21

Artwork in focus

Dr. Magdalene Breidenthal

A sparkling image of Christ’s crucifixion appears in gold and brightly-colored enamels on a small object at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. This object dates to the ninth century and was created in the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire whose capital was Constantinople (modern Istanbul). But this is not merely an image meant to be displayed; it is also a box, which was designed to contain a piece of the True Cross on which Christ himself was believed to have been crucified.

As in other religious traditions, Byzantine Christians believed in the spiritual power of relics, that is, the physical remains of holy people or places, and objects closely associated with them.

With the ability to heal and protect, relics were kissed, carried in processions, or worn close to the body, and they were often kept in special containers that we call reliquaries. While on their most basic level reliquaries were designed to protect and display their precious contents, their visual characteristics often exceeded this function and could play a crucial role in expressing and mediating the meaning of relics for their viewers.

Such is the case with the Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke (“cross container”), named after two of its previous owners, Sinibaldo Fieschi and J. Pierpont Morgan (more on that below). Although empty now, it likely once contained a fragment of the wood cross upon which Jesus of Nazareth is believed to have been crucified—one of the holiest relics in the Christian tradition.

According to legend, the True Cross was miraculously discovered in Jerusalem by empress Helena (who probably lived c. 250/257–330/336 C.E.), the mother of emperor Constantine I. While substantial pieces of the wood were said to have been sent to Constantinople, initially most of the cross remained in Jerusalem where it was kept at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and displayed for veneration on special days. Egeria, a western European pilgrim who visited the Holy Land between 381–384, described the veneration of the cross in Jerusalem on the Friday before Easter. The relic was brought out in a gold and silver reliquary, then taken out and placed on a table so that people could approach and kiss it, one by one, while the bishop and deacons guarded it carefully. While people did not touch the wood with their hands, Egeria reports:

On one occasion (I don’t know when) one of them bit off a piece of the holy Wood and and stole it away, and for this reason the deacons stand around and keep watch in case anyone dares to do the same again.” Egeria 37.1-2

Egeria’s account dramatically illustrates the power of relics and the desire many Christians felt for them.

By the end of the fourth century, smaller fragments of the True Cross were circulating throughout the Byzantine Empire and continued to spread within its borders and beyond. Often given as imperial or high-status gifts, new reliquaries were made to hold the relics, which were believed to provide protection for their owners. The small size of the Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke suggests that it was intended for private devotional use.

The box is made of precious materials that befit the holy contents. Saintly figures fill sections of its lid and sides. The smooth surfaces and strikingly rich, luminous colors of the exterior are features of the cloisonné enamel technique, of which this is one of the earliest Byzantine examples. Derived from the French term cloison (“partition”), cloisonné enamel was made by outlining the shapes of figures and other forms in thin, flat strips of gold, which were then soldered to a gold ground. The artist filled these outlined shapes with ground glass in different colors and then fired the ensemble, which fused the glass and gold. After it cooled, the hardened surface was polished. In the final result gold elements reflect light through translucent fired glass, achieving a gem-like visual effect.

Upon closer inspection of the enameled forms on the staurotheke, we can see that Greek inscriptions—also made of soldered strips of gold—identify the figures. A total of twenty-seven saints on the lid and four sides frame a central image of the Crucifixion, which was a standard narrative subject in Byzantine art inspired by Jesus’ life. Christ is shown on the cross flanked by Mary, his mother, and John, one of his disciples. On either side of Christ’s head is inscribed “Here is your son … Here is your mother,” a reference to John 19:26–27 when Christ addresses Mary and John from the cross.

Each figure also has an identifying inscription, and Mary’s is particularly interesting. She is labelled Theotokos (“God bearer”), a title for the Mother of God that helps date this object to the early ninth century, when fierce debates concerning the use of religious images—known as the Iconoclastic Controversy—were underway in Byzantium. Scholars believe the use of this term in religious art at this time reflects Mary’s important role in Christ’s incarnation, which played a pivotal role in theological arguments in favor of icons, since it was Christ’s birth as a physical, visible human being that enabled him to be depicted by artists. [1]

The reliquary’s exterior imagery begins to explain the significance of the relic inside and how it fits into the Christian story of salvation. The central depiction of the Crucifixion includes several features of the subject’s early iconography: It shows Christ upright on the cross, wearing a long, sleeveless tunic (colobium). His eyes are wide open, meaning that Christ is alive, a detail that emphasizes Christ’s victory over death.

Here we see the cross not only as an instrument of execution but also of salvation, which would have prepared the Byzantine viewer for what lay beneath the enamel lid: a fragment of its wood. Today we only see the empty cruciform cavity where the relic would have been kept, but we can imagine how the act of sliding back the lid would have reinforced connections between the image of Christ on the cross and the True Cross relic underneath it. For viewers opening the staurotheke, the physical presence of the wood fragment confirmed Christ’s salvation of humankind through the Crucifixion.

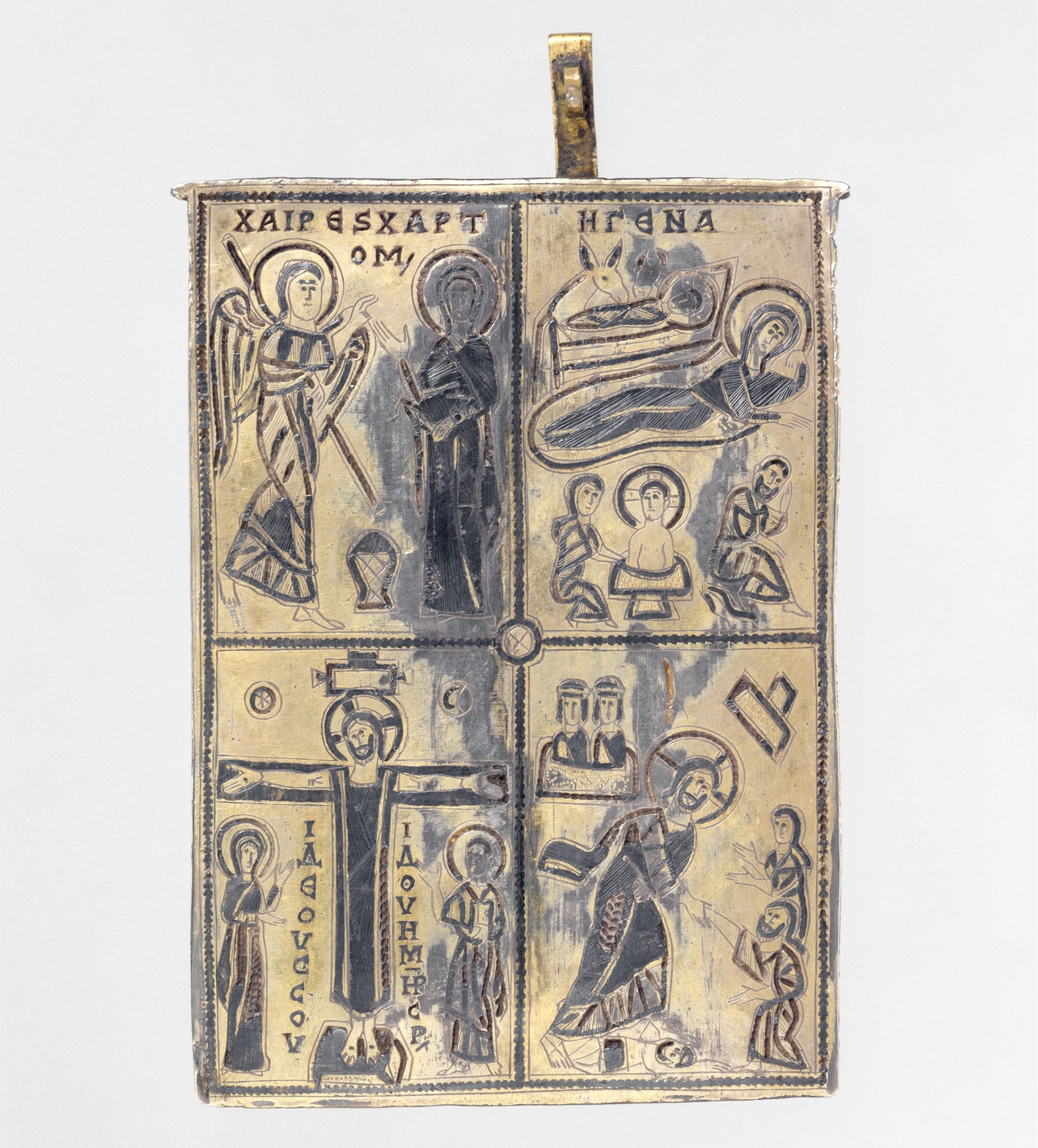

The visual framing of the relic expands when we turn over the lid, where additional images focus on Christ’s incarnation and resurrection: The Annunciation, the Nativity, the Crucifixion, and the Anastasis (Resurrection). These four scenes, which were rendered in a different medium, niello on silver (an engraving technique where lines incised into metal are darkened with a black sulfuric compound), would have been visible only to viewers who removed the lid and flipped it over. The four scenes show Christ’s incarnation, birth, death, and descent into hell to raise the dead (the result of Christ’s own triumphant death on the cross and subsequent resurrection). In the context of personal devotion, the private experience of opening the reliquary and witnessing its unfolding sequence of images and relics in full would have invited viewers to contemplate the mysteries of salvation, and their own hope for resurrection.

The Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke was probably made in Constantinople, but its small size made it easily portable. Its original owner is unknown, but by the mid-thirteenth century it had been brought to Rome and was in the collection of pope Innocent IV (pope from 1243–54), born Sinibaldo Fieschi. During this period, many sacred relics and artworks were brought from Constantinople to western Europe, a result of the occupation of the city in 1204 by crusaders who exiled the Byzantine emperor and established a Latin Kingdom that lasted until 1261. The reliquary remained in the possession of the Fieschi family until 1887, when it was sold to another collector, before the American financier and collector J. Pierpont Morgan finally purchased it in 1906. After his death in 1913, the reliquary was among a large 1917 donation of Morgan’s art to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Today, the Fieschi Morgan Staurotheke continues to travel to major exhibitions as a key witness to the Byzantine devotion to relics and the techniques and iconography of Byzantine art.

Notes:

[1] Brandie Ratliff, cat. no 54, “Reliquary of the True Cross (Staurotheke),” in Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, 7th-9th c., edited by Helen C. Evans and Brandie Ratliff (New Haven and London, 2012), 88-89. For more on the place of Mary in the theological debates, see Niki Tsironis, “The Mother of God in the Iconoclastic Controversy,” in Mother of God: Representations of the Virgin in Byzantine Art, edited by Maria Vassilaki (Milan, Athens, and New York, 2000), 27-39.

Additional Resources

See this object on The Metropolitan Museum of Art website

<https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/472562>

<https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/relc/hd_ relc.htm>

Robin Cormack, Byzantine Art (Oxford and New York, 2000), 102-104, fig. 65

<https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_Glory_of_Byzantium_Art _and_Culture_of_the_Middle_Byzantine_Era_AD_843_1261>

<https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Byzantium_and_Islam_Age_of_ Transition?Tag=&title=byzantium%20islam&author=&pt=0&tc=0&dept=0&fmt=0>

Anna Kartonis, Anastasis: The Making of an Image (Princeton, 1986), esp. 94-125

Annie Montgomery Labatt, “The Transmission of Images in the Mediterranean,” in The Age of Transition: Byzantine Culture in the Islamic World, edited by Helen C. Evans (New Haven and London, 2012), 70-81, figs. 1 and 2

John Lowden, Early Christian and Byzantine Art (London, 1997), 169-174, fig. 98

John Wilkinson, Egeria’s Travels, 3rd edition (Warminster, England, 1999)