9 Finance: Bretton Woods Monetary System

Learning Objectives

- Become familiar with the Mundell-Fleming economic theory and how it affects international political economy

- Understand the context for the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944

- Learn about the reasons behind the failure of the Bretton Woods system

At the turn of the twentieth century, gold played a key role in anchoring the value of many countries’ currencies. In what has come to be known as the classical gold standard, nearly all countries held the value of their currencies in connection to a fixed quantity of gold. This was the basis of the international monetary system which became dominant in the 1870s and lasted until World War I. Between World Wars I and II, disorder and volatility marked the financial realm. The interwar period (1918-1939) was characterized by harsh economic outcomes of the great depression and financial competitiveness which resulted in countries wanting to keep their currency at a low value compared to other currencies, benefitting exports and reducing imports. The devaluations of currency during the interwar period created instability internationally. This called for revision which resulted in a conference of 44 allied nations to conjure an improved international monetary system that is tailored to international needs and boosts unity amongst states.

Pictured above are U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin during the Yalta Conference held in 1945, which discussed post-war options for peace.

The Bretton Woods Conference

The Bretton Woods Conference was held in 1944 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. The goal of the conference was to establish a new international monetary system to promote greater international trade through creating a standardized exchange rate as well as assisting less developed countries and those which were ravaged by the events of World War II, which was in its closing stages at the time of this meeting. A conference of 44 allied nations gathered to establish a new international monetary system:, which used the experience of The Great Depression and The Gold Standard to create a new international monetary system with a focus on Post-War reconstruction.

The two largest groups present at these talks each had differing schools of thought on how this new system would function. One group was led by British representative John Maynard Keynes while the other was led by American representative Harry Dexter White. Both sides of this debate had the common goal of attempting to promote greater international trade by doing away with the rampant protectionism which was particularly unsatisfactory during the years preceding the Second World War. Keynes and White agreed that the unregulated capital flow which had been occurring between nations in the past was a destabilizing influence that promoted predatory trade practices and had to be solved, they also believed that it was vital for there to be some type of system for assisting countries which were running payment deficits so as to shore up the potential weak points in the international market.

After much deliberation, White’s school of thought gained the popular vote, and consequently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) received much less funding than Keynes had anticipated. The United Kingdom along with every other nation which signed onto the agreement had their currencies pegged to the value of the Dollar while the dollar was attached to gold. Even so, the IMF continues to operate and has even grown its reserves a great deal since its inception. The ridged exchange rate between currencies which White tried to introduce, has fallen by the wayside over the years in favor of much more flexible rates of exchange. From this process, it can be said that although the American ideal may have won during the initial debate, over time, the Keynes position seems to have proved itself to be the more sustainable of the two systems.

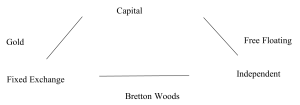

The difference between the new Bretton Woods System and the previous Gold Standard can be illustrated by the Mundell-Fleming trilemma which argues that there is a certain extent of mutual exclusivity between the so-called “Impossible Trinity.”

The Mundell-Fleming trilemma argues that any country can simultaneously achieve at most two of the following three economic goals:

1. Exchange Rate Stability, achieved by maintaining fixed exchange rates between the national currencies of different states;

2. Autonomous Monetary Policy, or the ability of states to control their monetary policy;

3. Capital Mobility, or the free movement of capital across borders.

The classical gold standard paired exchange rate stability with capital mobility, meaning that states were required to forfeit control over their domestic monetary policies. In the time of the Great Depression, when people were more concerned about rampant unemployment rates than less immediate matters such as currency stability, states were forced to abandon the old system in order to meet the needs of their people.

Those present at the Bretton Woods Conference knew that the new system would have to be tailored to the needs of the present time. Thus, while the Bretton Woods System incorporated fixed exchange rates as its predecessor did, it was willing to sacrifice capital mobility so that states could retain autonomy over their domestic monetary policies.

Creation of the International Monetary Fund

The IMF was created in 1944 in the Bretton Woods meetings. Some parties such as Keynes wished for it to have a good amount of influence, but White and the Americans did not. It had some action in its first year, however, it fell to the wayside during most of the time under the Bretton Woods system as the Americans’ plan had won out. It was more of a show of collective action and commitment than an enforcing agency. It would find new influence in the time that followed the Bretton Woods system, so we will mostly ignore it in this chapter.

Evaluating the Bretton Woods System

The Bretton Woods system that White argued for solidified the style of both domestic monetary policy autonomy and international exchange rate stability that countries around the world would follow for some time. Countries were required to peg their currencies to the dollar at $35 dollars an ounce. They also could change the par values to correct any minor imbalances in their balance of payments. These two aspects of the triangle offered both a flexibility to make some changes while having a rigid backbone to keep things steady. One large cause of the success was the low number of countries in the initial agreement allowed for much easier collective action within the ideas in the system and the similarity of the countries made it simpler for them to follow the system collectively. The other large aspect that success can be attributed to is the closed nature of domestic economies and that actual change was made by these countries within. The system helped to facilitate economic growth and stability in many countries during the post-World War II period. One example of a country using the Bretton Woods system for success during the time period of its operation is West Germany. The Bretton Woods system also allowed West Germany to benefit from a stable international financial system to support its post-war economic recovery. The country experienced significant economic growth during the 1950s and 1960s, becoming one of the world’s leading economies by the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971.

The US held so much power in this system not only because it was White’s idea, but also because during the postwar period they had a very large share of the global economy. This allowed them to support the system and provide a backbone. Winning the war led to a group of allied countries that would eventually work with this system and hold the dollar. In these ways the US was the global “hegemon” that oversaw this global system and majorly assisted in it working.

Bretton Woods over Time

The Dollar Shortage Period

During the time from 1947-1958 the world experienced something known as the Dollar Shortage Period. There was a large demand for dollars as implied in the name from countries and a limited supply. Trade imbalances were being experienced in the US and it was worsening over time. The US began taking on dollar deficits for stability and assisting other countries so the want for gold would be reduced. An example is the Marshall plan that supported much of Europe in their postwar economic recovery.

Dollar Glut Period

This was a time from 1958-1971 where the world had an overflow of dollars. One of the causes for this was an increase in speculation on gold which in response the US sold some reserve gold and took measures to discourage this practice. Another cause was from direct government action that discouraged individual Americans and banks/firms from buying foreign securities and sought to reduce the outflow of US dollars. The increased amount of dollars did help bring economic growth for a while, however it would slow down eventually.

Case Study: France

Now let’s apply this knowledge and take a look at what France was doing during this period of time in history. It is widely argued that France and its monetary policy had a very large influence on the decline and the overall collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system. French contention with the Bretton Woods system began very early in the system’s inception and continued up until the final nail in its coffin. In this case study, we will examine the French history, relationships, and responses to Bretton Woods policies and the system itself.

France, like many other Western and allied nations, sent delegates to the original Bretton Woods conference to present ideas and plans about the future infrastructure of the international monetary system. However, unlike the US who was economically spared from World War II, France was economically and industrially decimated. So even though historically France was seen as a great power in international affairs, their input in the new monetary system was mostly sidelined in favor of American and British plans. This lack of influence extended into the early years of the Bretton Woods system (Bordo et al, 1994).

One of the first real conflicts between France and The Bretton Woods System came in 1948 when France decided to devalue its currency to take advantage of the weak currency situation throughout Western Europe, as well as creating a multiple exchange rate system. These monetary actions went against the agreements laid out in Bretton Woods, so in response, France was denied funds from the International Monetary Fund for 4 years until 1952. (Bordo et al, 1994).

The French economy began to expand greatly with considerable help from the American Marshall plan. Also, in response to withheld funds, France also singularly pegged their currency at 350 francs to the dollar. However, after a few years, economic growth in France slowed and inflation began to climb. They also faced an ever-increasing budget deficit as well as balance of payment issues. The French had no real solution for this until the newly elected president, Charles de Gaulle, took power. Under his rule, France reduced expenditures and raised taxes to address the budget deficit. But again, contrary to the goals of Bretton Woods, they devalued the franc to 493.7 on the dollar (Bordo et al, 1994).

As well as altering monetary and fiscal policies, French economists began to envision a future of the monetary system which shifted away from the hegemony of the US dollar. One economist of note, Jacques Rueff, was very influential in the De Gaulle government, pushing France to enact policies that conflicted with The Bretton Woods System. Rueff was very skeptical of the domination of the US dollar as a reserve currency and the staggering deficit the US was taking in its balance of payments. To avoid issues with these balance of payments issues, Rueff proposed to move away from the asymmetric Bretton Woods system to a symmetric system in which countries would not be able to constantly increase their deficits. In order to move closer to a system like this, Rueff thought that the US should pay all of its outstanding dollar debts to central banks in gold. Rueff, in effect, wanted to go back to a new gold standard (Bordo et al, 1994).

As the reserve countries of the US (as to a smaller extent the UK) continued to increase their balance of payments deficits, French calls for establishing a balance of payments equilibrium began to increase in intensity. But while some economists such as Rueff wanted to leave Bretton Woods all together, the official French position was to resolve the balance of payments issues while preserving Bretton Woods. At a 1963 meeting of IMF governors, the French delegation pointed to a few critiques of the system, even if they wanted to maintain it: one is that the reserve nations needed to address their balance of payment deficits, two that it was unfair that reserve nations could easily finance deficits while other countries could not (Bordo et al, 1994).

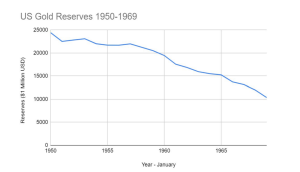

Beginning in 1965, the French were buying up large quantities of gold with US dollars. D’Estaing, the French Minister of Finance, justified the buildup of mass gold reserves to accelerate a crisis in the international monetary system which would force the reserve nations to consider reforms. The same year, de Gaulle suggested that a return to the gold standard was an appropriate move, since at this time, the total gold reserves held by member nations equaled that of the United States. As late as 1966, many French officials continued suggesting that the international monetary system ought to return to the gold standard (Bordo et al, 1994).

As demands for global liquidity grew though this time period, French economists proposed that a new global reserve unit be created: the Special Holdings Unit. This reserve currency would be directly linked to the value of gold. In the French plan, nations would receive an amount of the currency in proportion to the amount of gold reserves they had. This plan was adamantly opposed fiercely by the US because it would eliminate their exclusive ability to create more of the reserve currency, hindering their economic hegemony. In an attempt to appease the French out of their desire for the gold standard, the US suggested creating a new reserve unit that was not linked to gold. However, this backfired when the French decided to take a hard line in negotiations and dropped support for the reserve unit in favor of a complete return to the gold standard (Bordo et al, 1994).

By 1967, US held gold reserves were reaching very low levels. This prompted the US to ask the international community to limit the conversion of dollars into American held gold. The action further fielded French objections to the issue of US balance of payment deficits, France decided to suspend its contribution of gold to the international gold pool to keep prices at $35 an ounce. Because France refused to contribute, the US had to use more of its gold supply instead. Once news of this was leaked to the public, it triggered a gold buying spree. Since gold prices were intended to be kept at $35 an ounce, the US was forced to flood the market with their reserves. In light of this, members of the international monetary system agreed to reduce the importance of gold in the system. To do this, countries proposed that only currently held gold would have value in the international monetary system. No newly mined gold would be able to be part of it. This proposal was adamantly opposed by France, with de Gaulle saying that they would not try to maintain the strength of the dollar unless a return to the gold standard was achieved. As well as this opposition, the French proposed for the first time that the price of gold should be increased. Despite French opposition, the new policy was ratified by member countries (Bordo et al, 1994).

France makes for an interesting case because the very system of Bretton Woods that helped postwar weakened countries grow, especially France, would allow them to later become stable enough and point out the flaws in that same system. Another takeaway is the French insistence for a return to a gold standard fueled speculation on the price of gold, putting enormous stress on the reserves of the US. With US reserves dwindling and the market price of gold rising, America and its close allies were willing to forgo the gold-based system all together and put them on the road to abolishing Bretton Woods altogether.

End of the System

The cracks in the system were beginning to show and economist Robert Triffin would sound the alarm. Triffin had reported in the 1960s that there was trouble brewing in concern to the Bretton Woods system. The issues that began to develop are as follows: the dollar would have to be liquid for all countries since this was the currency the world was using, meaning that countries would have to have a reserve of U.S dollars. At the beginning of Bretton Woods this was not an issue as there was not a large amount of U.S dollars around the world. However, this became an issue in the 1950s and 60s since the dollar started to become more readily available. On top of this the United States was starting to run deficits in balance of payments meaning that the United States could no longer back up the amount of dollars in circulation in gold. In the Bretton Woods system, the dollar was pegged to gold at $35 per ounce.

In a sense the dollar was meant to be “as good as gold” meaning that countries that held these U.S dollars could claim the amount of dollars’ worth in gold during the Bretton Woods system. Triffin argued that having a large amount of U.S dollars around the world would increase inflation in the home country. Meaning, that while it was needed for the United States to spread the money around, this could have a negative impact on the United States and creditors would start wondering if the USD was actually representative of the gold held in the U.S treasury. Therefore, whoever was the leader of the world currency under the Bretton Woods system would have to decide between doing what was needed for the world economy or for its home country.

With the problems beginning to mount and people beginning to lose faith in the value of the dollar, efforts were made to try and fix the system. To combat this, additional “lines of credit” were put in place on top of the existing systems to allow for greater global capital liquidity. Credit swaps and Special drawing rights were such lines of credit.

Special Drawing Rights is a concept that is similar to what the French would propose but would not be directly linked to gold. It is something that the International Monetary fund wanted to create in 1970 for a reserve asset for members. It was unique by not being tied down to one currency but a handful of popular and influential ones. This is something that was invented to combat the issues that the Triffin Dilemma caused but was never fully utilized by countries.

The formation of a Gold pool allowed for an official sale of gold bullion. There was also a private market that was decoupled from the official market that allowed the price of gold to fluctuate. The implementation of both public and private pools only led to a gold run.

These temporary fixes would do little since the biggest problem by far was the abuse of the dollar by the United States itself. Because of the huge bills that would continue to pile up for social programs, and lavish spending on foreign policy that included the growing quagmire that was the Vietnam Conflict, Speculators began to see the dollar as a bigger and bigger target.

The Adjustment Problem and the Nixon Shock

There were no options that would please everyone. Germany would not accept inflation while the United States would not accept a high unemployment rate, all the while the U.S had lost the economic strangle hold it had on the world. Many of the major players on both sides of the second world war had risen from its ashes and had globally competitive economies that could be used as political leverage. This included the Soviet Union which was bent on challenging the U.S. in any and every way possible. Both domestic and foreign affairs made it impossible for the major economies to agree on a solution on Balance of Payments.

During the mid-to-late 1960s several major currencies would experience currency devaluations starting with the Pound sterling in 1964. The importance of the pound would cause not only speculation attacks on the Deutschmark and the Franc but put tremendous pressure on the dollar as well. Both the direct speculative pressure as well as the ripple effects of other currency devaluation forced the U.S to eventually abandon the gold standard system.

The tension between short- and long-term economic goals identified in the Triffin paradox meant that confidence in the US dollar was on the decline. Many countries adopted France’s way of thinking and decided they would rather hold onto gold itself rather than the US dollars that it backed. The demand for gold increased significantly as everyone tried to trade in US dollars that had been accumulating overseas. The United States’ gold reserves, which had comprised two-thirds of the world’s gold just 30 years earlier, were nearing depletion (see Figure 3). There simply was not enough gold in the world for it all to be traded at a rate of $35 an ounce.

Stress on the Bretton Woods System continued to build until finally, on August 15, 1971, President Nixon announced that the United States would be implementing major changes to its monetary policy. These changes are collectively known as the Nixon Shock. By far the most significant of these changes was the temporary suspension of convertibility of the US dollar to gold. The Bretton Woods System was designed to provide exchange rate stability and monetary policy autonomy, but in a way, it also depended on these two things to function. The “closing of the gold window,” as it was called, effectively knocked one leg out from underneath the table and rendered the whole system inoperative. Another change brought forth by Nixon’s announcement was the implementation of a 10% tax on goods imported into the United States. This measure was meant to make American products more competitive and help mitigate high unemployment rates.

In his address to the nation, Nixon declared that “the United States has always been and will continue to be a forward-looking and trustworthy trading partner, and… we will press for the necessary reforms to set up an urgently needed new international monetary system.” With this statement, Nixon admitted that the Bretton Woods System was unsustainable, at least in its current form. Indeed, some scholars believe these reforms marked the end of the system. Others would argue that it did not truly end until attempts to revive it had failed.

The Smithsonian Agreement and The End

The Smithsonian Agreement was a final push to try and restore confidence in the Bretton Woods System, reset it, and restart it. At the meeting it was decided to revalue the dollar and several major currencies as well in relation to the dollar. The meeting also intended to have regular additional talks like a doctor’s visit to continually reevaluate how the system was doing. This, however, was futile as no one was really persuaded by the effort. At last the Bretton Woods system was abandoned once and for all for a free floating system. By1973, most large economies had moved towards the free floating “system” of today.

|

Date |

Event |

Dollar to gold exchange rate |

|

July 1-22, 1944 |

Bretton Woods Conference |

$35 per ounce of gold |

|

Aug. 15, 1971 |

Nixon Shock |

USD not convertible to gold |

|

Dec. 17-18, 1971 |

Smithsonian Agreement, 8.5% devaluation of the USD in relation to gold |

$38 per ounce of gold |

|

Feb. 12, 1973 |

Additional 10% devaluation of the USD in relation to gold |

$42 per ounce of gold |

Conclusion

In this chapter we have discussed the key points of Bretton Woods Monetary System: its conception as an idea, its history, the key players in the system, its failings, and how it was viewed by differing powers. Bretton Woods was a system that was implemented after World War II to provide currency stability and greater capital flow. At first, the system held but the changing needs of those at the top and bottom as well as the effects of consistent abuse would play out as the United States was unable to keep up with the amount of USD needed around the globe. Some argue that the United States held too much power within the system as other currencies were chained to the ebb and flow of not only dollars but policy shifts of the United States as well. In modern times, similar situations play out as governments try to balance social policy and the health of their currencies and national economies, but without the safety net that even today, the U.S. somewhat still enjoys.

Essentially, the Bretton Woods System was too inflexible for an economy that required a large amount of liquidity from the U.S while the USD was pegged to gold. It required the United States to put the international economy before its national economy for continuing to distribute USD could cause inflation for the home country. As history shows, this is something that the United States was unwilling to adapt to. Nixon temporarily paused Bretton Woods after his Aug 15, 1971 speech. However, the system as it was could not be salvaged. Whether Bretton Woods was effective or not is debatable. It provided enough stability in those crucial years for the world economy to recover from the devastation of war but at the same time it was not prepared for the emerging globalization that it helped create. The world has moved beyond the Bretton Woods system. The new era of floating exchange allows countries more flexibility but the amount of deficits countries are running are already boiling over and causing economic uncertainty.

The Mundell Fleming Trilemma says that states cannot have it all: capital mobility, fixed exchange rates, and independent monetary policy. Under Bretton Woods countries had fixed exchange rates and independent monetary policy. Today, countries typically choose to not have fixed exchange rates and opt for capital mobility and independent monetary policies. However, the decision of which of the two out the trilemma to choose rests independently on individual countries. When looking at differing perspectives, not everyone agreed on how the Bretton Woods system should function. While the U.S and U.K, to a lesser degree, were the dominating voices in the Bretton Woods agreement, France did not agree with the system. France preferred the tangibility of a global gold standard and questioned why the U.S and the U.K could easily run a deficit while other countries could not. A country might be in a weakened state for a time but if governed even moderately well, it will seek advancement to either make a name for itself or reclaim past glory, but old wounds are not easily forgotten.

In the future, an international monetary system that could blend the strengths of the Bretton Woods System and the floating exchange of today would be able to tackle the weaknesses of both systems while allowing for choice that individual countries desire. Finding such a solution would call for international cooperation but given that every country has its own interests along with international interests to tend with, such a solution seems elusive.

References:

Bordo, Michael D, Barry J Eichengreen, and National Bureau. A Retrospective on the Bretton Woods System : Lessons for International Monetary Reform. 1993. Reprint, Chicago ; London: University Of Chicago Press, 1993. https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c6876/c6876.pdf.

Bordo, Michael D. & McCauley, R. N. (2019). Triffin: Dilemma or Myth? IMF Economic Review, 67(4), 824–851. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-019-00088-y

Bretton Woods: Keynes versus White – OeNB. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.oenb.at/dam/jcr:a3d4ff9d-8108-4fa4-a5f1-2ea5d37c9794/Workshop_No18_05.pdf

Hallet, A. H. (2009). Smithsonian Agreement. In K. A. Reinert (Ed.), The Princeton encyclopedia of the world economy. (two volume set). (pp. 1292-1294). Princeton University Press. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utd/reader.action?docID=557122

Humpage, Owen. “The Smithsonian Agreement | Federal Reserve History.” www.federalreservehistory.org, November 22, 2013. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/smithsonian-agreement

Smaghi, L. B. (2011, October). The Triffin dilemma revisited. In Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at the Conference on the International Monetary System: sustainability and reform proposals, marking the 100th anniversary of Robert Triffin (1911–1993), at the Triffin International Foundation, Brussels (Vol. 3)

Smithsonian Agreement. (2003). In B. Etzel, Webster’s new world finance and investment dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from

https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/wileynwfid/smithsonian_agreement/0?institutionId=1164

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.) Nixon and the end of the Bretton Woods System, 1971–1973. (n.d.). Office of the Historian. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock

Why did the Bretton Woods Economic System end. Why Did the Bretton Woods Economic System End – DailyHistory.org. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://dailyhistory.org/Why_Did_the_Bretton_Woods_Economic_System_End