13 Finance: The Asian Financial Crisis

The Asian Financial Crisis is a classic example of a financial crisis and currency bubble. It was caused by mismanagement and speculation, what makes it notable however was the leadup, quick recovery, and global reactions to the crisis. Before the crisis many of the Asian economies looked to be infallible, growing at extreme rates for a sustained period. The most notable example of this is the Four Asian Tigers (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong) who all saw massive growth from the 1960s to the 1990s which was credited to Neoliberal policies such as a small welfare state, lax regulation, and low taxation. These factors also directly contributed to the financial crisis putting doubt into the veracity of these policies. These doubts are suspect themselves though due to several low-regulation solutions to the problems presented by the crisis and the very quick recovery after the crisis, credited to international intervention and resiliency within the economies themselves. In addition, there is inquiry as to how neoliberal the policies of those four nations and other Asian countries were. This prompts the key question of the crisis that remains to this day. Can the growth rates of the East Asian economies be achieved while avoiding the risks of systemic financial crises? The answer to this remains unclear, but what is clear is that there are numerous policy lessons to be learned from understanding the crisis. Some of these policy lessons have easy solutions that could reduce systemic financial risk, while others come with significant economic side effects. Drafting policy is important and could be used to prevent economic ramifications yet can be difficult to create and implicate. Regardless, the story, lessons, and ramifications of the crisis should be in any economist or policy maker’s tool belt.

Lead-up to the Crisis

In the run-up to the crash, a currency bubble was formed. A currency bubble is a situation where the value of a currency is artificially held high either by governments or the private sector. This can be done for monetary policy reasons, such as seeking to make imports cheaper or increasing exports. This can also be done by the private sector in a speculative cycle that causes the value to balloon. The Asian financial crisis was caused by both, the government provided fixed exchange rates meaning that they were perpetually artificially holding the value of the currency up and there was significant “hot money” in the private sector. Hot money is money that quickly moves around the market in search of returns. This can cause a standard hiccup in the market to spiral out of control as the hot money flows out causing a multiplicative effect on market movements. This can be useful when markets are moving up but as the bubble began to pop it made the crash much worse.

The exact date of the start of the bubble popping and the crisis beginning can be pinned to July 2, 1997. On that day, a consortium of speculators attacked the Thai Baht selling off lots of assets in the Baht and foreign investors sold their Baht reserves to convert into dollars. This forced the Thai government to drop their currency peg to the US dollar and it fell 16% that day and would fall over 50% in the following year. This was repeated throughout the Asian countries that fell victim to the crisis. Countries were put under further pressure due to China devaluing their currency the Renminbi, which in turn caused the Japanese currency, Yen to fall in value multiplying the potential gains from future attacks making them more common and large. This, in combination with increased American interest rates which created a strong dollar, meant that there were capital outflows that in turn caused the collapse of the currency bubble as people quickly sought to convert their Asian currencies to others due to the fixed exchange rates. The Asian governments were then unable to keep up with these exchange obligations and were forced to let the value of the currency float. These floating rates subsequently crashed, starting the crisis in earnest.

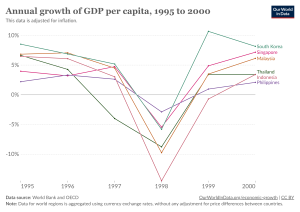

Another multiplicative factor in the crisis was the public and private debt load of the Asian countries. In the years leading up to the crisis, the GDP growth of these nations was massive, seeing rates as high as 10% year over year (see Figure 1). These rates were partially spurred by a high level of spending and borrowing. Companies would take out massive loans to invest in themselves and consumer debt became very common. This would not be a problem if growth continued but due to the currency crisis, it made it difficult for companies to repay their debts. Selling internationally became much less profitable and domestically the crisis was causing a decrease in spending. Thus, companies and consumers were forced to default on debts worsening the crisis.

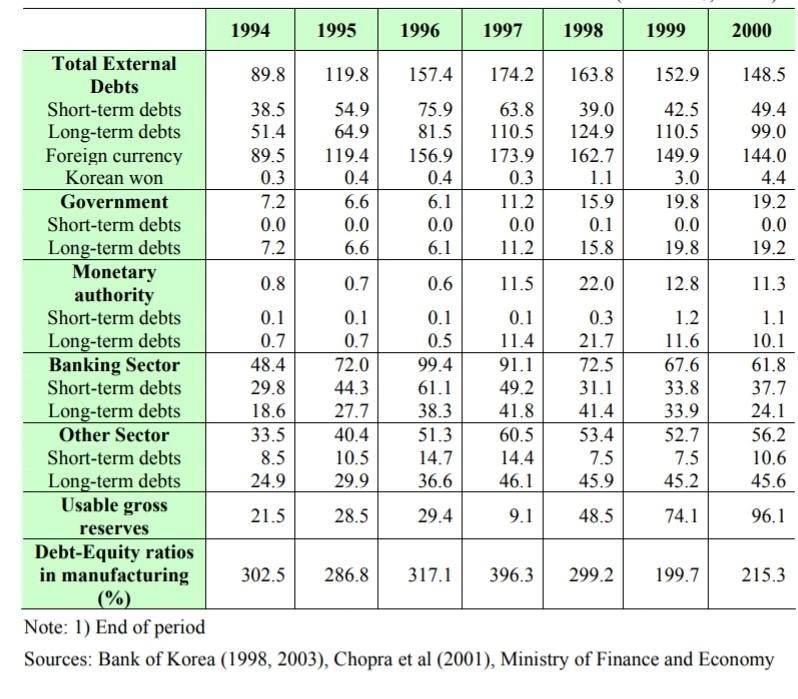

These debts proved additionally difficult as companies’ balance sheets were put under pressure. Previously sound investments and low levels of leverage (Leverage is taking out debt to invest in a speculative financial instrument in pursuit of higher gains. As the name suggests it increases both gains and losses.) turned into huge potential losses. These losses could normally be shored up with foreign investment, but foreign investment had dried up due to fear of the crisis. These balance sheet losses forced some companies to sell off huge portions of their balance sheets to get away from potentially bankrupting losses. Ironically these types of large selloffs multiplied the size of the crisis. All these different components would have continually built off of each other crashing Asian economies into the ground for potentially decades, much akin to the 2008 financial crisis, but luckily for these Asian economies, they held vast foreign debt. This debt may have been part of causing the crisis in the first place, but it also gave incentive to these investors to intervene.

IMF Intervention

The IMF was involved in the aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis in efforts to help stabilize the economies of the three main Asian countries affected, Thailand, South Korea, and Indonesia. The IMF was asked to step in by the suffering countries and help. The IMF contributed an initial amount of $35 billion to programs and to make policies that were needed to resolve the financial crisis. The IMF assisted in making monetary policies in the most severely affected Asian countries to stop the declining exchange rate of their currencies. In addition to assisting with financial policies, the IMF also helped with structural reforms to financial institutions in the countries. The IMF also assisted in closing insolvent financial institutions that would only cause further losses as well as attempting to stabilize institutions that were seen as potentially helpful in stopping the collapse of the economies. The structural reforms also included strengthening the financial supervision and regulation to prevent another crisis from happening in the future by trying to change the institutions fundamentally to prevent the same problems that caused the crisis from occurring again.

The programs the IMF put in place were less successful than they initially had hoped for due to many different factors including financial packages that were not delivered, problems with short-term debt collection, and an imbalance between them and the financial reserves the countries have. One of the main results of the IMF’s assistance in the financial crisis other than helping stabilize the economies in the affected countries was its laying of groundwork and recognition that they needed to prepare better and have more preparations in place in the event of further financial crises around the world. While the IMF policies and reforms were credited with helping the slow and eventual easing of the financial troubles found in Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia, they were deemed slow in actual effectiveness in helping resolve some of the fiscal issues that were plaguing the countries.

The effects of the IMF assistance to the countries led to their eventual recovery and have led to the increased recovery of the economies in both countries. In helping the countries that were most severely affected by the financial crisis the IMF helped put in place reformations and policies as well as establishing guidelines as to what worked and what didn’t in their effort to help. While the IMF provided funds and assistance to the countries many of the policies, they had pushed onto the countries were looked upon with caution because the IMF had previously made an economic crisis in Mexico worse in the short term before adapting things to make them more suitable and eventually help Mexico. While the fund was focused on helping the Asian countries, they applied measures that helped calm Financial Crises in Central and Latin American countries, to the Asian Financial Crisis, whose circumstances and causes differed.

In terms of the IMF’s response, the IMF’s remedies appeared to be ill suited for the case of the Asian Financial Crisis. During the earlier financial crises in the Central and Latin American countries, it was excessive government spending that played a role in causing the crises and led to effects such as inflation and trade account imbalances. The overall impact of these effects was the overvaluation of currencies and capital flight. In that case the IMF aimed for a reduction in government spending and utilizing improved tax collection to increase revenue as well as raising interest rates to keep funds within the countries and to prevent excessive speculation. The IMF also aimed to devalue currencies to encourage exports. These solutions were somewhat successful in countries able to implement them.

The Asian Financial Crisis however, possessed a different set of characteristics. For example, rather than recording deficits, government budgets reflected surpluses, not much price inflation, positive interest rates and account balances along with high saving rates. Furthermore, the Asian countries had thriving exports and domestic growth. Ultimately, what worked to cause the financial crisis was foreign capital flight and the IMF’s insistence, along with the international community including Europe, Japan, and the U.S., that the Asian countries liberalized capital markets was poor advice, especially since the Asian countries were not well-equipped to cope with large inflows of foreign capital.

In an article written by Deena Khatkhate for the economic and political weekly, she goes on to explain and provide insight into the reasons that the IMF intervention into Southeast Asia and the reform policies they started with would not be effective in handling the crisis. She explains that a large part of the problem in Korea was that many of the issues came from private sector debt and large companies and the IMF policies were garnered towards the public sector deficit, as was the case in Central and Latin America.

Other issues raised by the IMF investment into Southeast Asia was it caused a financial sector panic as the large inflow of financial packages and investment with ineffective policies set in place thwarted the IMF’s initial plan and forced them to reconsider what would work in the region. The Financial crisis started to tame itself when the IMF, Korea, and Thailand started to negotiate with foreign investors and banks in the private sector over short-term credit and converting some of it into medium-term bonds. Another policy that helped ease the crisis revolved around raising interest rates to a high level in order to try and stop the cycle of appreciation and depreciation from occurring. This policy ultimately helped stop the cycle and allowed the markets to stabilize and the currency rate to recover. Indonesia took a different method to halting their financial crisis and getting it under control. They redesigned the programs that the IMF had put in place and in this admitted that the original programs were the wrong type to tame the financial crisis. The redesigned programs that the Indonesian currency board and IMF put together were more focused on short-term debt repayment that would be at a fixed exchange rate. The IMF intervention and the policies and reformations they helped to implement have led to significant restructuring in the affected countries as well as holding the private sector and large corporations to stricter standards designed to mitigate the chances of a future financial crisis. The reformations and policies also put in place bureaucratic organizations designed to help enforce laws and regulations put in place during the financial crisis.

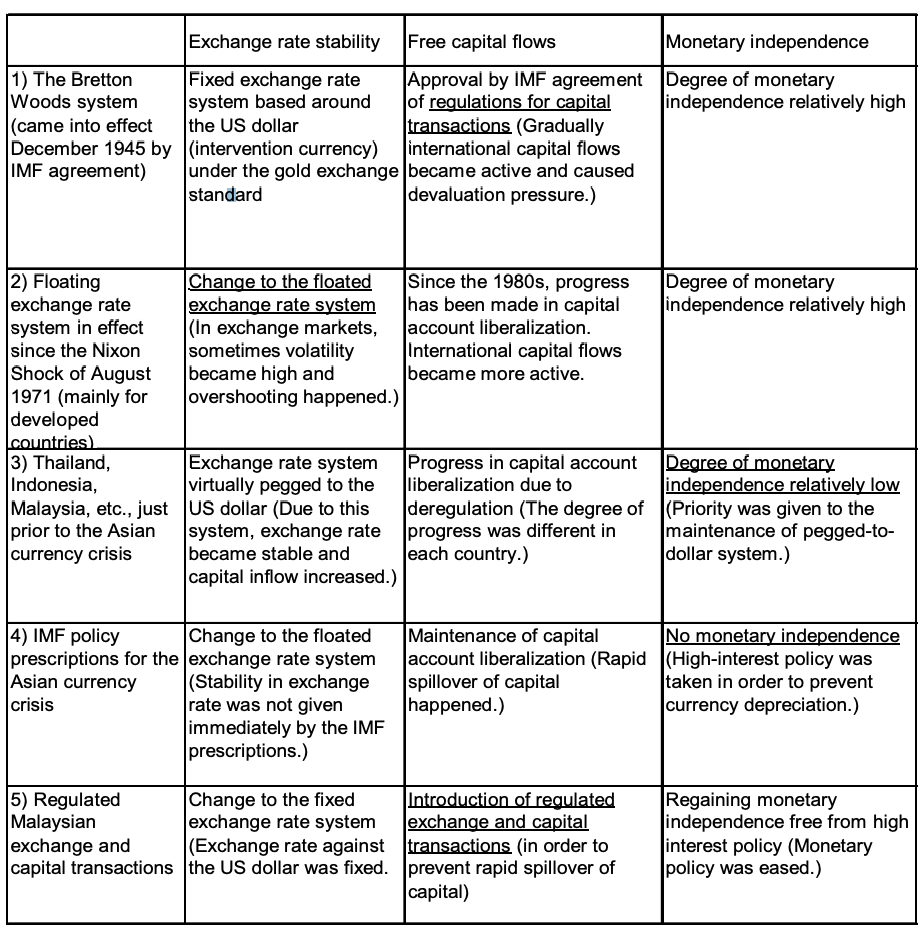

Therefore, the IMF failed to differentiate between cases such as Central and Latin America, and the case of Asia, misunderstanding that unlike the case of Central and Latin America, the Asian Crisis was a product of the Asian Countries inability to handle the large inflows of foreign capital and therefore implemented ill-advised measures such as raising interest rates and encouraging surpluses in the budgets, under the assumption that the case of the Asian countries were similar to that of the Central and Latin American countries and therefore this mistake on the part of the IMF helped lead to the crisis. We can link this back to the Mundell-Fleming Trilemma as the loss of monetary independence as a result of the Asian countries prioritizing a stable exchange rate and free capital flows. Due to the failure of the IMF in this case, the Asian countries were unable to regain confidence in the Asian economies and currencies leading to the crisis. The IMF’s decision to advise the cutting of spending, in the Asian countries who had budget surpluses had a detrimental effect on the economic crisis and reflected a misunderstanding, on the part of the IMF, as to what the problem facing the Asian economies were. Unlike Central and Latin America, the problems facing the economy were not a result of the government but because of the private sector and their imprudence.

Understanding the Crisis through the Mundell-Fleming Trilemma

The Mundell-Fleming Trilemma is an economic theoretical framework, the lens through which the Asian Financial Crisis, can be better understood. The Trilemma model states a country must choose between free capital mobility, exchange rate management and monetary autonomy and that a country’s government can only choose between two of these three things. This model can be applied to the case of the Asian economies because this model can be used to demonstrate that with the rise of capital mobility in the post Bretton Woods era, the governments of the Asian countries had to make a choice between independent monetary policy or exchange rate stability. This is why the Asian economies, including Thailand, South Korean, Indonesia and Malaysia, chose two out of the three options at different points in time, depending on the policy priorities of that given time. These policy priorities are best articulated by this table utilized by the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry of Japan shown below.

While the Asian Economies did not necessarily make a permanent or rigid choice of which of the three factors to maintain, the choice of which factors to sacrifice depended on the policy priorities of the specific time frame. At the time of the financial crisis, as shown on the table, the Asian economies made the choice of having a fixed exchange rate, pegging it to the US Dollar while pursuing capital account liberalization. This was done to incentivize foreign investment into the Asian economies, however as per the Trilemma model, that meant the Asian Economies sacrificed the ability to pursue independent monetary policies for the purpose of exchange rate stability open capital accounts.

Therefore, the impact of this was that when the Financial Crisis occurred, the Asian economies, having sacrificed an independent monetary policy could then use monetary policy to combat the crisis, worsening the impacts of the crisis as a lack of independent monetary policy hindered the Asian countries from being able to respond effectively to the crisis and stabilize their economies.

Country Case Studies

The countries involved within the Asian Financial Crisis had their own unique set of circumstances and ways of recovering from the crisis. The destabilization of the Thai baht surged the recession of many economies across Asia. The vulnerabilities of many different countries were shown and thus needed a fix. The IMF was a key player in revitalizing many economies across the continent. Some of these countries include Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

Thailand

In 1996 Thailand’s booming economy began to come to a simmer by late 1996 they began to realize the economy was headed for a decline.The worst estimates were still far off from the true economic decline they would soon face. In Early 1997, Thailand was warned of impending doom. Investors were speculative of the baht and the reserves of the government were depleting. The country ran out of foreign currency to exchange and thus the crisis started. Markets crashed, investors pulled out, and the economy suffered heavily. As a result of the country going into panic mode, the Prime Minister General of Thailand Yongchaiyudh resigned due to his inability to form any sort of macroeconomic policy that would aid the country. The Bank of Thailand on the other hand was viewed as stable and a very respectable establishment. They managed their reserves very well and instated very cautious macroeconomic policies that managed inflation and currency exchange rates. Nonetheless, they still could not avert the crisis.

The IMF stepped in and created a set plan for Thailand. They needed to regrow financial institutions as there were around 56 closures across the country. Restructuring the budget of the government provided for additional funding in crucial areas that needed support. They amped up the private sector of the economy and improved the current account position. By doing this, they were attempting to encourage foreign investment in the country and gain back capital for the country. They focused on monetary policy that could strengthen currency exchange rates and also heavily restructured the financial policies by intervening in weak banks and increasing capitalization in the banking system. As time went on, Thailand finally started recovering around late 1998 as their GDP grew almost 4 percent in 1999.

Indonesia

Like Thailand, the start of the crisis had parallels to what happened in Thailand. A poorly structured financial sector contributed to the fall of the economy. The sector was undercapitalized and was highly neglected due to the bank’s abysmal decision-making plummeting the sector’s financials. Doubts were cast on the government to maintain the stability of the currency, as short-term private sector debt arose. Inflation hit and the value of the rupiah plummeted. The value of the Rupiah went from 2,500 to 10,000 Rupiah per U.S dollar. The society of Indonesia suffered because of the economic turmoil. The political tensions from before the economic collapse had worsened and led to an increase in crime, violence and corruption. Safety nets were instituted within the country to ease economic hardship and strengthen the economy. These safety nets were not enough however, and rife with corruption. As the crisis worsened and society became more unstable this would ultimately lead to the end of the Suharto Government itself. As a result of this, the President of Indonesia, Suharto resigned.

The IMF came in towards the end of 1997 and established a three-year plan to restore the economy. The first step was the restoration of the currency. They implemented firm base money control as a primary focus. To anchor banking sector reform, they wanted to create an effective bankruptcy system and bring in governmental stability. Progress was stagnant throughout the initial stages of the program as scandals within the banks impeded progress. This eventually led to the suspension of the program in 1999 and the IMF needed to institute a new plan to aid the country. A newly elected government was able to efficiently implement a new plan that brought in 10 billion USD to aid the program. They focused on the banks by having similar goals as the program that preceded it but with increased supervision of the banks and the government. The economy was able to recover but inflation never fully recovered.

South Korea

Initial thoughts of the crisis led many to believe that Korea would not be impacted by the ramifications of the crisis started by the fall of the Thai Baht. The Korean economy was one of the strongest in Asia as its GDP was around 450 billion USD. They had a stable inflation rate and their currency exchange rates remained relatively stable. Despite this strength, debt was the factor that led to their collapse as they faced pressure regarding their payments. The debt accrued since the early 1990s had reached a record high. In addition to the debt bubble another contributing factor for the collapse was the deregulation of the banking sector. Specifically, the short term borrowing side. No or little regulations regarding short term lending led banks to use short term lending to finance long term investments.

In Late 1997 the IMF came to help with Korea’s economic struggles. The IMF decided to focus on macroeconomic policies. They wanted to aid the Won by implementing strategies to control the interest rates. This attempt stabilized the currency and the IMF shifted its focus toward structural reform. This featured retooling the corporate and financial sectors and regaining capital back into the economy. They wanted to restore capital by freeing assets to support stability. The Korean economy recovered quickly leading up to 1999 and 2000.

Malaysia

The Philippines and Malaysia were affected quite differently than the other Asian countries. Their macroeconomics varied significantly from the Asian countries as they were much stronger and more secure in the areas of fiscal responsibility, for example, debt and inflation. Moreover, they had a stable corporate sector and banking system allowing for ease of regrowth when the crisis hit. The IMF supported this as in the early 1990s, macroeconomic restructuring was a primary focus of theirs. [Fig 6: Mahathir Mohamed (sp)]

When the crisis hit the initial fall of the economy was similar, as the fall of the Baht was a catalyst and inflation still hit. Investors withdrew, leading the economy to further tank and become unsupported. The stock market saw a ton of red with the currency’s destabilization. This led the governments of Malaysia and the Philippines to intervene and not have the IMF intervene as heavily as they had to in other countries.

Effects and Implications

The impact that the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998 can be seen through not simply an economic perspective, but a political and social perspective as well. These impacts and effects were able to be seen on a small regional, national, and global scale. The financial crisis caused a lot of havoc as it was claimed to be homegrown and due to neoliberalism, thus many placed the blame on state practices, arrangements of national governance, and capitalism. The aftermath of the Asian Financial Crisis resulted in currency crashes and market crashes in several countries that became known for their economic progress at the time. The countries that experienced the crisis enjoyed a large economic growth in the years leading up to 1997 which caused such effects to be more visible from inside and outside perspectives.

Through a political perspective, Indonesia was one country that experienced examples of what can be described as a main erosion of authority. Suharto was a previous President of Indonesia and had led the country for over 30 years. Even with thirty years of knowledge under his sleeve, the crisis ultimately led to his fall in leadership. There was controversy when it came to his presidency which involved corruption and favoritism, ultimately alienating those in status classes and groups such as business circles. These issues were pushed away because of the main focus that Suharto had allowed the country to grow economically. The rates of growth played a role, along with the strong grip of the government, as they had allowed Suharto to remain protected until the Asian Financial Crisis began making its way to Indonesian currency and markets. The once prevalent growth of the country was eroded due to the currency crisis, and the value of the Rupiah declined immediately which deeply impacted the national economy. Indonesia had an issue it had not dealt with before and due to that, they had to change their way of living like many other countries that experienced the effects of the crisis. Within less than a year, in May of 1998, demonstrations and protests began taking part to show the public was no longer on Suharto’s side. The presidency of Suharto ended on May 21 almost immediately after he lost support from the military.

In the social life aspect, the sudden change, the way of living had to be adjusted to fit with the new situation. One country in which this is visible is South Korea, as it went through an increased inequality when it came to income. The rate of poverty right before the crisis was at 3.0 percent in 1997 but rose to 6.4 percent at the beginning of 1998 and grew to 7.5 percent towards the end of that same year. This rate could have been possibly higher as the survey of Urban Workers’ Survey of Income and Expenditure does not include those unemployed or those in rural areas, which are more prone to fall under the poverty rate. Even without the data that would have a greater impact on the result, the difference within the same year of the crisis is huge. Another example would be Malaysia where the poverty rate was decreasing right before the crisis however following the incident, the poverty rate began to be reported with a quick increase. On a separate note, countries also endured regional impacts, one of which was

Thailand. The Socio-Economic Surveys collected data in Thailand throughout the years 1996 1998 in rural and urban regions to showcase income differences. The Northeastern part of the country had the most noticeable sharp decline, but the inner vicinity of Bangkok had a national average of 3.3 percent increase. With several more countries involved, it is evident the effects were not minor and were not seen years later, the impact was clear and made its way into everyday society and people’s way of living.

On the financial side, stock markets experienced large shifts in several countries throughout 1997 to 1998. The biggest decline was Indonesia which experienced an 80% decline, closely after Malaysia underwent a 74% decline, the Philippines with 54%, Thailand with 42%, and South Korea with 29% (Lairson and Skidmore 2003, p. 405). Debt increased due to borrowed foreign currency and left countries stuck in unprecedented situations. These numbers were a result of what can be divided into three explanations, investor panic, unanticipated shocks, and what can be described as weakness and mismanagement of domestic economies and the structure they are in.

As with many issues, the ability to pinpoint the explanations allowed for lessons to be learned. One crucial aspect would be the accurate spread of information to allow for transparency. Lack of information and accuracy leads to panic amongst investors, companies, governments, and people. The panic led to options being taken with minimal regard for the events that would follow. International investors already had restricted information in markets which led to panicked decisions when more information was shared, this resulted in issues arising. Regulations and proper management are important as well, governments should be able to calculate risk and make choices with that in mind. Fixed exchange rate regimes can contribute to crises. The countries involved already had weak banking sectors which made the impact more costly because of interest rates. These along with other lessons can be taken from what occurred during the Asian Financial Crisis. The effect of this crisis left ripples not just on a small scale, but on a much larger one instead.

The major implications of the Asian Financial Crisis are lessons about currency policy and reducing systemic financial risk. In the realm of currency policy, it was shown that while artificially holding the value of your currency high can increase economic growth and have trade benefits it creates a litany of systemic issues. If countries are to peg the value of their currency, then they should ensure that they have vast reserves for times of crisis and take careful monetary policy steps to reduce the likelihood of such crises. The much more reasonable and popular step is to let the value of the currency to float with the ability of a central bank to intervene, in some cases majorly. This allows for a steady decrease or increase of value in the currency to happen safely while maintaining much of the ability to modify its value to fit the policy priorities of the government. The other major lesson is the regulation of speculative markets. While the crisis was inevitable with the former policy positions of the countries it was spurred by unregulated speculators seeking to turn a profit. There is no need to completely shut down such markets but low levels of regulation such as financial disclosures before large moves and cracking down on investor cartels and insider information would do much to stem the risk of these markets. Some of the broader risks of quick growth and debt load are more difficult to parse and are still being studied today. With time, it may be possible to design an economy that is both capable of explosive growth and resistant to systemic financial risk, but for now, we must make wise policy decisions maximizing one while minimizing the other. The Asian Financial Crisis is a perfect lesson in what not to do before a crisis while being an excellent example of what to do after a crisis. We shall continue to use it as an important piece of evidence in our policy-making toolkit.

Bibliography

Asian Development Bank, 23 Feb. 2015, https://think-asia.org/handle/11540/2484?show=full.

Ba, Alice D.. “Asian financial crisis”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 13 May. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/event/Asian-financial-crisis. Accessed 20 April 2022.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “B.J. Habibie”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 7 Sep. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/B-J-Habibie. Accessed 21 April 2022.

Bugge, Victor. 1997. Carlos Menem with Chavalit Yongchaiyudh. https://openverse.org/image/b8fabdbf-15f6-49f6-931d-043ac625a98f.

Essential Action. n.d. “How the IMF Helped Create and Worsen the Asian Financial Crisis.” Accessed April 24, 2023. https://www.essentialaction.org/imf/asia.htm.

Evers, Joost. 1970. Suharto, President of Indonesia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Den_Haag;_v.l.n.r._Prins_Bernhard,_President_Soehar to,_mevrouw_Soeharto,_koningin_Juliana.jpg.

Finance and development. Finance and Development | F&;D. (n.d.). Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2008/06/khor.htm

Hale, G. (2011, February 28). Could we have learned from the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98? Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.frbsf.org/economic- research/publications/economic-letter/2011/february/asia n-financial-crisis-1997-1998/

Katz, S. Stanley. 1999. “The Asian Crisis, the IMF and the Critics.” Eastern Economic Journal 25 (4): 421–39.

Khatkhate, D. “East Asian Financial Crisis and the IMF: Chasing Shadows.” Economic and political weekly 33.17 (1998): 963–969. Print.

Knowles, James C., et al. “Social Consequences of the Financial Crisis in Asia.” Think Asia,

IMF Staff. “Recovery from the Asian Crisis and the Role of the IMF — an IMF Issues Brief.” International Monetary Fund, June 2000, https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2000/062300.htm#VI.

Sharma, Shalendra D. The Asian Financial Crisis : Crisis, Reform and Recovery. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2018. Print.