26

Dr. Evan Freeman

Ecstatic Motion

The city of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire since its foundation by Constantine in 330 C.E., was roiled by the Iconoclastic Controversy in the 8th and 9th centuries. Emperors, bishops, and many others debated whether images, or “icons,” of God and the saints were holy or heretical. Those in favor of images triumphed in 843. Soon after, a new church was built in Constantinople’s great imperial palace and adorned with rich mosaic icons. The church was dedicated to the Virgin of the Pharos, named with the Greek word for a lighthouse, since a lighthouse stood nearby. Around 864, patriarch Photios of Constantinople—the highest-ranking cleric in the empire—gushed about the church of the Pharos and its glittering mosaics: “It is as if one had entered heaven itself . . . and was illuminated by the beauty in all forms shining all around like so many stars, so is one utterly amazed.” Photios describes how his whirling to view the church produced the impression that the church itself was moving:

It seems that everything is in ecstatic motion, and the church itself is circling round. For the spectator, through his whirling about in all directions and being constantly astir, which he is forced to experience by the variegated spectacle on all sides, imagines that his personal condition is transferred to the object. – Photios of Constantinople, Homily 10

Photios offers us a tantalizing impression of the Pharos church and a sense of how Byzantines viewed mosaics during this period.

Middle Byzantine mosaics

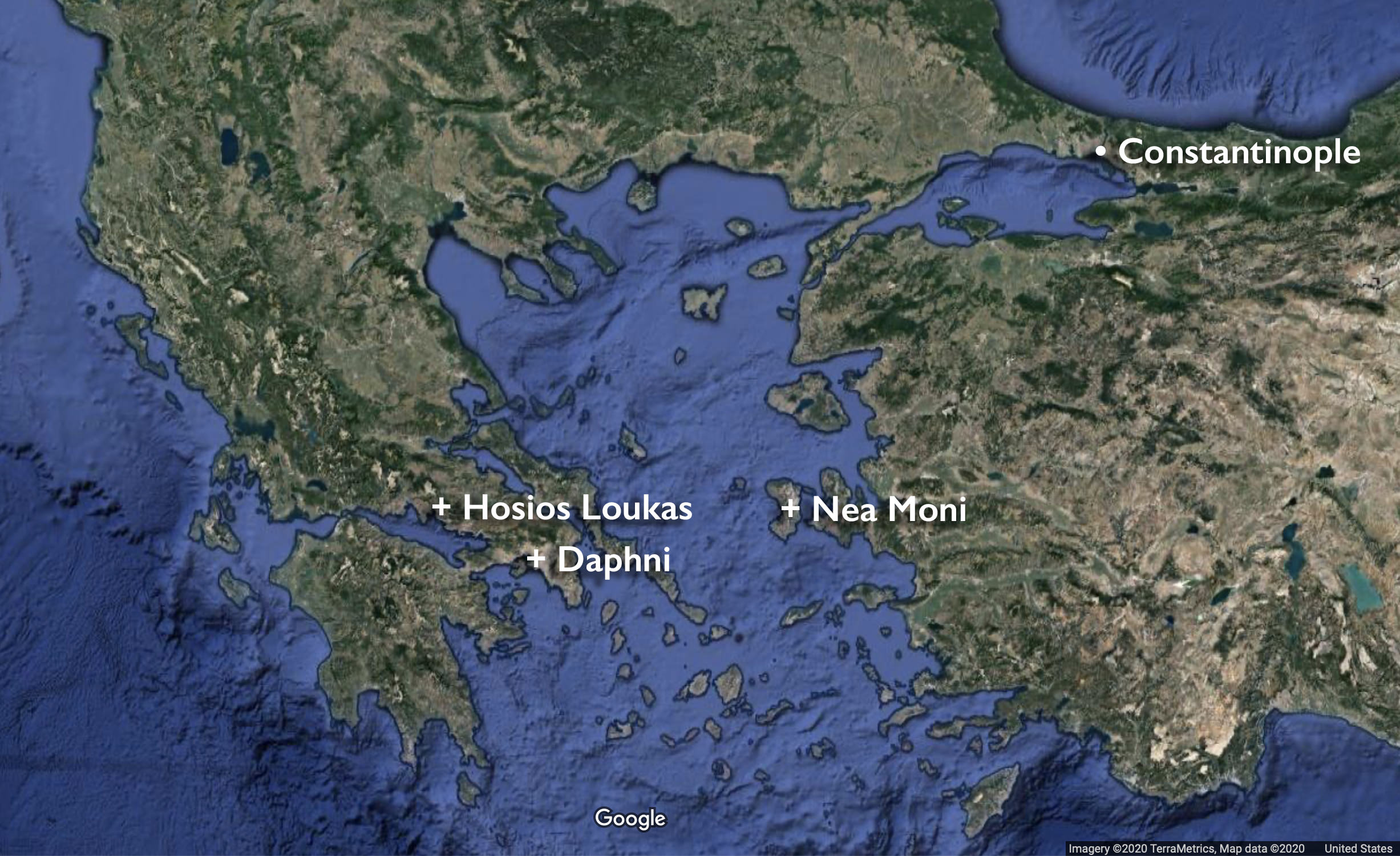

While the church of the Pharos has been lost, three churches from around the eleventh century preserve much of their original mosaic programs, which were likely inspired by churches like the church of the Pharos in the capital. These three monuments—Hosios Loukas, Nea Moni, and Daphni—point to common trends in Middle Byzantine mosaics, while also demonstrating the flexibility of church decoration during this period.

Mosaics are patterns or images made of tesserae: small pieces of stone, glass, or other materials. They commonly adorned floors in antiquity but became popular decoration for church walls and ceilings in Byzantium, especially among wealthy patrons such as emperors.

In the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843–1204), domed, centrally planned churches became more popular than the long, hall-like basilicas of previous centuries. While basilicas created a strong horizontal axis between the entrance on one end and the altar at the other, domed churches added a vertical axis that prompted viewers to look upward. New decorative programs developed in tandem with this architectural trend, covering walls and domes with mosaics and frescos of holy figures in complex, new configurations. The lower portions of churches were often decorated with marble revetment (thin panels of marble, often beautifully colored).

Church as microcosm

Byzantine texts interpreted the domed church as a microcosm—a three-dimensional image of the cosmos—associating the sparkling gold vaults above with the heavens, and the colored marbles below with the earth. Within this framework, images often seem to be arranged hierarchically: with a heavenly Christ reigning above, events from sacred history unfolding below, and portraits of saints surrounding the worshippers in the lowest registers. Many of these images took on additional meanings as church services unfolded.

Spatial icons

The mosaicists who decorated these churches made no effort to create illusionistic backdrops for the holy figures, as one often finds in works from the Italian Renaissance, such as Masaccio’s Holy Trinity fresco. Instead, the holy figures situated in the curves and facets of these Middle Byzantine churches appear against a gold ground. Often, these prophets, saints, and angels seem to face and even communicate with each other across the space of the church. Such “spatial icons”—as the art historian Otto Demus famously described them—created the impression that the holy figures occupied the same physical space as the worshippers.

Hosios Loukas

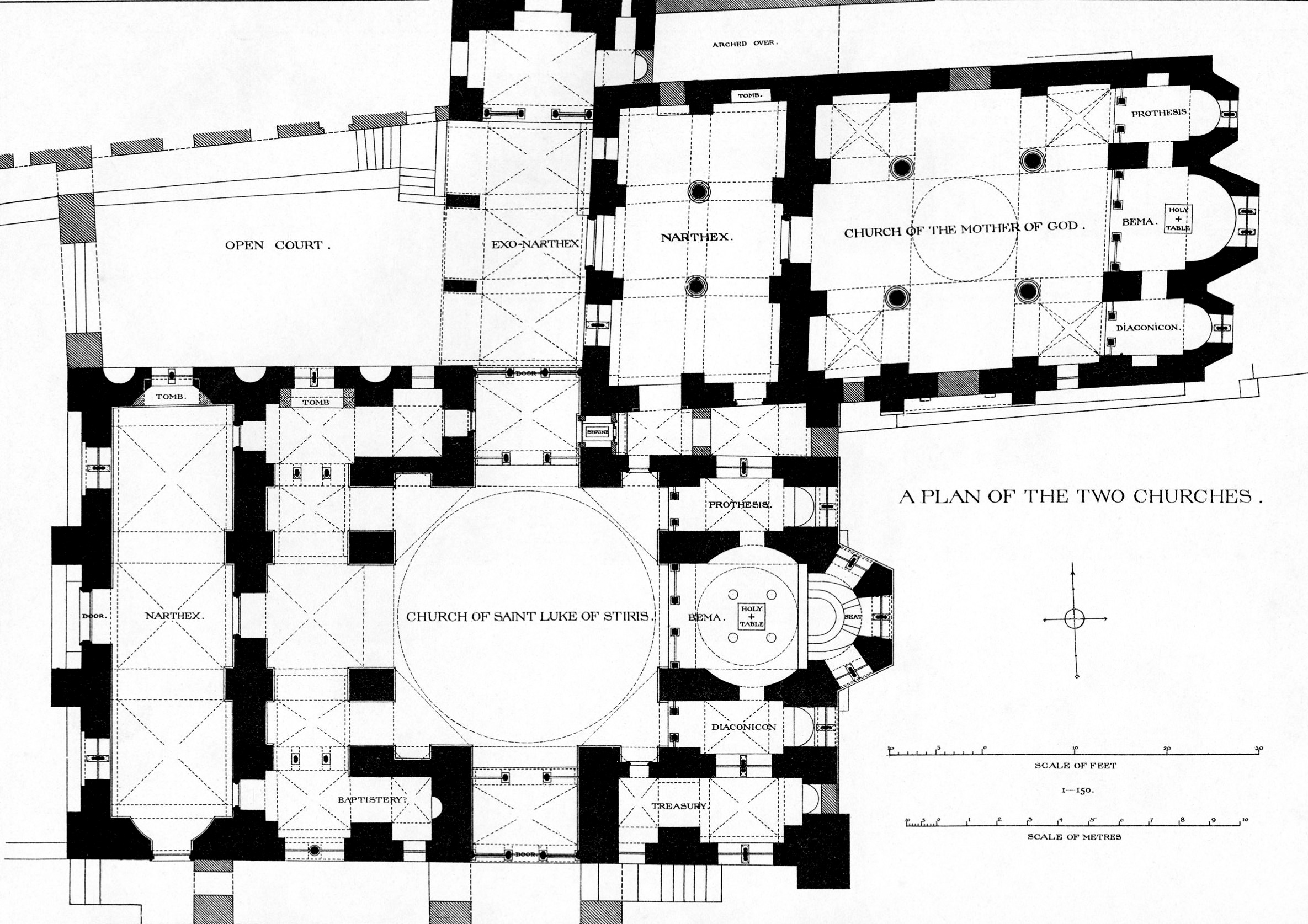

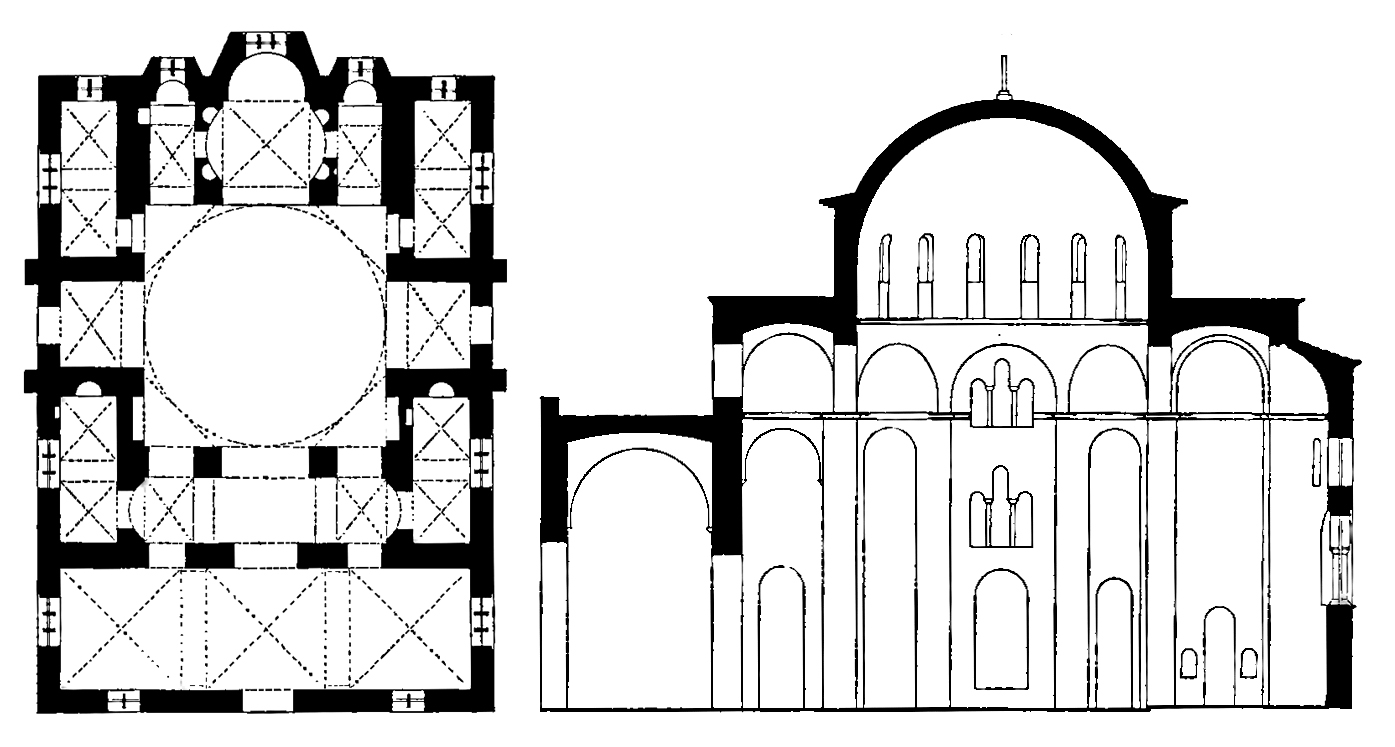

The monastery of Hosios Loukas, located in central Greece, is probably the oldest of the three churches. It is named for St. Loukas of Steiris, a local monastic saint who lived on this site and died in 953. Two connected churches survive here. The older church, dedicated to the Virgin and located to the north, features a cross-in-square plan. (A cross-in-square church is a church with a square naos and a central dome braced on four sides by vaults and supported by four columns or piers – giving the appearance of a cross within a square). The katholikon church (“katholikon” is the modern Greek term for the main church in a monastic complex), built to the south in the eleventh century, utilizes a larger, octagon-domed plan. (An octagon-domed church is a centrally planned church with a dome supported above eight points.) The katholikon church retains many of its mosaics, undoubtedly the result of rich patronage. St. Luke’s body was interred between the two churches, and the monastery attracted pilgrims who sought the saint’s healing.

Worshippers entered the katholikon through the “narthex,” a vestibule at the western end of the building. Here, they encountered portraits of saints and large images of Christ’s Passion (his suffering during Holy Week culminating with the Crucifixion) and Resurrection: Christ washing his disciples’ feet, the Crucifixion, the Anastasis (an image of Christ descending into hades to raise the dead from their tombs), and the incredulous Thomas touching the wounds of the risen Christ.

*

*

Worshippers then passed beneath a large mosaic of Christ Pantokrator (the Byzantines referred to Christ as “Pantokrator,” which means “almighty” or “ruler of the universe”) to enter the main part of the church, or “naos.” Christ displays an open book that proclaims him to be the “light of the world” (John 8:12). The mosaic’s gold tesserae reflect sunlight from the front door in the daytime, and flickering candlelight at night. (In Byzantine mosaics, gold tesserae were not solid gold, but were created by “sandwiching” thin pieces of gold leaf between two pieces of clear glass.)

*

A large fresco of Christ surrounded by angels occupies the heavenly space of the dome in the naos. This fresco may replicate the original dome mosaics, which have been lost. Four squinches (architectural elements used to make the transition from a square space to a circular or polygonal base for a dome) beneath the dome displayed mosaic images from the life of Christ. The Annunciation likely once adorned the northeast squinch but has been lost. The mosaics in the other three squinches depict Christ’s Nativity, Presentation in the Jewish Temple, and Baptism.

Various saints appear below. An abundance of monastic saints— including St. Loukas himself — reflects the building’s function as a monastery church.

Proceeding through the naos, worshippers saw an image of the descent of the Holy Spirit on the apostles at Pentecost in a smaller dome above the altar. The Virgin and Child sit enthroned in the apse behind the altar, a reminder that God became a human being for the salvation of the world. During the Divine Liturgy, this image of Christ’s incarnation took on new significance as the bread and wine also became the body and blood of Christ. (The Divine Liturgy is a service of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which, like the Roman Catholic Mass, includes hymnography, readings from the Bible, and culminates with the celebration of the Eucharist.)

Nea Moni

Hermit monks founded Nea Moni (“new monastery”) on the island of Chios sometime before 1042, and its katholikon was built with the patronage of emperor Constantine IX Monomachos between 1049–55. It features a rectangular plan, and its architectural design may have been adapted to accommodate its mosaic program.

In the narthex, worshippers again encountered an array of saints and large narrative images centering around Christ’s Passion. In the naos, the main dome has lost its mosaics. But remnants of cherubim and seraphim (angelic beings described in the Bible), evangelists, and apostles inhabit pendentives (architectural elements in the shape of a triangular segment of a sphere, used to make the transition from a square room to a circular base) beneath the dome. Further down, eight alternating conches (a half-dome or quarter-sphere vault) and niches (shallow recesses) displayed a ring scenes from the life of Christ. The Virgin appears in the eastern apse behind the altar with hands upraised in prayer, flanked by the archangels Gabriel and Michael.

Daphni

The monastery of Daphni, located just northwest of Athens, was likely the last of the three churches to be built, probably constructed between 1050–1150. Little is known about the foundation of this cross-in-square church.

Here, the narthex combines scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin, suggesting the church may have been dedicated to Mary. Notably, the Last Supper and Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (where she was fed with heavenly bread by an angel) both appear on the eastern wall of the narthex, where worshippers would have seen them as they entered the church. Such images were meant to connect past events from sacred history with the celebration of the Eucharist in the present: Christ sharing bread and wine with his apostles at the Last Supper and Virgin eating heavenly bread in the temple were both understood to prefigure and symbolize the Eucharist. The appearance of the Foot Washing in the narthexes of all three of these churches may reflect the use of this part of the church for a ritual foot washing on Holy Thursday, when abbots imitated Christ by washing the feet of the monks. (Holy Thursday, known as “Maundy Thursday” in the Roman Catholic church, commemorates the Last Supper during Holy Week.)

A monumental image of the heavenly Christ Pantokrator, framed by a rainbow mandorla (an aureole of light surrounding a holy figure) in the central dome, dominates the naos. Photios interprets what must have been a similar image in the Pharos church as Christ reigning from the heavens:

You might say He is overseeing the earth, and devising its orderly arrangement and government, so accurately has the painter been inspired to represent, though only in forms and in colors, the Creator’s care for us. – Photios of Constantinople, Homily 10

Scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin—such as the Annunciation—unfold in the squinches below and throughout the rest of the naos. The eastern apse reveals another Virgin and Child, and additional saints appear throughout the naos.

For worshippers entering these churches, mosaics offered a vision of God reigning from on high, a reminder of salvation history, and face-to-face encounters with so many saints who had come before. No wonder Photios found himself whirling around, trying to take in the overwhelming mosaics at the Pharos church, and feeling as if he had “entered heaven itself.”

Additional resources

Carolyn L. Connor, Saints and Spectacle: Byzantine Mosaics in their Cultural Setting (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Otto Demus, Byzantine Mosaic Decoration: Aspects of Monumental Art in Byzantium (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1947).

Liz James, Mosaics in the Medieval World: From Late antiquity to the Fifteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Henry Maguire, “The Cycle of Images in the Church,” in Heaven on Earth: Art and the Church in Byzantium, edited by Linda Safran (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998), 121-151.

Thomas F. Mathews, “The Sequel to Nicaea II in Byzantine Church Decoration,” Perkins Journal 41.3 (July 1988): 11-21.

Thomas F. Mathews, “The Transformation symbolism in Byzantine architecture and the meaning of the Pantokrator in the dome,” in Church and People in Byzantium: Society for the Promotion of Byzantine Studies, twentieth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, Manchester, 1986, edited by Rosemary Morris, (Birmingham: Center for Byzantine, Ottoman, and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham, 1990), 191-214.

Robert Ousterhout, “Originality in Byzantine Architecture: The Case of Nea Moni,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 51.1 (March 1992): 48-60.

William Tronzo, “Mimesis in Byzantium: Notes toward a History of the Function of the Image,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 25 (spring 1994): 61-76

Nektarkos Zarras, “Narrating the Sacred Story: New Testament Cycles in Middle and Late Byzantine Church Decoration,” in The New Testament in Byzantium, edited by Derek Krueger and Robert S. Nelson (Washington: D.C.; Dumbarton Oaks, 2016).