38

Dr. Nicolette S. Trahoulia

If you visit Venice and walk around the Church of San Marco, you might wonder why the exterior of the church appears to be a mishmash of various pieces of sculpture done in different styles from different periods. The answer lies in the Crusades, and particularly with the Fourth Crusade that began in 1202.

Constantinople and the Crusades

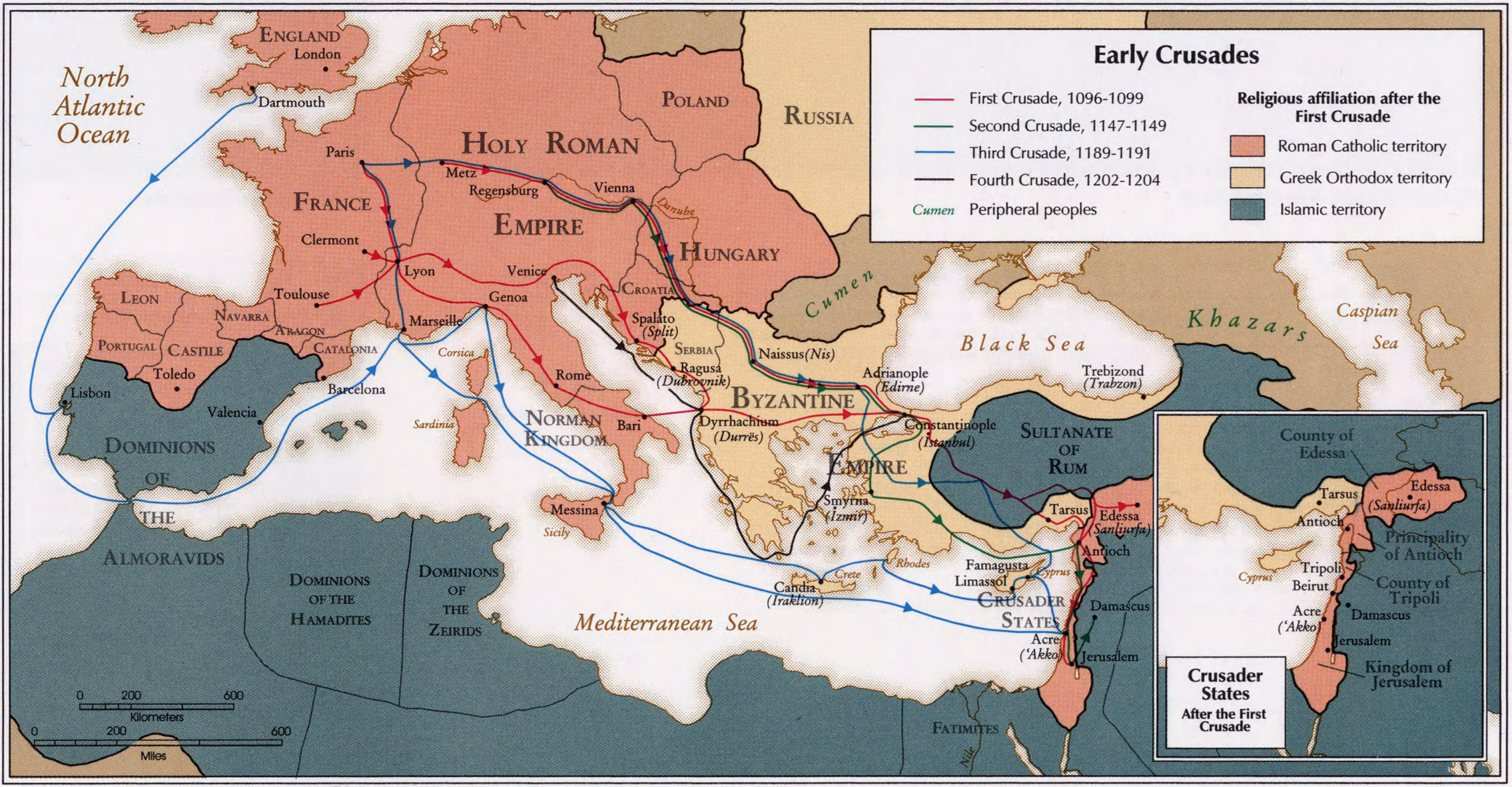

The crusaders were western European fighters, often supported by the pope in Rome, who sought to capture the Holy Land (Palestine) and other regions from Muslims—and sometimes fellow Christians—during the 11th-14th centuries. When the crusaders of the First Crusade arrived in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) in 1096, the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos agreed to help them go through Asia Minor on their way to the Holy Land. But wary of their motivations, he first made them swear allegiance to him. The crusaders went on to conquer Jerusalem from the Arabs in 1099 and established crusader states in Palestine.

In 1203 a fourth expedition of crusaders were on their way to the Holy Land when they were again diverted to Constantinople. Alexios Angelos—the son of deposed emperor Isaac II Angelos —enlisted the help of the crusaders to restore his father to the throne. Although he and his father did manage to rule jointly with the help of the crusaders, they were soon deposed by Alexios V Doukas Mourtzouphlos.

Angered because they did not receive the rewards promised by Alexios Angelos and confronted with the immense riches of what was then the grandest city known to the West, the crusaders attacked and seized Constantinople on April 13, 1204. They would occupy the city until 1261 when Michael VIII Palaiologos reclaimed the city for the Byzantines.

Looting Byzantium

During the almost sixty years of occupation by the crusaders (or “Latins,” as the Byzantines often referred to western Europeans during this period), Constantinople was looted of countless artworks. Many of these impressive artworks are now in museums and churches all over Europe. Venice, which provided the ships for the Fourth Crusade, possesses much of the art that was taken by the crusaders, such as the life-size gilt bronze horses that were displayed on the exterior of the Basilica of San Marco. These horses were attributed to the famous sculptor Lysippos who worked in the fourth century B.C.E., although they may have been made later.

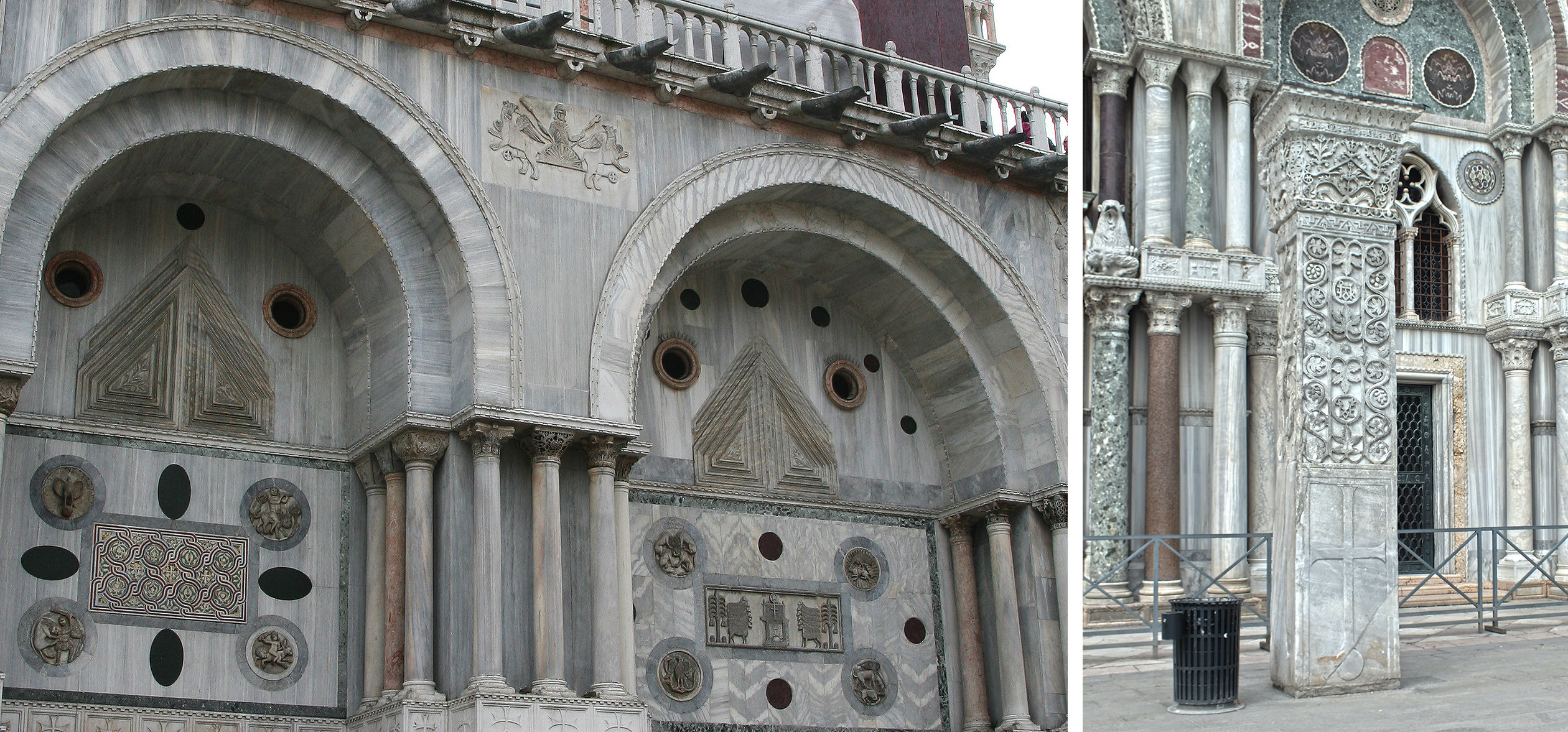

Another example of looted art is the porphyry statues of the Tetrarchs (four Roman emperors), now built into the side of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice. The missing foot of one of the Tetrarchs was found in Constantinople, confirming that this sculptural group was originally set up somewhere in the Byzantine capital. These statues represent a short-lived system of rule during the late Roman Empire when the emperor Diocletian was trying to stabilize political authority in a time of crisis by sharing rule among four emperors.

Numerous marble reliefs on the exterior of San Marco have been assigned a Byzantine provenance, such as the eleventh-century relief of Alexander the Great ascending in a chariot raised by griffins. This popular image of Alexander derived from the legendary Alexander Romance (an account of the life and exploits of Alexander the Great) in which we read of Alexander’s bold attempt to explore the heavens in a chariot pulled by winged griffins.

Ornate carved piers (known as the Pilastri Acritani) taken from the Church of St. Polyeuktos in Constantinople stand near the south-west corner of San Marco. The grand Church of St. Polyeuktos was built in the 520s by the Byzantine aristocrat Anicia Juliana and its beauty and size rivaled that of the Church of Hagia Sophia (also referred to as “the Great Church” by the Byzantines) in Constantinople.

Sacred spoils

The Treasury of San Marco is full of rich objects that must originally have come from Constantinople (see above). Many fine examples of Byzantine metalwork and enamels are housed in the Treasury, such as the gilt-sliver incense burner in the form of a multi-domed structure that possibly represents a garden pavilion. The incense burner is decorated with female personifications on the exterior and mythological beasts, such as griffins. Another such object is a eucharistic chalice made of a Late Antique onyx bowl set within a gilt silver frame and decorated with a series of enamels. The inscription on the chalice reads “God help Romanos, the Orthodox Emperor,” referring to either the emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (920-44) or Romanos II (959-63).

Constantinople reclaimed

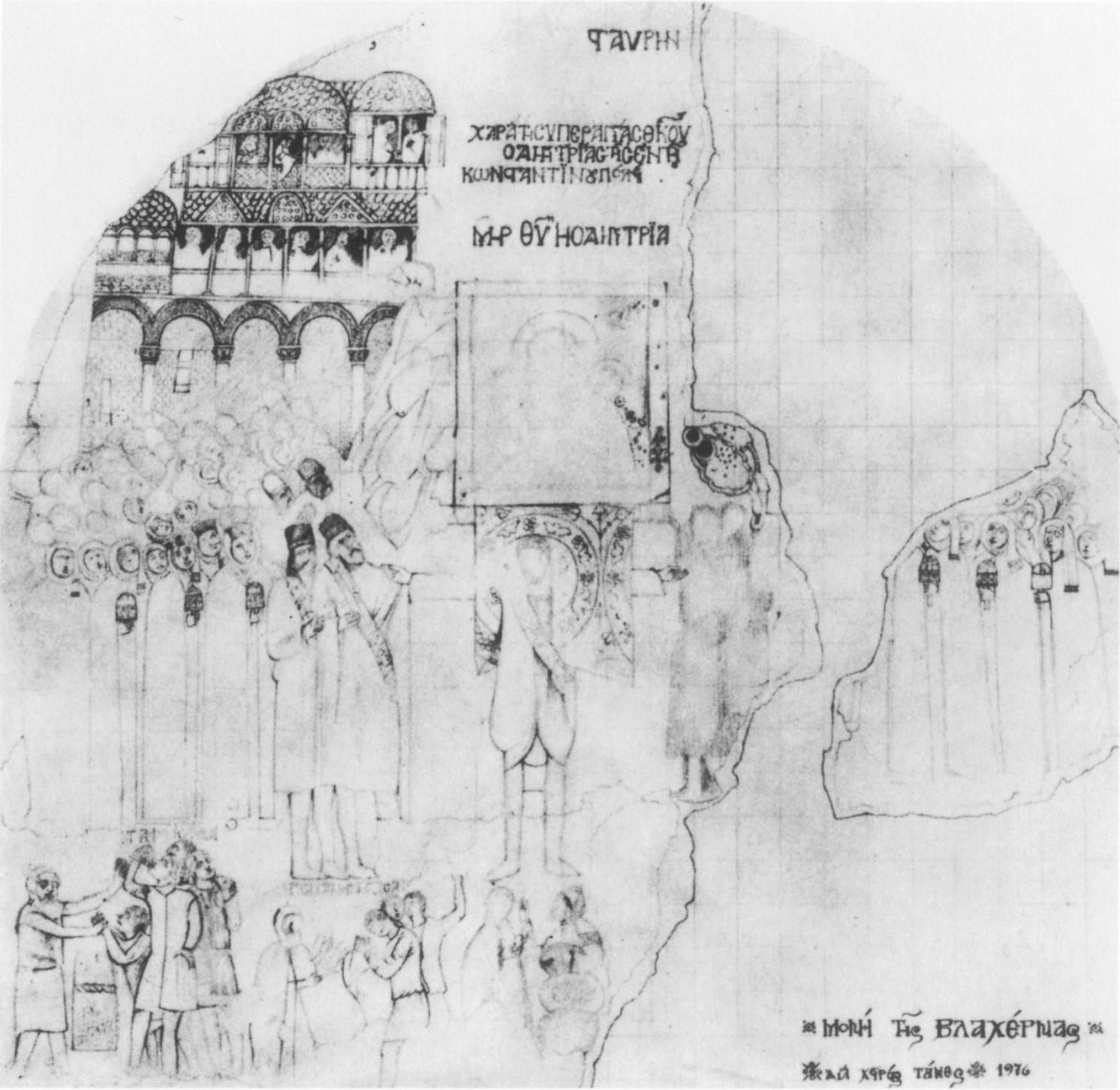

During the period of Constantinople’s occupation by the crusaders, there were three Byzantine successor states, the Despotate of Epirus founded by Michael Komnenos Doukas (with Arta as its capital), the Empire of Nicaea founded by the Laskarid Dynasty, and the Empire of Trebizond founded by Alexios Komnenos. It would be the Nicaeans who would later recapture Constantinople in 1261. In the Despotate of Epirus, the Monastery of the Panaghia of Blachernae north of Arta contains a three-aisled basilica built in the 13th c. with a wall painting of the procession of the famous icon of the Virgin housed in the Church of the Blachernae in Constantinople. The mural recreates the great city of Constantinople for the empire in exile.

Soon after the city was reconquered in 1261, a mosaic was put up in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia. Only the upper part survives today, but the figures were originally over twice life-size. Christ is represented in the center, flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, a grouping called the Deësis. The mosaic was probably part of Michael VIII’s major campaign to restore and renew Hagia Sophia after the alterations made by the crusaders. Perhaps the mosaic was intended to celebrate the triumph of the Byzantines over the crusaders. The Deësis as a subject refers to the intercession of the Virgin and John with Christ on behalf of humankind. The mosaic may have stood as a kind of visual prayer to insure the city would never be taken again.

Additional Resources

<http://www.meravigliedivenezia.it/en/index.html>

David Buckton, ed., The Treasury of San Marco, Venice (Milan: Olivetti, 1984)

Henry Maguire and Robert S. Nelson, San Marco, Byzantium, and the Myths of Venice (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2010)