8 Production: International Institutions

Introduction

Investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) is the process by which multinational corporations (MNCs) engage in legal disputes with state actors. To invest in foreign states, both parties must sign an international investment agreement (IIA). If this contract is broken, the parties agree to go to arbitration. Arbitration is used as a way to solve legal disputes impartially, and the format of arbitration is dependent on the IIA, much like the United States regulated judicial system and due process. However, international dispute resolution is far more complex than national judicial systems due to a lack of a common constitution or shared legal document that can be applied on a global level. As such, the source of law for each case depends on the specific agreements between the state and foreign investors.

International investment treaties were created to establish a standard for the treatment of foreign investors by host countries. If an international investment treaty is breached, the involved parties can bring their grievances to a courtroom. This is the process of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), which allows private investors and states to resolve legal disputes through arbitration. ISDS aims to resolve trade conflicts between host states and multinational corporations peacefully. ISDS permits international investors to resolve differences with the government of a host state in which their investment was made in a neutral venue through a binding international tribunal. Without ISDS, foreign investors would have to rely on local or state courts in the host country to resolve conflicts. Investors would face obstacles such as a lack of legal safeguards and judicial independence because courts would make biased decisions in favor of the host country. Courts that handle ISDS claims are responsible for awarding remedies to the violated party, usually a financial award (USTR, 2014). Most ISDS claims are initiated by private investors in developed countries.

Bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) are both part of the process of dispute resolution. BITs, a type of IIA, ensure that foreign investors in a different country receive fair treatment in regard to private investments they make in a host country (Cornell, 1992). The ICSID is an organization that assists in the moderation of the arbitration process, and it is specifically designed for international disputes. ICSID and BITs provide standards and mechanisms for ISDS procedure. ISDS is critical for MNCs as it provides a fair and legal method of settling disputes. By setting the individual terms for dispute settlement in the investment agreement, states can choose what kinds of protection they offer investors. ISDS allows them to oversee foreign investors’ grievances in a fair light and builds on the legal system created domestically, encouraging continuity when settling disputes.

Further, the ISDS process is extremely important for international relations. Prior to the start of the more formalized ISDS process, foreign investors engaged in legal disputes with the host country under the host’s courts and laws. Foreign investors were treated the same as domestic corporations, and the investors were not offered the same protection that they might have in their home state. These investor-state disputes could then spread in state disputes, leading to increased politicization and risk of further conflict. Because of this potential consequence, there arose a need for disputes to be handled that would offer protections to investors in host states.

In this chapter, we’ll be discussing how ISDS addresses the problem of legal disputes between state actors and foreign investors. We will review historical background and trends, look at a real-world example, and compare ISDS claims to how the World Trade Organization settles disputes. In observing the accomplishments of ISDS, we will examine notable criticisms of the process and the relation to multinational companies.

Design Features and Trends

Historical Background

Before ICSID, various governments made attempts to create a system to encourage and protect foreign direct investments. This was difficult given the variety of views and biases governments had on how to handle international legal issues, including who would be best to arbitrate such issues and who would be financially responsible when conflict such as this arose. ICSID was created in 1966 via what is colloquially known as the Washington Convention. Available online, the historical record describes the aim of the organization “to promote the resolution of disputes” through “facilitating recourse to international conciliation and arbitration” (ICSID, n.d.). As a member of the World Bank Group, ICSID was created as part of an international financial institution, becoming a part of a global infrastructure for developing prosperity, especially in developing nations, and reaching a shared understanding with member states. It is currently ratified by 158 states (ICSID, 2022). ICSID, along with the specific regulations of the international investment agreement signed, determines the mechanisms by which the ISDS process is governed. The most common type of IIA is the bilateral investment treaty (BIT).

Bilateral Investment Treaties

Bilateral investment treaties are agreements that are signed to establish terms and conditions on an international level for private investments between nations and companies of one state in a different state (Cornell, 2022). It is when these terms have been violated that iSDS suits occur. Countries sign BITs for a multitude of reasons. They can sign them to get around weak domestic institutions or to remain competitive on the international market, particularly with other countries who have more foreign investment. They can also sign them to be perceived as open to foreign investors or to raise the costs of expropriation, inevitably making private investor protections more necessary (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010). In most cases, most countries that sign BITs will have high levels of foreign direct investment (FDI). However, the behavior of states can play a bigger role than simply just the act of signing BITs. Some research has shown that BITs follow FDIs, rather than the other way around FDIs (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010). That is, countries who have a high amount of foreign direct investment will then sign more investment treaties. There is a demand by foreign investors to get into markets and proximity to markets in nearby regions (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010).

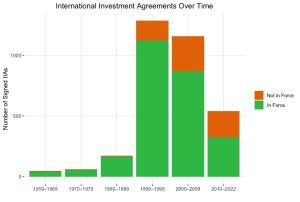

Over 2,000 BITs have been signed. Not all of these treaties are in force, as some have been signed but not enacted. The chart below shows the number of International Investment Agreements per year, of which BITs are a subset. These counts are provided by the UNCTAD 2023 World Investment Report.

There are certain circumstances in which BIT organizers decide to delegate disputes over to the ICSID. This is seen when the private investor’s home country is much more powerful than the host country they were in, or if the home country has a large number of multinational corporations. Also, if the host country participated in expropriation within the last decade or if they receive world bank assistance. Disputes can also be delegated if the host country has been independent from the formal system in the last decade. BITs are different and unique to the countries they are being applied to. This uniqueness means the effects of the treaties will be different depending on the circumstances. The effects of BITs can also be dependent on the behaviors of those signing. Commonly, states that are engaged frequently in international arbitration end up receiving fewer FDIs, which is only amplified if they lose their arbitration dispute.

The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

Like most governmental processes, ISDS requires a bureaucratic system to assist in achieving its purpose. The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is where countries can go for assistance in resolving investor-state disputes (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). It is currently located in Washington, D.C., where it has resided since its inception in 1965. As a member of the World Bank Group, ICSID exists to solve arbitration problems between investors and states (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). As of 2022, 158 states have signed and ratified their membership in the agreement (World Bank Group).

There are four stages to the process of settling these disputes in the ICSID. First, the case is registered with ICSID and a tribunal appointment is made. Next, there is the hearing on the jurisdiction of the case. Subsequently, a second hearing is held on merit which can lead to an awarded amount, and lastly, there can be an annulment processed if it is requested. (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). ICSID cases are most commonly heard by a three-person arbitration panel, whose appointment is dictated by the terms of the investment agreement.

State consent to arbitration is a key design feature in the functions of the ICSID. In international law, there are legal frameworks that cannot be bypassed without states’ consent (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). Bypassing these frameworks ensures that it will not be necessary to exhaust local remedies and other functions done through international law. This simplifies ISDS significantly. Consent can be given through several different methods. It can be given in a government contract, an interstate treaty, or through domestic arbitration law (Alle & Peinhardt, 2010). For ICSID, states give their consent through the signing of the international investment agreement.

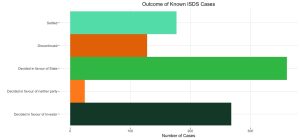

Another critical feature of the ICSID is the process of enforcement. Members need to consent or agree to awarding the correct amount within their domestic courts. This means the court can decide in favor of the state, the investor, the suit can be discontinued, or there can be no damages awarded (UNCTAD, 2021). The following chart shows the outcome of all known ISDS cases, as recorded by the UNCTAD’s ISDS Navigator (UNCTAD 2023).

Whichever direction the case goes, the appropriate party must enforce the court’s decision. In some instances, states may be forced to pay through seizure of their assets in other countries.

Trends in Investor-State Dispute Settlement

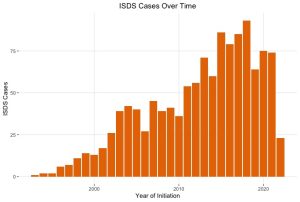

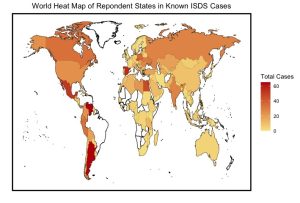

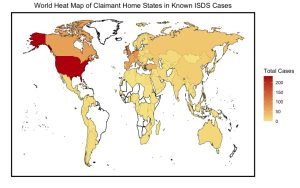

In recent years, the decline in IIAs signed and in ISDS cases per year has sparked questions over the future of the ISDS process. Specifically, scholars have questioned what the benefits of ISDS are for state actors and the effectiveness of IIAs for increasing FDI (Johnson, 2016). Others have criticized the lack of transparency in the process. These criticisms are detailed later in the chapter. The following graphs pull data from UNCTAD’s Investor-State Dispute Navigator, outlining trends in known ISDS cases that may provide insight into the future direction of ISDS.

ISDS vs. WTO Dispute Settlement

To better understand the investor-state dispute settlement procedure, it can be compared to the dispute settlement procedure of the World Trade Organization, shortened as the WTO, which is another important institution in the study of international political economy. These differences extend beyond the surface-level understanding that trade and investment differ. It is important to carefully compare the WTO’s dispute settlement process and the ISDS process given the differences in scope and jurisdiction. One fundamental difference is that while WTO disputes occur between states, ISDS occurs between foreign corporations and states. According to the WTO’s general regulations, foreign corporations are prohibited from suing the state they have business with through the WTO. However, these MNCs can pursue legal action if the investment treaty between their home state and the host state includes ISDS provisions.

When disputes arise because of WTO violations, it becomes an international legal process through the WTO, arbitrated between states. When these types of disputes are arbitrated, elements of power politics, both on an international scale and domestic interests, come into play. Examples of this can be seen with India and Brazil as emerging powers (see Mahrenbach, 2016). By comparison, ISDS involves arbitration between states and corporations. While ICSID provides a legal framework for agreed-upon rules and arbitration processes, a variety of international tribunals may come into play throughout the dispute settlement process. Importantly, this means that the home state does not have to get involved on the corporation’s behalf, which could raise a variety of international political implications and politicization. The politicization of investment treaty disputes is an area of research that warrants further study (see Gertz and Poulsen, 2018).

Further comparing ISDS with the WTO dispute settlement process, we can explore how often each method is used. Since its inception in 1995, the WTO generally has seen a decline in requests for the establishment of a panel to arbitrate disputes (Mavroidis & Johannesson, 2017). The number of treaty-based ISDS cases has continued to rise over the same time period (UNCTAD, 2021). ISDS cases have also accumulated rapidly over the past 10 years (Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment 2022). There are also simply more corporations able to bring forth cases for arbitration than there are countries bringing forth WTO violations. However, noticing trends for both helps us to better understand the ever-changing international financial institutions and political climate. Investment and trade go hand in hand when it comes to the global economy.

Example Scenario: ConocoPhillips v. Venezuela

To help understand ISDSs, let’s consider a real-life scenario involving ConocoPhillips Inc. and Venezuela. ConocoPhillips is a Netherlands-based company that is a major player in the global energy sector. Venezuela is a country located in South America with one of the largest oil reserves in the world. The two parties were involved in a lengthy legal battle over a crude oil investment. To understand the context, it’s important to examine the original relations to international investments, politics, and the provisions of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) that were involved in the case.

Venezuela’s petroleum industry focuses on “extra-heavy” oil. Because of the complex molecular structure of extra-heavy oil, developing and operating refineries capable of handling it requires substantial investment in technology and infrastructure (ICSID, 2013). In order to reduce the barrier to entry into the Venezuela oil market, the Venezuelan government launched the Apertura Petrolera— or “Oil Opening”—in 1975. The Apertura Petrolera plan subsidized investment in the oil sector, encouraging private investment to improve Venezuela’s oil production, and it led to ConocoPhillips investing in Venezuela.

In 1991, ConocoPhillips and Venezuela signed an investment agreement that allowed the Dutch company to extract, transport, and refine extra-heavy crude oil from Venezuela’s soil. The production-sharing agreement awarded Venezuela 49.9% of the earnings from the produced barrels, with Conoco keeping the rest. This agreement was an exemplary partnership between an experienced industry player and a country that sought to gain profits from its resources. The original duration of the agreement was 35 years.

For almost a decade, things went smoothly, but in 1999, when the new president Hugo Chavez took office, his government implemented specific measures that ConocoPhillips perceived as expropriation of its assets without providing sufficient compensation and a violation of the original agreement. These measures started with changes in the legal framework, including the New Hydrocarbons Law, which imposed restrictions on private companies in the oil sector. It required private companies to operate through mixed enterprises with the home state holding a majority stake, and royalty rate disputes where Venezuela sought to increase royalty rates for oil projects, including those involving ConocoPhillips.

These operations restrictions led to disagreements and objections from ConocoPhillips regarding the legitimacy of these rate increases and their conformity with the existing agreement. Over time, the measures started to become increasingly problematic for Conoco. On January 31, 2007, ConocoPhillips formally transmitted a letter to the government of Venezuela, notifying them of the existence of a formal dispute arising under the Investment Law and the Treaty. In February 2007, President Chávez issued Decree Law 5,200, which mandated the conversion of oil projects into mixed companies with majority state ownership, which exceeded the 50% already stated in the original treaty. Despite lengthy negotiations, no agreement was reached between ConocoPhillips and Venezuela regarding the terms of participation in the new mixed companies as mandated by Decree Law 5,200. On June 26, 2007, Venezuela proceeded with the expropriation of ConocoPhillips Petrozuata, Hamaca, and Corocoro Projects.

ConocoPhillips immediately initiated arbitration proceedings against Venezuela, citing breaches of the investment agreement, including unlawful expropriation without fair and adequate compensation. ConocoPhillips, as the claimant, submitted a detailed claim statement outlining the alleged breaches of the Investment Law, the BIT, and international law by Venezuela. The claim focused on unlawful expropriation, failure to provide fair and equitable treatment, lack of protection and security, and arbitrary and discriminatory measures affecting ConocoPhillips’ investments in Venezuela. An arbitral tribunal was constituted to hear the case, typically comprising legal experts and arbitrators with expertise in international investment law. The arbitration process involved multiple rounds of hearings, submissions of evidence, and legal arguments. ConocoPhillips presented legal arguments and evidence to support its claims of breaches of the investment agreement and international legal standards, while Venezuela countered with its defense and justifications for its actions under domestic law and national interest considerations.

After carefully reviewing arguments and evidence, the arbitral tribunal issued its final award, valued at US$ 139,807,899 (ICSID, 2019). The tribunal considered factors such as the value of the assets confiscated, lost profits, and damages to determine the compensation owed by Venezuela. While the courts determined the compensation owed to ConocoPhillips, Venezuela contested aspects of the award and delayed compliance, resulting in further legal proceedings and negotiations. As of now, the award is being paid through a potential asset seizure of Citgo, a prominent American refiner and marketer of petroleum products. Citgo has been historically owned by PDVSA, the Venezuelan state-owned oil and gas company. The potential seizure arises from the possibility that Venezuela may not comply with the arbitration award voluntarily, leading to ConocoPhillips’ efforts to enforce the award through foreign assets.

This dispute sheds light on the complexities of international investment law, particularly the mechanisms for resolving disputes between foreign investors and host states. As of 2024, no awards have been granted to ConocoPhillips from Venezuela.

Criticisms and Implications

Though the goal of ISDS is to stay neutral, many critics have expressed their concerns that private investors have exploited the ISDS clause. Critics believe that successful investors with over 1 billion in annual revenue or high-income countries tend to file for claims (Columbia Center for Sustainable Investment 2022). Hence countries that have lower incomes are not financially able to file claims or even defend themselves because the loss of a case can have a significant impact on their economy. With that being said, developing countries tend to be victims of ISDS because they are an easy target for exploitation from multinational companies.

Another criticism that ISDS faces is that most of the case hearings happen behind closed doors and third parties are not taken into consideration (Allee & Peinhardt, 2010). ISDS cases are decided by three judge panels nominated and compensated by the investor and responding state; things such as human rights, workers’ rights, and community rights are not considered while deciding these cases. Treaties mostly impose binding obligations only on states, not investors; states generally cannot initiate or bring counterclaims in ISDS. So an investor may win a case even if it has violated domestic law, international human rights, or environmental norms in connection with the operation of the investment. While the primary benchmark that is considered while deciding an ISDS case is if principles of the appropriate investment treaty are used, critics argue that this broad aim can be exploited, especially given the lack of transparency in the process.

ISDS has a lot of leverage and case results may have negative consequences because environmental and human rights are not considered when passing judgments. Considering the multitude of effects, the general public tends to be collateral damage. An example of this is the case that occurred in 2009 between Chevron v. Ecuador. Chevron filed a case against Ecuador under a BIT in order to avoid the payment of a multi-billion-dollar court decision against the firm for the massive degradation of the Amazon rainforest. The Ecuadorian government discovered that their investor Chevron had been dumping toxic waste in the water, as well as digging hundreds of open-air oil sludge pits in Ecuador’s Amazon, leading to contaminating the communities of approximately 30,000 residents. Rather than complying with the orders of the Ecuadorian government, Chevron requested that the investor-state court review the decision that was made. Chevron also requested the court to force Ecuador’s taxpayers to pay billions of dollars in damages it may be required to pay to clean up the still-devastated Amazon, as well as all legal bills paid by the corporation in its investor-state dispute settlement. Chevron’s investor-state action seeks to re-litigate crucial points of the protracted domestic court case, including whether the affected communities had the right to challenge the firm in the first place (Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, 2015). Despite the environmental damage that Chevron had caused in the Ecuadorian community, Chevron is still able to file a case under the ISDS because the trade treaties have been “violated.” Furthermore, because of the company’s actions, indigenous communities living in that region of the Amazon virtually went extinct (Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch, 2015). This case shows that even though the treaty was made with good intentions, multinational companies have used ISDS to assist themselves resulting in the victimization of common people.

There are also instances where ISDS had a negative impact because it puts countries in a position where they must decide whether to use their resources to defend themselves against a lawsuit and uphold BITs or to help their civilians in a time of crisis. An example of this is with the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 was an uncontrollable external variable that impacted the ability of states to uphold the investment agreements they signed. COVID-19 has heavily impacted the ISDS process, as many states were not able to comply with the investment treaties they made prior to the pandemic. Investors can easily sue host states as they are bound by their investment treaty. New rules and regulations would have to be placed in order to preserve public health and ensure economic recovery. There have been multiple attempts to suspend treaty-based investor-state litigation for all COVID-19-related measures or establish the use of international law defenses in these rare circumstances. The idea behind this is that the primary goal should be to focus on the global crisis rather than focus on investment treaties.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) drafted the proposed agreement for the coordinated suspension of ISDS in April 2020 with respect to COVID-19-related actions and disputes. The agreement suspended the resolution of investor-state disputes with regard to claims that the responding signatory state believes to be concerning COVID-19-related measures. A provision relating this was added to investment treaties in effect between two or more signatories (Bernasconi-Osterwalder & Maina, 2020).

Finally, there have been questions about why powerful state actors would participate in the ISDS system and comply with ICSID. The initial reasoning is that signing BITs correlates with higher foreign direct investment, but this primarily benefits less developed countries. The incentive for powerful states to participate in the system could be connected to negative outcomes for non-participation. However, many states have found no such negative outcome. As of January 2024, the number of IIAs and ISDS cases has declined over the last decade (UNCTAD 2023). This could be attributed to several factors such as the COVID-19 outbreak, a decline in the publicity of cases, or a decline in the reasons for cases. Some research has raised concerns about the future of ISDS and the system’s stability (Johnson, 2016). Furthermore, ISDS is not immune to the enforcement issues of many international organizations. Currently, the primary mechanism for enforcing payouts is the risk of minimizing future investment or, in some cases, attempting to seize a state’s foreign assets (Financier Worldwide). This leaves states and MNCs with a substantial amount of leeway in deciding whether or not to comply with ISDS case outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, ISDS is a system of protection for private investors and states. Its primary goal is to provide a legal system for settling disputes between foreign investors and states. Bilateral investment treaties are the primary way in which investors and states agree to terms on foreign investment. ICSID, as a part of the World Bank Group, helps facilitate these investment treaties and provides a framework for arbitration and enforcement. Overall, this system has the intention to develop prosperity, especially for developing nations which often act as host states for foreign investment.

Though ISDS was made with good intentions and provides protection for both parties, throughout the years there have been concerns raised about the balance of power between large corporations and the developing countries they are investing in. Developing countries have limited legal resources and minimal grounds for recourse to prioritize the interests of their citizens on issues like environmental protection and human rights without risking arbitration. Because of these considerations, ISDS has received criticism as a system that benefits private investors at the expense of developing countries and their citizens. Additionally, damages being paid out from the host state to the foreign investors in the event the host state loses the arbitration process is one aspect of ISDS that has the potential to be politicized.

Countries that host foreign investment and agree to ISDS provisions must carefully balance domestic interests and foreign investors’ interests. COVID-19 has shown how compliance with investment agreements is complicated by evolving global externalities, as states must balance domestic concerns with foreign interests. States navigating domestic concerns of public health may be doing so at the risk of challenging agreed-upon terms for foreign investments. Nevertheless, states agree to the enforcement of ISDS provisions when signing investment treaties, with the understanding that the domestic situation or international landscape may change outside of their control. There are questions raised as to the role of global institutions in intervening in situations like this, even if the agreement is between a corporation and a state and not a state-to-state agreement.

Future research might explore how ISDS provisions between states continue to evolve. Although this chapter focused primarily on FDI between a developed home state and a developing host state, investment treaties also exist between developed states. As the global economy develops and developing countries continue to industrialize and move past primary sectors, there are additional considerations for the kinds of foreign investments received and how that may impact the host state’s citizens. This chapter has mentioned concerns about environmental impact and human rights as a part of foreign investment; future research into the treaties themselves and the effectiveness of including specific provisions around the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals might yield interesting insights. Generally speaking, the effectiveness of BITs and the ISDS arbitration methods is an area of research that could use more study. Research questions could explore the effectiveness of ISDS and how it affects relationships between states when provisions are broken.

ISDS is unique among international institutions that handle disputes between states, in that it focuses on multinational corporations and state disputes rather than state-to-state disputes. As international financial institutions evolve with shifting international politics, so too will the scope and specific provisions of ISDS evolve as countries become more experienced with the ISDS process and citizens continue to raise concerns about the ways in which countries agree to foreign investments.

Works Cited

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2010). Delegating differences: Bilateral investment treaties and bargaining over dispute resolution provisions. OUP Academic. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://academic.oup.com/isq/article/54/1/1/1789480

Bernasconi-Osterwalder, N., Brewin, S., & Maina, N. (2020). Protecting Against Investor–State Claims Amidst COVID-19: A call to action for governments. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://www.iisd.org/system/files/publications/investor-state-claims-covid-19.pdf

Beunder, A., & Mast, J. (2019). As the world meets to discuss ISDS, many fear meaningless reforms. Longreads. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://longreads.tni.org/isdsmany-fear-meaningless reforms.

Blanton, & Blanton, R. G. (2006). Human Rights and Foreign Direct Investment: A Two-Stage Analysis. Business & Society, 45(4), 464–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650306293392

Bossio, D., Erkossa, T., Dile, Y., McCartney, M., Killiches, F., & Hoff, H. (2012). Water Implications of Foreign Direct Investment in Ethiopia’s Agricultural Sector. Water Alternatives, 5(2), 223–242.

Bousso, Ron, David French, and Marianna Parraga. “Exclusive: Elliott Weighs Citgo Bid as Creditor Group Eyes Conoco for Own Offer.” Reuters, April 18, 2024. Accessed on April 23, 2024, from https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/elliott-weighs-citgo-bid-creditor-group-eyes-conoco-own-offer-2024-04-18/.

Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment (2022). Primer on International Investment Treaties and Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://ccsi.columbia.edu/content/primer-international-investment-treaties-and-investor-state dispute-settlement

ConocoPhillips Company V. Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Investment Policy, September 3, 2013. Retrieved on April 17, 2024 from https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement September 3, 2013.

CONOCOPHILLIPS v. BOLIVARIAN REPUBLIC OF VENEZUELA. Investment Policy, August 29, 2019. Retrieved on April 17, 2024 from https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement/cases/245/conocophillips-v-venezuela.

FitzGerald, A. G., & Valasek, M. J., (2017). Frequently asked questions about investor-state dispute settlement. Norton Rose Fulbright. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en/knowledge/publications/8014c6b7/frequently-asked-questions-about-investor-state-dispute-settlement

Gertz, G., Jandhyala, S., & Poulsen, L. N. S. (2018). Legalization, diplomacy, and development: Do investment treaties de-politicize investment disputes? World Development, 107, 239–252. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.02.023

Investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS). (n.d.) Picture Human Rights. Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://www.picturehumanrights.org/isds

Johnson, Lise, and Lisa E. Sachs. “The Outsized Costs of Investor-State Dispute Settlement.” AIB Insights 16, no. 1 (February 1, 2016). https://doi.org/10.46697/001c.16894.

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Bilateral Investment Treaty. Cornell Law School. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/ wex/bilateral_investment_treaty

Mahrenbach, L., C. (2016). Emerging Powers, Domestic Politics, and WTO Dispute Settlement Reform. International Negotiation, 21(2), 233–266. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718069-12341332

Mavroidis, P. C., & Johannesson, L. (2017). The WTO Dispute Settlement System 1995-2016: A Data Set and its Descriptive Statistics. Journal of World Trade, 51 (Issue 3), 357–408. https://doi.org/ 10.54648/trad2017015

Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. (2015) Case studies: Investor-state attacks on … – public citizen. Case Studies: Investor-State Attacks on Public Interest Policies. Public Citizen. Retrieved April 22, 2022, from https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/ uploads/egregious-investor-state-attacks-casestudies_4.pdf

“Roundtable: International Arbitration.” Financier Worldwide, April 2024. Retrieved on April 23, 2024, from https://www.financierworldwide.com/roundtable-international-arbitration-apr24.

United States Trade Representative (2014). The facts on Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/blog/2014/March/Facts-Investor-State%20Dispute Settlement-Safeguarding-Public-Interest-Protecting Investors

The History of the ICSID Convention. (n.d.). International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). Retrieved April 16, 2022, from https://icsid.worldbank.org/resources/publications/the-history-of-the-icsid-convention.

“Spotlight on Icsid Membership.” ICSID, November 10, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2024 from https://icsid.worldbank.org/news-and-events/speeches-articles/spotlight-icsid-membership.

“World Investment Report 2023.” UNCTAD, July 5, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2024, from https://unctad.org/publication/world-investment-report-2023.

UNCTAD. (2021) Investment flows to developed economies slumped by 58% in 2020. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021). Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://unctad.org/press-material/investment-flows-developed-economiesslumped-58-2020.

UNCTAD. (2021) Investor-State Dispute Settlement Cases: Facts and Figures 2020. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Retrieved April 19, 2022, from https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaepcbinf2021d7_en.pdf

UNCTAD (2023). “Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator.” Investment Policy, December 31, 2023. Retrieved April 19, 2024 from https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/investment-dispute-settlement.

United Nations. (n.d.). The 17 goals | sustainable development. United Nations. Retrieved April 21, 2022, from https://sdgs.un.org/goal