25

Dr. Evan Freeman

Who was the artwork’s patron? What were the artwork’s original meanings and functions? When art historians study a work of art, they ask questions about the artwork’s initial creation. But often, works of art and architecture change over time, challenging us to take a longer view of an artwork’s history and position within social networks, something anthropologist Arjun Appadurai referred to as the “social life” of a thing. [1]

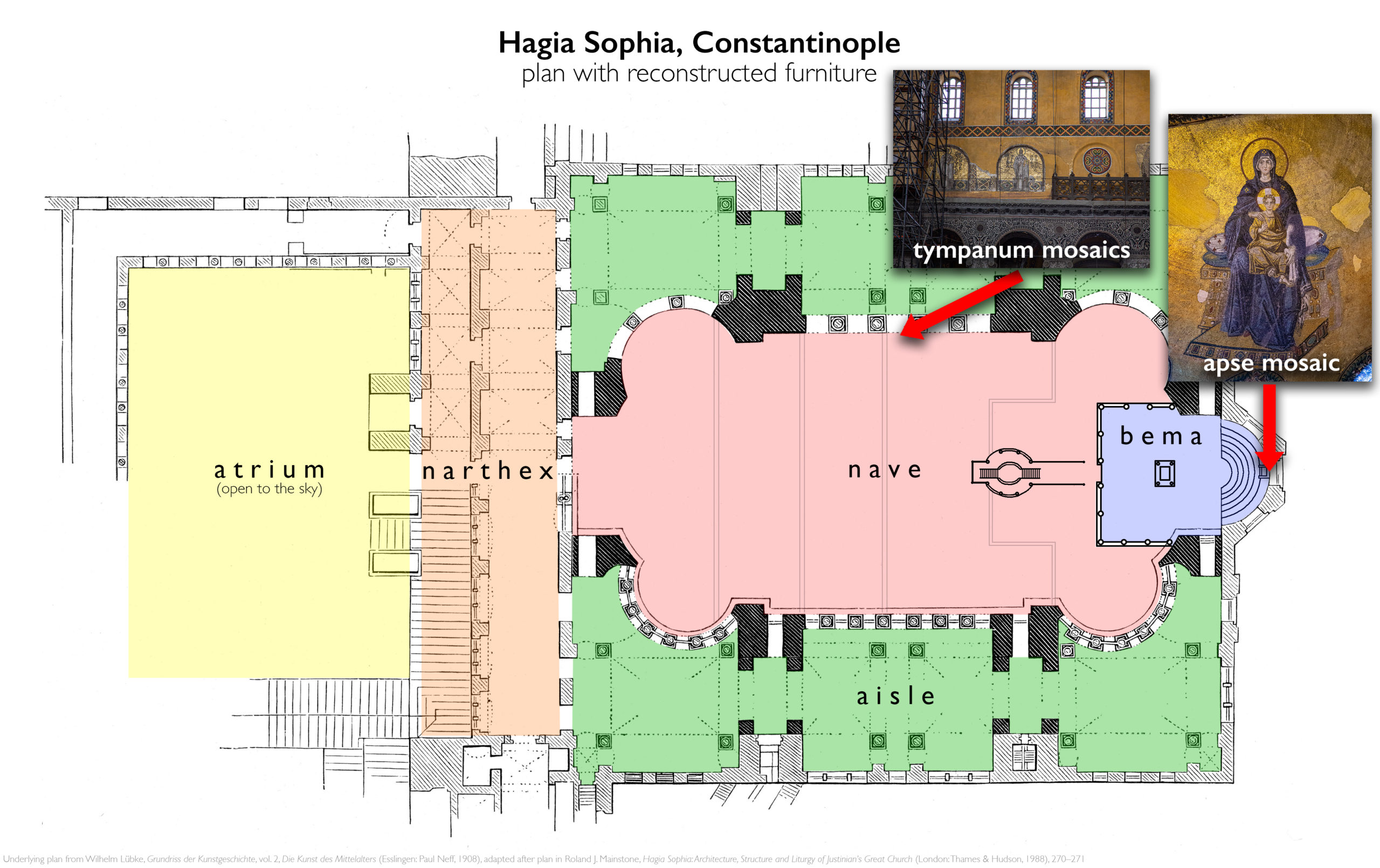

This is the case with the Byzantine church of Hagia Sophia—the main cathedral in Constantinople (modern Istanbul)—which the Byzantines often referred to as the “Great Church.” Built by emperor Justinian (reigned 527–65) during the brief period of 532–537, Hagia Sophia was at first primarily decorated with crosses and non-figural motifs. But in subsequent centuries—and particularly following the a ban on religious images (icons) during the Iconoclastic Controversy of the eighth and ninth centuries—several figural mosaics were added to the walls of Hagia Sophia, which dramatically changed the appearance of Justinian’s Great Church. These mosaics illustrate the ways Hagia Sophia became entangled in and responded to theological controversies, imperial donations, and even marriages.

Holy figures

Apse mosaic: Virgin and Child

The first major mosaic added to Hagia Sophia following the 843 end of Iconoclasm depicted the Virgin Mary and Christ Child in the apse, the semidome above the altar at the eastern end of the church. It was accompanied by an inscription that alluded to Iconoclasm: “The images which the imposters [i.e. the iconoclasts] had cast down here pious emperors have again set up.” The mosaic was probably completed around 867, when patriarch Photios, the leader of the Church in Constantinople, preached a sermon that also interpreted this image in terms of the end of Iconoclasm. The location of this Virgin and Child mosaic—which visualized Christ’s incarnation (becoming flesh and blood)—was also significant since the Byzantines believed that the Eucharistic bread and wine similarly became Christ’s flesh and blood on the altar below.

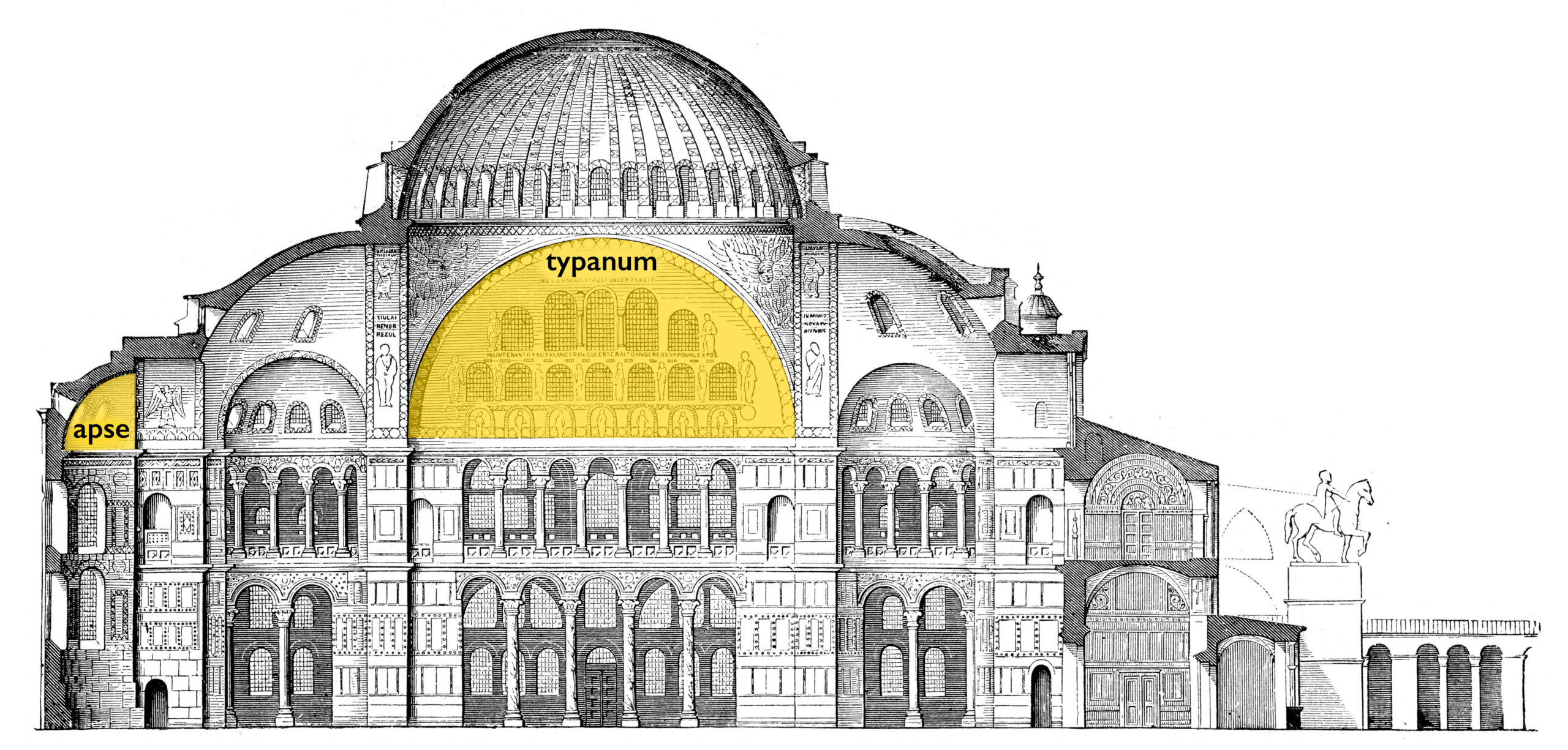

Tympana mosaics

Not long after the apse mosaic was installed, additional mosaics were added high on Hagia Sophia’s north and south walls, in the tympana beneath the central dome, toward the end of the ninth century.

These depicted rows of holy figures—Church fathers on the bottom, prophets in the middle, and probably angels above—though only a few of these mosaics survive today. Strikingly, recent patriarchs such as Ignatius the Younger (who died in 877) are pictured among Church fathers in the tympana, likely because of their defense of images during Iconoclasm, as well as their association with Hagia Sophia.

Emperors and ceremony

But not all of the images in Hagia Sophia were purely religious in their subject matter. Several mosaics featured images of emperors and empresses: some long dead and others still living at the time when the mosaics were installed. Such images remind us that over the long history of the Byzantine Empire, there was no separation of Church and state. The emperor often participated in Church rituals with the clergy in Hagia Sophia.

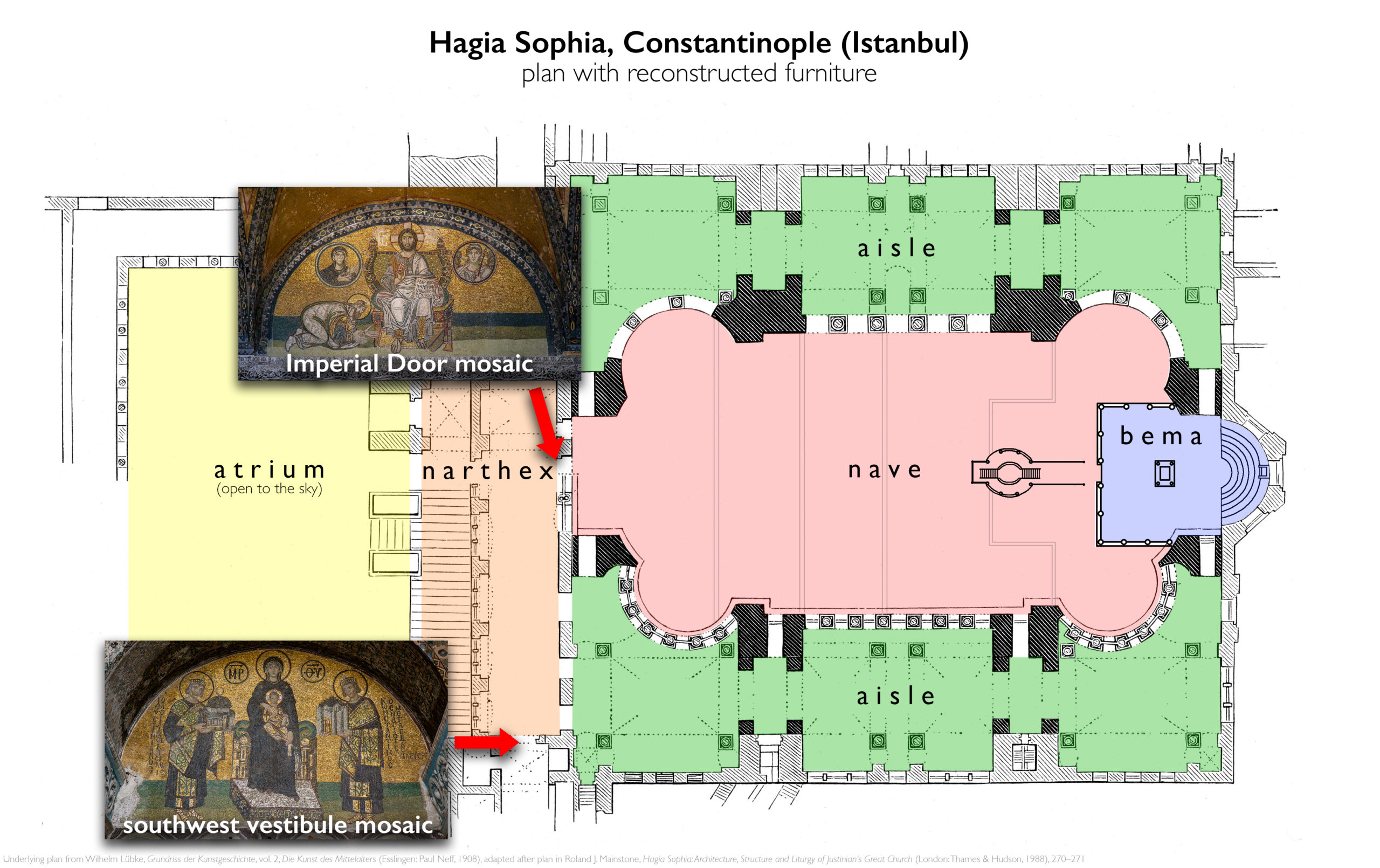

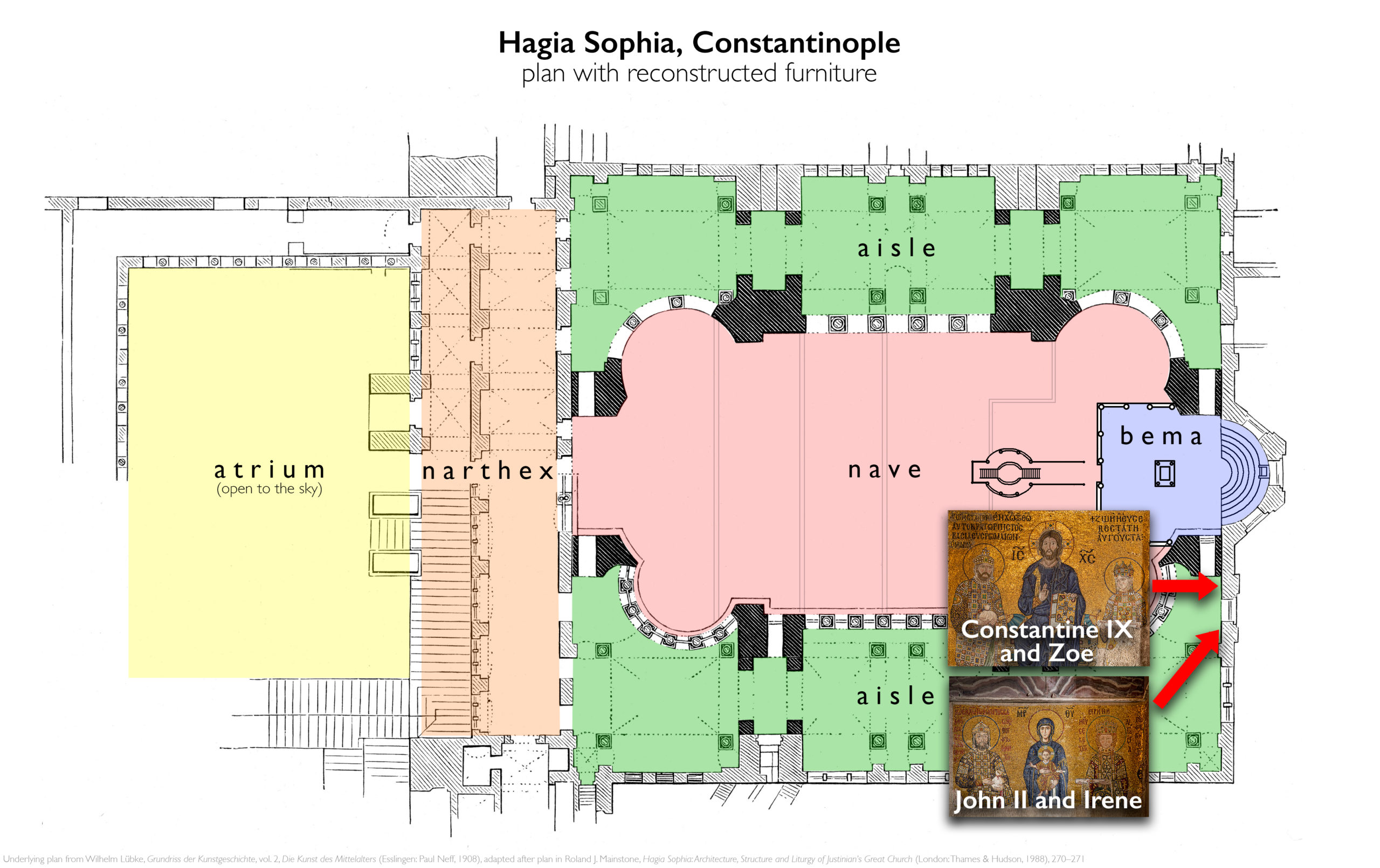

Two mosaics depicting emperors were positioned along a ceremonial route by which the emperor sometimes entered Hagia Sophia for the celebration of the Divine Liturgy, as described in the tenth-century Book of Ceremonies. (The Divine Liturgy is a service of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which, like the Roman Catholic Mass, includes hymnography, readings from the Bible, and the celebration of the Eucharist.)

Southwest vestibule

As they entered the narthex of Hagia Sophia, living emperors would have passed under a mosaic of great emperors from centuries past. This mosaic appears in a lunette (a semicircular architectural space) in the southwest vestibule and was likely installed in the early tenth century.

A towering image of the Virgin appears at the center, flanked by large letters identifying her as the “Mother of God.” She holds the Christ Child on her lap and sits on a lavish throne, resting her feet on a jeweled footstool. This central image of the Virgin and Child is similar to the ninth-century image in Hagia Sophia’s apse discussed above, which the emperor would encounter as he continued into the church.

On the right, emperor Constantine, who founded Constantinople in 330 C.E., offers a model of the city (with its high crenelated walls) to the Virgin and Child. On the left, emperor Justinian, who built Hagia Sophia between 532–37, offers a domed model of Hagia Sophia—the very church in which this mosaic is located—to the Virgin and Child. Images showing donors offering smaller models of the buildings they had built to heavenly figures were common in medieval art. Both emperors wear the imperial loros, a rich sash-like garment that was often decorated with precious stones. The mosaic highlights the Byzantine understanding of the Virgin as protector of Constantinople, as well as the importance of imperial patronage.

Imperial Door

As the emperor continued his ceremonial entrance into Hagia Sophia, he proceeded into the main part of the church through the “Imperial Door,” the central door between the inner narthex and the nave. A mosaic dated to around 900 (probably slightly earlier than the mosaic in the southwest vestibule) appears in the lunette above the Imperial Door. In this mosaic, a frontal Christ sits formally on a lyre-backed throne. The “lyre-backed” throne, named for its resemblance to the ancient musical instrument, appears in Early and Middle Byzantine art and may have been associated with a mosaic image of Christ in the Chrysotriklinos (main throne room) in the Great Palace of Constantinople. Christ blesses the viewer with his right hand and rests an open book on his left knee, which displays the text: “Peace be with you; I am the light of the world” (a paraphrase of John 20:19 and John 8:12). Two roundels flank Christ.

An angel appears within the roundel on Christ’s left. On his right, a woman who is probably the Virgin Mary extends her hands toward Christ in a gesture of supplication.

Below the Virgin, an unnamed emperor with similarly outstretched hands bows before Christ in a gesture of reverence known as proskynesis. Who is this emperor? Several theories have been proposed. Some have understood the emperor as Leo VI atoning for marrying four times— considered a sin and even illegal—in pursuit of a male heir. More recently, scholars have questioned whether this mosaic even represents a specific, historical ruler, or whether it is a more generalized representation of imperial submission to Christ. This image certainly would have been meaningful when emperors performed their own acts of proskynesis here in the narthex (as described in the Book of Ceremonies) before passing beneath this mosaic to enter the nave of the church.

Imperial patrons

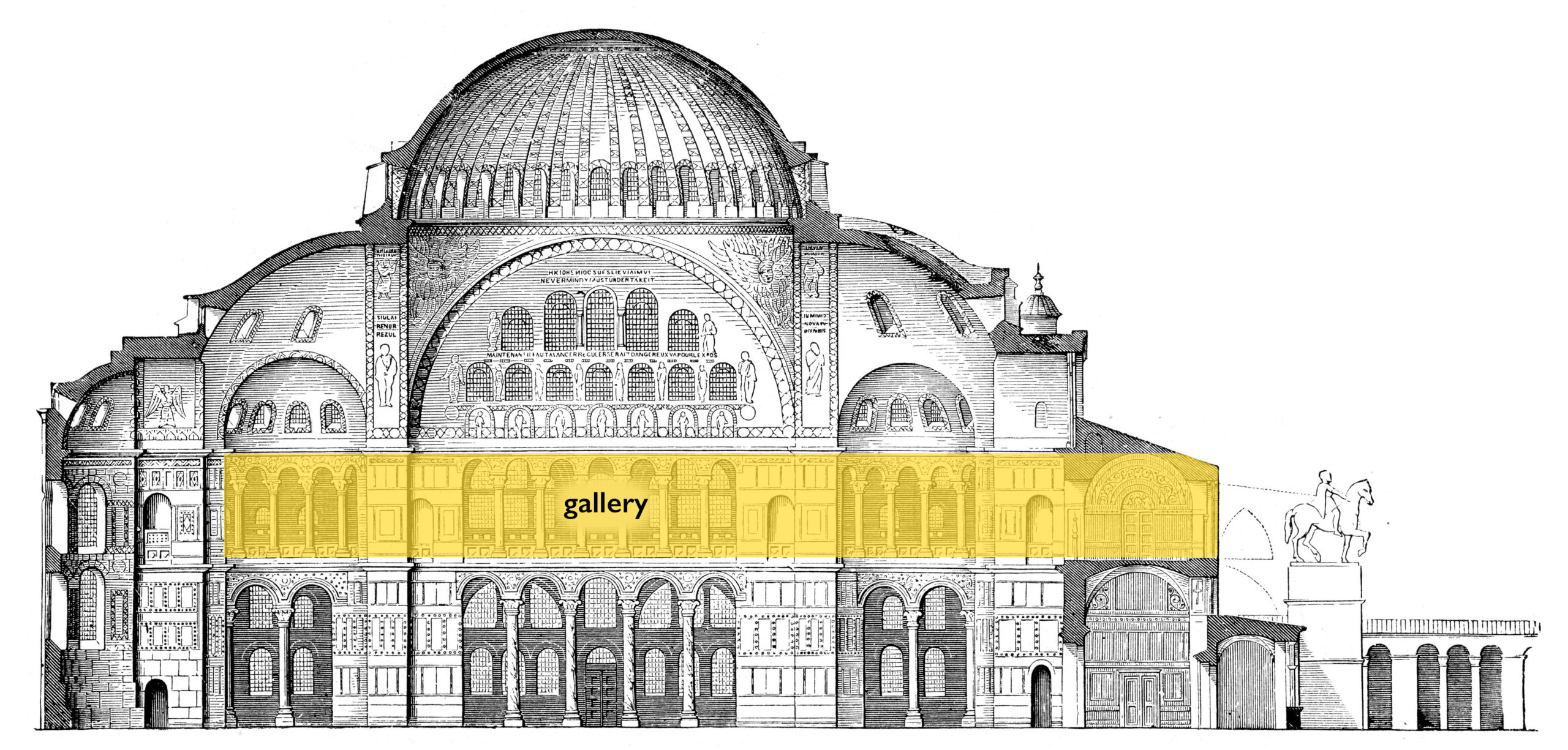

Two additional mosaics were added to Hagia Sophia in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Their subjects and location are closely related. Both depict emperors and empresses and are located in the south gallery (on the second level, above the south aisle)—which was traditionally reserved for imperial use during church services—near a doorway that connected Hagia Sophia with the Great Palace.

Constantine IX and Zoe with Christ

In the first mosaic, added during the waning years of the Macedonian dynasty (which ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056), Christ appears enthroned at the center, flanked by an emperor and empress. When it was first installed between 1028–34, this mosaic probably depicted empress Zoe and her first husband, Romanos III, who reigned 1028–34. (Empress Zoe, second daughter of Constantine VIII, reigned with Romanos III 1028–34, with Michael IV 1034–41, and with Constantine IX Monomachos from 1042 until her death in 1050.) The mosaic would have commemorated an imperial donation to Hagia Sophia, when the capitals of the Great Church were gilded. But the mosaic was subsequently altered between 1042–55, replacing Romanos III with Zoe’s third husband, Constantine IX Monomachos (who was also a patron of Nea Moni on Chios, known for its lavish mosaic decoration).

This revised version of the mosaic, which survives today, probably commemorated another imperial donation to the Hagia Sophia, one which enabled the Divine Liturgy to be celebrated in the Great Church every day rather than only on weekends (the cost of putting on a service in Hagia Sophia—including paying the large number of clergy and staff—was considerable). Constantine IX and Zoe turn inward toward Christ, offering a bag of money and what is probably a contract of donation. This image illustrates how such donations to the Church were understood as offerings to God.

Curiously, when the identity of the emperor was updated, Zoe and Christ were also given new faces. Perhaps the goal was to give all three faces a consistent stylistic appearance. Another theory suggests that Zoe’s original face may have been destroyed as an act of damnatio memoriae (the official erasure of someone’s legacy) when Zoe was briefly exiled before her third marriage, and therefore needed to be replaced.

John II and Irene

A similar imperial mosaic was installed c. 1118–34 beside the image of Constantine and Zoe in the south gallery. It is the only surviving mosaic from twelfth-century Constantinople. The Virgin and Child appear at the center (complimenting the nearby image of Christ). On either side, emperor John II of the Komnenian dynasty and empress Irene occupy the same positions as Constantine IX and Zoe in the earlier mosaic, similarly offering a money bag and a rolled document. (The Komnenian Dynasty ruled the Byzantine Empire 1081–85; Emperor John II Komnenos reigned 1118–43; Empress Irene of Hungary married John II Komnenos in 1104 and reigned with him from 1118 until her death in 1134.)

These emperors and empresses in the south gallery all appear shorter than the important central figures of Christ and the Virgin whom they flank. At the same time, the closeness of these haloed emperors and empresses to Christ and the Virgin suggests the considerable power of these Byzantine rulers, who immortalized themselves in fields of gold on the walls of Constantinople’s Great Church.

A work in progress

Although Justinian finished building Hagia Sophia and dedicated it in the year 537, Constantinople’s Great Church was, in a sense, an ongoing work in progress, since subsequent rulers continued to decorate it through the following centuries. When Constantinople was sacked by crusaders in 1204 and subsequently reclaimed by the Byzantines in 1261, Hagia Sophia was again refurbished, and a new mosaic showing the Deësis—an image of intercession and divine mercy—was installed in the south gallery. This last major mosaic was added to the Great Church more than seven centuries after Hagia Sophia’s initial construction. The continuous addition of mosaics to Hagia Sophia—reflecting theological controversies, imperial donations, and even remarriages—illustrates how the continual creation, or “social life,” of a monument can often be a complex, ongoing process.

*

Notes:

[1] Arjun Appadurai coined this phrase in his edited volume: The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

Additional resources

Liz James, Mosaics in the Medieval World: From Late Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Cyril Mango, Materials for the Study of the Mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1962).

Cyril Mango, “The Mosaics of Hagia Sophia,” in Hagia Sophia, ed. Heinz Kähler (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1967), pp. 47-60

Cyril Mango and Ernest J. W. Hawkins, “The Apse Mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: Report on Work Carried out in 1964,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 19 (1965), pp. 113, 115–151.

Cyril Mango and Ernest J. W. Hawkins, “The Mosaics of St. Sophia at Istanbul: The Church Fathers in the North Tympanum,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 26 (1972), pp. 1, 3–41.

Robert S. Nelson, Hagia Sophia, 1850–1950: Holy Wisdom Modern Monument (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Natalia Teteriatnikov, Justinianic Mosaics of Hagia Sophia and Their Aftermath (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2017).