7 Production: Domestic Interests and Institutions

FDI Politicization: The History

The politics of foreign direct investment (FDI) and the battle between domestic institutions and multinational corporations (MNCs) is a storied history that, at its core, is the cornerstone of the relationship between states and the firms they seek to regulate. It’s a delicate balance between the founding principle of states to maximize their own wellbeing in their natural jurisdiction and MNCs goals of maximizing the well-being of their stakeholders (Vernon 1998). It is this intrinsic conflict that motivates the ever-shifting winds of FDI regulatory policy.

The history of FDI politicization has gone through many iterations of increased restrictions, open liberalization, and relative stagnation since its inception. Various scholars note the relative novelty of the concept of foreign investment regulation following the industrial revolution. Prior to that, capital flows generally went from rich Western European countries to the forced cash-poor lands they had subjugated to their rule. When states did have the autonomy to regulate FDI they rarely did so, as such investment often came in the form of large-scale infrastructure projects (Vernon 1998). However, as the world entered the twentieth century, the approach towards FDI policy began to change.

By the early 1900s, private firms began to direct investments towards research and development and other projects based on intellectual property. These investments lead to the development of firm-specific assets or assets exclusive to a firm for private use. Additionally, firms saw an increase in market demand for consumer products, not just domestically but internationally. Together, this led to an increase in FDI to produce goods and services, allowing firms to create economies of scale through intellectual properties (Danzman 2020). The increase in FDI paved the way for the global economy, but with it came the first instances of politicization that would linger for years.

FDI faced intense politicization during the Interwar period, the time between the first and second World Wars. Cases of isolationist behavior arose from the perceived threat to national security posed by foreign ownership of production assets. One example of this was the seizure of all foreign-based assets by the U.S. government during WWI, the likes of which included chemical and pharmaceutical patents owned by U.S. subsidiaries of German companies. Simultaneously, the removal of foreign-based firms helped advance the interests of local producers who could finally compete with the larger, more productive MNCs (Pandya 2013).

These regulatory actions brought about changes to the organization of political and labor efforts that solidified the position of the U.S. in terms of deflecting foreign investment. Political coalitions created by state-led development strategies dissolved the resistance of firms operating domestically under foreign control while local firms benefited from high tariff rates. Workers gained higher wages in protected industries where labor was organized effectively. Through this, politicians and bureaucratic agents who helped shape FDI policy reaped the benefits from their regulatory decisions (Danzman 2020).

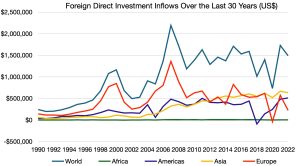

Towards the end of the twentieth century, countries markedly adopted an increasingly open stance towards FDI. During the 1970s, up to 35 percent of industries within a given country were protected from foreign ownership of local firms; thirty years later, that number had dropped to 10 percent. Additionally, MNCs faced more favorable attitudes from host countries. For example, beginning in 1975, over eighty acts of expropriation were directed at MNCs, levied across thirty countries internationally. Expropriations are actions taken by host countries that seek to redistribute income generated by MNCs to domestic groups through the use of tax increases and sometimes seizure of property. Nearly a decade later, not only were these acts becoming increasingly rare, but many governments revised national investment laws to specifically guarantee property rights for foreign-owned MNCs (Pandya 2013).

FDI Liberalizing Factors

Foreign Direct Investment can directly and indirectly benefit host countries by aiding in capital formation, encouraging economic growth, and increasing market access. The arrival of MNCs can also expand the market of domestic firms if they stand to benefit from vertical economic integration (if they become suppliers to MNC production). When domestic governments enact liberalizing policies regarding FDI, they can benefit from the economic advantages of expanded markets. FDI policy liberalization can only be achieved through effective collective action engagement among governments, domestic institutions, and interest groups; democratic systems are best suited to facilitate the requisite collective actions necessary for liberalization.

As countries move towards greater democratization and economic growth in the developing world, they trend towards higher levels of FDI liberalization and shift away from protectionism (Pandya 2014). Shifting towards a reduction of ownership and operational restrictions is an indicator of a nation adopting more liberal attitudes towards FDI. Democratic states have an inherent obligation to serve their constituents and are motivated by a desire to remain in office once elected. Political action on the part of motivated representatives that can claim credit for the arrival of MNCs and the accompanying economic growth tend to cause these shifts. As states become increasingly democratized, they encourage even more FDI due to increases in the provision of public goods and the implementation of more attractive property rights policy. It has been found that public opinion of FDI improves as education increases, which carries the implication that higher skilled labor enjoys higher wages and other benefits from increased FDI (Pandya 2010). This is of benefit to representatives who are looking for the introduction of more FDIs and for reelection.

Autocratic states, on the other hand, face a far greater challenge in attracting FDI. For starters, autocrats have fewer checks on their power and for this reason cannot make credible commitments to foreign investors on the same level democratic governments with greater institutional checks and balances can (Gordon 2009). Autocratic governments present higher levels of political risk to firms considering FDI in their nation as a symptom of their lack of credible commitment (Gordon 2009). These risks include a higher likelihood of war and political violence including terrorism, expropriation, which is the seizure of a firm’s property by the host nation government, and denial of government permits (Gordon 2009). Autocratic governments also present the problem of the Obsolescing Bargain Theory to MNCs. Obsolescing bargain theory is the idea that MNCs have great bargaining power when deciding where to put investments, but their bargaining power disappears once they have selected a site and have incurred sunk costs, or invested money or material goods into a site which they have no hope of recouping unless the investment becomes profitable to them in some way. Once this has occurred, host states gain leverage and the ability to alter the terms of the original agreement. This is more likely to arise with changes in government preference or as benefits of expropriation grow (Wells 1998).

Financial Mechanisms

Just as domestic interests and institutions affect policies and regulations, they also regulate FDI openness and closure using financial mechanisms. Domestic political institutions have access to financial powers that allow them to make decisions for credit distribution through personal and political networks instead of market discipline (Danzman 2020). For example, when there is banking reform that limits locals’ privileged access, elites will seek alternative sources of finance. MNCs can provide greater access to international finance, and the lack of access to financial privileges may drive domestic businesses to support policies and lobby to support FDI liberalization (Danzman 2020). Costly financing constraints force local firms to support liberal FDI policies in order to benefit from MNCs’ capital. Financial constraints faced by domestic firms can encourage FDI openness to gain increased access to MNCs’ investment financing and increase economic growth by benefiting domestic economies (Danzman 2020).

Governments can also use financial instruments to attract FDI by implementing fiscal and financial policy incentives. Financial incentives can appeal to MNCs to engage in operations by helping reduce the cost of establishment and operation (Nye 1974). Financial incentives can be indirect or direct subsidies, including loans, subsidies, grants, expatriation costs, and others (Cuervo-Cazurra, Silva-Rêgo, and Figueira 2022). The government supplies direct subsidies to assist the MNC by renting operation areas, funding job training, and covering other operations costs for greenfield projects (Cuervo-Cazurra, Silva-Rêgo, and Figueira 2022). Funding can also be provided to build infrastructure such as: power, roads, healthcare, and education facilities (Cuervo-Cazurra, Silva-Rêgo, and Figueira 2022). Comparatively, fiscal incentives involve preferential tax treatment through deductions, exemptions, grants, or other strategies. It comprises tax allowances, tax holidays, lower tax rates, credits, allowances, and decreased import tariffs (Gilpin 1975). Unlike financial incentives, fiscal incentives are more beneficial to FDI in the latter phases of investment as they help decrease future operation costs for the MNC (Cuervo-Cazurra, Silva-Rêgo, and Figueira 2022).

Financial mechanisms can also be used to restrict FDI. One of the most common methods of engaging in FDI is mergers and acquisitions (M&A), when two companies join together to form one company or when one company takes over another. The government’s response towards M&As is usually driven by competition or the “nationality” of the MNC involved in the M&A (Lindblom 1977). Economic Nationalism is the partiality for domestics instead of foreigners in economic interests. The level of economic nationalism within a country determines the extent domestic institutions support or oppose FDI. Governments advocate for firms not to be owned by foreign corporations and instead remain domestically owned (Dinc and Erel 2013). Nationalist governments are able to achieve economic nationalism by intervening in economic activities, promoting and implementing policies that would be in favor of domestic corporations. Some of the common methods used to heighten nationalism in M&As are moral persuasion, public interests, creating a national champion, and providing financing to domestic bidders (Dinc and Erel 2013).

Moral persuasion can be used by a government to initially block the merger and utilizing implicit threats against the MNC (Dinc and Erel 2013). Governments can impose restrictions to safeguard public interests (Dinc and Erel 2013). National champions, which are large companies with vital roles in a country’s economy, are created to promote the interests of a political group to prevent M&A. This can be achieved by aiding the mergers of domestic firms and making them far more difficult to be acquired by foreign companies (Dinc and Erel 2013). A domestic firm can grow too large to feasibly be acquired by an MNC, discouraging FDI. Governments can also buy time to obtain or finance a domestic bidder by implementing prudential rules or creating requirements for regulatory approvals from different commissions (Dinc and Erel 2013). A “white knight” or a favorable acquirer in order to obstruct MNCs from acquiring the firm can be used (Dinc and Erel 2013). The “white knight” may receive financing from financial institutions that the government backs. Another strategy for implementing nationalism to block FDI is using golden shares, which are shares that grant veto power to shareholders over changes in the company’s operation, rules, and regulations. Having golden shares in a company allows governments to make the decision for the company not to be acquired (Dinc and Erel 2013). Similar to these techniques, domestic institutions can implement many other policies to discourage MNCs from engaging in FDI.

Regulation of FDI

One of the more difficult aspects of studying FDI is the complexity of enforcement and regulation mechanisms that govern FDI policy around the globe. Due to the expansive nature of multinational participation and various regulatory issues (i.e., business licensing, finance, labor, etc.), no single international regulatory agency strictly handles FDI policy. For this reason, the regulatory environment in which FDI policy exists is often confusing, complex, and, at times, contradictory. One concern for scholars on the subject is the differences in the location of regulatory authority over FDI within governments.

By and large, investment policy is often created by the government’s legislative body, which gives a government the authority to regulate the industry as a whole, and enforcement is usually delegated to the bureaucracy via regulatory agencies. One example is an investment board, which is a regulatory body designed to review and approve foreign investment schemes and additionally provide guidance on entry and operational procedures for MNCs. Other nations may vest regulatory authority in preexisting independent agencies due to their long-term involvement in FDI regulation. An example of such is Japan’s Ministry of Trade and Industry, which coordinates FDI regulation with other macroeconomic policy points (Danzman 2020).

In the United States, the interagency committee that is responsible for reviewing and approving foreign investment in domestic companies is called the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). While CFIUS is not considered an investment board or an independent agency, it was established by an executive order in 1975, and its jurisdiction and authority have been expanded over the years by subsequent legislation and executive orders. CFIUSs primary mandate is to review and evaluate proposed foreign investments in U.S. businesses to determine whether they could be a threat to U.S. national security, a constant concern since the Interwar period. CFIUS has the power to block or modify proposed foreign investments in U.S. companies, as well as impose conditions on those investments to mitigate any potential national security risks. Its governing committee, composed of representatives from various government agencies collectively operating under the Department of the Treasury, makes decisions that are confidential, generally do not disclose the details of their reviews or investigations (Jackson 2020).

The Political Power of MNCs

While some scholars have chosen to study the various government institutions around the world and the mechanisms they use to administer and govern FDI regulation, others have chosen to analyze multinational corporations (MNCs) as political actors playing a significant role in shaping the global economy. For example, in the United States, MNCs represent less than 1% of American firms but comprise more than 24% of private sector GDP and 26% of private sector compensation (Ballor and Yildirim 2020). Similarly, the OECD estimates that MNCs constitute half of global exports, almost a third of world GDP (28%), and nearly a fourth of global employment. Their transnational activities are usually one of two types: outsourcing, where a company hires an external party to perform services or create goods traditionally performed in-house, and offshoring, moving a business process or operation from one country to another to capitalize on lower costs of operation (Sako 2005). They have driven the transformation of international trade, investment, and technology transfers in the globalized economy. The implications are massive for various policy issues including taxation, investment protection, and immigration across different political and economic institutions. For this reason, scholars have assessed how and why MNCs function as political actors.

Researchers have identified unique economic and political characteristics in multinational corporations that distinguish them from domestic firms and enable them to influence policy preferences significantly. The most productive MNCs are characterized by their large size, extensive production capacities, and deep integration into global value chains (Danzman 2020). Their size and international presence allow them to exert influence directly through lobbying and respond strategically to international regulations, often shaping them to fit their needs (Kim and Milner 2021). Additionally, the complex and overlapping regulatory regimes in global trade governance present challenges and opportunities for MNCs, which they navigate through their sophisticated corporate strategies (Sako 2005).

In contrast, the least productive firms invest in only the most productive locations (Pandya 2013). Another distinct characteristic of MNCs that allows them to shape policy preferences is their influence on foreign policy. Because of their size and scope, MNCs greatly influence trade, foreign investment, exchange rates, and immigration. Regarding trade, it has long been understood that firms have different preferences based on their ties to the international economy. Furthermore, domestic firms competing with imports will advocate for more excellent protection, whereas big exporters and MNCs will opt for freer trade (Vernon 1998). Finally, MNCs mainly advocate preferential trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties (Danzman 2020). They have been the primary leaders in including provisions protecting investment and intellectual property rights and liberalizing services in preferential trade agreements to gain an edge over MNCs from other countries, which are excluded from the agreements (Pandya 2013).

All in all, these policy preferences and distinct characteristics lead MNCs to exert their political influence in three primary ways: direct lobbying, indirect influence as a component of the state, and unintended influence as an agenda-setter. First, MNCs may directly engage in political activities such as lobbying and contributing to campaigns to affect the policy-making process or to pressure political leaders to address their demands. In doing so, they can partner with industry associations and political action committees to advance similar interests. Firms can leverage their bargaining power by offering both “inducements” or promises of brand-new investment and “deprivations” or threats of withdrawal of investment (Vernon 1998). Second, many have argued that MNCs hold an inadvertent role in foreign policy as a component of the state (Danzman 2020). In this point of view, governments have utilized MNCs to further their national interest by bolstering the effects of sanctions through the production networks of MNCs, fostering capital transfers through firms to enhance monetary policy, or permitting MNCs’ foreign affiliates to assist in gathering intelligence (Nye 1974). Finally, MNCs can hold extensive agenda-setting power from their simple presence abroad. The view of governments towards MNCs is that of a “privileged position” that assists political leaders in defining problems, devising policies, and prioritizing objectives (Pandya 2013). Taken together, multinational corporations exert significant influence over domestic institutions through various methods that ultimately work to advance their interests on a global economic level (Jackson 2020).

Case Study: Ireland and the Celtic Tiger

The relationship between domestic institutions, multinational corporations, and foreign direct investment is complex and interconnected. Ireland during the Celtic Tiger period is an intriguing historical example of this multifaceted relationship. From the 1990s to the early 2000s, Ireland witnessed unparalleled economic growth, largely thanks to foreign direct investment, which saw multinational corporations establish operations in Ireland and create jobs for local workers (Vernon 1998). This success did not appear suddenly, rather, it was a series of policy changes that arose over multiple decades. Understanding the causes of Ireland’s economic success during the Celtic Tiger period can provide useful insights into the relationship between domestic institutions, MNCs, FDI, and influence discussions on promoting economic growth and development in other countries.

In the 1920s, Ireland held a staunchly protectionist stance to protect local industries and promote a self-sufficient economy (Danzman 2020). However, this counterproductive policy led to high unemployment rates and mass emigration (Coulter and Coleman 2003). Like other protectionist countries, the Irish government gradually realized the opportunities that came with allowing foreign direct investment in the 1960s, and as a result, began dismantling their trade barriers to draw in foreign investors (Pandya 2013). This led to an inflow of FDI into the country, prompting Ireland’s explosive economic growth in the 1990s (Coulter and Coleman 2003). In 1994, one of the most rapid years of growth, Irish Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rates increased to 5.8% (Coulter and Coleman 2003). Despite the benefits of FDI, managing tensions between domestic institutions and multinational corporations remained a persistent challenge. Critics argued that the Irish government had prioritized the interests of foreign corporations over those of local businesses and workers (Jackson 2020). Allegedly, some MNCs were not paying their fair share of taxes or underpaying their workers (Barry, Barry, and Menton 2016). Others were concerned about the effect of FDI on Ireland’s society and culture. The influx of foreign corporations caused property prices and rent inflation, making it difficult for locals to afford housing and widening the social gap (Coulter and Coleman 2003). Nonetheless, Ireland’s strategic location in the European Union, well-educated workforce, and English-speaking population made it an enticing place for multinational corporations looking to enter the European market (Henderson 2008). The government continued developing policies favorable to FDI, such as low corporate tax rates, strengthening the country’s appeal to multinationals (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) n.d.).

Ireland’s increasing dependence on MNCs for economic growth led to concerns about the impact of foreign investment on local businesses and workers (Henderson 2008). The government addressed these concerns by implementing policies promoting local entrepreneurship and investment alongside FDI (Bernard, Jensen, and Schott 2009). By establishing Enterprise Ireland, a state agency tasked with promoting the development of Irish-owned businesses an attempt was made to support and fund Irish businesses to help them compete with the more resource-rich multinationals (Autor et al. 2020). In addition to promoting local entrepreneurship, the Irish government invested in education and training programs to help local workers acquire the skills to compete in the global economy (Barry and Bradley 2013). This investment into human capital ensured that Irish employees benefited from jobs created by the foreign firms operating in Ireland. While there were many, one example of this program was Skillnets, which funded training programs for the workers of small and medium-sized corporations (Yeaple 2009). Despite these efforts to balance the competing interests of foreign investment, domestic businesses, and industries some expressed concerns about the longevity and fairness of the tax incentives afforded to multinational corporations (O’Rourke and Alan 2010). Low corporate tax rates did enable foreign investment and economic growth. Still, concerned parties believed this could lead to a “race to the bottom,” with countries competing to provide corporations with the most favorable tax environment (Barry and Bradley 2013). The 2008 global financial crisis significantly impacted Ireland’s economy, leading to a period of instability and slowed growth. Some critics suggested that the country’s reliance on FDI had left it vulnerable to economic shocks, as foreign corporations chose to relocate or downsize operations in response to the shaky economic conditions (Forfas, 2010). The Irish government introduced various measures to promote local businesses and industries, including a 500-million-euro innovation fund for high-growth startups (“Project Ireland 2040 National Development Plan 2018—2027” 2018).

One critical lesson from Ireland’s experience is the need to develop a comprehensive strategy for promoting FDI while supporting local businesses and industries (Henderson 2008). In particular, governments must ensure they are not sacrificing long-term economic growth for short-term gains by offering excessive tax incentives to foreign corporations (O’Rourke and Alan 2010). Moreover, they must ensure that MNCs do their part to support local communities and create high-quality jobs (O’Rourke and Alan 2010). Additionally, governments must invest in education and training programs to help local workers acquire the skills to compete in the global economy (Hunt and Wheeler 2017).

Ireland’s experience during the Celtic Tiger period illustrates the complexities of FDI and the tensions that can arise between domestic institutions and MNCs (Henderson 2008). While the government’s decision to liberalize the economy to foreign investment played a crucial role in stimulating economic growth, it also created challenges that policymakers must navigate carefully (Lavelle and Kenny 2016).

Conclusion

Domestic institutions exert significant political influence when it comes to regulating foreign direct investment. Since the twentieth century, foreign direct investment has been used to expand industry while the world engages in repeated cycles of increasing and decreasing levels of trade liberalization. The measures taken by each country to regulate foreign direct investment changes based on regime type and domestic politics, but in cases such as the United States, where organized interests play a powerful role in legislative and oversight processes, multinational corporations occupy an influential role in dictating FDI policy for the nation. Various factors contribute to domestic Institutions and interest groups creating policies that liberalize FDI, including democratization, increased effect on economic growth, shift towards neoliberal reform, increased cost of closure, trade openness, and reaction to other economic policies. Financial mechanisms are also used to regulate FDI closure and openness. Governments use fiscal and financial incentives to attract FDI. Moreover, financial constraints faced by domestic firms can influence FDI liberalization. On the other hand, governments can use moral persuasion, public interests, prudential rules for financial companies, golden shares in privatized companies, providing financing to domestic bidders, playing for time, and creating national champions to restrict FDI. The case study uses the example of Ireland’s Celtic Tiger period to discuss the complex relationship between domestic institutions, multinational corporations (MNCs), and foreign direct investment (FDI). The policy changes made by the Irish government over multiple decades to attract FDI led to explosive economic growth but also raised concerns about the impact of foreign investment on local businesses and workers. The government addressed these concerns by implementing policies to promote local entrepreneurship and investment alongside FDI. One of the critical lessons learned is the need to develop a comprehensive strategy for promoting FDI while supporting local businesses and industries, investing in education and training programs, and ensuring MNCs create high-quality jobs and support local communities.

Bibliography

“About Enterprise Ireland.” 2022. Enterprise Ireland. 2022. https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/about-enterprise-ireland.

“About Us.” n.d. Skillnet Ireland. Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.skillnetireland.ie/about-us.

“Activities of U.S. Multinational Enterprises: 2016 | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).” n.d. Accessed April 22, 2024. https://www.bea.gov/news/2018/activities-us-multinational-enterprises-2016.

Autor, David, David Dorn, Lawrence F Katz, Christina Patterson, and John Van Reenen. 2020. “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2): 645–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa004.

Baccini, Leonardo. 2019. “The Economics and Politics of Preferential Trade Agreements.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (1): 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070708.

Ballor, Grace A., and Aydin B. Yildirim. 2020. “Multinational Corporations and the Politics of International Trade in Multidisciplinary Perspective.” Business and Politics 22 (4): 573–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2020.14.

*Barry, Frank, and John Bradley. “Economic imperialism and the tyranny of experts: Ireland in the crucible of the international financial crisis.” Journal of Contemporary European Research 9, no. 4 (2013): 560-579.

*Barry, Frank, and John Bradley. FDI and the labour market: Lessons from Ireland’s inward investment experience. Oxford University Press (2013).

Barry, Frank, Linda Barry, and Aisling Menton. 2016. “Tariff‐jumping Foreign Direct Investment in Protectionist Era Ireland.” The Economic History Review 69 (4): 1285–1308. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12329.

Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, and Peter K. Schott. 2009. “Importers, Exporters and Multinationals: A Portrait of Firms in the U.S. That Trade Goods.” In Producer Dynamics: New Evidence from Micro Data, 513–52. University of Chicago Press. https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/producer-dynamics-new-evidence-micro-data/importers-exporters-and-multinationals-portrait-firms-us-trade-goods.

Coulter, Colin, and Steve Coleman, eds. 2003. The End of Irish History?: Reflections on the Celtic Tiger. Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9780719062308.

Cuervo-Cazurra, Alvaro, Bernardo Silva-Rêgo, and Ariane Figueira. 2022. “Financial and Fiscal Incentives and Inward Foreign Direct Investment: When Quality Institutions Substitute Incentives.” Journal of International Business Policy 5 (4): 417–43. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-021-00130-9.

Danzman, Sarah Bauerle. 2020. Merging Interests: When Domestic Firms Shape FDI Policy. Business and Public Policy. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/us/universitypress/subjects/politics-international-relations/political-economy/merging-interests-when-domestic-firms-shape-fdi-policy?format=HB&isbn=9781108494144.

Dinc, I. Serdar, and Isil Erel. 2013. “Economic Nationalism in Mergers and Acquisitions.” The Journal of Finance 68 (6): 2471–2514.

Erel, Isil, Yeejin Jang, and Michael Weisbach. 2020. “The Corporate Finance of Multinational Firms.” w26762. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26762.

“Foreign Direct Investment: Inward and Outward Flows and Stock, Annual.” n.d. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.FdiFlowsStock.

*Forfas. “FDI in Ireland: Performance and policy.” (2010).

Gilpin, Robert. 1975. U.S. Power and the Multinational Corporation: The Political Economy of Foreign Direct Investment. New York: Basic Books. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000021706.

Gordon, Kathryn. 2009. “Investment Guarantees and Political Risk Insurance: Institutions, Incentives and Development.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1718484.

*Henderson, David. “The Celtic Tiger and its lessons for globalization.” Journal of International Affairs 61, no. 2 (2008): 59-76.

*Hunt, Jennifer, and Andrea L. Wheeler. “Foreign direct investment in Ireland: policy implications for emerging economies.” Journal of International Business and Economy 18, no. 1 (2017): 31-44.

Jackson, James. 2020. “The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS.” RL33388. Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33388/91.

Kim, In Song, and Helen Milner. 2021. “Multinational Corporations and Their Influence through Lobbying on Foreign Policy.” In Global Goliaths: Multinational Corporations in the 21st Century Economy, 497–536. Brookings Institution Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7864/j.ctv11hpt7b.

Kim, In Song, and Iain Osgood. 2019. “Firms in Trade and Trade Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 22 (Volume 22, 2019): 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-063728.

Kim, Soo Yeon. 2015. “Deep Integration and Regional Trade Agreements.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Political Economy of International Trade, edited by Lisa L. Martin, 0. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199981755.013.25.

Kobrin, Stephen. 2005. “The Determinants of 67 Liberalization of FDI Policy in Developing Countries: A Cross-Sectional Analysis, 1992-2001.” Transnational Corporations 14 (1): 67–104.

*Lavelle, John and Kenny, O. “Irish entrepreneurship policy: Progress made and lessons learned.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 20 (2016): 223-244.

Lindblom, Charles Edward. 1977. Politics And Markets: The World’s Political-Economic Systems. Basic Books. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Politics_And_Markets/9cuob2wEsYcC?hl=en.

“Multinational Enterprises in the Global Economy: Heavily Debated but Hardly Measured.” 2018. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/industry/ind/MNEs-in-the-global-economy-policy-note.pdf.

Nye, Joseph S. 1974. “Multinational Corporations in World Politics.” Foreign Affairs 53 (1): 153. https://doi.org/10.2307/20039497.

*O’Rourke, Kevin H., and Alan M. Walsh. “The Irish economy since 1987: from crisis to boom to bust.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24, no. 3 (2010): 67-85.

Pandya, Sonal S. 2010. “Labor Markets and the Demand for Foreign Direct Investment.” International Organization 64 (3): 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818310000160.

———. 2013. Trading Spaces: Foreign Direct Investment Regulation, 1970–2000. Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139628884.

———. 2014. “Democratization and Foreign Direct Investment Liberalization, 1970-2000.” International Studies Quarterly 58 (3): 475–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12125.

“Project Ireland 2040 National Development Plan 2018—2027.” 2018. Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform. https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/37937/12baa8fe0dcb43a78122fb316dc51277.pdf#page=null.

Ruane, Frances, and Peter J. Buckley. 2006. “Foreign Direct Investment in Ireland: Policy Implications for Emerging Economies.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.922277.

Sako, Mari. 2005. “Outsourcing and Offshoring: Key Trends and Issues.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1463480.

Vernon, Raymond. 1998. In the Hurricane’s Eye: The Troubled Prospects of Multinational Enterprises. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1smjs9p.

Wells, Louis T. 1998. “God and Fair Competition: Does the Foreign Direct Investor Face Still Other Risks in Emerging Markets?” In Managing International Political Risk, edited by Theodore H. Moran, 15–43. Malden, Mass: Blackwell.

Yeaple, Stephen Ross. 2009. “Firm Heterogeneity and the Structure of U.S. Multinational Activity.” Journal of International Economics 78 (2): 206–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.03.002.