6 Trade: Preferential Trade Agreements

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should…

- Understand why states are politically interested in joining preferential trade agreements.

- Understand the economic impact of preferential trade agreements.

- Recognize the difference between trade creating agreements and trade diverting agreements.

- See how preferential trade agreements interact with international institutions like the World Trade Organization.

Overview

Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) are agreements between two or more countries to grant preferential treatment to each other’s goods and services by reducing tariffs and other barriers to trade. PTAs are a crucial component of international trade policy in the 21st century. They are intended to promote trade and commerce among their members, but they also discriminate against trade with non-members. In the past, it seemed possible that PTAs would decline in importance with the emergence of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the advent of the modern global trade system. However, PTAs today are more important to understand trade than ever before, because they increasingly constrain policies that are often viewed as unrelated to trade.

Modern PTAs come in two primary forms. Many PTAs are free-trade areas, where members mutually lower tariffs and trade barriers, but retain authority over their trade controls. A customs union is another form that reflects a deeper level of integration, where members cede trade control power to a supranational organization and unify their external trade controls. Notably, PTAs are predominately regional arrangements. According to Dadush and Prost (2023), “the most prominent and systemically significant PTAs are mega-regional agreements” such as The European Union or NAFTA. Mega-regional agreements now include countries that account for around 78 percent of world GDP (Dadush and Prost 2023).

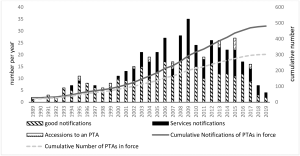

As of 2021, about half of world trade has taken place under some form of PTA (United Nations 2023). WTO data shows that around 82 PTAs were in force worldwide prior to 2000. Three times more PTAs have been in force over the last 20 years (Figure 1). This data shows that regional economic integration has increased after 2000, and the common trend now is an active wave of PTA emergence and formation. Overall, signing new PTAs occurred in a much larger proportion as opposed to accession to an existing PTA (Figure 1) (Yao et al. 2021).

It is important to consider the global implications of PTAs when evaluating their total economic impact. While PTAs provide benefits to their member countries, they should not be regarded as an alternative for the modern global trade system, including institutions like the WTO. Instead, they should be seen primarily to facilitate regional trade integration, and provide increased flexibility and exclusive benefits for member states.

This chapter will explore the political rationale for the creation of PTAs, evaluating their relationship with ideology and alliances. It will examine the economics behind PTAs, and discuss the two general economic outcomes that these agreements produce. It will also examine PTAs in relation to the modern global trade regime, and will explore the relationship between PTAs and great power politics. Three included case studies will also provide different perspectives on PTAs in different stages of formation and collapse. These modern case studies include the European Union, illustrating PTA creation and development, NAFTA and USMCA, illustrating PTA renegotiation and change, and the United Kingdom’s recent withdrawal from the European Union (BREXIT), illustrating PTA collapse, and potential harms on integrated economies.

Politics of PTAs

A PTA’s ultimate goal is to provide selective trade benefits to member states, which sometimes comes to the detriment of non-members. Consequently, the political rationale for creation of PTAs is often nationalistic in nature. States seek to strengthen or maintain their international position, maintain established trade linkages, and access new markets with these agreements. Some states use PTAs to divert existing routes to politically advantageous locations. These agreements are strategically oriented with the intention of gaining political influence or creating new supply chains in advantageous regions. There are two main ways that preferential trade agreements may be crafted in order to achieve this.

First, a trade agreement may protect industries within the PTA’s member states. Agreements with this goal may include a rules-of-origin clause. These clauses establish rules that determine the legal origin of products, enabling countries to benefit from lower tariffs and duties on these items that are produced within the trade area. One example comes from NAFTA, where cars were required to have a 62.5% North American content to benefit from the preferential treatment spelled out in the treaty (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020). By requiring cars to have a certain level of North American content to benefit from preferential treatment, NAFTA countries are aiming to draw increased economic activity in the manufacture of these cars to themselves. Overall, these PTAs aim to promote low tariff trade among member states for products they create, while also protecting and strengthening domestic industries within the free trade area.

Second, states frequently use PTAs for trade diversion to strategically benefit themselves or their geopolitical partners. States may choose to negotiate a PTA with a country or countries with the primary goal of exercising influence, gaining favor, or isolating a targeted state. PTAs do this by reducing trade with non-members, while simultaneously lowering trade costs for members. A modern example of the U.S. negotiating a PTA with the goal of exercising influence is the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP. Created in 2016, “The TPP could help to address these grievances by diverting trade away from China and directing trade toward other countries, such as Australia, that enjoy more friendly relations with the U.S” (Chow 2016). The trade agreement was made with the containment and exclusion of the People’s Republic of China as a chief motive.

States are more comfortable with their trading partners making gains from trade when the two states share an ideology or political goals. States are more wary, however, when the trade beneficiaries are ideological or political rivals. Many PTAs have this sort of alliance ideology at the heart of the agreement. States use economics to leverage influence with allies and enemies alike, and PTAs are an effective tool for this. States tend to economically support political allies with preferential trade, rather than political rivals. States are more comfortable with other powers making gains from trade if the partner powers have the same policy goals; however, hesitancy would be present when hostile powers benefit from trade. If two states with the same policy goals mutually benefit from trade, then the two states would use their surplus resources in cooperation. However, should two hostile nations mutually benefit from trade, then they would use their surplus resources in competition.

Economics of PTAs

PTAs can be classified broadly by their economic impact. These agreements are either trade creating or trade diverting. Trade creation refers to a system focused on removal of obstacles to trade, such as tariffs, quotas, and nontariff barriers. New international firms entering the market due to these lower barriers creates competition, new opportunities to sell abroad, and cost savings for both firms and consumers. This competition encourages a more efficient allocation of resources in the economy, raising the average productivity of businesses and industries in member states. Through this increase in productivity, trade boosts the overall economic output, workers’ average real wage, and a state’s general welfare. Consequently, there is an increase in the variety of products available for purchase, because of the lower prices for goods and services. These agreements enable states to harmonize laws and regulations, which make the costs of operating businesses in other countries similar to those costs in their own state. Easing regulations on foreign investment and providing improved legal protections for foreign investors facilitates greater investment by states.

Trade diversion is an economic behavior involving diversion of trade from countries that produce goods efficiently to countries that produce the same goods relatively inefficiently. This may occur through the formation of a PTA, when preferential treatment is granted to partners. PTAs sometimes have a diverting effect on trade, though this is not often the intention of the agreement. Ghosh and Yamarik (2004) find that PTA membership lowers trade outside the PTA bloc by 6 percent. Acharya et al. (2011), as cited in the World Trade Organization’s World Trade Report (2011), analyzed 22 PTAs and found that 5 of them caused trade diversion with an external third country, and 3 caused trade diversion within the PTA. These statistics show that trade diversion is a consequence of some PTAs, regardless of the goal for these agreements.

One example of trade diversion occurred during the Tequila Crisis, also known as the Mexican Peso Crisis. This was a currency devaluation crisis in 1994 that resulted in huge revenue losses for the Mexican government. In response to this crisis, the Mexican government imposed tariffs on imports entering Mexico. These restrictions exempted imports under NAFTA, which precluded such tariffs. These tariffs affected all non-NAFTA exports to Mexico, particularly East Asian exporters. Consequently, Mexican trade with NAFTA members grew, while trade with East Asian exporting states declined. This case shows how PTAs may result in trade diversion that exclusively benefits PTA members (Krueger 1999). Another example of trade diversion is the European Union’s application of common agricultural policy towards nonmembers. This policy involves increasing tariff implementation outside the bloc. It has been shown that as the rate of discrimination (tariffs) against non-EU imports increases, imports from non-EU states decrease. This shortfall is then made up by EU members who do not face the same duties as non-EU states.

Two very similar agreements can be contrasted to illustrate the difference between trade creating and trade diverting PTAs. One modern trade creating PTA is the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA). A study conducted by Clausing (2001) found that the agreement increased US imports from Canada, but did not divert US imports away from other US trading partners. Similarly, the CUSFTA study by Trefler (2004) confirms the finding that trade creation outweighs the trade diversion effect. Conversely, the CUSFTA successor NAFTA is largely trade diverting. A study by Romalis (2007) of NAFTA uses EU trade data to conclude that NAFTA is net trade diverting, concluding that the EU would see trade growth in the counterfactual world where NAFTA does not exist. Romalis does note, however, that the welfare costs of NAFTA are rather small.

There is evidence on both sides as to whether PTAs overall create trade or divert trade, with mixed evidence when looking at the aggregate welfare generated by PTA’s. Two studies, both using a gravity model, Magee (2008) and Carrère (2006), came to opposite conclusions. Magee’s study used data for 133 countries in the 1980-1998 period, including several fixed effects to capture the counterfactual: what would happen to trade if there were no PTAs. He finds that the average impact of PTAs on trade flows is small – only 3 percent – and that, on average, trade creation exceeds trade diversion. In comparison, Carrère’s study on PTAs found that 130 countries from 1962 to 1996 have generated a significant increase in trade between members, often at the expense of the rest of the world, suggesting evidence of trade diversion. These differing results show that the data is mixed on whether PTAs generally create or divert trade overall. The effect of these agreements is likely highly contingent on the specific provisions contained in each.

PTAs and Global Trade

Despite generally being regional agreements, PTAs are important to consider in the broader context of world trade. This is particularly true for their relationship vis-à-vis the WTO. Preferential trade agreements typically do not include most-favored-nation (MFN) clauses, a central provision in WTO negotiations, which stipulates that states must treat all their trade partners equally, and one partner should not receive more favorable terms than any other. Therefore, no country may give another preferential treatment in regard to their imports. Two main exceptions to this provision exist: aiding in poorer countries’ economic development, and comprehensive trade agreements that foster economic integration (i.e., EU, NAFTA, PTAs in general).

Today, all WTO members are part of at least one PTA. PTAs are similar to the WTO in facilitating trade liberalization, but differ in terms of scope, regionality, geopolitical structures, and scale of operations. PTAs are seen by some states as a hedge against potential instability in the global market, particularly to guard against global economic crises.

The WTO’s transparency mechanism directly relates to PTAs. This non-binding guideline stipulates that countries should announce their intention to join a PTA, and that they disclose the terms of the agreement to the WTO. The information provided by this mechanism is used by WTO to develop “best practice” guidelines on various aspects of PTAs. Both traditional and new practices include environmental protections, labor rights, intellectual property and related preferences. Best practice guidelines like these would place non-binding pressure on WTO members to not deviate from the international norm. This would much more effectively aid in achieving the goals of trade liberalization and development than the old binding obligations that do not keep up with the fast-paced evolution of PTAs.

The modern global trade system is complex and is always evolving. Whereas some believed the WTO would forever be the center of this international trade system, recent events, such as the United States blocking the appointment of new appellate judges for the dispute resolution court (Blenkinsop 2023), have significantly weakened the WTO’s position. It is possible that PTAs may grow even more in value in the future due to the WTO’s diminished role.

Case Studies

NAFTA/USMCA

The first negotiations for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) began in the early 1990s, under H.W. Bush administration. By January 1, 1994, the accord was signed by president William J. Clinton and officially implemented into the law. NAFTA was important for all participants, because it was the unprecedented free trade agreement (FTA) between two wealthy countries (U.S, Canada) and a lower-income country (Mexico). It also established precedents for setting new rules on future trade agreements on problems important to the U.S. These issues would include provisions on agriculture, intellectual property rights protection, investment, services trade, labor, dispute settlement procedures, and the environment (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020).

NAFTA’s liberalizing measures allowed gradual elimination of all tariff barriers, as well as most nontariff barriers on services and goods originated and traded within North America. After the agreement entered into force, trade volume between NAFTA members more than tripled, forming consolidated production chains among all three states. Many trade policy experts emphasize the success of NAFTA with its massive trade expansion and provision of effective economic linkages among the parties. Further successes include increased availability of lower cost consumer goods, increased variety of products, and improvement of both working conditions and living standards. However, some experts criticize NAFTA for decrease in average U.S wages, disappointing employment trends, and for lack of improvements in environmental conditions and labor standards abroad (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020).

Initially, NAFTA helped to “lock in” investment liberalization attempts taking place at the time, particularly in Mexico. Since the agreement facilitated closer U.S. relations with both Mexico and Canada, it may have simultaneously boosted investment trends and ongoing trade. By the time NAFTA was implemented, the U.S. already had low tariffs on most Mexican products. On the contrary, Mexico had the highest level of tariffs and nontariff barriers among the three countries due to its previous protectionist trade policies. After NAFTA, both the U.S. and Canada gained easier access to the Mexican market, which happened to be the major export market for U.S. services and goods (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020).

Additionally, NAFTA opened the U.S. market for greater volume of imports from Canada and Mexico, which formed one of the largest free trade regions globally. NAFTA also promoted discussion and cooperation among the members on broader aspects of relationships. These aspects would include industrial competitiveness, regulatory cooperation, border environmental cooperation, and security (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020).

U.S. trade with NAFTA members expanded tremendously after the agreement’s implementation, growing more rapidly than trade with most other countries. U.S. total merchandise imports from NAFTA partners increased from $150.9 billion in 1993 to $677.9 billion in 2019 (349%), while merchandise exports increased from $141.8 billion to $548.8 billion (287%) during the same time period. Trade in services among NAFTA parties increased as well (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020).

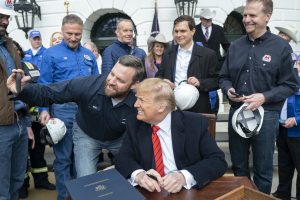

In May 2017, the Trump Administration notified the Congress of the president’s intent to initiate talks with Canada and Mexico on NAFTA’s modernization and renegotiation. The disputes officially began in August 2017. As a result of these negotiations, United States-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) was “born” and further signed by Trump and implemented on January 29,2020. The agreement must be ratified by all three parties in order for it to enter into force.

Also, a country’s laws and regulations that meet their USMCA commitments must be in effect. After all these requirements were met, USMCA officially entered into force on July 1, 2020 (Villarreal and Fergusson 2020).

USMCA retained most of NAFTA’s market opening regulations and other regulations. However, it made significant adjustments to auto rules of origin, government procurement, dispute settlement provisions, investment, and intellectual property rights protection. (Office of the United States Trade Representative 2020).

For example, according to the Congressional Research Service, USMCA tightened auto rules of origin by including (1) new motor vehicle rules of origin and procedures, including product-specific rules, and requiring 75% North American content; (2) for the first time in a trade agreement, wage requirements stipulating 40%-45% of North American auto content be made by workers earning at least $16 per hour; (3) a requirement that 70% of a vehicle’s steel and aluminum must originate (melted and poured) in North America; and (4) a provision aiming to streamline the enforcement of manufacturers’ rules of origin certification requirements.

Key debates for Congress in relation to USMCA also involved worker rights protection in Mexico, access to medicine, intellectual property rights provisions, the enforceability of labor and environmental provisions, as well the constitutional authority of Congress over international trade and its role in revising, approving, or withdrawing from the agreement. (Office of the United States Trade Representative 2020)

Current data from the Office of the United States Trade Representative shows that U.S. goods exports to USMCA in 2022 were $680.8 billion, up 16.0 percent ($94.1 billion) from 2021 and up 34 percent from 2012. U.S. goods imports from USMCA totaled $891.3 billion in 2022, up 20.5 percent ($151.5 billion) from 2021, and up 48 percent from 2012. U.S. exports to USMCA account for 33.0 percent of overall U.S. exports in 2022. The U.S. goods trade deficit with USMCA was $210.6 billion in 2022, a 37.5 percent increase ($57.4 billion) over 2021.

Overall, it can be noted that even though USMCA retained a major part of NAFTA, this modernized agreement provides more balanced and reciprocal trade, both supporting growth of the North American economy and maintaining the flow of high-paying jobs for Americans.

European Union

During the period after World War II the world saw many transformations both politically and economically. Many countries gained their independence from their former colonial powers, a conglomerate of socialist states was created, and the world had both the conditions for prosperity and peace. Of these conditions that are of particular importance was the ravaged economy and destruction of the European economies after World War II. To get the global economy back on its feet, the US being one of the only states at the time within the capacity to afford reconstruction and reintegration efforts, developed a policy. This policy was in the form of a plan named the Marshall Plan, and involved funds totaling $ 13.3 billion (National Archives). The Marshall Plan allowed European countries particularly Western European countries to rebuild their economy and reenter the global economy. The Marshall Plan would provide both the capacity and foundation for the formation of the European Union (EU).

The European Union (EU) is the most prominent example of a Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) today. It was originally conceived as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) at the end of the Second World War. This was facilitated by the Schuman Declaration in May of 1950 and consisted of the countries Luxembourg, Belgium, Italy, West Germany, the Netherlands, and France. One of the initial ideas behind its formation was that if two countries, like France and Germany had integrated economies, it would be very difficult or almost impossible for them to go to war with each other again. To add further pressure to this, coal and steel were two of the most important industries affecting the economies of the war and its immediate aftermath. It was initially targeted as it only conceded a very specific and limited amount of autonomy while furthering the goal of European peace.

In 1957, the members of the ECSC met in Rome and signed The Treaty of Rome. This created the European Economic Community (EEC). The treaty laid out the main principles of the EU today, one of which is the common market. To achieve a common market required the implementation of a customs union. The six aforementioned countries were surrendering an unprecedented amount of sovereignty and intertwining their fates in a way few countries have done while maintaining independence.

Many other European countries at this time were either unable or unwilling to join the EEC. A huge factor for many was the amount of sovereignty being surrendered in a customs union. Seven of these other European states met in Stockholm in 1960 signing the Stockholm Convention creating the European Free Trade Association (EFTA). These countries were the United Kingdom, Norway, Portugal, Denmark, Austria, Switzerland, and Sweden. The EFTA removed many trade barriers within member states but did not create a common market or impose a customs union. This left the sovereignty of its members’ foreign policies intact. Most EFTA members left the association to join the EEC and other European Community treaties such as the European Economic Area (EEA) and the Schengen Agreement. Four Western European countries have chosen not to join the EU: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. These countries operate independently of the EU and have decided their sovereignty is more important than the potential benefits of joining the EU (Zaken 2021).

The EEC evolved with the creation of the EFTA, EEA, and the Schengen agreement leading to the creation of the European Union in 1993 containing 27 member states. The market has been further integrated through the use of a common currency, the Euro. This is managed by the European Central Bank, and constricted members’ abilities to use currency to help exports. There are numerous institutions in place now as well which make the trade decisions for the whole of the block. Since the inclusion of treaties like the Schengen agreement which was signed in 1985 and implemented in 1990. The Schengen agreement eliminated law enforcement controls at the borders between members of the treaty, and countries’ trade policies are largely now decided in Brussels. The countries of Cyprus, Ireland, and Lichtenstein are not part of the Schengen agreement. Additionally, the Schengen agreement allowed for the free flow of labor capital across the participating states further bolstering the economic production of the EU (European Commission 2024).

Many of the foundational principles that the EEC, EFTA, EEA, and the Schengen agreement utilize have been integrated into EU law. This has made the EU the biggest PTA currently in existence. States that subscribe to the EU must oblige the laws and policies of the organization in exchange for benefits that come in the form of currency stabilization, economic market access, and labor and economic capital to name a few. The EU fosters trade creation for the states that subscribe to it while isolating those who do not. As of 2024, the EU has PTA agreements with 74 countries around the world. In 2023, the EU made over 2 trillion euros in trade deals (European Commission 2023). In the last two years, the EU has increased its exports “… in pharmaceuticals to Vietnam increased by 152%, cars and parts to South Korea by 217%, EU exports of meat to Canada increased by 136% and EU services’ exports to Canada rose by 54%.”(European Commission 2023). Additionally, when compared to US PTA’s, the EU has a greater ratio of exports of 70% to 40% as well as a greater value of $3.4 trillion compared to $0.52 trillion (Ahearn 2011). This further exemplifies the power that the EU has in shaping trade policy and creation. The EU continues to develop PTA agreements with other states outside the region in an ongoing process to both liberalize and create trade opportunities for its members. Overall, the EU serves as a large PTA that influences the political and economic policies of Europe by arranging enticing benefits for those who subscribe to its tenets. Recently, the United Kingdom has left the EU and lost access to all the PTAs the EU has negotiated. This has caused some repercussions and a focus on negotiating new PTA’s with the states they have lost access to. This process will be detailed in the subsequent case study.

Brexit

This chapter has largely focused on how PTAs facilitate the deepening of economic ties and trade relations between their member states, but what happens when an integrated economy decides to leave a PTA? The case study of Brexit, the United Kingdom’s (UK) exit from the European Union (EU), one of the largest PTAs in the world, is perhaps the best model to examine. This case study will discuss the history and politics behind Brexit, the economic impact of the UK’s decision to leave, and will also briefly discuss the effect of the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, the free trade agreement currently in place between these actors that developed from Brexit negotiations.

On June 23, 2016, the UK officially voted in a referendum to leave the EU, decided by a vote of 52 percent to 48 percent. After several more years of tumultuous negotiations internally in the UK and between the UK and the EU, the UK officially left the EU on January 31, 2020 (Hayes, 2024). The chief inciting issues to the decision to finally hold a referendum were prior European crises, particularly the European debt crisis and the European migrant crisis. A public loss of confidence occurred, with UK voters coming to disbelief in the ability of the EU to manage these sorts of crises and believing that European economic decision making was not necessarily good for the UK (Luo 2017).

Out of all the countries in the EU, the UK was perhaps one of the best positioned to leave. Unlike the other major European economies of Germany, France and Italy, the UK had never accepted the same high level of European integration and maintained opt-outs on many core pieces of EU policy. The UK never acceded fully to the Schengen Agreement, which would have eliminated border controls between the UK and the EU. Additionally, and arguably more significantly, the UK never adopted the Euro as its currency, instead retaining its own Pound sterling. A deeper economic and political integration would likely have further complicated an already fraught withdrawal process.

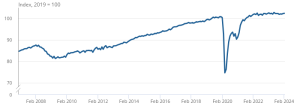

Initial projections of the cost of Brexit on the UK economy were somewhat apocalyptic. Then Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne infamously warned of a potential 10-18% decline in UK home value as an immediate consequence of Brexit (Mance 2016). Other estimates predicted losses for the remaining EU countries at between 0.08% and 0.44% of GDP, while predicting that the UK would see somewhere between 1.31% and 4.21% loss of GDP in optimistic and pessimistic scenarios, respectively (Emerson et al. 2017, cited in Belke & Gros 2017). Even the most optimistic prediction of this range being realized would be akin to the damage caused by an economic recession. The most pessimistic scenario at 4.21% forecasted a GDP decline roughly equal to two-thirds of the damage caused to the UK by the 2008 Great Recession, which caused a little over a 6% decline in UK GDP (Office for National Statistics 2018).

Looking back at the economic performance of the UK over the past few years, the catastrophic economic damage forecasted before Brexit occurred never materialized. However, there certainly was economic harm done. While Brexit wasn’t awful for the UK, it has resulted in several economic consequences. One of the biggest effects was, perhaps unsurprisingly, a dramatic decline in trade. Brexit reduced UK-EU trade by around an average of 10.5%, despite the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement being in place. The data also suggests that due to the UK’s departure, some of the trade they would have been receiving has now been redirected to remaining EU member states instead (Buigut & Kapar 2023), a trade diversion effect. Additionally, as seen in Figure 2, UK GDP growth has stagnated. UK GDP dropped precipitously following Brexit’s implementation, recovering to pre-Brexit levels by around the start of 2022. However, growth has not increased since then, and the UK economy has continued to languish, seeing significantly stifled growth since implementation of the Brexit decision (Office for National Statistics 2024).

Brexit is a good example of what sorts of economic benefits countries gain from being members of a PTA, and what sort of economic damage they can expect if they were to leave one as highly integrated as the EU. Striking it out on their own has essentially only caused harm to the UK economy. It additionally has necessitated them to seek out new free trade agreements with both the European Union and new third parties in an attempt to find new international markets to trade with. There are enormously consequential benefits to freer trade, and the simple reality is that the UK has given up a lot of extra money and economic growth by leaving the EU. Whether the increased political control they now possess as a result was worth the cost to British citizens has yet to be seen.

Conclusion

PTAs are a powerful tool that can be used by states to craft trade policy in a way that is beneficial for their respective countries. This chapter emphasized the importance of both political and economic benefits that are created, and furthermore boosted by PTAs. Politically, PTAs enable states to divert trade to themselves or their political/ideological allies or use these agreements to reroute trade in a region, isolating rival states. Economically, trade-creating PTAs boost national welfare, GDP, and trade volume for the members of the agreement, while trade-diverting PTAs also may achieve these outcomes for the members, at the expense of non-member states. PTAs also provide room for countries to negotiate outside of the international trade system, avoiding the most-favored nation principle at the WTO. Despite this function, they are still important for understanding global trade flows. We also examined three case studies, the European Union, NAFTA/USMCA, and Brexit. Both the NAFTA and USMCA agreements were a mutually beneficial win for North American farmers, workers, ranchers, and businesses, as well as tremendous stimulation of the North American economy. The European Union bolstered trade creation in Europe through the implementation of a heavily integrated PTA that continues to influence economic and political policies in Europe. Brexit demonstrated the economic welfare costs associated with leaving a highly integrated PTA. With their development into a position of prominence, PTAs set a new stage for global trade.

Bibliography

Ahearn, Raymond. 2011. “CRS Report for Congress Europe’s Preferential Trade Agreements: Status, Content, and Implications.” https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R41143.pdf.

Belke, Ansgar, and Daniel Gros. 2017. “The Economic Impact of Brexit: Evidence from Modelling Free Trade Agreements.” Atlantic Economic Journal 45 (3): 317–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11293-017-9553-7.

Blenkinsop, Philip. 2023. “At WTO, Growing Disregard for Trade Rules Shows World Is Fragmenting.” Reuters, October 2, 2023, sec. Business. https://www.reuters.com/business/wto-growing-disregard-trade-rules-shows-world-is-fragmenting-2023-10-02/.

Buigut, Steven, and Burcu Kapar. 2023. “How Did Brexit Impact EU Trade? Evidence from Real Data.” The World Economy 46 (6). https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13419.

Carrère, Cèline. 2006. “Revisiting the Effects of Regional Trade Agreements on Trade Flows with Proper Specification of the Gravity Model.” European Economic Review 50 (2): 223–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2004.06.001.

Chow, Daniel. 2016. “How the United States Uses the Trans-Pacific Partnership to Contain China in International Trade | Chicago Journal of International Law.” Cjil.uchicago.edu. December 1, 2016. https://cjil.uchicago.edu/print-archive/how-united-states-uses-trans-pacific-partnership-contain-china-international-trade.

Clausing, Kimberly A. 2001. “Trade Creation and Trade Diversion in the Canada – United States Free Trade Agreement.” The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue Canadienne D’Economique 34 (3): 677–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3131890.

Dadush, Uri, and Enzo Prost. 2022. “The Problem with Preferential Trade Agreements.” Bruegel | the Brussels-Based Economic Think Tank. Bruegel. February 21, 2022. https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/problem-preferential-trade-agreements.

European Commission. 2022. “Schengen Area.” Home-Affairs.ec.europa.eu. European Commission. 2022. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/schengen-area_en.

———. 2023. “ Value of EU Trade Deals Surpasses €2 Trillion.” European Commission. November 15, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_5742.

Ghosh, Sucharita, and Steven Yamarik. 2004. “Are Regional Trading Arrangements Trade Creating?” Journal of International Economics 63 (2): 369–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-1996(03)00058-8.

Hayes, Adam. 2023. “Brexit Meaning and Impact: The Truth about the U.K. Leaving the EU.” Investopedia. June 29, 2023. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/brexit.asp.

Krueger, Anne. 1999. “Trade Creation and Trade Diversion under NAFTA.” National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w7429.

Luo, Chih-Mei. 2017. “Brexit and Its Implications for European Integration.” European Review 25 (4): 519–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1062798717000308.

Magee, Christopher S.P. 2008. “New Measures of Trade Creation and Trade Diversion.” Journal of International Economics 75 (2): 349–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2008.03.006.

Mance, Henry. 2016. “Osborne Warns of 10%-18% Hit on House Prices from Brexit.” Financial Times. May 20, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/5e560a76-1ea6-11e6-b286-cddde55ca122.

National Archives. 2021. “Marshall Plan (1948).” National Archives. September 28, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/marshall-plan.

Office for National Statistics. 2018. “The 2008 Recession 10 Years On.” Ons.gov.uk. April 30, 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/articles/the2008recession10yearson/2018-04-30.

———. 2024. “GDP Monthly Estimate, UK: February 2024.” Www.ons.gov.uk. April 12, 2024. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/grossdomesticproductgdp/bulletins/gdpmonthlyestimateuk/february2024.

Office of the United States Trade Representative. 2020. “United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement.” Ustr.gov. 2020. https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement.

Romalis, John. 2007. “NAFTA’s and CUSFTA’s Impact on International Trade.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 89 (3): 416–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40043039.

Trefler, Daniel. 2004. “The Long and Short of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement.” The American Economic Review 94 (4): 870–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3592797.

United Nations. 2023. “Key Statistics and Trends in Trade Policy 2022.” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. March 17, 2023. https://unctad.org/publication/key-statistics-and-trends-trade-policy-2022.

Villarreal, Angeles, and Ian Fergusson. 2020. “NAFTA and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).” Congressional Research Service. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20200302_R44981_cb2c8918ab5d623c4954e666604915302585b487.pdf.

World Trade Organization. 2011. “The WTO and Preferential Trade Agreements: From Co-Existence to Coherence, World Trade Report.” https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/anrep_e/world_trade_report11_e.pdf.

Yao, Xing, Yongzhong Zhang, Rizwana Yasmeen, and Zhen Cai. 2021. “The Impact of Preferential Trade Agreements on Bilateral Trade: A Structural Gravity Model Analysis.” Edited by Bernhard Reinsberg. PLOS ONE 16 (3): e0249118. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249118.

Zaken, Ministerie van Buitenlandse. 2021. “EU, EEA, EFTA and Schengen Countries | Netherlands Worldwide.” Www.netherlandsworldwide.nl. October 22, 2021. https://www.netherlandsworldwide.nl/eu-eea-efta-schengen-countries.