8

Dr. Anne McClanan

A monastery built on holy ground

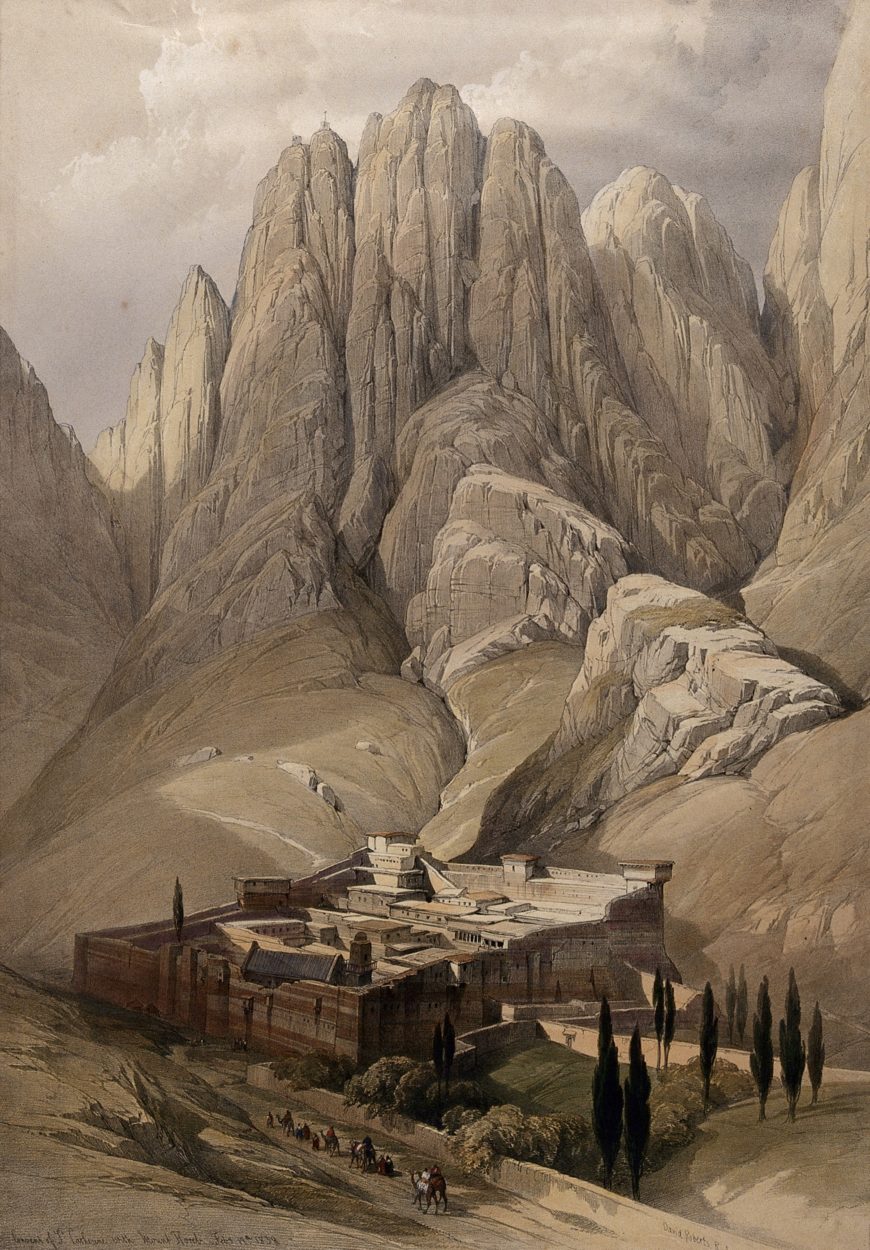

The Monastery of Saint Catherine is the oldest active Eastern Orthodox monastery in the world, renowned for its extraordinary holdings of Byzantine art. (The Orthodox Church is the second largest Christian community after the Roman Catholic Church; Christianity split between Orthodoxy in the East and Roman Catholicism in the West in 1054, known as the Great Schism.)

The location of the monastery is significant for Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, because tradition identifies it as the place of the Burning Bush, a major biblical event where Moses encountered God:

Moses was keeping the flock of his father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed. Then Moses said, “I must turn aside and look at this great sight, and see why the bush is not burned up.” When the Lord saw that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, “Moses, Moses!” And he said, “Here I am.” Then he said, “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” He said further, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.” And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God. – Exodus 3:1–6 (NRSV)

The episode is represented in several artworks in the monastery’s collection, including an early thirteenth-century icon (Greek for “image”) made of tempera and gold on wood. This image represents the moment when God spoke to Moses: “Come no closer! Remove the sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground” (Exodus 3:5, NRSV).The Monastery of Saint Catherine was founded between 548–65 C.E., in the later years of the Byzantine emperor Justinian’s reign, part of a massive building program that he had initiated across the empire.

The basilica

The monastery’s exterior walls and main church, which pilgrims can still see today, largely survive from the original, sixth-century phase of construction. A few elements came later (for example, the belfry was added in the 19th century).

Transfiguration mosaic

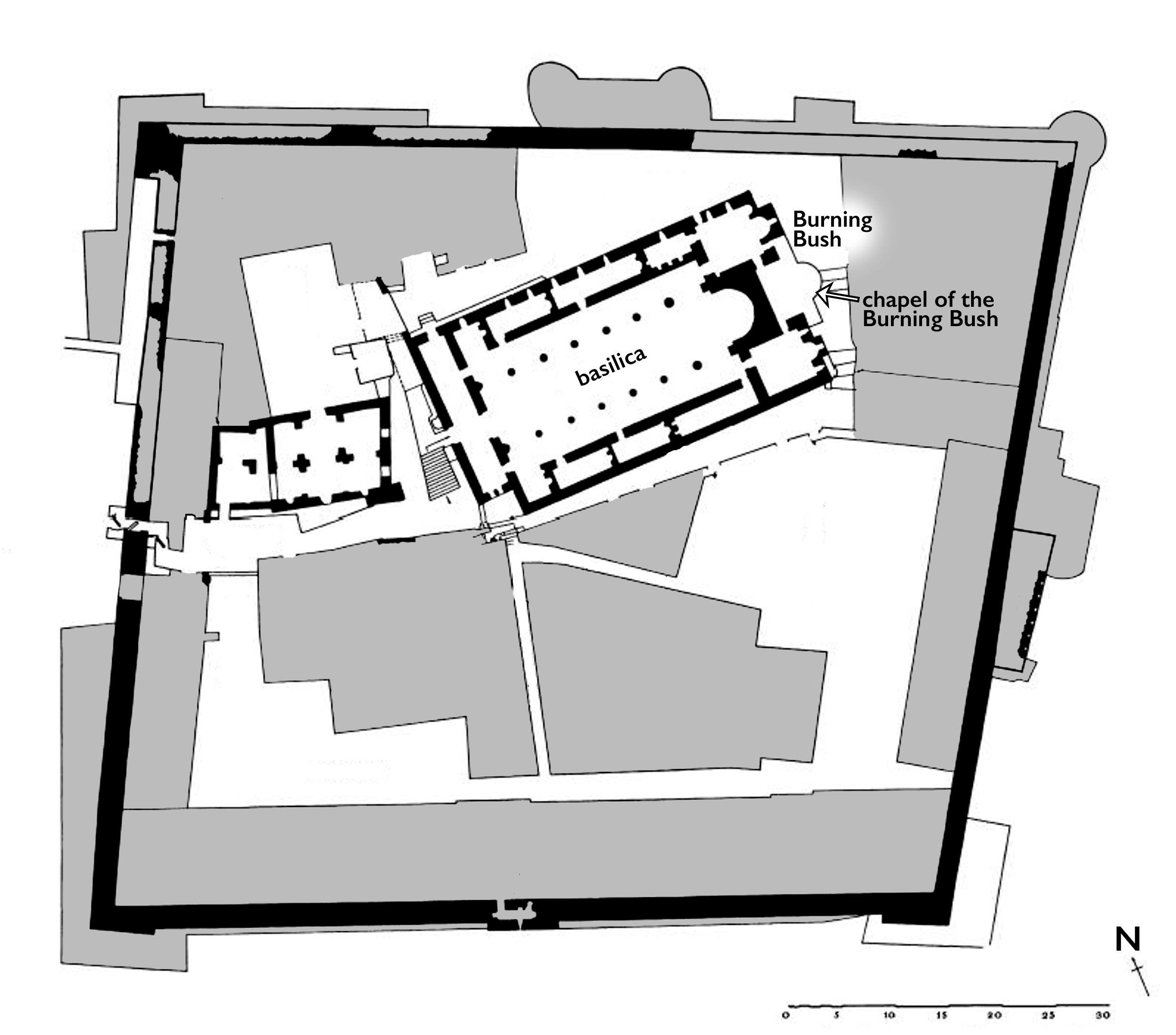

The church follows the pattern of a basilica, having a rectangular plan. Monks have worshipped for 1,400 years inside this church.

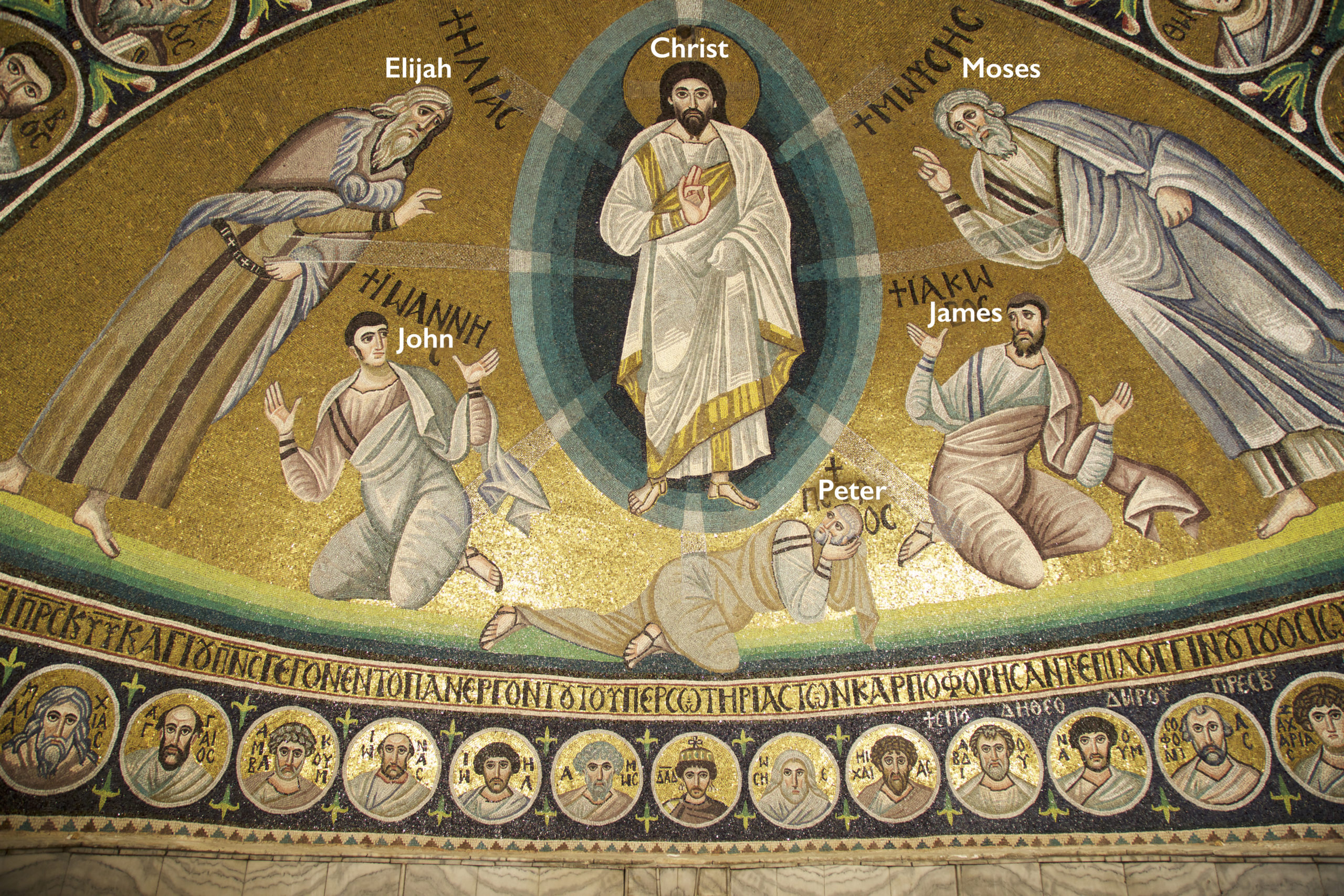

Columns frame the central nave and above the altar is a recently-restored apse (a semicircular recess, usually terminating the longitudinal axis of a church, containing the altar) mosaic that might hint at the building’s original name. The mosaic depicts a moment in the Christian New Testament called the “Transfiguration,” in which Christ appears transformed by radiant light, an event witnessed by three of his apostles. The scene is set against a glimmering gold background. When the monastery was first built it might have been dedicated to the Transfiguration, which in Christian belief is like the Burning Bush in that it is a moment when God revealed himself to humanity.

Jesus took with him Peter and James and his brother John and led them up a high mountain, by themselves. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his clothes became dazzling white. Suddenly there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him…While he was still speaking, suddenly a bright cloud overshadowed them, and from the cloud a voice said, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell to the ground and were overcome by fear. – Matthew 17:1–3, 5–6 (NRSV)

Renaming

Later, in the 9th century, when the body of the revered Egyptian Saint Catherine of Alexandria was discovered, the monastery was given the name that it has kept until today.

Icons and Iconoclasm

During the Iconoclastic period of the eighth to ninth centuries, the Byzantine Empire, and particularly its capital city of Constantinople (modern Istanbul), was convulsed with the question of whether religious images with human figures (called “icons”) were appropriate, or whether such images were in effect idols, akin to the statues of gods in ancient Greece and Rome. In other words, did worshippers pray throughicons to the holy figure represented, or did they pray to the physical image itself? The Iconoclasts (those who opposed images) attempted to ban icons and reportedly even destroyed some.

But by the time of the Iconoclastic controversy, the Sinai Peninsula, where Saint Catherine’s Monastery is located, was under Islamic rather than Byzantine control, enabling the monastery’s icons to escape Iconoclasm. Other factors, including the monastery’s isolated location, fortifications, continuous occupation by monks, as well as the dry climate of the region, all likely contributed to the preservation of icons at Sinai.

Early Byzantine Icons

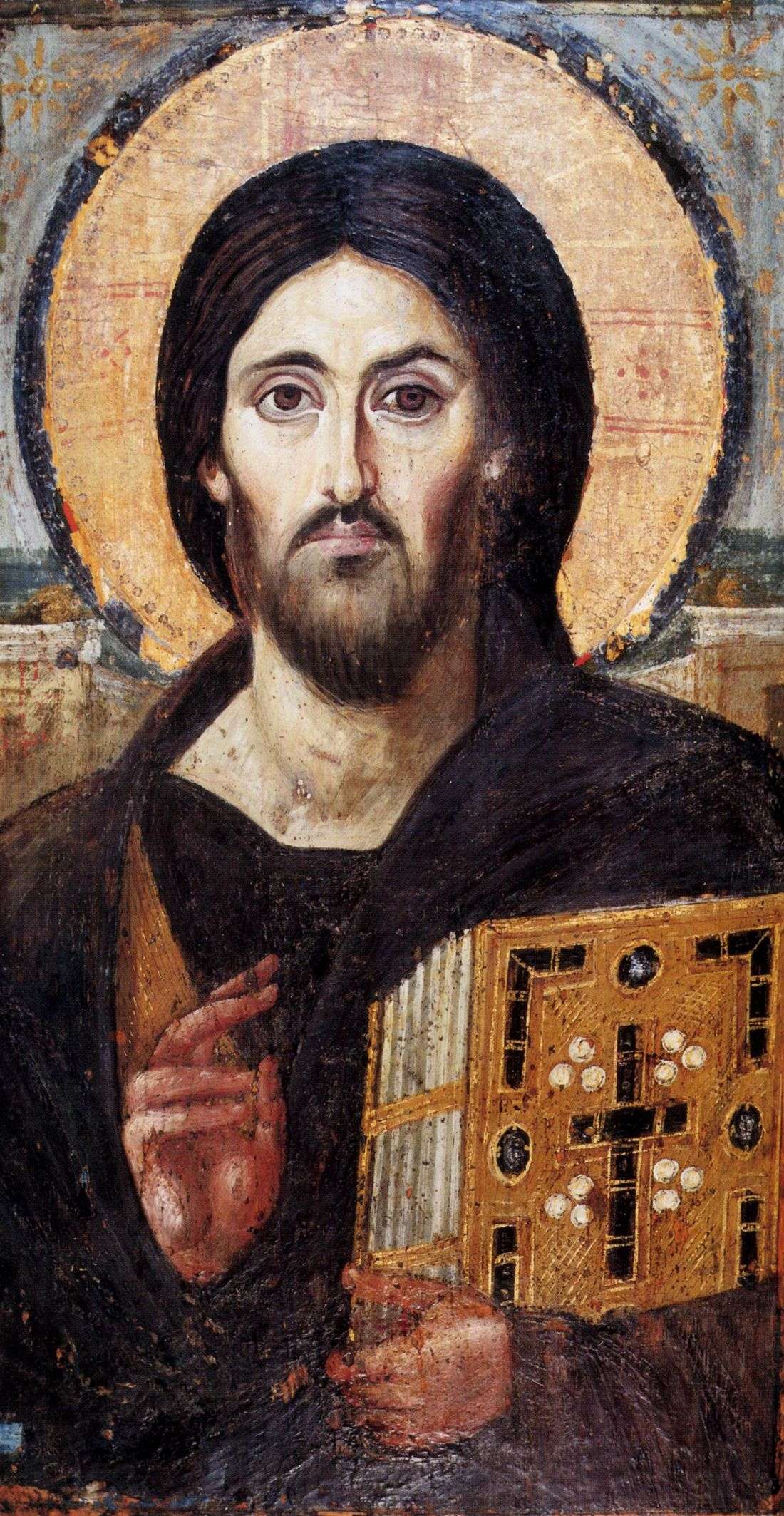

The sixth-century icon of Christ Blessing—or Christ “Pantokrator” (all-ruler), as this image would later become known—was painted using encaustic (a wax-based technique used in Egypt from at least the late 1st century C.E.) that enabled the artist to create a vivid sense of naturalism. This icon was painted by a highly skilled artist, and therefore might have been made in the capital city of Constantinople.

Christ raises his right hand to give a blessing. His other hand holds an elaborate manuscript, which probably takes the form of a contemporary Gospel book, emphasizing Christ’s identity as the embodied “Word” of God. This bearded, mature version of Christ—just one of several ways Christ appears in art before Iconoclasm—draws on pre-Christian traditions of rendering other male divinities such as Jupiter. The Monastery of Saint Catherine preserves a number of rare Early Byzantine icons such as this.

Middle Byzantine Icons

After Iconoclasm, perhaps to avoid accusations of idolatry, Byzantine icons became less naturalistic. Compare this Middle Byzantine icon of the Heavenly Ladder with the Early Byzantine icon of Christ. Notice, for example, the ethereal, flat gold background in the icon of the Ladder that replaces the landscape hinted at behind the halo in the sixth-century Christ “Pantokrator.”

The Heavenly Ladder

This icon of the Heavenly Ladder was made at the monastery of Saint Catherine in the late 12th century, and illustrates the process of spiritual ascent undertaken by monastics (the term “monastic” refers to monks or nuns). The icon is based on a spiritual text of the same name, written by a monk called Saint John of the Ladder, who lived c. 579–649 and was a member of Saint Catherine’s Monastery. In his writing, John warns his fellow monks about temptations of the monastic life; in the icon of the Ladder, the artist depicts these temptations as elegantly silhouetted demons who attempt to tug the monks off the ladder as they climb toward Christ in the upper righthand corner.

Saint Theodosia

This 13th-century icon depicts Saint Theodosia and is one of five icons at Saint Catherine’s that depict the same saint. Clearly, Saint Theodosia’s cult was popular at Sinai as it was elsewhere in the Byzantine world.

In this image, Theodosia wears the somber dress of a nun. Although her historical status is debated (she may have been legendary rather than an actual historical figure), to the Christian faithful she represents the challenges faced during Iconoclasm, when she reputedly died defending a famed icon of Christ in Constantinople. The cross she holds represents her martyrdom. She was also famous in the late Byzantine period for healing miracles attributed to her, further enhancing her appeal for worshippers.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery today

The library of this centuries-old monastery houses many important medieval manuscripts in diverse languages such as Greek, Arabic, and Syriac. It continues to attract pilgrims from around the world—some of the current monks now in residence hail from exotic lands such as Texas.

Additional Resources

Robert S. Nelson and Kirsten M. Collins, eds., Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006).