration (Bertrand et al., 2011).

There is deep skepticism about what exactly lobbyists do. There are two main views widely discussed by scholars and in the media. The first view considers lobbyists as issue experts who can contribute valuable information to the law- and rule-making process; the second considers them more as sources of access to lawmakers, because of their personal ties and knowledge of those lawmakers. While both lobbyists’ expertise and their connections might be at play in the lobbying process, the value analysis suggests that connections are the scarcer resource and therefore the one that commands the highest price (Bertrand et al., 2011).

Domestic Politics of Trade Policy

In 1989, Magee, Brock, and Young created a model of trade policy in which politicians chose trade policy strategically to gain campaign financing. They called this the endogenous tariff theory: in this theory, there are two presumptions that help define the endogenous approach to political economy. The first presumption is that final policy choices are systematically related to the economic effects of the chosen policy. The second presumption is that the relevant economic effects can be derived from standard, neoclassical, and or microeconomic models of the economy. (Nelson 1988). As a result of this process, tariffs arose – in other words, they finally had an explanation for trade protection.

Domestic politics matters for trade policy is now a well-established trope in both economics and political science. International trade and international relations more generally are not determined by a sole national executive, acting autonomously and isolated from the pressures of domestic political interests when choosing tariff levels, health and safety rules, and regulations, or other elements of trade policy. Instead, trade policy, like any other domain of public policy, is determined by the interplay of domestic economic interests, domestic political institutions, and the information that is available to all involved players. International trade theory offers a natural starting point for the political economy of protection. The classic Heckscher-Ohlin model of trade in which a country’s factor endowments play a crucial role in determining the pattern of trade also allows clear predictions of the effect of trade on the relative incomes of factor owners. (Leeds 1999)

While identifying individual and firm preferences is the first step towards a complete model of trade policy, the next one is to specify how they influence policymaking. What can now be regarded as an endogenous process – lobby formation – was black-boxed until the seminal work by Grossman and Helpman (1994). The main idea behind Grossman and Helpman’s (1994) theory of endogenous protection is best described by the paper’s title: “Protection for Sale.” It argues that special interest groups can use campaign contributions to incentivize politicians to adopt favorable trade policies. There is a contribution schedule as the announcement by a lobby of the number of campaign contributions it is willing to make in exchange for a given policy. The equilibrium is then defined as “a set of contribution schedules such that each lobby’s schedule maximizes the aggregate utility of the lobby’s members, taking as given the schedules of other lobby groups.” It is industries’ relative importing or exporting nature that will affect their decision to deviate from free trade. Grossman and Helpman (1994) take the existence of organized groups as a given, but Mitra (1999) endogenizes the lobby formation process.

Historical Cases

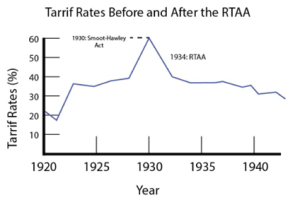

Domestic political institutions play a big role in trade policies so, in order to understand why countries decide to enact certain policies, we must discuss how their intuitions decide policies, historical trends, and similarities across regions. The first country we will discuss in the United States. The U.S. has not always had the same system to decide trade policies. Prior to 1934, trade policy was made and decided in both Houses of Congress: the House of Representatives and the Senate. Having the legislative branch make trade policies allowed interest groups to have greater access to the policy-making process and often ensured policies that would help protect industries were enacted. During this period of U.S. history, trade policy tended to be more protectionist which refers to having policies that protect domestic industries over foreign ones. Trade policies were protectionist because industries had more access points to the policy-making process which meant they had many opportunities to lobby for policies that would protect their industries. As expected, tariff rates remained high during this period with the average tariff rate of the United States being set at 60% in 1930 by the Smoot-Hawley Act.

The trend of protectionism and high tariff rates ended in 1934 when the Reciprocal Trade Agreement Act (RTAA) was passed. The RTAA moved the power to set tariffs from the legislative branch to the executive. This also tied tariff reduction to foreign concessions. Now, why would Congress agree to give up the power they had to set tariff rates? There are a few reasons that could have led to the RTAA being passed. One reason is that it could have been done to help reduce the workload of Congress. Another reason could have been that Congress had decided that they were not the best branch to make trade policy. The third possible explanation is that Democrats wanted lower tariffs even when Republicans were in majority so to reduce the partisan issues, Congress decided to let the executive branch deal with trade policies. When Congress had the power to set tariff rates, the trend tended to be that when Democrats took, they would decide to lower tariffs while Republicans did the opposite. The RTAA had two primary rule changes for trade policymaking. The first was that it mandated reciprocal tariff reductions as opposed to the unilateral reductions like there was previously. The second change was that it required the ratification of trade agreements by simple majority votes instead of the supermajority. Since the RTAA was passed,protectionist groups like the ones that had greatly influenced trade policymaking, lost their influence and have not been as successful since.

The changes the RTAA brought are important because it shows how domestic political institutions can greatly influence policy making. By shifting trade policy-making powers to the executive, the RTAA not only made free trade a possibility in the U.S. but also eventually changed the optimal policy choices of elected officials. Now, we should discuss how trade policy-making of other countries is influenced by their domestic political institutions. As we have seen, legislators have been able to be influenced by protectionist lobbying but this is not the case in all countries. Unlike in the United States, where legislators were susceptible to protectionist demands due to their independence from their parties, in countries like Canada and Australia, party discipline is high. This means that legislators often stick to the policies favored by their party so they are less susceptible to protectionist lobbying that could lead to high tariff rates as the United States had prior to 1934.

Other countries, such as Chile following the Great Depression, began adopting a trade protectionist model instead. Using the Import Substitution Industrialization model, local producers were at an advantage as their products were prioritized in the market in comparison to exports priced with a higher tariff. As foreign competition charged consumers high prices due to tariffs, domestic manufacturers were able to significantly raise their own prices to gain a higher profit. This led to Chilean citizens paying astronomical prices for items that could’ve been lower in a non-protectionist economy.

As Chile attempted to be a self-supporting economy, manufacturers were forced to produce goods where they lack the skill of properly manufacturing in comparison to foreign competition, leading to lower quality products at high prices. Products of lower quality also tended to malfunction at a quicker pace compared to the imported goods from places that manufacture higher quality of a said product. For example, consumers had to pay up to 52% more for a pair of pants than if they were able to with an open international market (Edwards, 2009). These high prices made it difficult for the average working-class person to afford many goods.

Importers struggled with selling in Chile as they were heavily taxed for their products. However, they were subjected to make 10,000% deposit prior to selling in the Central Bank of Chile while said goods were held in customs (Edwards, 2009). The deposit combined with the country’s ever-growing inflation rate of 30% per year also contributed to the high prices placed on imported goods.

Exporters also have difficulty making a profit selling abroad as the Chilean government strengthens the worth of the Escudo. This made the export profit worth less in local currency than with foreign currency. The effect of the overvaluation of the Escudo was equal to an export tax ranging from 24-32% of the value of the exported goods (Edwards, 2009).

It is a common belief that democratic regimes often produce policies encouraging trade liberalization and that autocrats will encourage trade protectionism. Nevertheless, not everyone fits this stereotype and decides to do the opposite. The following country we will discuss is Spain under the Franco dictatorship, where an autocracy encourages trade liberalization.

The dictatorship of Francisco Franco in Spain saw both trade protectionism and trade liberalization. When Franco stepped into power in 1939, Franco decided he wanted the economy of the nation to be separate from the rest of the world. To do this, he created many policies against the free trade market and alienated Spain from the global economy. However, this led to an economic downfall for the country as inflation rates multiplied, there was not much foreign investment coming in, and the emergence of black markets.

As Franco realized that the country would continue to suffer with its current economic policies, in the 1950s, he began implementing changes that would allow Spain to reenter the free market. The first major step taken was the Pact of Madrid, a military and economic agreement between Spain and the United States signed in 1953. In this pact, Spain allowed the United States to use its military bases in exchange for economic aid. During the first ten years of the pact, the United States sent different kinds of economic aid that totaled around $1.5 billion (Solsten, Meditz, Library of Congress, 1990).

Following the Pact of Madrid, Franco spent the rest of the 1950s trying to liberalize Spain leading to the implementation of the Liberalization and Stabilization Plan (PSL) in 1959. This Plan focused on three main areas: reducing inflation, liberalizing domestic markets, and liberalizing foreign economic relations (Prados de la Escosura, Rosés, J.R., & Sanz-Villarroya, 2012). Economists figured out that the high inflation came from a lack of monetary discipline, leading them to create policies that controlled spending by the public and decreased the discount rate in the Bank of Spain. Most of the domestic market was inaccessible to the global economy, so the PSL began to suppress regulations regarding international trade and update policies to ease administrative procedures to allow trade to be more accessible. Along with liberalizing the market, the final area the PSL focused on is the liberalization of foreign economic relations. Strict tariffs and quotas were relaxed to complete this, and Spain increased its presence globally.

A prime example would be at the end of 1958 when Spain’s peseta currency became integrated with the Bretton Woods system and convertible with the major European currencies. Before 1958, Spain had a robust black market for foreign currencies, as official exchange rates were outrageous. However, with the integration into the Bretton Woods system, official exchange rates became reasonable, dissolving the black market due to a lack of demand. Taking part in the Bretton Woods system also relaxed Spain’s then-restrictions regarding foreign direct investment and international trade, leading to 80% of total trade liberalization and the near disappearance of quotas by 1973 (Prados de la Escosura, Rosés, J.R., & Sanz-Villarroya, 2012).

In the graph below, we see exports and imports as a percentage of Spain’s GDP over time (Prados de la Escosura, Rosés, J.R., & Sanz-Villarroya, 2012). We see the graph reach an all-time low in 1942, three years after Franco took over. As years went by, we saw a slow increase until right before 1954, when the Pact of Madrid was signed. Afterwards, the levels of exports and imports began to reach the same levels prior to the Spanish Civil War. After 1959 and the implementation of the Liberalization and Stabilization Plan, we see that imports and exports continue to historically grow.

Figure 4 OPENNESS, 1850-2000 (EXPORTS AND IMPORTS AS % OF GDP)

Sources: Prados de la Escosura (Reference Prados de la Escosura 2003).

The change from protectionism to trade liberalization during the Franco dictatorship was significant to history as it became a case of institutional heterogeneity. After a failed attempt to keep Spain productive outside the global market, Franco decided it would be better for the country to open up to trade again. The economic growth following the implementation of the Liberalization and Stabilization Plan in 1959 up until the 1970s became known as the “Spanish Miracle.”

Conclusion

The interactions between domestic political institutions and trade policy remain a dynamic domain of understanding, both in the literature as well as in the real-world policymaking process. Theory suggests that countries with democratic political institutions are more likely to have more collaboration and input from different actors in the trade policymaking process than in autocratic states which place decision- making authority in the hands of a small number of individuals. In addition, differences have been observed between states with strong democratic institutions. Research has found that differences in electoral processes can affect policy outcomes, with plurality systems tending to exhibit more trade protectionism than proportional systems. The presence of strong domestic political institutions is also a major determinant of whether or not international trade institutions are successful in fostering reciprocity between nations and healthier trading relationships. At the intersection between the political and the economic spheres lies the lobbying industry. The role that the lobbyists themselves play in the lobbying process and how they use their specific skills and assets are some, if not all particularly valuable to the interest groups which hire them. Nonetheless, political parties and interest groups have emerged as the most important intermediaries between individuals and decision-makers in the federal and state governments (Lowry 2021). Trade policy, like any other domain of public policy, is determined by the interplay of domestic economic interests, domestic political institutions, and the information that is available to all involved players. As we have seen, this applies in many countries including the United States where interest groups played a large part in the process of making trade policies, especially before 1934. Lobbying led to strict protectionist policies that would not have been as extreme if it were not for the interest groups pushing for the policies. Having multiple players involved in the policymaking process is a characteristic of many democratic nations. This shows how the access point theory applies to American policymaking. When there were many different access points for influence before the RTAA, Congress implemented protectionist policies. After the RTAA, the number of access points decreased and trade liberalization began. A contradiction to this theory, however, is seen in the protectionism of countries such as Chile following the Great Depression. As the global economy fell into a depression, Chile began relying mainly on itself to produce the products that used to be imported following the Import Substitution Industrialization model. Throughout history we see many examples of autocracies promoting trade protectionism and democracies promoting trade liberalization to the point where we associate the trade policy with the type of institution. However, there are instances where a government goes out of the norm and displays an act of institutional heterogeneity. The Liberalization and Stabilization Plan of 1959 used in Spain under the Franco dictatorship is a prime example of institutional heterogeneity as we see an autocracy switch from promoting trade protectionism to encouraging trade liberalization.

Opportunities for Future Research

Continued investigation into the inner workings of the lobbying apparatus could provide a better understanding of how these powerful interests devise strategies for seeking the implementation of advantageous trade policy. On the empirical side, integration of the access point theory and the concept of veto players (political actors who must provide their approval in order to allow changes in policy) may provide additional insight into the actions necessary to succeed within particular institutional frameworks (Ehrlich, 2007) (Tsebelis, 1995). In addition, research into both the causes of individual attitudes toward trade, as well as the dynamics of collective action in policymaking may further this line of inquiry (Alkin et al., 2015).

Works Cited

Aklin, Michael, Eric Arias, Emine Deniz, and B. Peter Rosendorff. “Domestic politics of trade policy.” Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences, Wiley Online Library (2015).

Bertrand, Marianne, Matilde Bombardini, and Francesco Trebbi. 2014. “Is It Whom You Know or What You Know? An Empirical Assessment of the Lobbying Process.” American Economic Review, 104 (12): 3885-3920. DOI: 10.1257/aer.104.12.3885

Betz, Timm. (2017). Trading Interests: Domestic Institutions, International Negotiations, and the Politics of Trade. The Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1237–1252.

https://doi.org/10.1086/692476

Dijkstra, A. G. (2000). Trade Liberalization and Industrial Development in Latin America. World Development, 28(9), 1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00040-1

Edwards, Sebastian. “Protectionism and Latin America’s Historical Economic Decline.” Journal of policy modeling 31, no. 4 (2009): 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2009.05.011

Ehrlich, Sean D. (2007). Access to Protection: Domestic Institutions and Trade Policy in Democracies. International Organization, 61(3), 571–605.http://www.jstor.org/stable/4498158

Ehrlich, S. D. (2008). The Tariff and the Lobbyist: Political Institutions, Interest Group Politics, and U.S. Trade Policy. International Studies Quarterly, 52(2), 427–445. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29734242

Feinberg, R. (2008). Policymaking in Latin America: How Politics Shapes Policies/Civil Society and Social Movements: Building Sustainable Democracies in Latin America. Foreign Affairs, 87(5), 177.

Fernandes, Ana Margarida, Klenow, P., Meleshchuk, S., Pierola, M., and Rodriguez-Clare, A. The Intensive Margin in Trade. (2018). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8625, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3273672

Frieden, J. A. (1991). Invested interests: The politics of national economic policies in a world of global finance. International Organization, 45(4), 425-451.

Hillman, A. L., & Ursprung, H. W. (1988). Domestic Politics, Foreign Interests, and International Trade Policy. The American Economic Review, 78(4), 729–745. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1811171

Kim, In Song, Londregan, J., & Ratkovic, M. (2019). The Effects of Political Institutions on the Extensive and Intensive Margins of Trade. International Organization, 73(4), 755–792. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818319000237

Lee, J. W., & Swenson, G. (2018). Heterogeneous autocrats: Trade policy in China and India.

Leeds, B. A. (1999). Domestic political institutions, credible commitments, and international cooperation. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 979. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991814

Lowry, Robert. “Political Parties and Interest Groups Syllabus.” University of Texas at Dallas, 2021. https://personal.utdallas.edu/~rcl062000/Syll4326.pdf.

Nelson, D. (1988). Endogenous tariff theory: A critical survey. American Journal of Political Science, 32(3), 796. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111247

Oatley, T. H., & EBSCOhost. (2019). International political economy (Sixth edition.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Prados de la Escosura, Rosés, J. R., & Sanz-Villarroya, I. (2012). Economic reforms and growth in Franco’s Spain. Revista de Historia Económica, 30(1), 45–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0212610911000152

Simmons, B. A., & Elkins, Z. (2004). The globalization of liberalization: Policy diffusion in the international political economy. American Political Science Review, 98(1), 171-189.

Solsten, Eric, Sandra W Meditz, and Library Of Congress. Federal Research Division. Spain: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress: For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O, 1990. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/90006127/.

Tsebelis, G. (1995). Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Multicameralism, and Multipartyism. British Journal of Political Science, 25(3),289-325.

- Need sources and captions for all figures