11 Finance: Sovereign Debt

Learning Objectives

- Define sovereign debt and outline how it affects the global economy and international politics, including examples of different varieties of sovereign debt.

- Outline the most common types of sovereign debt as it relates to IPE.

- Identify who our key players are in the global economy and how different ideologies can lead to high borrowing/lending.

- Evaluate a country’s risks for borrowing as well as the consequences of trusting certain lenders.

- Apply concepts that help guide us through sovereign debt and analyze the dynamics within sovereign debt.

In simple terms, sovereign debt is a term used to describe how much money a country’s government owes. This kind of debt refers to money owed by sovereign states to public and or private creditors, which can result in serious implications on the global economy and the debtor country. In a lot of cases, governments borrow for their respective countries so that they can increase spending without raising taxes (Pettinger, 2018), continue funding commitments like hospitals and schools during economic hardships such as a recession, and invest in the country’s future (Abbas & Pienkowski, 2022). Additionally, the majority of the time, countries borrow money to continue funding public services without having to cut expenses during a recession, this practice is known as “tax smoothing” (Abbas & Pienkowski, 2022).

However, the act of lending money to a country can lead to numerous complications when the debtor country is unable to pay back its loans. In many cases, the countries that receive the most from lenders are countries that are considered credible and not at a huge risk of nonpayment or even defaulting on loans; this is known as the reputation theory. For example, a country that isn’t considered a liability for lenders is the U.S., and an example of a country that may be considered a risk for lenders would be Greece, which took out substantial loans to fund projects for the Olympics in 2004 that they later were unable to pay off. A bad reputation or high debt levels doesn’t always come from the inability to repay debt but it can sometimes be a consequence of “natural disasters, or external shocks such as commodity price volatility or unexpected changes in capital flows” (UNCTAD, 2015). However, regardless of the reasons, inability to repay debt can lead to an increase in a country’s cost of borrowing, ruin its reputation, higher borrowing costs, political instability, spillovers, and sometimes even economic collapse.

The topic of sovereign debt is not one that can be escaped; debt is a constant cycle and due to recent events, it has continued to be a hot topic in research. Today, the practice of debt restructuring has become an important new topic of conversation due to the debt ceiling crisis in the United States, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war. Past national debt issues have resulted in more serious research on debt sustainability, fiscal policy, budget management, debt restructuring, and the impacts of debt like financial instability and inflation. New practices like the development of programs like the Government Debt and Risk Management Program have emerged to focus on institutional strengthening and technical capacity development (World Bank). Additionally, transparency practices between sovereign states and budget changes based on past debt issues have become a main priority. Finally, this chapter will provide an overview of sovereign debt by diving into its risks, history, past case studies on debt crises, and any related payback theories, highlighting the severity of the topic and its impact on the global economy.

Related Concepts and Theories

Sovereign debt used to be labeled as low risk, but when a country’s spending surpasses the money they take in and they begin drowning in debt that surpasses its GDP, fear arises. When this happens, questions like do these countries have a plan to repay? do they have a weak economy? and who is the owner of the debt? begin to circulate. Although these questions are all valid when debt becomes complicated, the most crucial issue is a country’s ability to repay, which leads us to the ultimate question: why do sovereign states repay?

In most cases, lenders loan money to a state to increase soft power and influence, take cash off of their hands and place it into the market for a return on investment, or as a form of assistance to a state in need of funds (Wright 2013). However, when a private or public lender decides to loan money to a state, they first must determine if this makes fiscal sense for their government. This question leads us to the reputation theory, developed by Michael Tomz, which argues that the borrower state’s reputation is what guides the creditor’s decision to loan them money, and the borrower state is incentivized to repay the loan to maintain their reputation in global credit markets (Tomz 2007). Tomz believes when an investor is deciding whether to lend to a government or not, they first take a look at the borrower’s history of repayment, and their positive relations with creditors. Put simply, this theory is similar to how credit cards and credit score work; when someone avoids maxing out their accounts and pays their bills on time, they get a better credit score which then gives them a better reputation that helps them open up new lines of credit and take out loans. Additionally, the reputational theory “predicts how investors treat first-time borrowers and how risk premiums evolve as borrowers become more seasoned” and helps explain why states with good reputations sometimes default ( Tomz, 2007).

Tomz theorizes the following: new borrowers will be faced with higher interest rates than a more seasoned borrower to lower the risks that come with lending to a potential lemon, one of three types of borrowers who are expected to not pay back or at least make consistent payments on loans. Similarly, the contextual inference is important to Tomz; investors will show low regard for debtors who default without a valid excuse while upgrading debtors who exceed expectations.

The additional two types of borrowers, according to Tomz, are stalwarts; borrowers who almost always repay their loans regardless of good times or bad, and fairweathers; borrowers who will make consistent payments to repay their debt only during good times, not bad. Tomz then goes on to argue that the concept of reputation has “sustained lending and repayment across the centuries,” and is “the first test of a government bond, and governments regularly articulate a reputational rationale for repaying their loans” (Tomz, 2007). Additionally, as a consequence of not repaying, borrowers will be unable to borrow in the future because their disregard for foreign commitments has put off investors. However, regardless of the reputation for repayments on loans, we see countries with different reputations receive loans, why is that?

Most sovereign states do not take on debt with the intention of not paying it back and gaining a bad reputation and not all lenders place importance on reputation when there will be financial gain. This simple fact renders the reputational theory somewhat useless; at the end of the day, there will always be money to lend and regardless of reputation, if a sovereign state has the extra money to lend and potentially get it back with gained interest, they will gladly give out loans. Taking the limitations of Tomz’s reputational theory into account, additional mechanisms guiding the nature of lending and borrowing between states and public or private creditors have shed some light on the situation. Some of these mechanisms, authored by Panizza, Sturzengger, and Zettelmeyer, include direct punishments on the defaulting state, domestic costs, and the threat of overseas asset seizures. Altogether, these mechanisms criticize the reputational theory and further prove that the evidence provided by Tomz does little to lend support to the argument that sovereign debt is “based on maintaining a good reputation in credit markets” (Panizza, Sturzenegger, and Zettelmeyer, 2009).

New theories provided by Panizza, Sturzenegger, and Zettelmeyer first focus on direct punishments being a motivator for sovereign states to repay their debts. These punishments include an increase in the cost of borrowing, sanctions or super sanctions, trade retaliation, and capital market exclusion. Since sovereign debt has limited legal penalties and mechanisms to enforce repayment, direct punishments can be used to “interfere with a country’s current transactions, trade, and payments” (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 661). Incentives to repay debt do not always have to be direct threats of punishments by creditors but rather threats of collateral damage to a debtor country’s economy and or government. However, looking back in history, direct threats of punishment, whether from creditors themselves or the credit market, seem to have stimulated more repayment than reputation.

A more serious punishment is sanctions or super sanctions, such as gunboat diplomacy which can be described as the use of military force to obtain foreign policy objectives. In their paper on Supersanctions and Sovereign Debt Repayment, Mitchener and Weidenmier (2005) argue that in the gold standard period, nations that were unable to repay and defaulted, faced the risks of blockades around their ports and the seizing control over their country, however this method of gunboat interventions is not common today. However, a more influential form of direct punishment is trade retaliation. After conducting a study, Andrew K. Rose (2005) found that “debt negotiations are associated with a decline in bilateral trade of approximately 8% per year, and that defaults affect trade for a long period, 15 years (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 679). Additionally, sovereign debt defaults have negative consequences on export-focused industries but can also benefit import-competing firms if the trend of defaults reducing trade remains. Although this theory of trade retaliation does hold some truth, it still faces criticism because “the relationship between trade and default is not affected by including trade credit” and sovereign defaults have been found to be “negatively associated with domestic private firms’ access to foreign credit” (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 679).

Another form of punishment is capital market exclusion. Market exclusion is evident following a default, but the period between exclusion and regained access to capital markets is quite short; “in the 1980s, countries were excluded from markets for about four years on average after their defaults ended and after the 1980s, reassess following exit from default was even faster” (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 676). Additionally, to further criticize the reputation theory, countries that are seasoned defaulters seem to be excluded from capital markets for a shorter period than a first-time defaulter, and since “sovereign debt models based on reputation in capital markets dispensed with the assumption of permanent capital market exclusion,” when permanent exclusion is extremely rare, the reputation theory barely upholds. Lastly, an increase in the cost of borrowing after a default episode can be a reason to repay; but not a good one. Like market exclusion, costs of borrowing seem to increase immediately following a debt default but it doesn’t last for long, in fact, the effects defaults have on borrowing costs are small and eventually, they disappear; the effects are not long-lived and do “not seem to be a plausible deterrent of default” (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 677).

Finally, aside from direct punishments, domestic costs are also incentives for repayment. For domestic costs, debt defaults can further worsen a state’s bad output; “Sturzenenegger (2004) finds that default episodes are associated with a reduction in the growth of approximately 0.6 percentage points and if it comes with a banking crisis, growth can decrease by 3.3 percentage points” (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 679). Additionally, the domestic costs of defaults can be linked to political economy issues; defaults can lead to issues for the politicians and government officials that decide to default, such as the loss of their jobs or even damage to their current and future political careers. Since it has been shown, by Richard N. Cooper (1971) and Jeffrey A. Frankel (2005), that “currency devaluations are often followed by electoral losses of the ruling party and reduce the tenure of the chief of executive and minister of finance,” sovereign debt defaults can potentially have the same effect (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 682). Overall, defaults can result in a country’s GDP to dip below trend GDP, can increase the risk of a banking crises, and can “lead to a fall in FDI flows into a country”; all of which can incentivize sovereign states to repay (Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer 2009, 680).

How can Sovereign Debt Exist and Function?

There are many reasons for a state to repay loans such as maintaining reputation or “good faith,” and keeping a borrowing country as a profitable enterprise for foreign investors. Debtors usually borrow with intentions of repaying, but as stated earlier in the chapter, this doesn’t always happen. Not all theories of repayment hold; there will always be different challenges being faced by states and sometimes debtors are at risk of defaulting. Consequently, when a borrowing state defaults, both the creditor and debtor can lose billions of investment capital, so under what circumstances can sovereign debt exist and function?

Sovereign debt can be an effective tool for proper statecraft; specifically, it can be helpful for a borrowing state to increase funding without having a huge tax burden on its citizens. As long as states have the ability to make payments on money borrowed and repay on time, sovereign debt can then be viewed as low risk. Debtors can benefit economically from the foreign investment into their markets by helping support ambitious projects, infrastructure, boost domestic industries, etc. (Sovereign Debt 2018). Debtors want to operate in “good faith” which means fulfilling contractual obligations and this is how sovereign debt can exist by creditors giving reasonable loans and debtors honoring their commitment and creating policy that aids in repayment of loans. Sovereign debt is somewhat of a “give-and-take” relationship and creditors will always look to invest with states that are considered low-risk and can usually repay loans.

Creditors can benefit from loaning out money because it is a way for states to put assets into the global market and hopefully get a return on investment. However, they can run a risk of defaulting or taking “haircuts” and not getting the return on the investment they sought. States that lend have the authority to influence or compel borrowing states to repay by excluding states from foreign markets, freezing assets in international banks, gunboat diplomacy, and placing economic sanctions on a borrowing state (ICMA 2017). This gives creditors more leverage and confidence when loaning money which in turn benefits debtors that need foreign investments. The constant flow of funds is what keeps the global economy functioning at its maximum potential, but for this to be the case, states need to ensure that they can trust their money in borrowing states. Theories such as reputation and punishment illustrate sovereign debt as an entity that states can evaluate risk and thus only invest in stalwart or even fairweather borrowers (Tomz 2007). This can be effective in most cases but there are exceptions, states will invest in risky borrowers or lemons if the creditor feels as though the benefits outweigh the risks (Tomz 2007). Creditors that feel that they can effectively gain collateral if a debtor defaults, will gladly run the risk of loaning money (Sovereign Debt 2018). This means that even under unfavorable conditions, state creditors will make exceptions and lend money if it results in a profit or at least increased soft power.

The important thing to note here is that sovereign debt can exist and function by giving the debtor much-needed funding for domestic projects. The creditor gets to invest money that could otherwise be sitting around; a chance to earn interest and increase soft power around the globe. Even nations with poor borrowing histories can entice creditors because these states can increase punishment if the borrowing government defaults (Shalal 2023). Include higher interest rates and extend their reach into new territory (Shalal 2023). As long as creditors are willing to loan out money and debtors can make payments, sovereign debt is beneficial, and even good business practice in a lot of cases, and can promote global economic growth.

Why does a Country Default?

When a country defaults, the government is breaking its contractual obligation to repay a loan (Materson 2022). This can have serious implications on the global economy as well as the economy of the creditor and debtor. Countries that default on loans will be considered a higher risk on future loans and could even face permanent exclusion from certain markets. So for our purposes, we will discuss why a sovereign state defaults on a loan in the first place.

Before a state officially defaults there are several steps taken to try to avoid this. One example is that creditors will take a “haircut” which lowers the amount a debtor will have to pay in hopes of getting a partial return on an investment (Boyle & Rohrs-Schmitt 2022). When a debtor finally defaults on a loan the financial and economic impact can be severe on both parties; debtors that are dependent on foreign investment to boost their economy will see the national economy immediately slow down (Boyle & Rohrs-Schmitt 2022). A debtor can default on a loan due to many factors stemming from economic hardship such as war, corruption, revolution, financial mismanagement, or financial crisis (Boyle & Rohrs-Schmitt 2022). When states borrow from creditors they must also create smart fiscal policies that maximize the loans and leave avenues for repayment to be possible.

Some theories as to why states default on loans include Misfortune or sudden changes in the global market or domestically (Sovereign Default 2018). Natural disasters can affect a state’s ability to make payments on loans if the debtor has a decrease in liquid money. Spikes in global interest rates and a rise in prices can also cause a state to default (Sovereign Default 2018). We see this on a macro and microeconomic level as a 1% increase in interest rates can be the difference in a debtor’s capacity to afford a loan. The price increase can cause a state to default as well because the cost of operating has increased which can quickly make a loan obsolete and ineffective. The one criticism of the theories listed above is that experienced and fiscally smart governments should craft policy and borrow accordingly to include a buffer with unforeseen events in mind (Sovereign Debt 2018). Overall, debtors should not borrow if they are not confident or lack the capability to make payments on loans.

Case Studies in Sovereign Debt

From this point on, we’ll review a couple of important case studies in sovereign debt. First, we’ll look at a country that experienced a recent debt crisis—Greece. Their case is indicative of the stress austerity measures can inflict upon a domestic population. Then, we’ll talk about the nation with the highest debt-to-GDP ratio as of 2022—Japan. Multiple aspects of their scenario, including that they owe most of their debt to themselves, are unique. Both nations have interesting relationships with sovereign debt and they will demonstrate the various methods a nation can use to manage it. Lastly, we will discuss the U.S. sovereign debt, when it reached the highest in history, and the current national debt.

Case: Greece

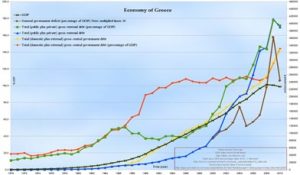

Many economists have been closely monitoring Greece as a recent example of a sovereign debt crisis. Despite being a member of the European Union since 1992, Greece has had a challenging economic relationship with the rest of Europe, particularly since the introduction of the euro. At the time, Greece was unable to adopt the Euro because it did not meet the fiscal requirements which included having inflation below 1.5 percent, a budget deficit below 3 percent, and a debt-to-GDP ratio below 60 percent. This was despite the Euro being introduced in 1999 with the expectation that all EU members would use one common currency. (Council on Foreign Relations). Fast Forward to 2001, Greece finally decided to get rid of its currency (drachma) and join the EuroZone- leading to the first step down the debt crisis.

As a result, Greece started borrowing a lot of money at cheap interest rates, which caused its debt to increase quickly. Greece was additionally subject to the same monetary policies as other eurozone members due to its membership in the currency union, regardless of its specific economic conditions. Soon this led to Greece being unable to devalue its currency in response to economic difficulties like high inflation or slow development because it no longer had authority over its currency. In 2001 the country received assistance from Goldman Sachs (2.8 billion euros) to set up a complicated financial transaction called a currency swap. Per the agreement, Greece swapped its existing debt, which was in US dollars and Japanese yen, for debt in euros. As a result of the currency swap, Greece was able to get a sizable upfront payment, which it used to lower its debt-to-GDP ratio and create the illusion that its economy was stronger than it was. The agreement caused controversy since it not only concealed the real size of the nation’s debt but also allowed Greece to borrow money at lower interest rates than it would have otherwise been able to.

Greece took its final economic hit in 2004 when it hosted the Summer Olympic Games. Costing $11.6 billion, the event raised their debt-to-GDP ratio to greater than 110%, prompting fiscal monitoring from the European Commission. Typically, Greece would be able to combat its rising debt by borrowing and spending more to obtain growth greater than its interest rates. In 2008, however, the global banking crisis (set off by the U.S. subprime mortgage market collapse) caused the cost of borrowing to rise to the point where Greece couldn’t afford to borrow at rates low enough to credibly repay. To prevent complete collapse, the EU provided Greece with roughly $146 billion in loans on the condition that the Prime Minister saw through austerity measures like significantly cutting government spending and increasing taxes. In 2010, the European Central Bank began its Securities Market Program wherein it would help struggling nations (like Greece) by buying some of their bonds. This would provide a stable stream of demand for nations with riskier bonds, boosting confidence among other investors. The main goal of this program was to maintain economic stability in Europe and prevent the spread of more sovereign debt issues across the continent.

In 2012, the EU and the IMF approved a new joint bailout of around $172 billion for Greece, which included a large debt write-down. (Essentially, a write-down occurs when it is realized that debt will not be paid back. Keeping the debt listed dishonestly markets that the money will be returned and can be depended on). After all these steps and some more minor revisions to Greece’s bailout, the debt situation began to normalize in 2014, with Greece issuing low-interest rate Eurobonds for the first time in four years. The provision of bonds was successful, and Greece raised a significant amount of money from them. After completing a third bailout in 2018, Greece now owes the EU and the IMF $330 billion—a debt-to-GDP ratio of roughly 180%. Greece has committed to running a budget surplus (taking in more money than what they spend) until 2060 to pay them back.

This case study of Greece demonstrates how risky it might be to have a big debt in a currency you have no control over.

Case: Japan

We are now going to turn to another case, the country with the highest debt-to-GDP ratio of any major economy in the world, Japan. In December 2022, Japan’s government debt represented 225.9% of its nominal GDP, up from 225.9% the previous quarter. (CEIC Data)

Despite having the highest debt-to-GDP ratio of any nation in the world, Japan’s own central bank owns roughly half of it. Regarding the portion owned by the Bank of Japan, one advisor of former Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said, “It is 500 trillion yen of borrowed money that in effect carries no interest and never has to be paid back,” (Landers, 2021). Also, since all of Japan’s debt is issued in yen, it is unlike other nations (Greece, for example) which have debts in a currency they can’t control. While Greece must repay creditors in Euros, which it can’t print, many Japanese economists take the position that they can simply print more yen when needed to satisfy their internal lending mechanism.

Since Japanese companies and customers tend to prefer saving their money over spending, government borrowing, and spending is the only effective method Japan has had to generate demand. Though printing too much money does run the risk of causing inflation, Japan has been stuck regarding that for decades, unable to meet the annual 2% mark they’ve been aiming for. Instead, they’ve languished at around 0%. This shows us that sovereign debt totals can be deceptive—though Japan has struggled greatly with economic growth in the 21st century, they haven’t had a significant debt crisis where they’ve been unable to pay back their lenders. Their system of internal lending is something the U.S. does as well, though only about 20% of U.S. debt is owed to itself as opposed to Japan’s 50%. When one needs to borrow and spend to create the demand necessary for growth, having the debts issued in one’s currency can provide truly unique opportunities to “look the other way” regarding the issue of sovereign debt altogether.

Case: The United States

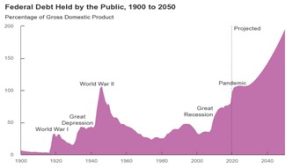

Looking at the U.S. sovereign debt, the U.S. government has been running a budget deficit for many years, which means that it spends more money than it brings in through taxes and other revenue sources. As a result, the government needs to borrow money to finance its spending, which adds to the national debt. In terms of the percentage of GDP, which is a commonly used measure to assess a country’s debt burden, the highest level of U.S. sovereign debt was around 106% of GDP in 1946, immediately after the end of World War II. The United States has had public debt for longer than it has existed as a nation, yet for more than a century and a half, it had managed to function without any, until the country joined World War I, and had to take out record-breaking amounts of debt. At that time, the U.S. government had incurred significant debt to fund its war efforts. However, the U.S. was able to reduce its debt burden over time, and by the 1970s, the debt-to-GDP ratio had fallen to around 30%. Since then, the debt-to-GDP ratio has increased again, and it reached a high of around 106% in 2021, due in part to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s efforts to stimulate the economy.

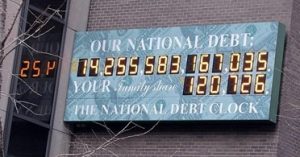

Speaking of today (2023), the public’s fear about federal spending is rising, and politicians from both parties say that cutting the budget deficit is one of their top priorities. The federal government’s $31.38 trillion debt ceiling has already been reached, which is believed to be the highest of all times. According to Statista, the forecast for the U.S. national debt in 2023 is believed to be 122.89% of the GDP and 134.87% in 2027.

Conclusion

After discussing sovereign debt both theoretically and practically, it can be concluded that there seems to be a significant correlation between the two. One of the ideas that effectively explains Greece’s issue with sovereign debt is the Tomz Reputational Theory. When one considers what Tomz said, that nations with stronger repayment reputations are more likely to receive loans at lower interest rates, it is clear how Greece’s economic instability led to a worsened reputation. The increase in interest rates that Greece had to pay to borrow money on the global bond market was one of the most obvious immediate repercussions. Following the debt crisis, several nations became more cautious when lending money to Greece and demanded higher interest rates in the event of a default. As a result, other nations began to enact stricter fiscal regulations and debt management procedures in order to prevent similar catastrophes.

Similarly, International bodies like the IMF and the European Commission have expanded their monitoring and oversight of countries’ economic policies as a result of the crisis. In their financing initiatives, these institutions started to focus more emphasis on the necessity of sustainable debt levels, structural changes, and economic stability, and nations that applied for aid had to meet stringent criteria before being granted loans. As Panizza, Sturzenegger & Zettelmeyer (2009) criticized the reputation theory, direct punishment such as increasing the cost of borrowing is not always the right measure or motivation for countries to repay, since it caused Greece to spiral down economically even more.

However, not all theories hold truth to them, especially not in the case of the United States. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the United States has been running a budget deficit for many years and is well known for having the most significant external debt in the world. However, the country’s reputation for not being able to repay its loans and its overaccumulation of debt has done nothing to stop it from continuously borrowing money, why is that?

Contradicting the reputational theory, the United States has no incentive to repay its loans based on reputation; its name has already been tainted but there seems to be no end to the debt crisis. Additionally, not many direct threats or punishments have been held over the United States to ensure repayment, ultimately making it a special case that contradicts almost all sovereign debt theories.

In conclusion, this chapter has defined and explored the complexity of sovereign debt, including related theories such as the Tomz reputation theory, reasons for repayment and defaulting, and case studies from Greece, Japan, and the United States. By examining and questioning these topics, we have recognized certain puzzles and future research topics that can use these studies to better analyze current debt issues, including the US debt ceiling crisis and the rising sovereign debt issues across the globe caused by the pandemic.

Due to the high risks that come with an over-accumulation of debt and defaulting, it is important that future research can look back on the theories, criticisms, and case studies, mentioned in the above chapter, to have a better understanding of sovereign debt management. In particular, past case studies, such as Greece’s debt crisis, can perhaps be applied to and offer insights into the US’s debt ceiling crisis by highlighting the long-term economic consequences of unsustainable debt levels, the challenges the debtor could potentially face if they default, and ways to prevent defaulting from happening. Additionally, these past case studies, as well as repayment theories, can further motivate responses to the pandemic-induced debt crisis we see today. As national debts are on the rise today due to the covid-19 pandemic, reasons to default as mentioned in the chapter can be tied back to today’s crisis and can expand research on debt relief initiatives and new solutions to promote economic recovery from global emergencies.

Overall, the study of sovereign debt is crucial in maintaining global financial stability and promoting economic recovery. Additionally, it is a complex continuous issue that will always require ongoing research and attention to sustain it and prevent risks. By addressing related topics, repayment, and defaulting theories, and case studies, as well as questioning them, we can look towards future research to expand on this and work towards responsible debt management.

Bibliography

Abbas, S.M A., and Alex Pienkowski. 2022. “What Is Sovereign Debt?” International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2022/12/basics-what-is-sovereign-debt.

Ams, J., Baqir, R., Gelpern, A., & Trebesch, C. (2018). Sovereign Default (p. 50) [Review of Sovereign Default]. (Original work published 2018).

Boyle, Michael J., Investopedia Team, and Kirsten R. Schmitt. 2022. “Sovereign Default: Definition, Causes, Consequences, and Example.” Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sovereign-default.asp.

Buchholz, Katharina, and IMF. 2022. “Chart: How National Debt Soared.” Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/23558/increase-national-debt/.

Congressional Budget Office. 2020. “File:US Federal Debt Held By Public as of Sep. 2020.png.” Wikimedia Commons. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:US_Federal_Debt_Held_By_Public_as_of_Sep._2020. png.

DeSilver, Drew. 2023. “5 facts about the U.S. national debt.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/02/14/facts-about-the-us-national-debt/.

Howarth, David, and Lucia Quaglia. 2015. “The political economy of the euro area’s sovereign debt crisis: introduction to the special issue of the Review of International Political Economy.” Taylor & Francis Online.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09692290.2015.1024707?journalCode=rri p20.

Masterson, Victoria. 2022. “Why do countries default on their debts? | World Economic Forum.” The World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/russia-default-debt-crisis/.

Milligan, Susan. 2023. “CBO: U.S. Debt Growing Dramatically Worse as Lawmakers Quibble Over Borrowing Cap.” USNews.com. https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/2023-02-15/cbo-u-s-debt-growingdramatically-worse-as-lawmakers-quibble-over-borrowing-cap.

“National Debt by Country / Countries with the Highest National Debt 2023.” n.d. World Population Review. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-by-national-debt.

Nelson, Rebecca M., Martin A. Weiss, Derek E. Mix, and Paul Belkin. 2012. “The Eurozone Crisis: Overview and Issues for Congress.” Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R42377.pdf.

O’Neill, Aaron. 2023. “U.S.: National debt in relation to GDP 2027.” Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/269960/national-debt-in-the-us-in-relation-to-gross-do mestic-product-gdp/.

Panizza, Ugo, Federico Sturzenegger, and Jeromin Zettelmeyer. 2009. “The Economics and Law of Sovereign Debt and Default.” Journal of Economic Literature 47, no. 3 (September): 651-98. 10.1257/jel.47.3.651.

Pettinger, Tejvan. 2018. “Why does the Government Borrow?” Economics Help. https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/5481/economics/why-does-the-government-borrow/

Prieur, Benoît. 2011. “File:NYC National Debt Clock.JPG.” Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:NYC_National_Debt_Clock.JPG.

Reich, Robert B. 2015. “How Goldman Sachs Profited From the Greek Debt Crisis.” The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/goldmans-greek-gambit/.

Rogers, William A. 1928. “1904 cartoon: Theodore Roosevelt and his Big Stick in the Caribbean.” Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tr-bigstick-cartoon.JPG.

Shalal, Andrea. 2023. “Debtors, Creditors Agree Steps to Jumpstart Debt Restructurings.” Reuters, April 13, 2023, sec. World. https://www.reuters.com/world/sovereign-debtors-creditors-agree-steps-jumpstart-debt-re structurings-2023-04-12/.

Thanatostalk, C.M Reinhart, World Bank, and Eurostat. 2012. “File:HellenicOeconomy(inCurrentEuros).png.” Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HellenicOeconomy(inCurrentEuros).png

“Timeline: Greece’s Debt Crisis.” n.d. Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/greeces-debt-crisis-timeline.

Tomz, Michael, and Mark L. Wright. 2013. “Empirical Research on Sovereign Debt and Default.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2239522.

United Nations UNCTAD. 2015. “Roadmap and Guide for Sovereign Debt Workouts.” UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsddf2015misc1_en.pdf.

World Bank. n.d. “Government Debt and Risk Management Program.” World Bank. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/government-debt-and-risk-management-pr ogram.