20

Dr. Robert G. Ousterhout

The “Transitional Period”

The “Transitional Period” of Byzantine history, corresponding to the Iconoclast controversy (a dispute over the use of religious images, or “icons,” in the eighth and ninth centuries), incursions by the Arabs (in the seventh and eighth centuries), and an economic downturn, was not conducive to architectural production and, it seems, less conducive to the documentation of building activity. The period nevertheless accounts for dramatic and permanent changes in Byzantine religious architecture in both form and scale.

The lack of secure criteria for dating the surviving buildings has long plagued Byzantine scholarship. An earlier generation of scholars familiar with the architectural program of emperor Basil I (reigned 867–86) from the Vita Basilii, an anonymous biography, viewed his reign as a formative period and consequently dated a variety of “transitional” churches in Constantinople (the capital of the Byzantine Empire) to the ninth century. None of buildings mentioned in the Vita survives, however, nor any other of the great monuments of ninth-century Constantinople. The palaces of Theophilos (reigned 829–42) described in historical sources have similarly vanished without a trace, and only paltry foundations remain for the well-documented monasteries on the Princes’ Islands (nine islands southeast of Constantinople in the Sea of Marmara).

Shrinking churches

This period of economic downturn and loss of territory led to a decrease in pan-Mediterranean trade, a reduction in the size of cities, and a social and economic shift from urban to rural. Public ceremonies, which often incorporated the emperor and church officials—a hallmark of previous centuries—also declined, and the Byzantine liturgy became more interior, with fewer outdoor processions. Churches became smaller and more centralized, accommodating smaller congrega- tions and a more static liturgy. In general, the decrease in the scale of church construction led to the development of new, simpler architectural designs.

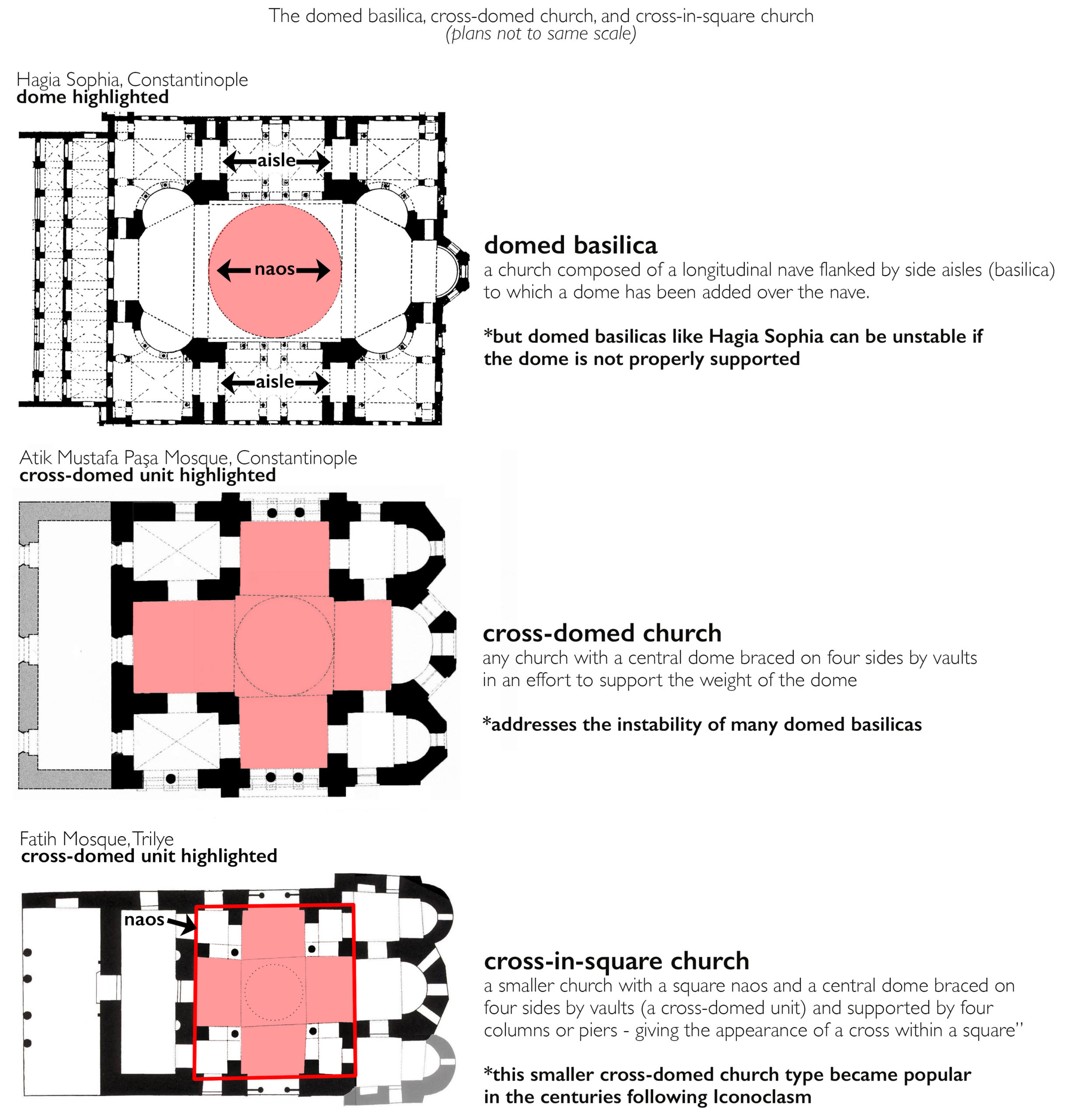

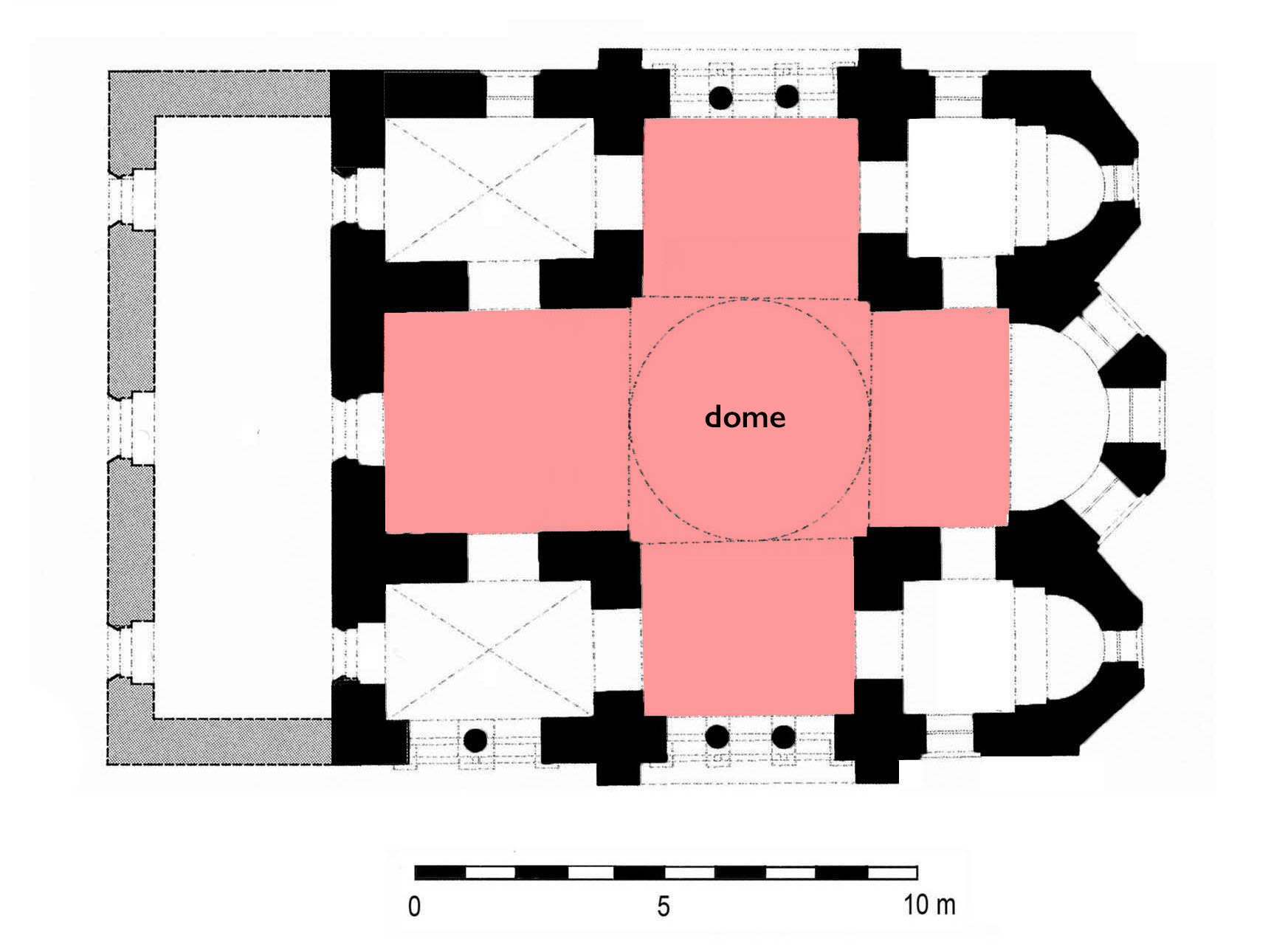

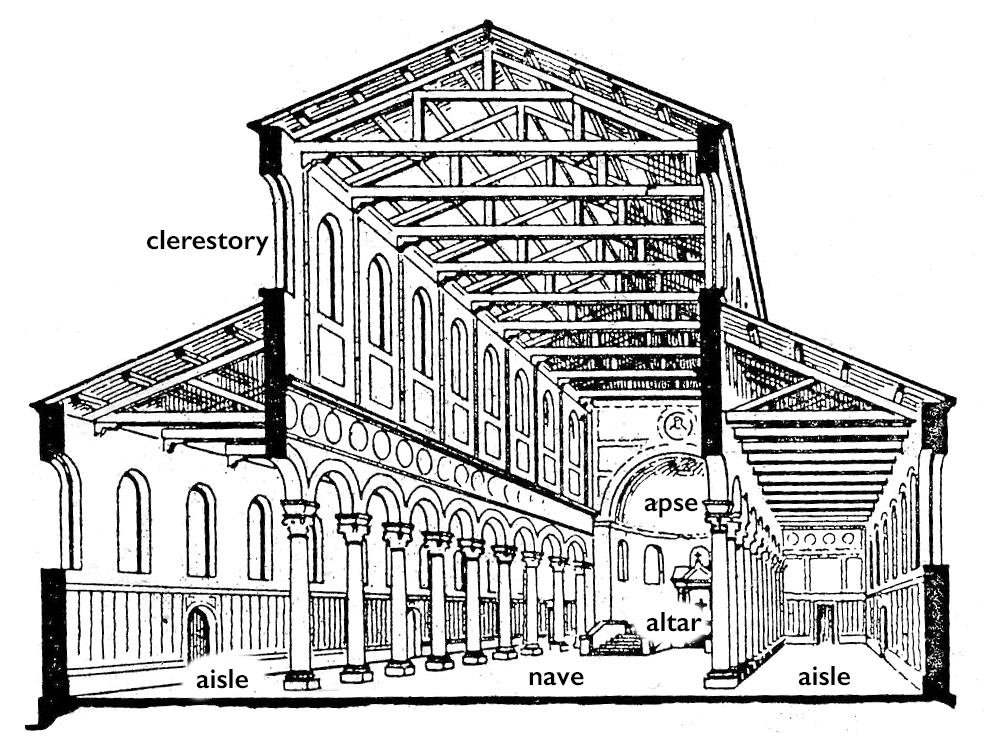

As we might expect, given the importance of Hagia Sophia, domed churches predominate —following a simplified version of the grand developments of the age of Justinian. As a domed basilica (a basilica to which a dome has been added over the nave), the sixth-century H. Sophia Constantinople had a dome diameter of 100 Byzantine feet (the Byzantine foot, or pous, was approximately 31.23 cm, or 1.02 ft). In contrast, the dome of the early tenth-century Myrelaion in Constantinople, a cross-in-square church, was barely one-tenth of that. A cross-in-square church is a church with a square naos and a central dome braced on four sides by vaults and supported by four columns or piers—giving the appearance of a cross within a square.

From a practical point of view, churches of different scales demanded different structural systems. For smaller churches, galleries (the upper level in a church) and ambulatories (a passage around a central space) were unnecessary and internal supports could be reduced to columns. The domed basilica provided sufficient space for a larger congregation. The cross-domed church offered an effective structural design for an intermediate congregation. The cross-in-square was ideal for smaller churches with a dome fewer than 20 Byzantine feet in diameter. It was this smaller church type that became popular in the centuries following iconoclasm.

Refining old designs

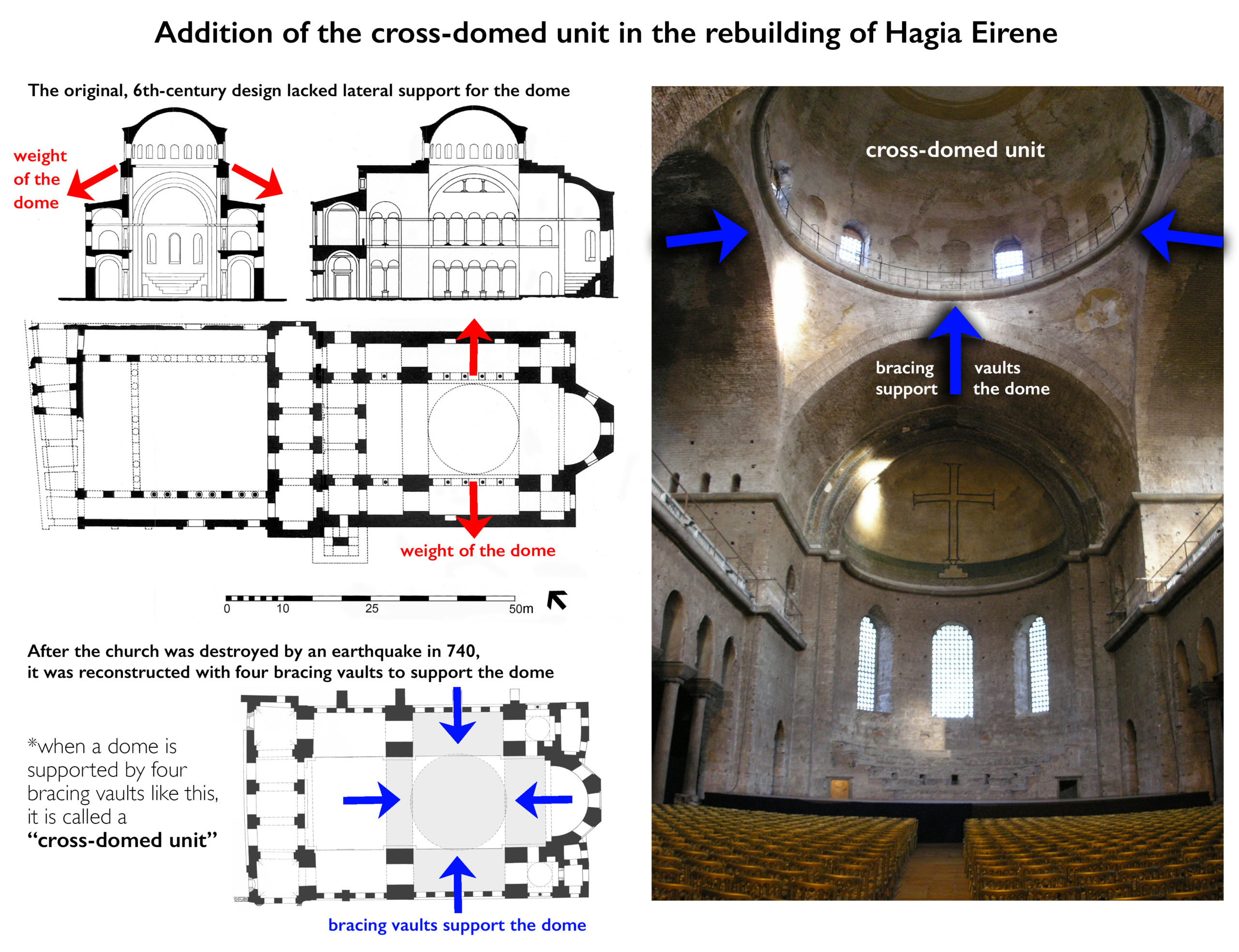

Critical in the development may be the reconstruction of Hagia Eirene in Constantinople (Istanbul), destroyed in the earthquake of 740 and rebuilt later in the century. While retaining the domed basilica plan, it corrected the basic structural problem of its predecessor (inadequate lateral support for its dome) by adding transversal barrel vaults over the galleries so that the dome was evenly braced on all four sides, usually referred to as a cross-domed unit (a structural unit comprising a central dome braced on four sides by vaults).

This bilaterally symmetrical system appears at the core of a variety of smaller buildings with cruciform plans, such as at the church now known as the Atik Mustafa Paşa Mosque in Istanbul, probably constructed in the ninth century.

Many churches appear as the reconstruction or reconfiguration of older buildings; rather than representing a new theoretical model, they express the very real concerns of a society in transition. In many examples, we find the reduction in scale of an Early Christian basilica into a new church constructed on the same foundations, reemploying many of the same architectural elements, with its basic design is transformed. Indeed, H. Eirene in Constantinople is still most often discussed as a Justinianic building (the term “Justinianic” refers to the reign of emperor Justinian I who reigned from 527–65), although almost all of its superstructure—and its reformulated structural system—belong to the eighth century. (The superstructure of a building comprises the parts built above ground level, which are supported by the underlying substructure.)

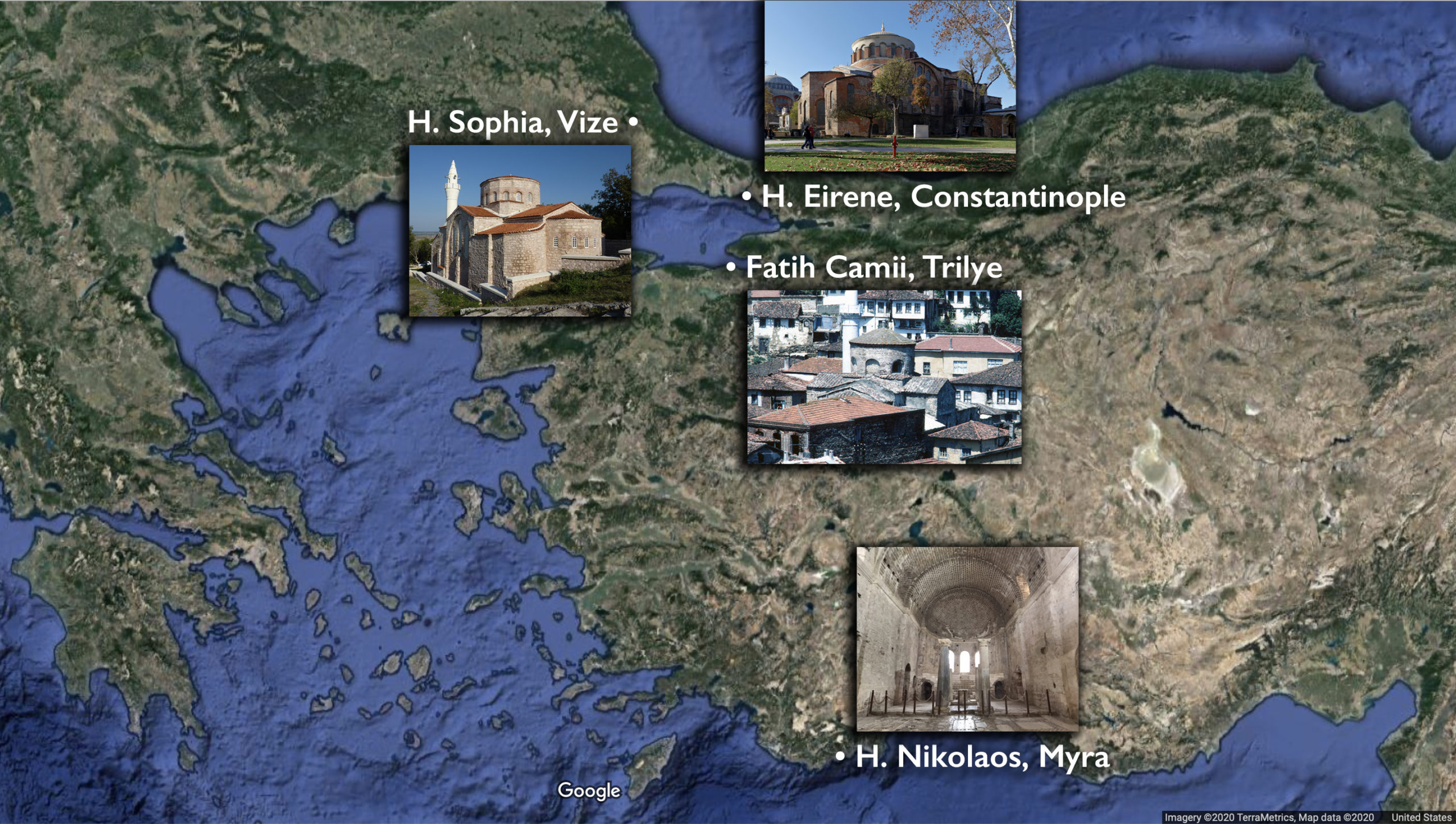

H. Nikolaos, Myra (Demre)

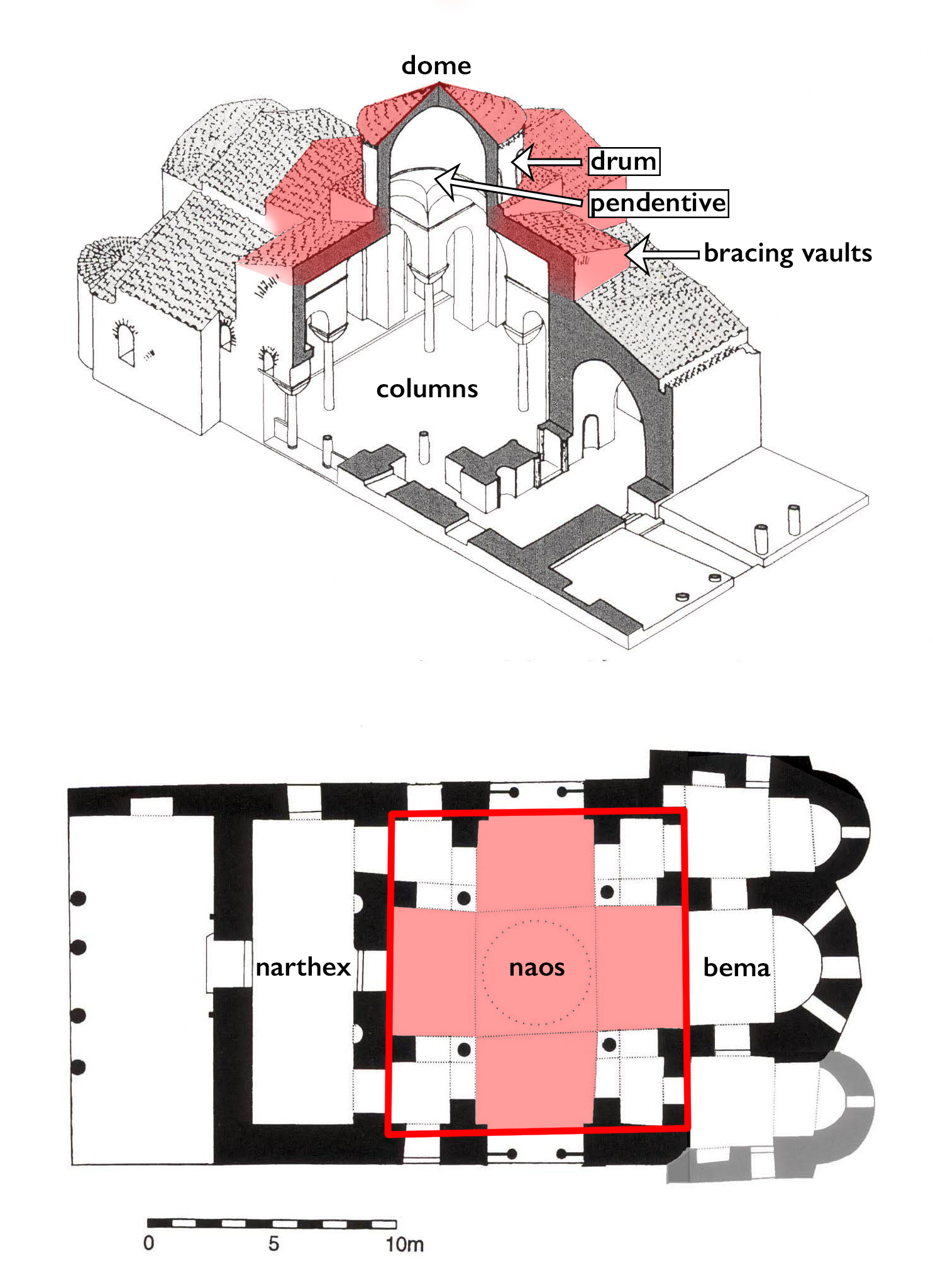

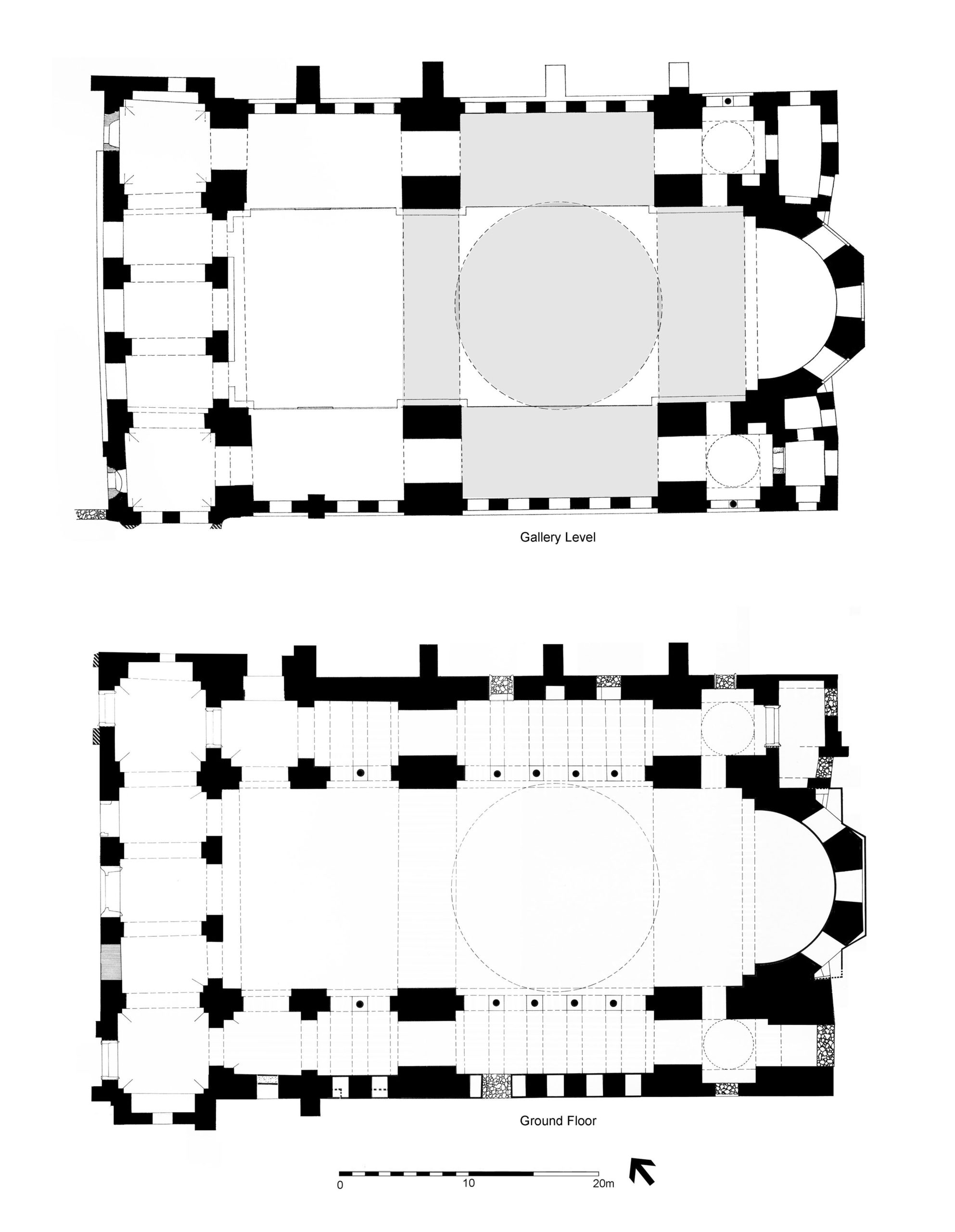

Similarly, H. Nikolaos at Myra (in southern Turkey) was rebuilt in the eighth century as a domed basilica on the foundations of its Early Christian predecessor. Elements of the older building are incorporated in the atrium (the forecourt of a church, usually surrounded by porticoes) and south chapels. The naos (the main space of a centrally planned church), with a dome of c. 7.70 m diameter (replaced by a groin vault in the 19th-century renovation), was extended to the east and west by narrow barrel vaults (a type of ceiling that forms a half cylinder) and enveloped by lateral aisles and a narthex (the entry vestibule preceding the nave or naos) on the ground floor, with galleries above. The church also included a second aisle to the south with arcosolia (an arched burial niche), although it remains unclear which tomb belonged to Nikolaos. Additional constructions of later centuries expanded the building on all sides.

Hagia Sophia in Vize

Hagia Sophia in Vize (now Süleyman Paşa Mosque, photo below) is similar in design and may be dated sometime after 833. It seems likely that this was the episcopal church of Bizye, associated with events mentioned in the vita of St. Mary the Younger, a Byzantine saint of Armenian origin who died c. 902. Like Hagia Nikolaos, it reused the foundation of an older basilica. Rebuilt as a domed basilica, its plan is basilican on the ground level, while the gallery includes a cross-domed unit, like that of Hagia Eirene, with transverse barrel vaults extending over the galleries to brace a dome c. 6 m. in diameter, raised above a windowed drum (the cylindrical structure on which a dome is raised).

Cross-in-square churches

Fatih Mosque (H. Stephanos ?), Trilye in Bithynia

The cross-in-square or four-column church type seems to have been developed in this period as well, as is well preserved in the early ninth-century Fatih Mosque (H. Stephanos?) in Trilye in Bithynia (east of Constantinople/Istanbul).

As is repeated in any number of later versions, the central dome (with a diameter of 15 Byzantine feet at Trilye) is raised on a cylindrical drum above pendentives, supported on four columns above a squarish naos. A tripartite sanctuary, partially preserved, extends to the east—the bema (where the altar was located) now a separate space from the naos—balanced by a narthex to the west. Although architectural developments in this difficult period may be credited to the rise of monasticism, notably in Bithynia, beyond individual churches, there are not surviving remains.

Additional Resource

Robert G. Ousterhout, Eastern Medieval Architecture: The Building Traditions of Byzantium and Neighboring Lands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).