19

Dr. Evan Freeman

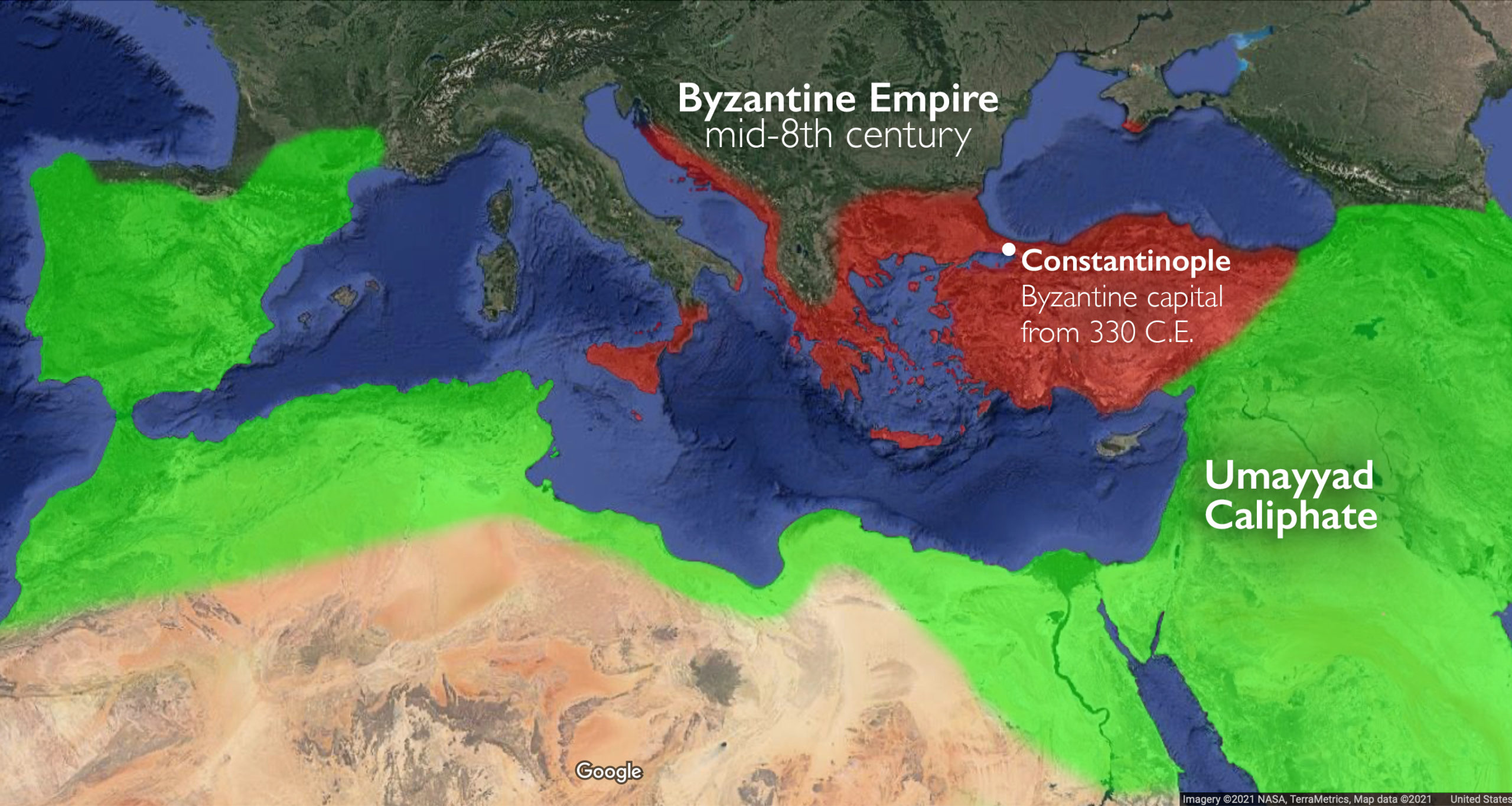

The “Iconoclastic Controversy” over religious images was a defining moment in the history of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. Centered in Byzantium’s capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) from the 700s–843, imperial and Church authorities debated whether religious images should be used in Christian worship or banned. Who were the players and what was this Controversy all about?

Key Terms

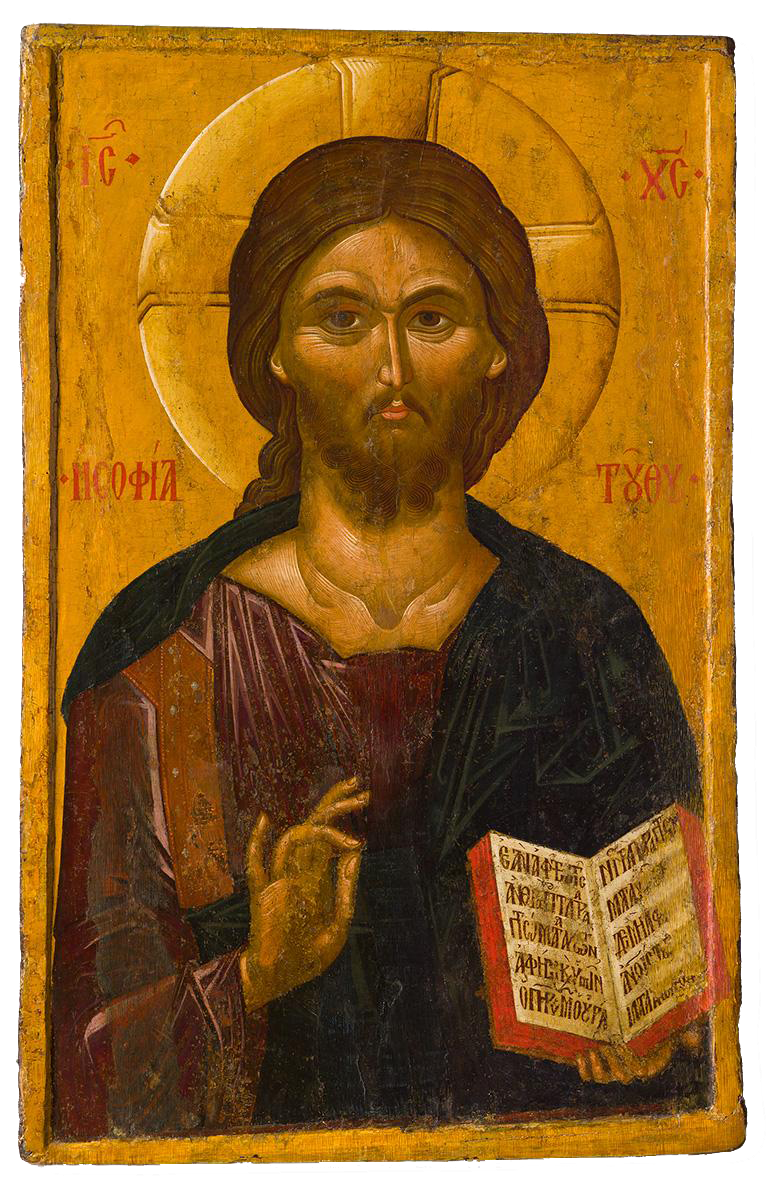

Icons (Greek for “images”) refers to the religious images of Byzantium, made from a variety of media, which depict holy figures and events.

Iconoclasm refers to any destruction of images, including the Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries, although the Byzantines themselves did not use this term.

Iconomachy (Greek for “image struggle”) was the term the Byzantines used to describe the Iconoclastic Controversy.

Iconoclasts (Greek for “breakers of images”) refers to those who opposed icons.

Iconophiles (Greek for “lovers of images”), also known as “iconodules” (Greek for “servants of images”), refers to those who supported the use of religious images.

What was the big deal?

Debating for over a century whether religious images should or should not be allowed may puzzle us today. But in Byzantium, religious images were bound up in religious belief and practice. In a society with no concept of separation of church and state, religious orthodoxy (right belief) was believed to impact not only the salvation of individual souls, but also the fate of the entire Empire. Viewed from this perspective, it is possible to understand how debates over images could entangle both Church leaders and emperors.

The arguments

The iconophiles and iconoclasts developed sophisticated theological and philosophical arguments to argue for and against religious images. Here is a quick summary of some of their main points:

The iconoclasts noted that the Bible often prohibited images, notably in the Second Commandment (one of the Ten Commandments appearing in the Hebrew Bible):

You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them….(Exodus 20:4–5, NRSV)

The iconophiles countered that while the Bible prohibited images in some passages, God also mandated the creation of images in other instances, for example God commanded that cherubim (winged angelic beings) should adorn the Ark of the Covenant: “You shall make two cherubim of gold; you shall make them of hammered work, at the two ends of the mercy seat.” (Exodus 25:18, NRSV). (According to the Hebrew Bible, the Ark of the Covenant was a wooden chest covered with gold containing the tablets on which the Ten Commandments were inscribed; the mercy-seat was the gold cover on the Ark, which was understood as God’s resting place.)

The iconoclasts argued that God was invisible and infinite, and therefore beyond human ability to depict in images. Since Jesus was both human and divine, the iconoclasts argued that artists could not depict him in images. The iconophiles agreed that God could not be represented in images but argued that when Jesus Christ, the Son of God, was born as a human being with a physical body, he allowed himself to be seen and depicted. Since some icons were believed to date to the time of Christ, icons were understood to offer a kind of proof that the Son of God entered the world as a human being, died on the cross, rose from the dead, and ascended into heaven—all for the salvation of humankind.

The iconoclasts also objected to practices of honoring icons with candles and incense, and by bowing before and kissing them, in which worshippers seemed to worship created matter (the icon itself) rather than the creator. But the iconophiles asserted that when Christians honored images of Christ and the saints like this, they did not worship the artwork as such, but honored the holy person represented in the image.

Timeline of events

Early centuries

Sporadic evidence of Christians creating religious images and honoring them with candles and garlands emerges from as early as the second century C.E. Church leaders often condemned such images and devotional practices, which seemed too similar to the pagan religions that Christians rejected.

The seventh century

The Byzantine Empire faced invasions from Persians and Arabs in the seventh century, resulting in significant loss of territory. Trade decreased and the empire experienced an economic downturn. Byzantine anxieties over images likely emerge, at least in part, as a result of these devastating events (which may have been perceived as signs of God’s displeasure with icons).

*

Through the centuries, icons became increasingly widespread in Byzantium. By the late seventh century, the Church began to legislate on images. Church leaders at the Quinisext Council (also known as the Council of Trullo) held in Constantinople in 691–92 prohibited the depiction of crosses on floors where they could be walked on, which was understood as disrespectful. They also mandated that Christ be depicted as a human rather than symbolically as a lamb in order to affirm Christ’s incarnation and saving works. Around this same time, emperor Justinian II (reigned 685–94 and 705–71) incorporated icons of Christ onto his coins. These events suggest the growing importance of religious images in the Byzantine Empire at this time.

The first phase of Iconoclasm: 720s–787

Historical texts suggest the struggle over images began in the 720s. According to traditional accounts, Iconoclasm was prompted by emperor Leo III (who reigned 717–41 and was the founder of the Isaurian Dynasty) removing an icon of Christ from the Chalke Gate of the imperial palace in Constantinople in 726 or 730, sparking a widespread destruction of images and a persecution of those who defended images. But more recently, scholars have noted a lack of evidence supporting this traditional narrative, and believe that iconophiles probably exaggerated the offenses of the iconoclasts for rhetorical effect after the Controversy.

Historical evidence firmly identifies Leo’s son, emperor Constantine V (reigned 741–75), as an iconoclast. Constantine publicly argued against icons and convened a Church council that rejected religious images at the palace in the Constantinople suburb of Hieria in 754. Probably as a result of this council, iconoclasts replaced images of saints with crosses in the sekreton (audience hall) between the patriarchal palace and Constantinople’s great cathedral, Hagia Sophia, in the 760s (discussed further below).

787 Iconophile Council of Nicaea II

In 787, the empress Irene—who ruled as regent for her son Constantine VI from 780–90, as co-ruler with Constantine VI from 792–97, and as sole ruler from 797–802—convened a pro-image Church council, which negated the Iconoclast council held in Hieria in 754 and affirmed the use of religious images. The council drew on the pro-image writings of a Syrian monk, Saint John of Damascus, who lived c. 675–749.

The second phase of Iconoclasm: 815–843

Emperor Leo V, who reigned from 813–20, banned images once again in 815, beginning what is often referred to as a second phase of Byzantine Iconoclasm. Leo V’s ban on images followed significant Byzantine military losses to the Bulgars in Macedonia and Thrace, which Leo may have viewed as a sign of God’s displeasure with icons. Theodore, abbot of the Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople, wrote in defense of icons during this time. Evidence suggests this second phase of Iconoclasm was more mild than the first.

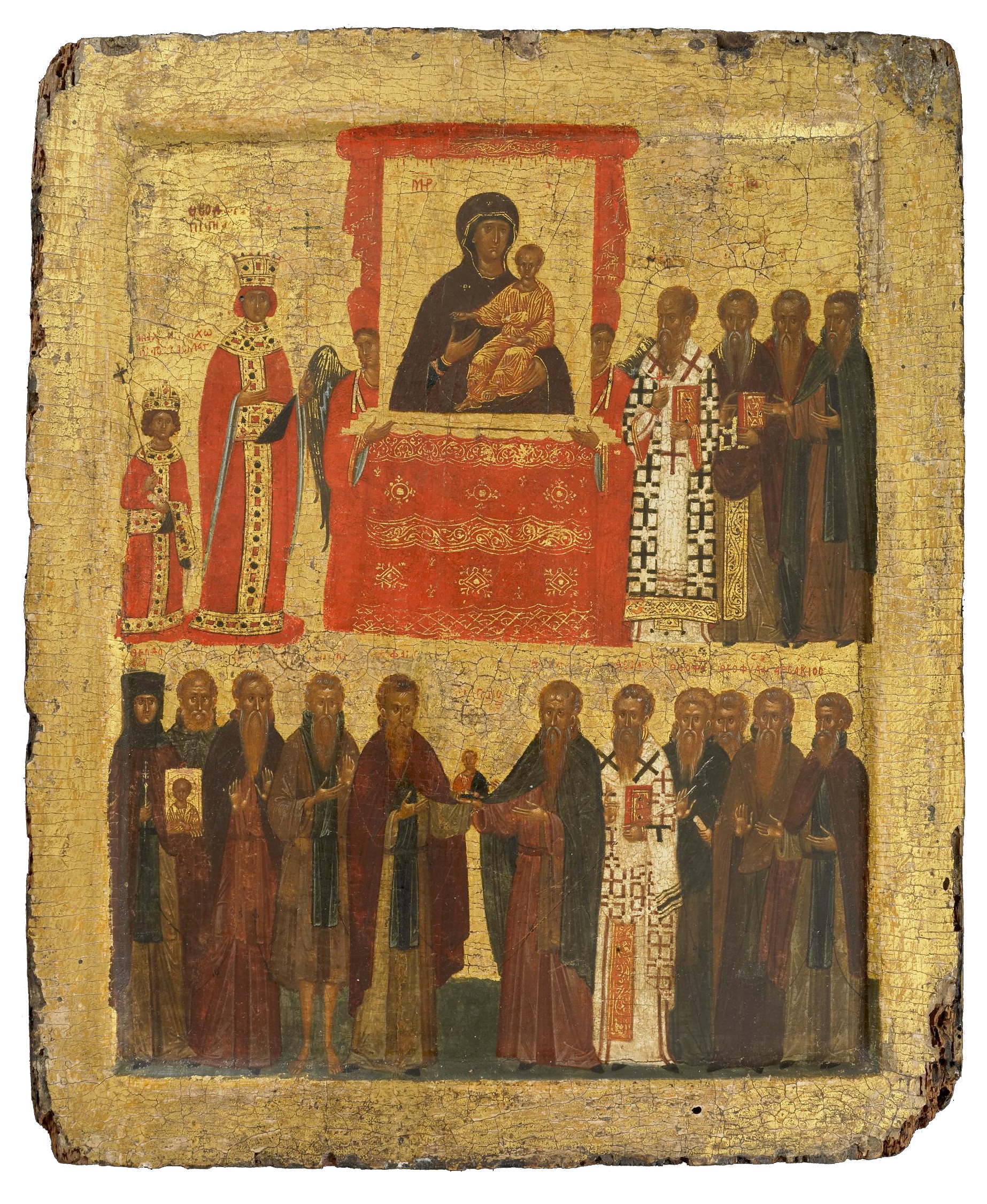

The Triumph of Orthodoxy

The iconoclastic emperor Theophilos, who assumed the throne in 829, died in 842. His son, Michael III, was too young to rule alone, so empress Theodora (Michael III’s mother), and the eunuch Theoktistos (an official), ruled as regents until Michael III came of age. Later sources describe Theodora as a secret iconophile during her husband’s iconoclastic reign, although there is a lack of evidence to support this. For reasons not entirely clear, Theodora and Theoktistos installed the iconophile patriarch Methodios I (who held this office from 843–47) and once again affirmed religious images in 843, definitively ending Byzantine Iconoclasm.

Imperial and Church leaders marked this restoration of images with a triumphant procession through the city of Constantinople, culminating with a celebration of the Divine Liturgy (a church service with hymnography, readings from the Bible, and the celebration of the Eucharist) in Hagia Sophia.

The Church acclaimed the restoration of images as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy,” which continues to be commemorated annually on the first Sunday of Lent in the Eastern Orthodox Church to this day. (Lent, or Great Lent, is an annual, 40-day period of fasting that precedes Holy Week and the celebration of Pascha, or Easter, in the Eastern Orthodox Church.)

Iconoclasm and the Triumph of Orthodoxy in Byzantine Mosaics

The Byzantine Iconoclastic Controversy was not merely an intellectual debate, but was also an inflection point in the history of Byzantine art itself. Let us consider the examples of three Byzantine churches, whose mosaics offer visual evidence of the Iconoclastic Controversy and subsequent Triumph of Orthodoxy: Hagia Eirene in Constantinople (Istanbul), the Dormition in Nicaea (İznik, Turkey), and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul).

Hagia Eirene in Constantinople

The emperor Justinian constructed the church of Hagia Eirene in Constantinople (Istanbul) in the sixth century, but the church’s dome was not well supported, and the building was badly damaged by an earthquake in 740. Emperor Constantine V, who reigned from 741–75, rebuilt Hagia Eirene in the mid to late 750s.

Constantine V—who, as an iconoclast, opposed pictorial depictions of Christ and the saints—is credited with decorating the apse of the church with a cross, which the iconoclasts found acceptable. The cross mosaic makes liberal use of costly materials, such as gold and silver. The skilled artists who created the mosaic bent the arms of the cross downward to compensate for the curve of the dome so that the crossarm would appear straight to viewers standing on the floor of the church.

Clearly, while the iconoclasts opposed certain types of religious imagery, they did not reject art entirely, and were sometimes important patrons of art and architecture, as was Constantine V. There is also evidence that emperor Theophilos—who reigned during the second phase of Iconoclasm—expanded and lavishly decorated the imperial palace and other spaces.

*

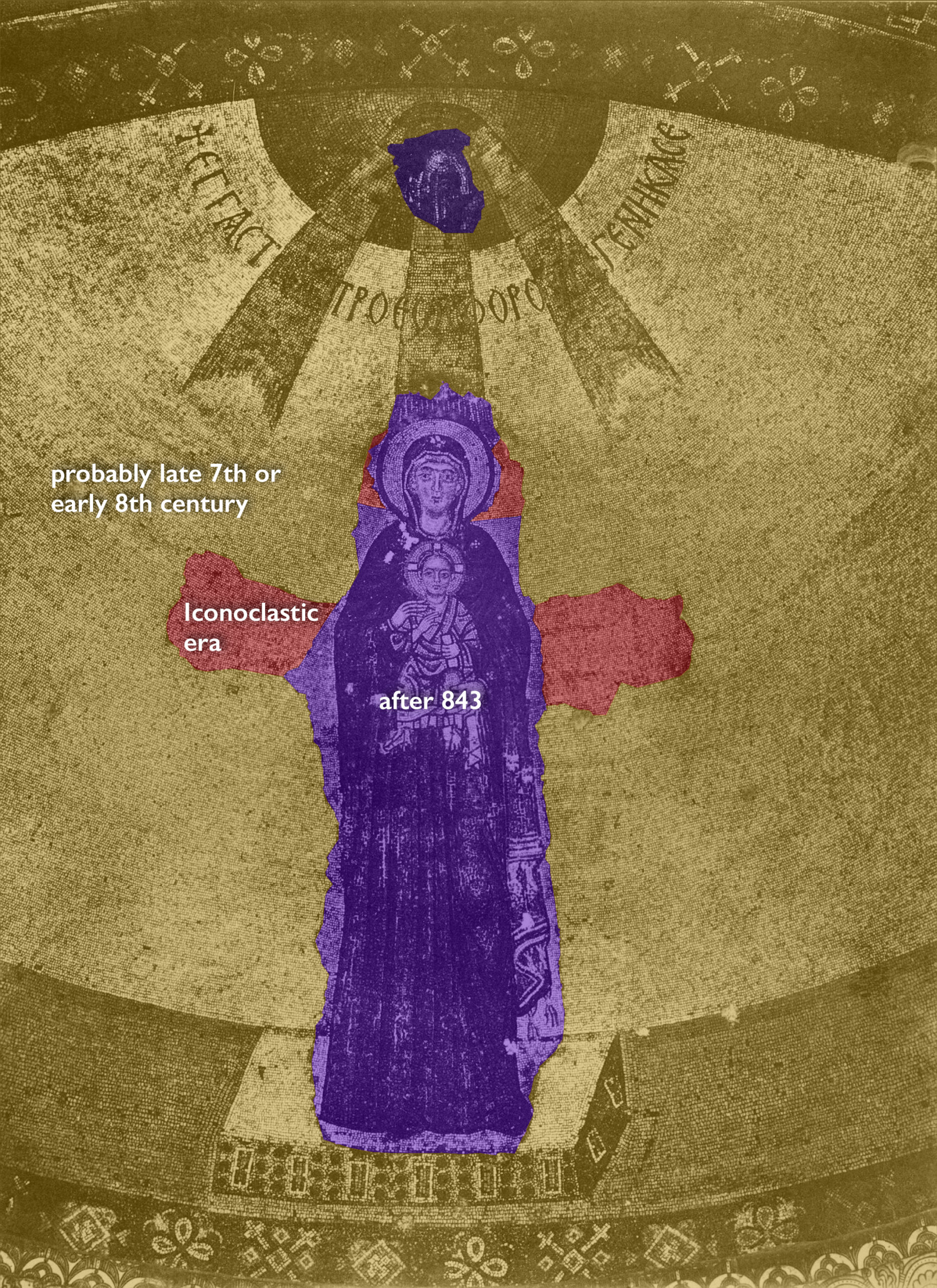

The church of the Dormition in Nicaea

Iconoclastic activity can be directly observed in the mosaics of the church of the Dormition (or Koimesis) at Nicaea (İznik, Turkey). Although the church does not survive today, photographs from 1912 clearly show seams, or sutures, where parts of the mosaics were removed and replaced during the Byzantine era.

Although the precise history of the mosaics at Nicaea is difficult to reconstruct, the 1912 photographs clearly indicate three distinct phases of creation and subsequent restorations during and after the Iconoclastic era.

Hagia Sophia in Constantinople

Iconoclasm in the sekreton

The only surviving evidence of destruction of images in the Byzantine capital survives at Hagia Sophia, in audience halls (sekreta) that connected the southwestern corner of the church at the gallery level with the patriarchal palace. Primary sources speak of patriarch Niketas—the highest-ranking Church official in Constantinople—removing mosaics of Christ and the saints from the small sekreton sometime between 766–69.

And as at the church of the Dormition in Nicaea, scars are visible in the mosaics in the small sekreton. Roundels with crosses, which survive today, likely once contained portraits of saints, which patriarch Niketas is said to have removed. Beneath the roundels, the ghostly remnants of erased inscriptions indicate where the missing saints’ names once appeared.

Apse mosaic and the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Following the Triumph of Orthodoxy, the Byzantines installed a new mosaic of the Virgin and Child in the apse of Constantinople’s Hagia Sophia. The image was accompanied by an inscription (now partially destroyed), which framed the image as a response to Iconoclasm: “The images which the imposters [i.e. the iconoclasts] had cast down here pious emperors have again set up.” Yet unlike at Nicaea, there is no evidence of the apse’s previous decoration or of any interventions by iconoclasts. So while the inscription implies that iconoclasts removed a figural image from this position, this ninth-century Virgin and Child mosaic installed after the Triumph of Orthodoxy may be the first such figural image to occupy this position in Hagia Sophia.

In 867, patriarch Photios, the highest-ranking Church official in Constan- tinople, preached a homily in Hagia Sophia on the dedication of the new mosaic. Photios condemned the iconoclasts for “Stripping the Church, Christ’s bride, of her own ornaments [i.e. images], and wantonly inflicting bitter wounds on her, wherewith her face was scarred. . . .” He went on to speak of the restoration of images:

[The Church] now regains the ancient dignity of her comeliness. . . . If one called this day the beginning and day of Orthodoxy . . . one would not be far wrong. Photios, Homily 17, 3

The mosaic in Hagia Sophia and the homily by Photios both illustrate how the iconophiles—the victors of the Iconoclastic Controversy—framed their victory as a triumph of religious orthodoxy, perhaps exaggerating the offenses of the iconoclasts along the way for rhetorical effect.

Additional resources

Charles Barber, Figure and Likeness: On the Limits of Representation in Byzantine Iconoclasm (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002).

Leslie Brubaker, Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm (London: Bristol Classical Press, 2012).

Robin Cormack and Ernest J. W. Hawkins, “The Mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: The Rooms above the Southwest Vestibule and Ramp,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 31 (1977): 175–251.

Paul A. Underwood, “The Evidence of Restorations in the Sanctuary Mosaics of the Church of the Dormition at Nicaea,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 13 (1959): 235–243.